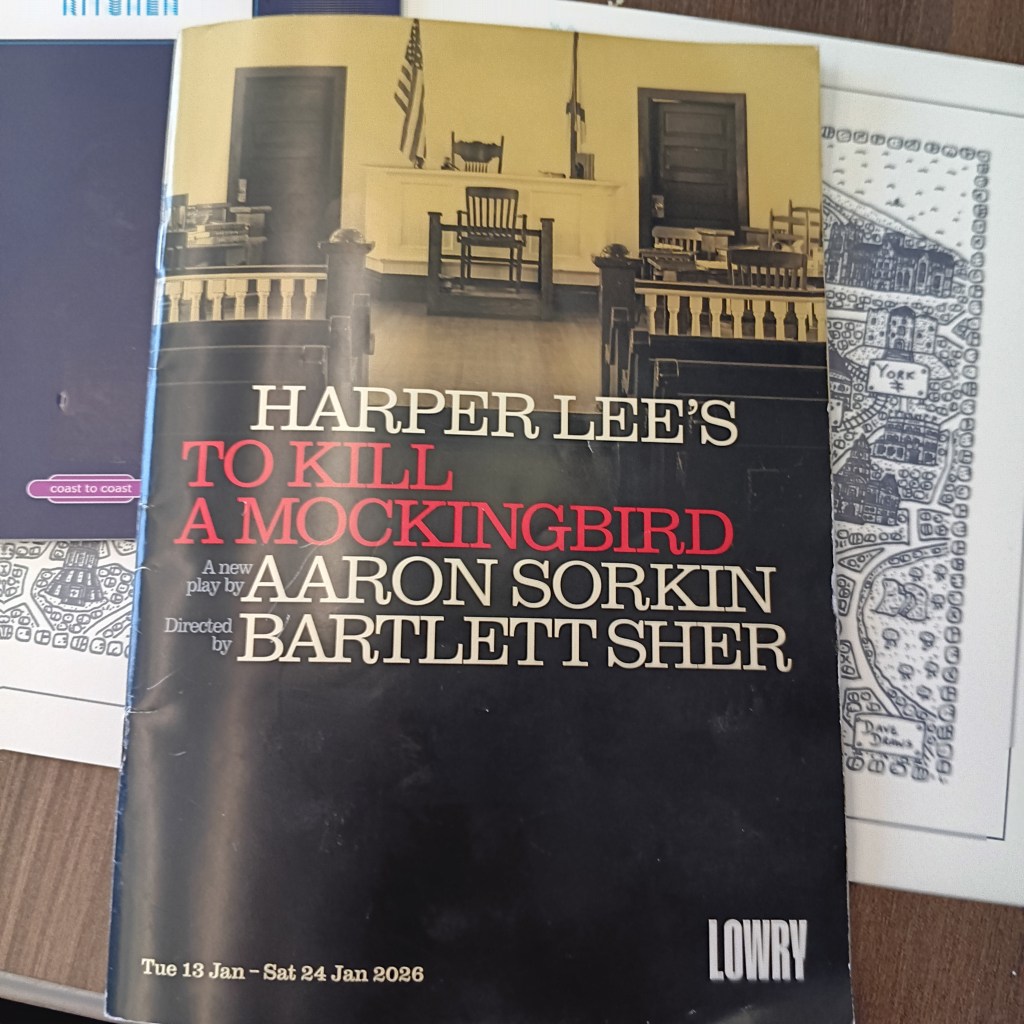

I wrote a preparatory blog once I booked to see this play. You can access it at this link: https://livesteven.com/2025/11/25/boo-only-comes-out-at-night-so-says-jem-finch-in-the-1962-film-of-to-kill-a-mocking-bird-what-does-it-take-to-make-darkness-visible-this-is-a-blog-preparing-me-to-see-the-touring-produc/. In this blog, I say the following regarding the treatment of Tom Robinson in book and film:

Tom is trapped. Tom cannot explain away his apparent ‘sign of guilt’ without exposing the contradictions in the white morality in relation to both black people and white women, and this, as certainly as the terrible sin of a Black man pitying a white woman would have condemned Tom anyway. When Atticus sums up before the court, he attempts to explain this predicament and accuse white society of thinking of Black men in terms of stereotypes or an ‘evil assumption’ of Black perfidy, but to defend Tom, Atticus can only describe another Black stereotype – the one given by Lee’s writing as a ‘quiet, respectable, humble Negro’ [9] – but it hardly gives Tom the complexity of Boo Radley, another ‘victim’ of stereotypes, who remains as mysterious as he was when the book ends.

