Reflecting on Garth Greenwell’s Cleanness (2020) New York, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. Page references are to this edition.

This novel is welcome and important to every reader because of its take on what it means to write on and about relationships, including those between storytellers and hearers, storywriters and readers. Indeed, I think the very structure of the novel, posing as it does as a set of discrete stories wherein the links and relationships between those single story-based chapters are not always clear, is about patterns in made, unmade, completed and incomplete relationships.

We will only link the stories that form into Cleanness by acts of completion of doubtful authority by each ‘mere’ reader. Acts of completion will, in that event, almost certainly say as much about us as readers and/or persons as about Greenwell’s narrator, who is himself a kind of doppelganger of the author, rather than the author themselves.

I want to start by looking at how the story set might prompt means of looking at it as a whole, with a development within it that could be aligned with a novel’s ‘plot’. However, in order to do so I could only see that structure as a kind of cycle of explorations of a more or less continuous narrator and significant others. Its central part (Part 2 in the three-part overall structure) examines one key relationship with a character named R. At either end of the novel the parts each consider relationships much more around features of social and / or sexual role-play. All have some relationship to how and why power is articulated in relationships – which is always complexly.

I sense that Parts 1 and 3 of the novel divide their sub-section stories / chapters around three ‘memes’ in the understanding of relationships: the pedagogical, the sadomasochistic and issues of social identification. I don’t feel that these ‘memes’ have anything but fuzzy boundaries. Indeed the whole effect is that of seepage between them.

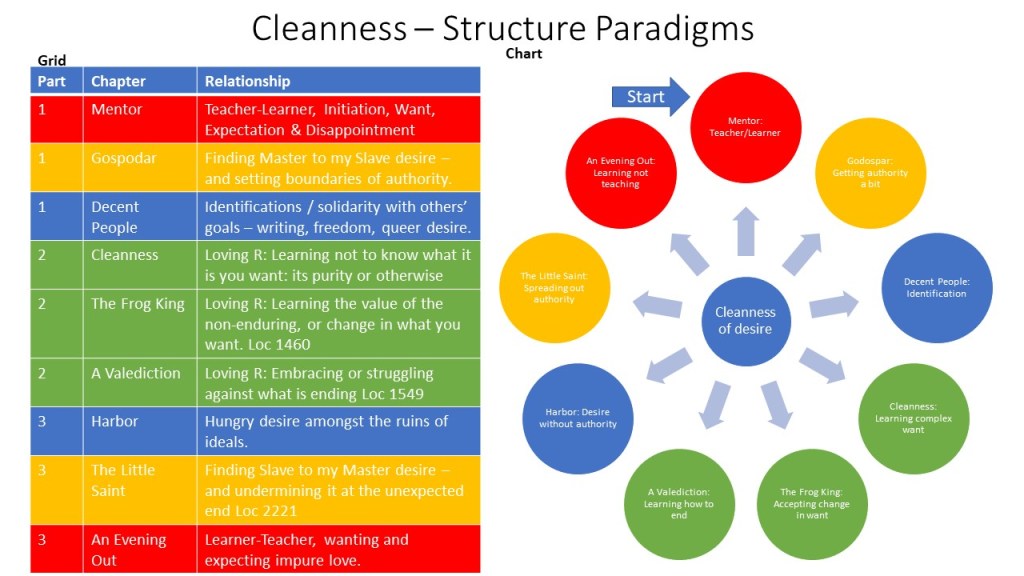

Moreover, my titles for these memes remain very provisional whilst claiming some initial appeal. I found it helpful to map the structure of the novel as a grid based from its internal story-chapters and then as a cyclical chart. During this exercise I thought I discerned a relational circularity in its themes and memes, all ultimately circling on issues of desire for the ‘other’ and the problems of defining that other. At this point I sense that the queer project herein is to both state and deconstruct simultaneously any simple, clean or uncluttered sense of the ‘other’ implied by our primal desire.

This chart (above) makes many assumptions and it is not my aim to discuss these here. They pose questions to me as a reader at a provisional stage of my reading, although I am already aware that my reading, however repeated and continued and handled, will remain provisional. That, perhaps, is what the novel might, in some way, demand.

However, it’s clear to me as I read that ‘relationships’ are what the stories tell us about (in the sense of creating both a discourse, structure and construct of ‘relationships). It assumes that ‘relationship formation, maintenance and ending’ is bound up with storytelling and listening. I prefer the term storytelling to the more forensic term, narrative, since it is this performative act of telling a story that is our entry to relationships in almost every way we could try to make this entry.

