Reflecting on Exhibition on Screen: David Bickerstaff’s film of Lucian Freud: A Self-Portrait (at Royal Academy of Arts, London) seen at Gala Theatre, Durham, Screen 1.

Some further related thoughts in: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2020/02/02/reflecting-on-the-dual-concepts-of-influence-and-reference-in-art-about-art-using-one-case-study-raised-in-david-bickerstaffs-film-of-lucian-freud-a-self-portrait/

I came out of this film presentation absolutely delighted – this was not only a great source of information but a work of art in itself – bookended by archive film of Freud saying to camera that he ‘wanted to shock and amaze.’

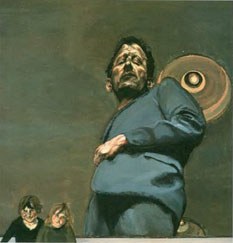

Bickerstaff faces that challenge head on and shows the material out of which the shocking and amazing was made. If the filmmaker certainly amazes his audience, what is most shocking in Freud spoke through the paintings and not their biographical contexts which were rarely given but only hinted at. It is not only shocking but almost painful to look for long, for instance, upon Reflection with Two Children (1965).

It is not only that these otherwise unnamed children are Freud’s children but that the painting not only marginalises them but paints them in a separate world, as opined in the film itself. We are told no more of the difficult biographical material that could, that might, underlie such a perception. This is correct.

The picture is too easily otherwise stereotyped.

Of course it is in an important sense about power and powerlessness. Freud’s look may be trying to objectify what he is seeing but he is also removing himself from all relationship and understanding which surrounds our concept of the normatively human. It emphasises his relationship to the lighting above him rather than to ‘his’ children.

Giving more of the highly available biography, since after all his biographer William Feaver, is one of the experts here, might have tipped shock into titillation, the strangeness of the issue of relational identity between self and other (since the other is also what a ‘reflection’ is) into art historical and society-paper gossip. As a result too some important relationships aren’t covered, such as that with Celia Paul, even though the contemporary nude self-portrait, Painter Working, Reflection (1993), is discussed at some length.

Moreover, speculation about Freud’s sexuality is about acceptably normative, if laddish, forms and hence fails to illuminate the, for me, vital concern with omnipresence of signs of male sexual attractiveness and repulsion in his male portraits, and self-portraits, that is as strong as those in same features in female portraits and ‘skins’.

Although I think I may over-stress this myself, as in this blog, I think the constancy of queer men in his entourage throughout his life, from Cedric Morris and his ‘boyfriend’, as Freud describes the extremely bisexual hunger that is Letts-Haines. Hence Peter Watson, Stephen Spender (whose love for Freud was an open secret), John Craxton, John Minton and even Francis Bacon become desexualised or merely presented as camp, or in Spender’s case not mentioned at all.

Yet the painting by Francis Bacon of two classical wrestlers which Freud renamed ‘The Buggers’ (the term used by the Bloomsbury Group, including Virginia Woolf, for gay men) was one painting he never sold in his lifetime.

Queer life of the 1940s onwards, right up to ten years after the passage of the 1967 law decriminalising homosexuality in private, is not so easily characterised in terms of sharp boundaries of sexual types, whatever the contemporary psycho-sexology was saying. One of the means Freud evaded military service was to assert that he was so attractive to other men, he would need a single room to deflect the ardour of squaddies (you’ll have to read Feaver yourself for that).

But I need to get back on track by saying again that detail of his ‘shocking autobiography’, whether it concerned the loose morality of the upper classes into which he easily slipped or the purchasable working-class boys he befriended and painted, and sometimes slept with ‘when drunk’ according to Bacon, all of his life, is less relevant the shock of attempting to see what his paintings truly convey.

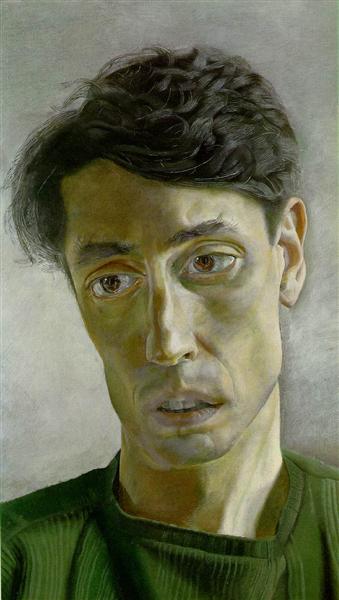

It is a painting of shocking perspectival tricks that fragment vision or make it an indirect take on action. These tricks often fragment persons, even his own ‘reflection’ (all he ever painted in painting self) as in the haunting Interior with Hand-Mirror (Self-Portrait) (1967) and Interior with Plant, Reflection Listening (1967-8). These works go as far as it is possible to go to draw meta-generic lessons from both still-life and portraiture.

The experts consulted in this film all illuminate and are those people already deeply associated with Freud scholarship – Feaver (of course) but also artist-model-friend-critic, David Dawson, Sebastian Smee and artists who carry his tradition on into new realms, including in feminism guided by female artists (who were – perhaps tellingly – new to me and whose names I can’t remember or find in the publicity), an arena where no-one once would have invited Freud because of his reputation, amongst some women, as being abusive to women. As far as I can see it’s difficult not to see those relationships as containing the elements of abuse.

It is a film I want to see again and/or own when the DVD is available from EOS. It towers above some other EOS companion films. But it does so for the reason that it focuses on one exhibition and its characteristic spaces (at the Royal Academy) and that it pursues a theme about the nature of self-portraiture, even calling in James Hall to do a splendid comparison of theme and technical detail in both Freud and his greater influence, Rembrandt.

It is important that you can see models of some of his portraits that often contain an element of reflective self-portrait – the capture of the painter’s stance, his part-reflection or shadow – are seen, both clothed (Martin Gayford, Peter Bowles, and David Dawson) and in the case of the gay comedian, Leigh Bowery, unclothed – just so we can guess at how and why these paintings often distort to reveal a larger truth. The excruciating positions and rigorous requirement made of sitters comes across – especially in archive film of David Dawson.

There is an interesting moment when John Richardson, the recently deceased biographer of Picasso, explains how the term sur-realism (painting the real as more real than the real – ‘my aim’ says Freud in return) became under André Breton surrealism – capturing the dream symbolism underlying conventional reality. This has importance for early Freud and this subject is dealt with well in the film, with many lesser known early self-portraits showing a Freud many of us have not fully seen. This Freud clearly painted ideas in ways that became anathema to him but which might have influenced Hockney. The use of a finished surface here is well contrasted by the use of impasto overlaps in later oils, owing a lot to Rembrandt but also pointing at Frank Auerbach. Whether you know Lucian Freud’s work well or less well you’ll benefit from this great film. As I said already, I can’t wait to see it again.

Steve

5 thoughts on “Reflecting on Exhibition on Screen: David Bickerstaff’s film of ‘Lucian Freud: A Self-Portrait’ (at Royal Academy of Arts, London) seen at Gala Theatre, Durham, Screen 1.”