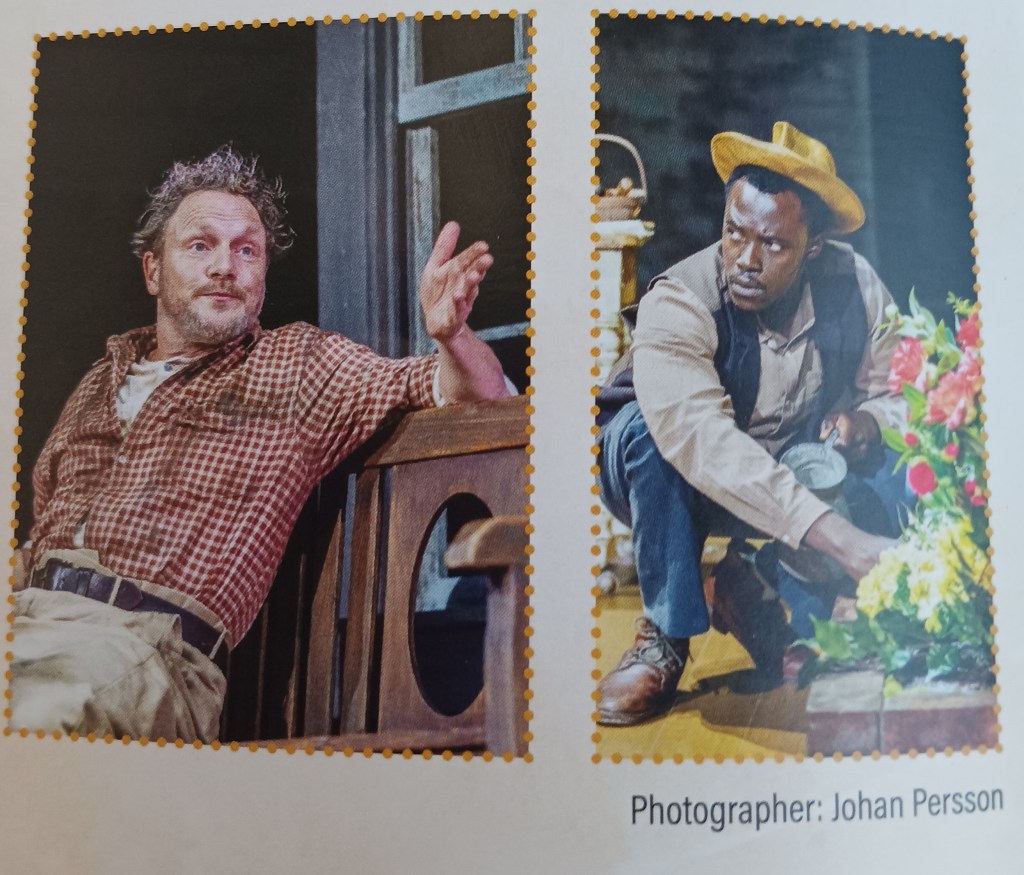

At the production I just enjoyed, there was a post show question and answer section attended by the substitute touring director, a lecturer on the history of the Southern States of America and the actor playing Tom, Aaron Shoshanya. Tom was a good actor, rather reactive in his characterisation in ways that nuanced the role,sometimes. He said each night he reacted differently in response to a difference of tone in the playing of another role: Tom remained still passive because the alternative is death, as the story makes clear, but sometimes shadowing into visibility pride and humanity that must be hidden, sometimes just passive aggression against white appropriation of his interpretation.

In the Q&A session, there was a fine instance of the dynamics of passive aggression, although strangely skewed to the most micro of oppressive dynamics. Sure that she was being ignored by a predominantly white audience, a young black woman protested that her early show of a desire to speak was ignored, made her way to the stage to be supplied a microphone by Aaron Shoshanya. She spoke of her voice having been ignored, of the ‘easy’ and platitudinous capacity of white audiences to ‘like’ dramas that were in content a reflection of her much more difficult life, of what she interpreted as a smugness about the issues. I am not sure how this might have been registered, though, for me, it seemed more symptomatic than an address to substantive issues, though her question to Aaron about the levels of support for black actors playing this role was excellent, its force was lost. Aaron seemed satisfied by the support he received and praised it.

