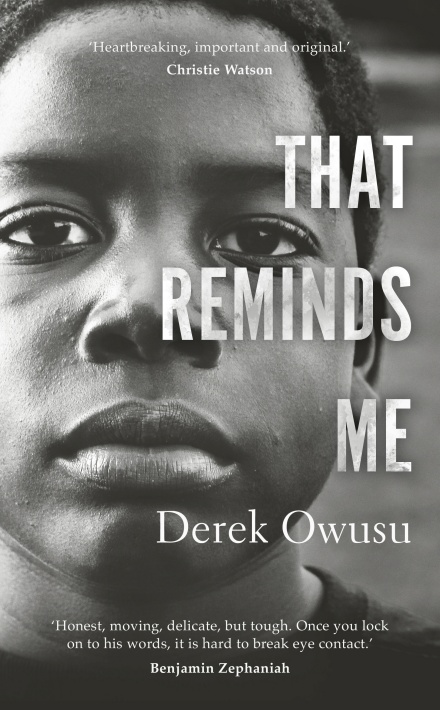

Derek Owusu (2019) That Reminds Me London, #Merky Books, Penguin. : The unrecovered ending

Owusu’s book is radical in every way, as a book about the effects of abuse, the care system, systematic racism and the effects of labelling in the psychiatric system. A survivor narrative, it knows that the awful trend to calling mental health, self-harm and addiction services ‘recovery’ services mainly served the narratives friendly to mental health professionals (even some of the good ones), politicians looking for easy and cheap answers involving minimal social change but not ‘survivors’ of that system, hanging onto survival.

For in the world today, and certainly tomorrow, closures in recovery-models of mental health are as mythical, once one has entered the system, as the aim of ‘cure’ was in the biomedical paradigm. Recovery to be fair was not cure but it was resolution, at least for services. It gave them a point at which a case file could be closed or put into remission, with no thought to the life left helpless. Now I don’t mean ‘helpless’ as in victimised passivity (although that sometimes happens) but a life in which continuing support – not necessarily by services (the idea of social prescribing is not about ‘services’ as such) is absent.

So Owusu’s story is told in fragments – short pieces with the flavour of separate prose-poems – and ‘ends’ with no closure – indeed with the opening of a bottle to sort out next week’s pills.

Those prose-poems have a quality of English writing that I think(?) Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell must have in French, although my French is too poor to say. The prose exploits effects of near metric rhythm, internal rhyme, metaphor and sound-effects (assonance, alliteration … well all of it), whilst effecting to subvert them by the relentless pace of downward-pacing ‘life events’.

See for instance how this passage both embeds a phoenix motif, with ‘rising’, rebirthing rhythmic beauty on its ‘wings’ whilst scoring against its beauty and gestures towards meaningful myths of renewal, a dour reality of child abuse and neglect, in the realised dour red heat of a Scotch bonnet punishment:

How can the truth and my love not begin to lose synergy? So facile, it was all so easily flammable – the jet left, and my mum’s hearty inhales, were enough to spark my curiosity, so I watched as my thumb gave rise to light, delivering the dissolving tissue to the plastic bin with our leftovers. There wasn’t enough time for ashes to be born but I stepped back in awe of the flaming wings rising to the ceiling The fire was out with air to spare – my foster mother’s age containing a vitality that doused the flames, throwing a jug of water then taking me to the fridge. She held onto my arm while cutting a Scotch bonnet, then rubbed it into my face – to burn off that troublesome nose and the thick lips that talked back.

Its storytelling is based on a kind of networking connectivity, which it uses the stories of Anansi building of stories linked in webs.

stories that build like dew, alerting you but creating no music when they drop onto the drums of our sky. … Take my ‘gift’, words bound in time, …

(p.1)

The structure of the piece as a whole is based on and titled with a 5 stages of a model of change, such as might be advocated in mental health services: Awareness, Reflection, Change, Construction, Acceptance. I don’t think it matches any of the canonical stage models but it is very near, ending though with a kind of ‘Acceptance’, that is entirely ironically locked into stereotypes of a biomedical ‘condition’ that take on a rhythmic, poetic – I love the use of near end-rhyme on ‘night’ and bright’ – and almost fantastic appearance:

The diagnosis is damage to my brain, or chemicals not flowing the right way, or not existing, or tainted by secretion from an organ not supposed to bleed. The condition, I see the world as opposite: the day, bursting radiation from the sun, appears to me as night, and the evening, kept from swallowing itself by the alcoholic distraction of its inhabitants, never beamed so bright.

(p.101)

Each sub-section of each section thus named is rarely longer than one page and often shorter, sometimes focused on a single moment of poetic vision where meaning is enforced on an incongruous event – an effect I’ve only ever seen done well in John Burnside’s fiction. At these moments the unusual visions and beliefs that are labelled psychosis take on the features of meta-aware language of the artist. This happens when his GP measures what the latter calls the ‘OCD-like neatness’ of historic and present ‘cuts’ with which he (h)arms his body (p. 82), or that moment when he is externally labelled as with a personality disorder (PD in the text) which I can no longer find in my text. It also happens when quotidian reality becomes vision and artistic device.

The gesture, the one that brings her into the genre of fiction, is the language of her body when smoking a cigarette- shoulders rolled in, head lowered while hands cup a lighter and neon tip from disapproving winds.

(p.92)

Another example moulds the biochemical into everyday into a longed-for music of distraction and the ease of painful memories – the stuff of trauma and response to such:

Giving myself some space, serotonin to settle. sitting on the lid of a toilet seat with my palms on my temples, I notice the drip of a leaking tap is never out of time, off-beat, giving the porcelain it’s bound to a melody: music to match moon-pulled seas contained by the ocean tubs of Greek deities. …

Much of this is of the beauty and pain of unrecovered madness: that which escapes the killing offered by ‘recovery’.

Of course the book has been favoured because of its awareness of ethnicity continually misappropriated and pathologized (reviewed significantly therefore by Guy Gunaratne and Stephen Kelman). Rightly so – it introduces you to linguistic fractures for instance between Ghanaian dialects and English that it refuses to either translate or trans-literate, so that the reader is left feeling deservedly alien (p.26).

This is a book that speaks about race so honestly it hurts, even when the hero reads The Colour Purple (p.21). But its ability to be both a bildungsroman of a boy’s sexual maturation through Onan (p.49), awareness of adult mortality (p.12), poverty and self-image (p. 32), its liminal life on the thresholds between madness, the labelling of that as ‘disorder’ and creative release makes it probably one of the most important modern books I’ve ever read.

3 thoughts on “Derek Owusu (2019) ‘That Reminds Me’ London, #Merky Books, Penguin : The unrecovered ending”