Stories are at the base of every interaction in the novel, even that between narrator and reader. The story-chapters contain in themselves various stories the in which characters build ‘mutual’ relationships. Even if we prefer a less generalised notion of how people perform their mutual relationship over its duration, storytelling certainly acts to characterise, confirm or deny a relationship’s validity and structurally also acts to initiate and end them.

So often, in this novel, people tell each other stories. The opening story ‘Mentor’ can be interpreted as about how an older man with authority over a younger, a kind of pedagogue from the Greek tradition, uses his own life-set of relationship-stories in order to instruct and refine the naïve and simpler stories of the young student. In the chapter, the student is G. Yet it remains unclear in the chapter how much of those stories G. desires to hear and does in fact hear from the narrator (let’s call him for convenience GG without asserting any identification of narrator to author). The relationship of GG and G ends by ending the telling of a story being told within it:

He raised his hand then, signalling for the waitress and signalling too that our talk was over, that he had exhausted all hope of my helpfulness; and I was both relieved and exasperated by this, and exasperated too by what he had said. But this is a story you’re telling yourself, I said, a story you’ve made up that will make you unhappy. There’s nothing inevitable about it, it’s a choice you’ve made, you can choose a different story. But he was already gone, …

Greenwell (2020:21f.)

The construction of sentences here, even the wilful innovation of the use of punctuation, is I believe about the turning of language into a story-like performance. Others have concentrated on the se of semi-colons, but many have pointed out the radical effect of not using, at any point, speech-marks. The effect, of course is to blur the difference between reported and direct speech, the spoken or unspoken, heard and unheard stories.

This can happen in very subtle ways, even in the micro-construction of a story at the level of a sentence. For instance, earlier in the chapter, the narrator reports a story that G tells him about G’s relationship with B, in which (bear with me as I try to describe continual reflexive storytelling about storytelling) B is telling him stories. At this point G has just been told the story of B’s romantic or sexual liaison with another boy (ibid:16):

… And he said all this to me like I knew it already, G went on, like it was so clear it didn’t need to be said. But I didn’t know, I hadn’t seen anything, and as I sat there I felt something I had never felt before, it was like I was falling into something, like water though it wasn’t really like water, it was like a new element, G said. But surely he didn’t say precisely that, surely this is something I’ve added; added in solidarity, I’d like to say, but it wasn’t solidarity I felt as I listened to him, it was more like the laying of a claim. The experience he had was my own, I felt, I recognized it exactly, and as he spoke I felt myself falling also, into his story and his feeling both, I was trapped in what he told.

ibid:16

The absence of punctuation for reported speech marks Greenwell’s decision to avoid the clarification such punctuation gives as to who is currently speaking, who listening and of the turn-taking all dialogue involves. Hence even the uses of frequent markers like ‘he said’ often come too late to obscure the sense that the ‘I’ in this story could be either G or GG. Reported speech then, by virtue of this alone, necessarily embeds stories within stories in which stories are also embedded and which the agency of speech is made difficult to attribute.

In this beautiful passage this effect is conveyed by the metaphor of ‘falling into’ something. Moreover the narrator suddenly reveals that the effect of reported speech is anyway illusory, containing new elements of which the reported speaker could have been oblivious –‘something I’ve added’. Whether that new element is ‘water’, for want of a better metaphor, or ‘his story and his feeling both’, its nature is fluid, its content often sticky – adhering to the surfaces of the bodies from which it is emitted.

That isn’t always the case with stories. In fact it is only in Bulgaria that the narrator feels deprived of the power of the stories that might interpret a culture of stories that are not his own. In the central relationship-story, with R, GG takes control of the contexts of his story-telling more and more. This is symbolised in a visit to the European West. Taking R to Venice facilitates his control of the interaction between the two with stories over which he, Gospodar,[1] has apparent authority.

In churches in Bulgaria the paintings were more or less mute to me, but here they made a story I could read, and as I told it to him I saw the pleasure R. took in it, the way he looked at me and then at the painting, I loved to see it.

ibid:124

When the narrator takes authoritative control over the culture, he does the same with the relationship, guiding it. Like a supreme pedagogue, he glories in the reflexive ‘I’ that comes to dominate the sentence as it ends. GG sees himself alone reflected in the direction-making in that relationship.

Such moments also guide the mutuality of combined bodies. For instance, R’s expressed desire in relation to GG moulds itself within the same paragraph-long subsection quoted above into this:

Tell me a story, he said, as I lay beside him, running my hands across his chest and stomach, feeling his cock grow thick when I grabbed it, tell me another story.

ibid:125

The sex which follows animates a play of bodies inspired by whoever has control of the sexual narrative through the performed moments of passivity, motivated action and resistance that constitutes sexuality here: ‘alternating precaution and risk’ (ibid:190). These passages will tell us how to read the two sadomasochistic stories in the book – the first in which he loans the Gospodar role to someone else, the second, the penultimate chapter, where he plays it for himself, and which leads to an unexpected ending. In that ending, the ‘little saint’s’ passivity begins to rule the genesis of stories rather than active authority. It is the passive sexual partner in that chapter who actively ends the story of this sexual contact in a surprising way:

…, and I realized that I had been wrong before; it did have an end, what I had felt, its end was here, he had brought me here. … Do you see? You don’t have to be like that, he said. You can be like this.

ibid:195f.