It was clear that this production was not taking some of the risks of its earlier outings, where, for instance, the actor playing Tom Robinson was subjected to the same racial oppression from the actor playing Bob Ewell, as the relation between their roles alone assumed. The programme contained a fine essay on the significance of Aaron Sorkin’s revision of the story by the finely well-qualified for this task, Afua Hirsch.

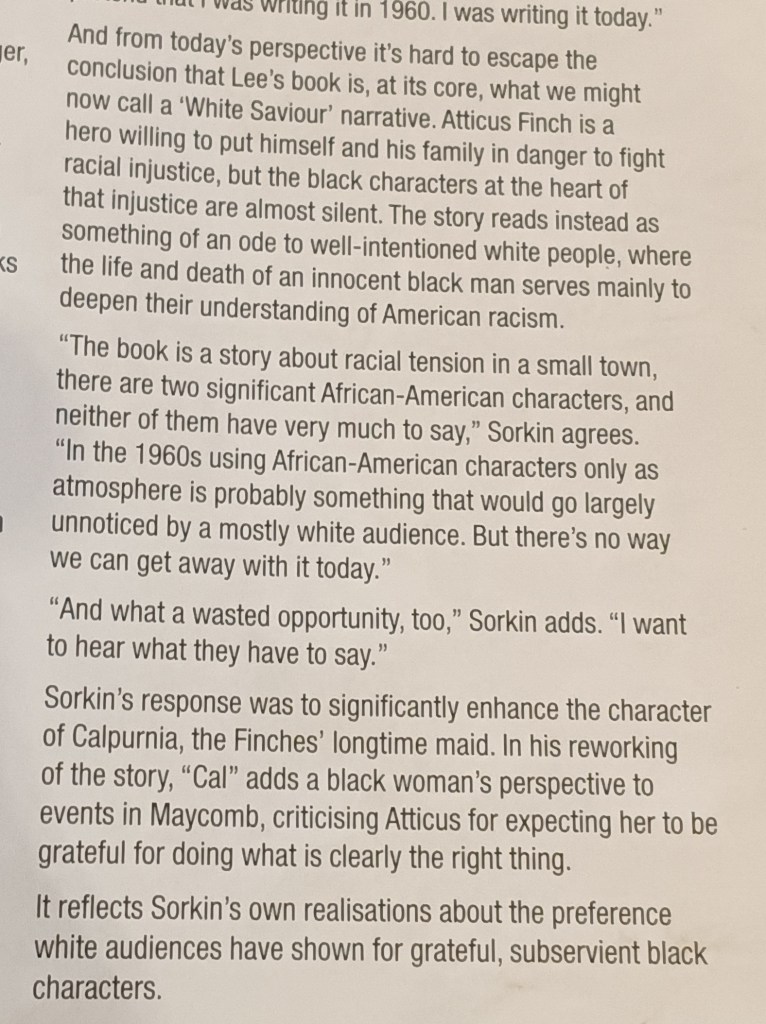

Her essay takes on, but with finesse and authority I don’t possess, some of the issues I had tried to focus upon in my blog. Here is what she says about the underlying racism of the ‘White Saviour’ flavour of the novel in the eyes of contemporaries now.

