Richard Holmes is the literary biographer of the age, timing that age from my own time of literary awareness, and he, at last, has reached out to Tennyson, if confined (probably thankfully) to the Young Tennyson, before that poet became wrapped around with the populist British imperialism that most harms his reputation for people like me and stopped me loving this great poet for many years.

At school, an English teacher, Geoff Moutfield, who was my model of reading at the time, would recall F. R. Leavis, during his time at Cambridge savagely declaiming the early lyric recording the loss of Tennyson’s beloved Arthur Henry Hallam, but not included in In Memoriam, ‘Tears, idle Tears…’, as the prime example of a mechanical repetitive rhythm in which there is no premium on meaning, only vaguely sentimental effect. I came back to Tennyson through an even more charismatic teacher, Mrs Antonia Duffy, aka A.S. Byatt the novelist, whose essay on Maud I still revere, with its grasp of the role of sound imagery, the superior knowledge of metrics couterpoised with rhythm, and the role of the heartbeat’s variability as a biological model of how sound might illuminate the human dramas which the body senses in its darkened passages.

As Byatt says in her essay, and did in her lectures, the poetic of analogy derive from Wordsworth’s grasp of the need in poetry as nowhere else to defy the notion that ‘imagery’ is solely a visual and objectifying phenomenon. Wordsworth, in his poem on Tintern Abbey, tells us that landscapes are far from being visual and, if auditory too, not only in terms of external sound like birdsong and the sound of running water. To make his point, he uses the analogy of how a ‘landscape ‘ is felt in a ‘blind man’s eye’:

As is a landscape to a blind man's eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them,

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind

With tranquil restoration:— ...

Not felt ‘along’ the blood vessels and ‘in’ the heart, as one might expect, but with those locations reversed to indicate how heart and blood vessels work together to invent unconventional interior space, where the vessels of stasis and flow are reversed in effect.

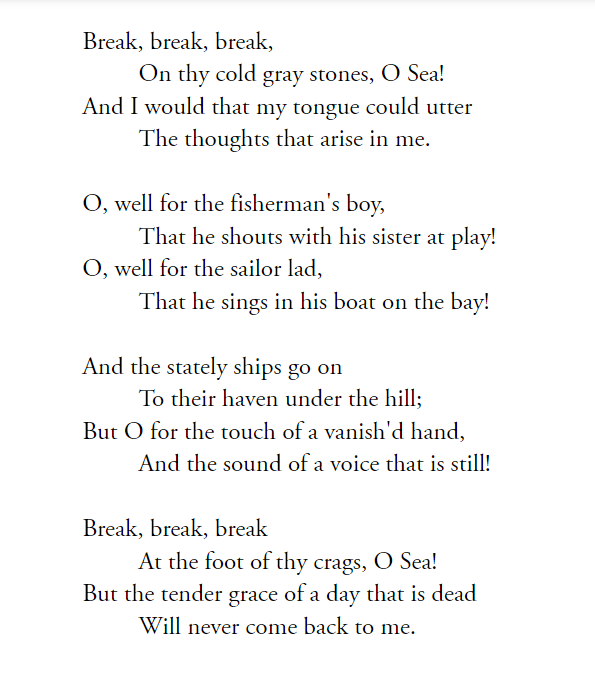

Holmes rescues another poem, often used as an example of the same meaningless sentiment as ‘Tears, idle Tears…‘ by our beloved English teacher, ‘Break, Break, Break, …’ where word repetition and rhyming variation mimic waves breaking. Breaks are relocated in the reconfiguration of space and time in wave theory, as propounded by Mary Somerville and other physicists:

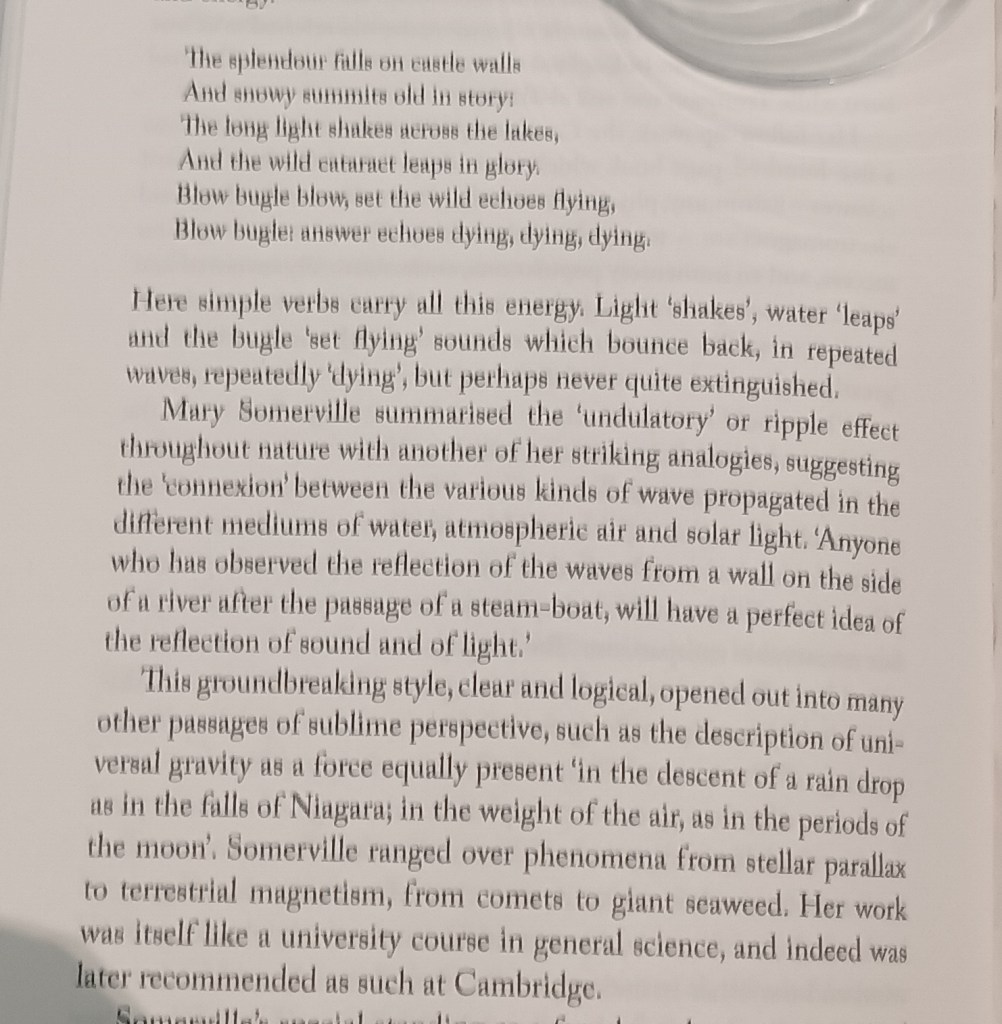

It isn’t exactly what Holmes says about this poem in paeticular (on page 104f.) but rather what he says about Tennyson’s descriprively using scientific theory as evoking a world of events beyond normative consciousness of space and time, the things that Mary Somerville found for him in her exploration and discursive explanation of wave theory, here applied to another lyric, one from the otherwise lamentable The Princess, a famous detail of which is printed and commented on in detail.

The repetition of simple words and repetitive phrases is true of the Break lyric too, and significantly deepens what Holmes says this poem does; which is to contrast the meaning evoked when we speak of either a heart or a wave ‘breaking‘. The minute cycles of energy that explain sea waves, snd their breaking against rocks and crags, which processes in themselves begin a descending spiral-cycle that leads to their decay, erosion and extinction in the long term of the rocks and crags they break against. All this moves the imagination from apprehension of things too minute for perception to things far too vast to perception in accustomed notions of space and time.

That latter perception is a cruel reminder that all things pass from significance, even the breaking of a heart felt to be of maximal significance to one individual thinking of another beloved individual but now dead, where love itself might be extinguished. It highlights the superficiality of meaning in the temporal joy of a fisherman’s boy, sailor lad and even a ‘stately ship’, a ship of state indeed.

At last poetry of a supposedly simple and ‘mechanical’ nature, is shown not to be such, and how much more for the lyrics of In Memoriam, and their ever suggestive, never ever certain sequencing and other patterns. This was a wonderful book to read on the train to Manchester today with the ever bold and bouncy student banter of my fellow passengers around me.

Tennyson was sometimes good at performative banter as well, just as he was at performative gloom.

Read the book. It’s beautiful. Xxxx

With love

Steven xxxxxxx