Of course sex never quite conclusively distributes the roles internal to it of authority and submission as much as might be intended by one or other partner. The greatness of the book is that it recognises that truth, because neither really do the performance of telling and listening to stories. Sometimes listeners and readers take control.

Sometimes too the stories resonate with André Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name which also investigates how storytelling, sex and inequality of experience and age interact with each other. This is surely part of the play around the sharing and their function in commanding, prolonging or inhibiting action that is caused by using the name Skups that GG ‘shares’ with R. Each applies it to the other but not always for the same purpose.

For couples sex is an adventure, and perhaps also for sex where more than two participate, where extension of the field of experience is only mutual by acts of collaborative performance beyond boundaries accepted at a present moment. Hence the long passage of sex in ‘The Frog Prince’ between GG and R has to move in steps where neither is sure of what either the other will allow or what they themselves want or desire.

The decisions are described as if analogous to artistic ones, in that each artist in the sexual bond holds a more or less restricted ‘palette’ of performance as they ‘draw lines’ for each other’s performance. GG at one moment, still unsure of what he wants to make of the passage of bodily contact. It is by naming themselves, the other or each other, tentatively or assertively depending on urgency, that resistance to further adventure is potentially adverted or the existence of a resistance to be negotiated is also ‘named’:

But I wasn’t sure what I wanted, or what I wanted had changed. I had thought I wanted to make him laugh. that after that I wanted sex, but I didn’t want sex, I realized, or not only sex. … It had been a line drawn early on, when it became clear I was more adventurous in sex, had a wider palette of things that turned me on; I hope you are not into that, he had said, laughing, it’s gross, … Skups, R. said, a question in the way he said it, his name for me or our name for each other. But I didn’t answer, … and I would do it even though I could feel R.’s impatience, even as he said again Skupi, and then don’t be cheesy, which was his warning against too much affection, against my surfeit of feeling.

ibid:pp.128f. My omissions, author’s italics.

This is beautiful and it is subtle. It is about how mutuality is negotiated, not only between lovers, but also between the adventurer in a field and their companions. It tests for danger areas, negotiates resistance whilst building it further into the adventure. What is also clear is that negotiation allows even the supposed leader in the adventure to refine their own performance of a desire so unnamed, it may yet be unknown. We see in the passage the process of how ‘what I wanted had changed.’

In such a reflexive novel, it is certain that the negotiations in sex describe in some ways its own process of art as storytelling, a thing often discussed in terms of visual or audible art by GG. In these passages art might seek cleanness, purity and perfection of form or content. I do not know to what extent the terms cleanness and purity (both central in the novel themes and used of sex and art) are synonymous but I expect they are not making it that easy for pattern-seers like myself. Describing the art in a museum visited by R. an GG, the latter says:

… the whole painting was eccentric, asymmetrical. … I liked the seeming naivety of it, the way the simple figures had been simplified further, purified or idealized to geometrical forms, almost, but rendered bluntly, imperfectly. And the brushstrokes were imperfect too, visible, haphazard, the paint distributed unevenly, inexpertly; but that wasn’t right, really it was striving for something ideal. that was what I felt, the frequency I wanted to catch. …

Ibid:119 my omissions

The passage should be quoted without omissions and at greater length, as it continues from where I leave off by constantly again querying its own adequacy and perfection of expression. It, like the painting described (one which may not exist), performs the continual aspiration for perfection by exploring its opposite – the incomplete and imperfection. It throws up the possibility of purity but finds it only in the less pure existence of materials artist and lovers use in striving for that unrealised end.

In that sense, art matches sex, and, for my purposes, what the art of this novel has to say about relationships. For the novelist, this means an art that exerts its authority towards the achievement of fullness and wholeness but which continually falls short of that end. Indeed, we begin to suspect art, sex and relationships must always fall thus short if their raw materials are to be empowered too. And the novelist’s raw materials are not only his character’s, his own persona GG included, but anyone who intrude into and take authority from GG to show that they will not be, cannot be merely moulded by authority. Of such is made the reader – never ideal.