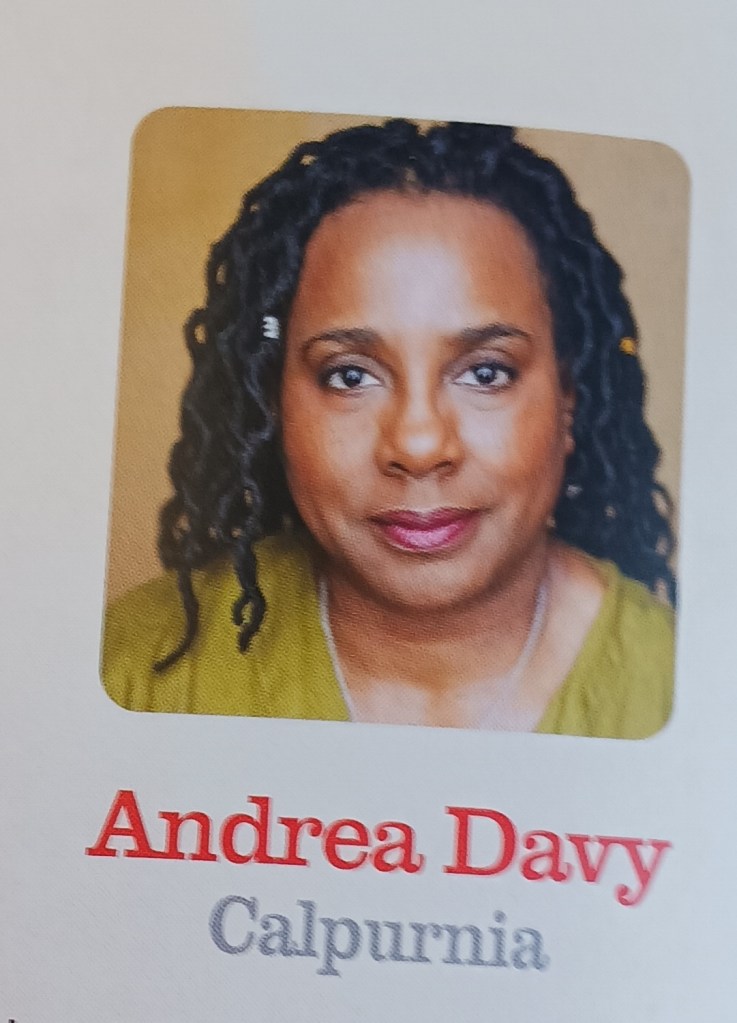

The issues here are not unlike those raised by the young woman in the audience, if addressed with less aggression, because soothed by the situational aspects of written and published discourse. But I read this after being shaken by the superb performance of Andrea Davy playing Calpurnia, who must have relished a part, as written by Sorkin, that ‘revenged’ every black maid role ever played in sagas of the American South in and since Gone With the Wind, where fine black female actors were reduced to baby talk in front of white superiors, in role and what the star system constructed as reality (Hattie McDaniell, for instance, playing ‘Mammy’ to Vivien Leigh’s ‘Scarlett O’Hara’).

Sorkin writes dialogue between Atticus Finch and Calpurnia in which the former tries to get under the surface of the latter’s discourse because he discerns ‘passive aggression,’ which he defines.

Usually used to pathologise, it is clear that the term here becomes increasingly used to characterise the presence of words that one might desire to be spoken if oppression and its watchdogs had not made them unspeakable without ugly consequences. As Bob says, none of the White people enacted in the courtroom scene have ever had their talk .monitored because they could be made. To accept the label, ‘nigger’. Aaron’s Shoshanya revealed in tje Q&A that in East London he had never heard the ‘N-word’ used of him in his youth and was shocked to receive it the first time on stage for this play as Tom Robinson.

There is a recognition in all this that Harper Lee’s must be forgiven, for she knew not what she did in terms of fostering racism that might now be feeding into Donald Trump’s discourse.. a rather good biography in the programme says this:

This drama begins to sideline somewhat Scout, though fabulously played, as it must if we have to critique Harper Lee’s obsessive love of her father, the model of Atticus. Sorkin gives more credibility to Jem (fabulously and sensually played by Gabriel Scott) and forces Atticus (what can we say more in praise of Richard Coyle) to change, to take in Calpurnia’s point of view as his own. Here is what Hirsch says:

The words that claim the film ‘fleshed out an archetypal post Gone With The Wind view of the American South’ must surprise some Lee fans. But this is precisely why Aaron Sorkin needed to draw out of the Calpurnia role the suppressed silenced voice of the Black South. He does it brilliantly, and Andrea Davy does not let him down.

