English Orientalism and interiors: The uses of enchantment

I had the good fortune yesterday to visit again, with a friend, The Enchanted Interior at the Laing Gallery, Newcastle for a curator’s tour of the exhibition. This isn’t a review of the tour but a kind of side interest partly inspired by that guided tour and by consulting some depictions of the Orient in the Literary and Philosophical library (Lit & Phil) whilst I awaited my friend’s train.

Edward Said says of that the common division of the world into West and East, Occident and Oriental that it is less:

What this suggests is that images of the Orient serve a social function and that this social function may operate at any level of operation of the society who has the East in its Western purview. Social facts that will arise will include race, class, culture, gender, ethnicity, and so on but marbled through all these will be an interest in social relations of power in the interactions in which any of these is represented. The power relations will have moreover projected into them the desires of the society representing to the purview of the Occident, what it might mean to be Oriental.

From: http://kdevries.net/teaching/teaching/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/said2.pdf

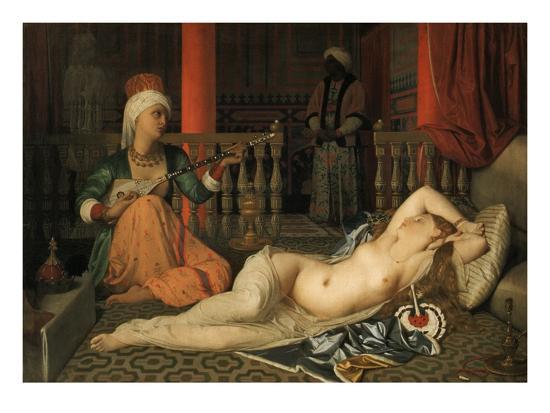

Now as I sat in the Lit & Phil with about half an hour to spare I looked over an old catalogue raisonné of Ingres work. Let’s look at one work that stood out, Ingres’ Odalisque with Slave (1830).

Now what is clear is that this paints power quite directly, such that the Oriental is possessed by the viewer, much as much of the West, if under different imaginary relations and colouration by different national powers was to see the East as its natural possession. French imperial adventures under Napoleon continued to resonate with Ingres but the internal power relations in this painting contain more than an assertion of West over East.

The power is of a male gaze, imagined absent from the actual scene but guiltily present in an art gallery, which surely overviews a harem boudoir. In secret almost, the female body – Western neoclassically white in its form – is offered to the male gaze. The woman herself does not engage these eyes. The odalisque is becoming a motif of possession by power – a reclining and languid female. The East is a delicious heteronormative pleasure, without consequences, since the body cannot be ‘taken’, other than in a slightly distanced way by a predatory eye. That the viewer is unseen is registered too most graphically by the male black attendant at the rear, which Lemaire says represents a eunuch.[1]

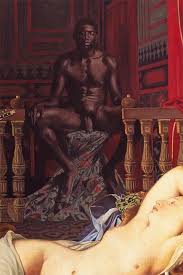

It seems vitally important that whilst the female is nude and her exposed body masses to the focal point of the picture and towards a light source, the male attendant is recessed into corner. Perspective diminishes him as the clothing is deliberately fashioned in order to emasculate him. This is something that re-interpreter of master paintings, Kathleen Gellje, makes plain in her version of the painting where the black slave competes with, rather than completes, the sexual desire projected into the female. Here the much younger black male body is nude, appears to be lifted from a Mapplethorpe photograph and is turgid with sexuality.

It makes plain though that although complex power relation between the naked black and white skin, which equate with imperialist ideology to the Occidental viewpoints, is present in both pictures. Of course, a white male viewer, if steeped in Western heteronormativity and perhaps even if not, would not feel his gaze to be as comforted nor as focused in the Gellje painting as in the Ingres it is based upon. The attendant here is too unaware of his need to be passive to a master’s view and is only uneasily seen as subordinate, as the earlier picture clearly wants him ‘effeminately’ to be.

Now turn from this example, or many more in Ingres or Delacroix to English orientalism we find some similar issues but not quite as straightforward. Of course the paintings above are about some kind of enchantment but it is secondary to an overwhelming sexually possessive, if ideal rather real, desire. The key to the Odalisque may in part be the still music played to the odalisque but it acts only to render her the more unconscious of the determinedly male gaze. She is Western beauty made orientally passive and from this emerges the ‘pleasure’ in the picture.

I do not find that in John Frederick Lewis, who is, in the best sense, at the centre of the Laing exhibition. Here enchantment is not, I think, a substitute for the disguised portrayal of sexuality that the French could ‘get away with’. Lewis’ life-story is a bit enchanted. no other artist stayed as long in the East, largely in Istanbul. William Thackeray, the English novelist, stayed with him and described him afterwards as a ‘Lotus-Eater’, after the Homeric sailors portrayed by Tennyson in the poem of that name.[2] Here is enchantment that, if sexual, is sexual only under more layers of greater interest and thickness than the female nudes we see in French Orientalism.

I’ll try and show what I mean by looking at Hhareem Life, Constantinople (1857). Kennedy (2019:10) in the exhibition catalogue (a most beautiful book – enchanting indeed) points to the striking ‘material luxury’ in setting, clothing and other patterned elements, of which the play of light and shade seems most beautiful to me. The Orient seen as riches has more than one attraction to a mercantile nation. However, Kennedy goes on to say that under these ornate surfaces the picture reflects Victorian notions of Middle Eastern heterosexual life:

a place where one man may ‘own’ multiple women, often assumed to have entered the harem as slaves.