In my view that goes for the narrator and author’s different relationships to the reader too. And that, in part is about allowing one’s art to be a little dirty, stained and impurely unclean. In effect GG only learns this when he puts aside Western views of art and perhaps accepts the failure of other Western ideals, long since contradicted in his practice, like the purity of monogamous desire and possession that haunts Part 2 of the novel.

I see this in this passage where GG’s hand is made unclean and performatively cleaned on his jeans by breaking through a taboo on touching ancient stone-art in the Doctor’s Garden adjoining Sofia’s University.

He does it at the urging of a student for whose body he clearly lusts:

… I said something about its antiquity, how it was thousands of years old and he was using it as his table. … We have stuff like this everywhere, he said, if we didn’t touch it we couldn’t live. And besides, Z. said, don’t you think it’s better out here than in a museum. I think it likes it, and he ran his hand down the length of the stone, a strangely sensual gesture. I think it likes us to touch it. Go ahead, he said, you touch it too, and when I hesitated, he took my arm just above the wrist and pulled it to the stone, I laughed, surrendering, and stroked it as he had done, the stone warmer the air, it must have been soaked in the late sun, and pocked, not smooth at all, or smooth only where the letters have been chiselled into it, the slanted edges of the cut still perfectly polished. I drew my hands away and wiped them on my jeans. …

ibid:203f.

He learns that art is not dirtied by aiming to be liked by any means it might use: be it even the touch of a sensual, even a pornographic, hand. This passage plays out the same game of the adventuring transgressive hand – through wonderfully transgressive sentences – that perform playfully in sex and the making and the feeling of great art. Feeling is very important.

If your listener or reader fails to feel anything, even the shudder of transgressive sexual desire as they read; then a speaker, actor or writer fails to relate to a listener or a reader. Hence play continues through resistance and adventure, even where, in this last chapter desire gets lost in the resistance that ought to lead it on.

For instance read again the scene in the urinals of the club where GG tries to read Z’s face, eyes and general performance before and after Z ‘tucked himself away and drew up his fly,’ (ibid:213) Perhaps this can only work on a male queer audience – one would like to know since, as the whole chapter points out, the meaning of Z’s playfulness is never discovered. We never know, for instance how Z, having invited GG to punch his torso and grip his hard muscle, reads the following performance, although how we, as readers, read it may tell us much of ourselves that defies norms.

Then I released my grip and smiled and brushed his stomach quickly up and down with the back of my hand, as if to erase the trace of how I had touched him.

ibid:210

Being touched in this novel is about an imagined sense perception but also about how art performs ’emotion’. This performance may make what we are touched with feel transgressive. We may want to wipe from our hands, and the eyes of our imagination or memory, what we collect from it. I found it difficult for instance to read Chapter 2 for reasons I can’t altogether pin down but the sense of wanting to reject the book at that point, and not to deal with it here, stays with me.

Of the comment on many books there is no end, and this is a case in point. This is a measure of its greatness because no commentary will comprehend much beyond the cognition at its surface. So much depends on what you imagine yourself to feel sensuously and as result of it musical resonances and rhythms.

But I can’t leave it without saying how important is its project to reform how words that name ideals, like purity, cleanness, perfection, are used. Let’s take one that puzzled me long. I found it difficult to know the significance of Chapter 3 Decent People, of Part 1. Yet all least part of its effect is to align GG more with the LGBTQI+ people he meets accidentally as part of a rally in Sofia’s streets.

Drawn initially to university colleagues and debate, he sees that this group has been attacked by other non-queer protesters. This leads him to further identify with them; not least because he must redeem them (by virtue of association with him since this chapter swims in the same sea as Whitman’s Song of Myself which appears in it) by feeling that alliance of identity as deeply as he can.

Some assholes showed up, she said, some of those assholes in masks, they grabbed our signs from us, and they hit S., … Indecent, K. said then, they said we were indecent, they called us dirty queers. …

ibid:81

A novelist could not have marked the import of this passage more than by the title given to the whole chapter, Decent People. Likewise I’m certain that it faces up to the language that calls what it hates by the name of uncleanness, impurity and dirt. What is decent is what some people call indecent. What is clean what some people call dirty. Of course these simple reversals are much more nuanced in dealing with other themes but the terms of debate may stay constant even though their outcomes are so very mixed and inconstant.

So defeated and tired in my opening aims, I’m retiring from this blog. Do enjoy the book. I will return to the book over and over again. Perhaps next time on the publication of the edition in the UK.

Steve

[1] https://glosbe.com/bg/en/gospodar gives this as a masculine noun in Bulgarian meaning ‘lord’ or ‘master’. Used of teacherly authority, perhaps ironically.

9 thoughts on “Reflecting on Garth Greenwell’s ‘Cleanness’ (2020) New York, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.”