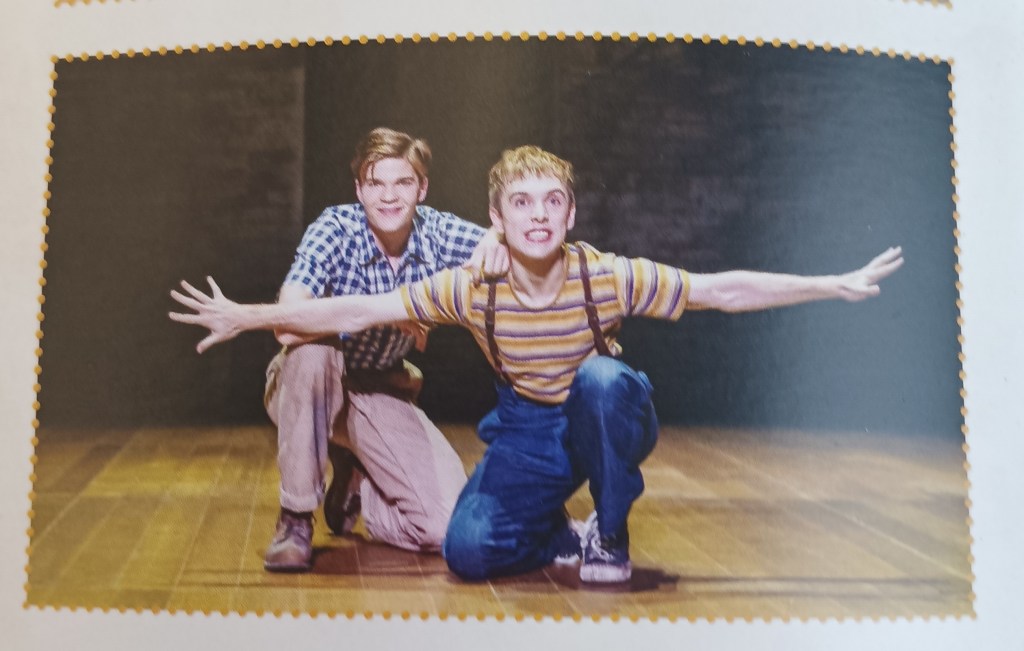

There is another change I noticed. The biography in the programme makes something of the fact that the character Dill was based on the real Truman Capote.

My feeling about the production is that the wonderful Dylan Malyn draws out of Dill the inner Capote, even enhancing the returned erotic pull he feels to Jem, as his only substitute for Scout, being not the ‘marrying kind’ as he says. Scott has enough nuance to even further enhance this bromance into a kind of politicised romance, for Jem is the political driver of the White awakening in the play.

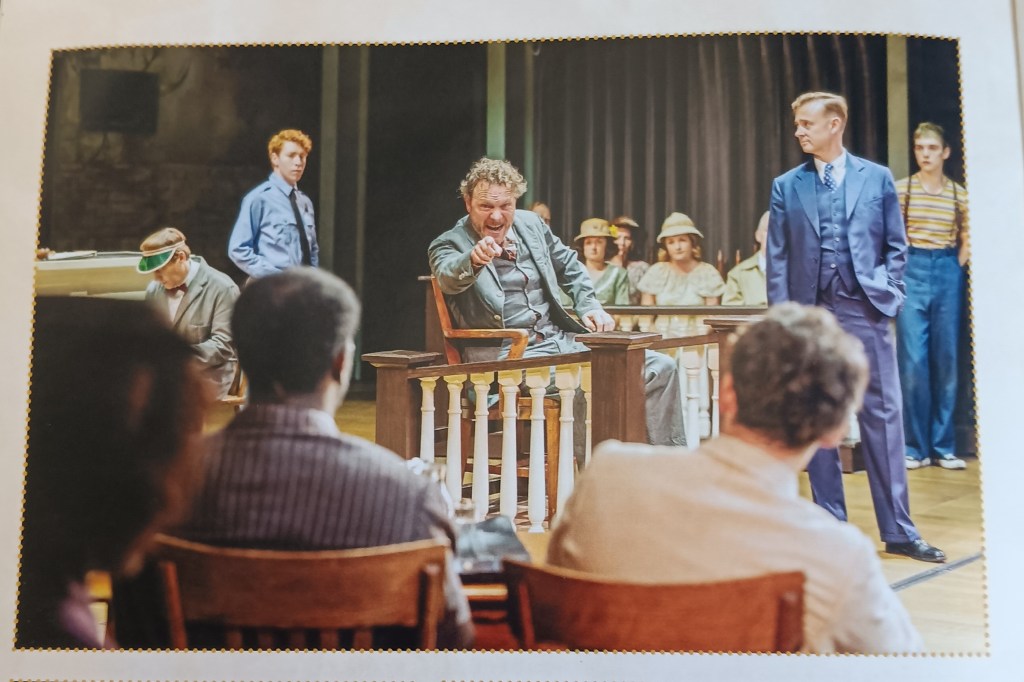

This is a superlative production. It is still touring. If you can, see it. And courtroom dramas … Witness Ewell turning against Atticus below.

Of them, this is a star.

With love

Steven xxxxxx