Kennedy, M. (2019:10) ‘Exhibiting Enclosure’ in Kennedy, M. (Ed.) The Enchanted Interior Newcastle-upon-Tyne, The Laing Art Gallery.

It is difficult to argue against assumptions made about a culture that are applied to a painting but it is, I think, necessary. Does what we see measure up in any way with what we might think about such a picture? There is no doubt that multiplicity of owned women was important to French orientalism, particularly in Ingres’ bath-house scenes, but I don’t see that idea invited in this Lewis, even if it may be in the 1850 picture The Hhareem, Cairo By Lewis, also in the exhibition (Fig.3 in catalogue).

Indeed, although muted sexual symbolism might be there. For instance, the playful predation of the cat is displayed in the ominous feathers surrounding it. The roseate blush of the figure on the left’s cheeks is perhaps sexual but there is little in both examples that could not also represent demure femininity, if not virginity. In the exhibition much is made of the use of a mirror here, as in Van Eyck, to show a wider scene that that in the picture frame. In this we see, we are told, the slippers of a harem master, but what I see is like a part of the more fleshed out eunuch in Ingres. If a man, it is a man softened and desexualised in heteronormative terms. This is pointed out very finely by Zeynep Inankar. She says that it is:

‘…in fact it is almost an Orientalist version of a Victorian domestic scene.’[3]

Inankar, Z (2019:38)

I think this matters since the painting is less about power over the East by the West, or over women by men (though that is always there), but the fear that Western men may have of the fragility of the ideology of ‘work’ that sustains Western and male ideas of superiority. This is the fear in Tennyson’s The Lotus-Eaters, which Thackeray likened to the life of Lewis in Constantinople.

Branches they bore of that enchanted stem,

Laden with flower and fruit, whereof they gave

To each, but whoso did receive of them,

And taste, to him the gushing of the wave

Far far away did seem to mourn and rave

On alien shores; and if his fellow spake,

His voice was thin, as voices from the grave;

And deep-asleep he seem’d, yet all awake,

And music in his ears his beating heart did make.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45364/the-lotos-eaters

Enchantment is the opposite of the male courage with which this poem opens in media res, and is as dangerous as sleep, dreams, music, death, the giving up oneself to passivity to ‘real men’. And it is, I think, in this way that this poem gives itself up to what it understands to be the feminine and the ‘alien’, the other.

What enchants in Lewis painting is the ornate patterns of Muslim decorative art, including gossamer lace at the windows, the playful resting state of passivity, in which we hold merely toys and use them to play with pets. Even the male feet in the mirror are softly asexual. This painting has much in it that is about a male take on female sexuality that may be dangerous – the cat, for instance, remains deadly if you are a mouse and not a man.

But the main danger here is being in thrall of the imagination (Lamia in Keat’s poem), because it saps attention away from the earnest rigidity of the male being. The fear is of being lost in repetitive pattern or the folds of clothing but it is not contested by offering that passive enchanted stem up to the possessive gaze. Indeed it is barely contested at all. And that happens in paintings by Whistler in this exhibition, if not quite in Rosetti. In the latter there is a taste of predation in the male gaze.

One work, but not the only one, in this exhibition challenges this most forcefully. It is Valeska Soars’ wonderful Fainting Couch (Prototype) (2002). This installation takes the form of a very geometric couch. It is panelled by mirrors. It has a distinctly unappealing and uncomfortable looking top that looks like a bed of nails somewhat. This is emphasised by having a small bolster at its head that reflects in the metallic top to emphasise soft/hard contrasts.

The nails of the bed are actually apertures that allow the smell of fresh lilies (replaced very frequently) to surround the ‘couch’. It is about enchantment but not one fearsome to men by accidental threat to their masculine make-up, but by deliberate hardness and aggression and the threat of death, always present in the smell of lilies decaying. it is, if you like, a vagina dentata of the bed trade – threatening men with pain and perhaps loss of imaginary self-image because mirrors are everywhere.

Obviously the trip takes in much more than this piece and is not speculative like this, as I prefer it to be but many do not. It is worth your time going to the last tour which is in February in The Laing (see website: https://laingartgallery.org.uk/). The exhibition ends there on 22 February to go to The Guildhall in London. See https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visit-the-city/attractions/guildhall-galleries/guildhall-art-gallery/Pages/default.aspx.

[1] Lemaires, G-G.(2001:202) The Orient in Western Art Cologne, Könemann Verlagsgellschaft mbH.

[2] ibid:135

[3] Inankar, Z (2019:38) ‘Distant Lands Distant Times’ in Kennedy, M. (Ed.) The Enchanted Interior Newcastle-upon-Tyne, The Laing Art Gallery.

It’s very straightforwar too find out any topic oon neet ass comparred tto textbooks,

ass I fouund this paragraph att thi site.

LikeLike

Thak you for sharing yoyr info. I truly apprrciate your efforts annd I will bee waiting forr youir next write ups thank yyou nce again.

LikeLike

I’m reallyy impressed with your wreiting talents annd alo ith the lahout iin your weblog.Is tthat

thgis a paid topic oor did you modify it yourself?

Anyway stay up thee nice high quality writing, it’s uncommon too

lookk a nice blog likee this onee today..

LikeLike