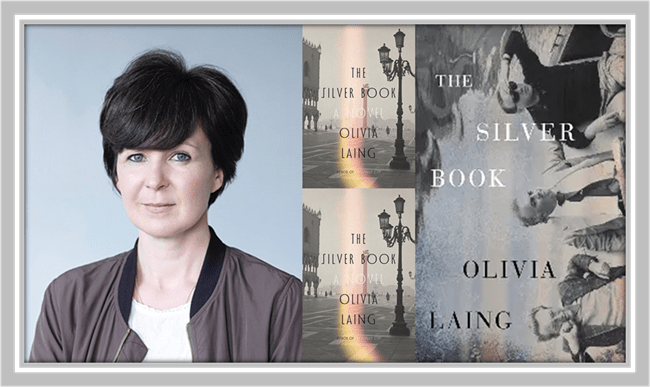

In a cold Italian winter with frost on the windowpanes, Nicholas Wade, art student and former rent boy, and perhaps a murderer, burrows into a ‘red brocade’ in Danilo Donato’s hotel room making it seem a ‘scarlet cave, the same colour as the inside of an eyelid’. As Nicholas flips over, ‘presenting himself for consumption’, he thinks of his situation as a mutually nourishing dinner date: ‘Night after night in the red and white bed, a feast for two’.[1] Olivia Laing’s The Silver Book is a feast too, enough for any ‘greedy boy’, provided you also need to feed the need for the illusion of eating the sweetest shit ever to be the product of ‘authentic illusion’ without the response, so over-learned it feels as if it is ‘natural’, of disgust.[2] But as with any indulgence of queer delight, it is a book that might best be considered to open ‘a door on to the past, and something is moving down there in the dark’.[3] This is a blog on the queer delight of forbidden knowledge, recovered from an imagined Hell, and other underground space, in Olivia Laing (2025) The Silver Book London, Hamish Hamilton / Penguin.

My title for this blog alone will tell you that I consider this book as an infinitely reflexive examination of half-understood phenomena: in which common experience, like that of eating and appetite, and some larger and /or queerer variants of it, are mixed up in authentic illusions that are perhaps its manipulated reflections in the world of desire and that appear to fool the eye as deflected onto the planar surfaces of a mirror of the camera’s photographic product, so that these impenetrable surfaces give way to feeling of something apparently penetrable, as in a dream, the theatre or the cinema. Whilst told through the very guarded point of view of Nicholas Wade, about which remains reserved, the book often shifts into the delight of the images of a shapeshifter (too various for a doppelgänger (though he describes himself as such in nature) Dani, based on the historical character of the costume designer (and set designer for Fellini too) Danilo Donato.

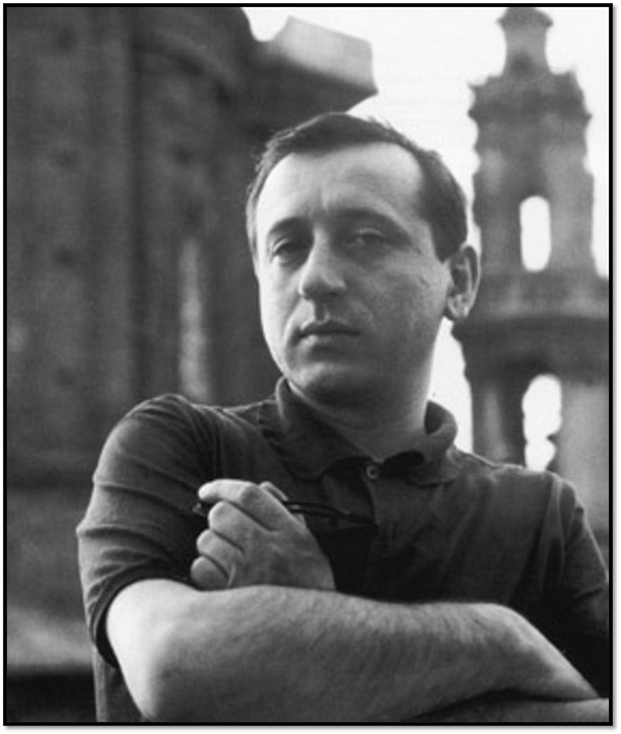

Through Nicholas eye’s, as he wakes up Dani’s bed, the morning after being picked up on the street in Venice, because his drawing and his pallor attracts the illusionary designer to him, ‘the man bending over him’ seems real enough, and to fit the photograph of the real man above (though some parts described above are occluded from the photograph:

… unattractive, moon-faced and looming. He’s got to be fifty, heavyset, with sleepy eyes and a Roman nose in that strange, impassive, almost circular face. Broad chest, thick thighs, fat cock, a machismo intensified by the quick, queeny, almost mocking elegance of the hands.

Thus far the description is that of the entrained assessment responses of a rent boy (I use this term because the book is dedicated to the memory of Gary Indiana – see my blog on the latter’s novel Rent Boy here) prepared to see the ‘man’ from his surface and physical characteristics, with a sense too of the motivation for his adoption, enough needed, anyway to secure his relative safety, for elements of the man described certainly seem potentially to be threatening until we meet the mocking ‘quick, queeny ..elegance’ of the hands. But, as Nicholas awakens a little further (but not enough not to be still liable to sleep again) his eyes assess his setting and its indications, first of the punter’s financial assets (again a trick of the trade) but then of something surplus to that, a factor that leans out from the physical materials that are employed in the setting to the illusions it fosters and thence to the fantasies it enables. Those fantasies extend into one’s self-assessment in this present unexpected bit of luck for a rent boy. It is a morsel of prose I dare say most reviewers will refer to, or at least to the one jewellery-fashioned phrase in it:

They are in Danilo’s hotel room. For the past few years he has been a visitor to the rooms of the rich, but never to a space like this. It’s like a cavern under the sea. The water sloshes outside and a pattern like seaweed is stippled on the walls. The grandeur doesn’t intimidate him. Instead he feels like a pearl, finely set. He is looking at the velvet curtains, trying to discern if they are green or black as he subsides into sleep.[4]

One of the critics, Larissa Pham, uses as I predicted when I first read it that precise phrase about the pearl set by a jeweller but uses it to characterise the novel’s feel as writing and as a symbol of ‘mutual devotion to art-making’, although I think it a more multi-valent image than that myself: one that speaks of the unexpected luxury just discovered by the young man who has come to Italy ‘with nothing’, just as he leaves the cinema in the final chapter, having seen Fellini’s Casanova, in part to see if he can detect his role in it, ‘out into the sun’ unencumbered because: ‘He has brought nothing with him’.[5]

At the heart of the novel is Danilo and Nicholas’s relationship, triangulated by their mutual devotion to art-making. From the outset, Laing’s text conjures a tight, sensual world. Nico, on his first night in Danilo’s hotel room in Venice, compares it to an underwater cavern: “[He] feels like a pearl, finely set.”[6]

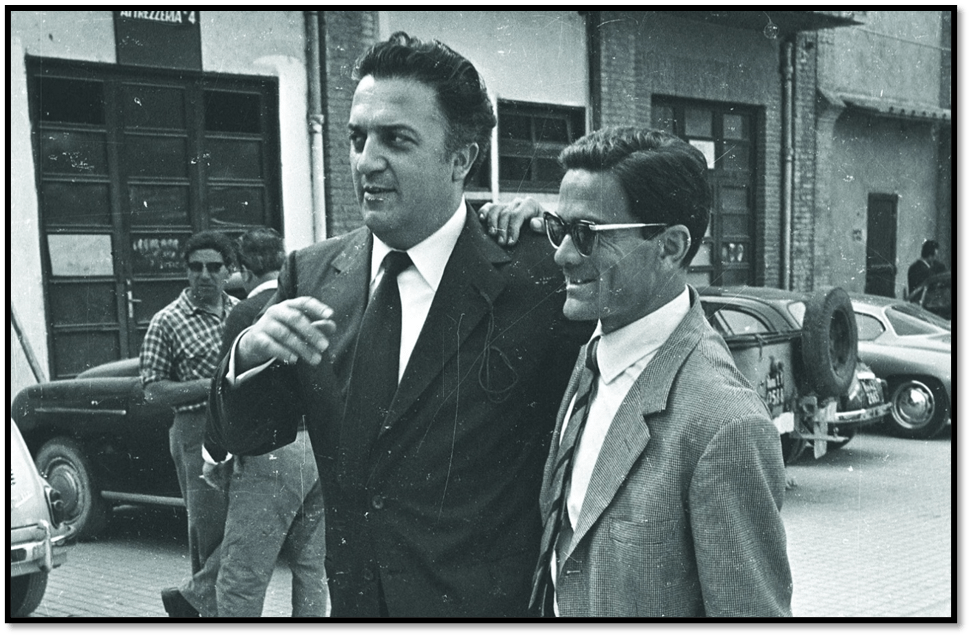

Though I use the idiom myself invoking the ‘heart’ of a novel is a dangerous act if we want to avoid missing those characterises that haunt the liminal margins of the novel too, for I think this novel has many margins that constantly go into hiding. The relationship between Dani and Nicholas begins in the shadow of the character representing the film-maker Frederico Fellini and, after it has ended, our last view of Nicholas is in viewing the Fellini film he worked upon with Dani, but it has in between an excursus, based on fact, of work on the film Salò: 120 Days of Sodom with Pasolini, episodes which end with the film ruptured and Pasolini dead. But in between it is the relationship of Nicholas – tentative and under-explored but much more exploratory of Nicholas’s thoughts about his own past life – with Pasolini that matters in the novel, in which relationship Nicholas is not a decorative pearl in a fine setting but, for once, the ‘wolf’ who is ready to skip ‘dinner to troll for boys’ , an act that for him ‘is too much, it is so too much that it is as if he has burst the bounds of his skin’.[7]

I find these passages somewhat disturbing for in them Nicholas takes as far as possible the tropes of Pasolini’s imagined life that monster him lycanthropically. Yet these are precisely the myths about Pasolini that depoliticise him serving both his fascist and Liberal-Democrat enemies, who many (including Dani) suspect of having Pasolini murdered for political reasons and made to look like the revenge upon him of the young men he ‘hunted’ (though in fact his cruising episodes were entirely voluntarily consensual).

Even this, Dani says,. Even this will be used against him. He has been assinated in the cleverest way imaginable. If they had shot him, he would be a martyr. But this: it looks as if he went out hunting for his own death. … That he was a low life who deserved what came for him.[8]

That part of the story ends with a picture (not the one below) of Pasolini’s funeral, showing the artist’s coffin surrounded by the ‘boys Pasolini fucked, the boys he listened to, found jobs for, helped, the boys he insisted on putting at the centre of the story’.[9]

Clearly, Pasolini, and Laing’s narrative connecting him to Nicholas, is very different to feel and style than that relating to Fellini. Likewise, the relationship between Dani and Pasolini as makers of art is different and less mediated through what Nicholas contributes to the creation of ‘authentic illusion’, the creation from poor materials, literally the materials of poverty, the illusion of grandeur and luxury: Fellini’s methodology is dubbed the ‘Arte Povera of the cinema’.[10] Sara Batkie writing in The Chicago Review of Books starts her review, as well one might with the stunning image of the contradictions in Pasolini’s interest in illusions of greatness that foster Fascism (and hence the choice of re-setting his version of the Marquis de Sade’s novel 120 Days of Sodom as Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom – Salò being the tiny home state the German Fascists set up for Mussolini after his disgrace) that deliberately exploit the poor many for the pleasure of the few and his kindly Gramscian Marxism, firmly located in Togliatti’s Eurocommunist Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI).

Batkie openly ponders why ‘homosexual desire’ becomes part of the representation of fascism, without coming up with answers – which answers I think are vital to understanding Nicholas and his relation to Pasolini, and the fact that the young English queer man is implicated (apparently innocently by his own account) with possible events leading up to Pasolini’s murder – the burglary of some irreplaceable film rolls of Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. Batkie does point out however, very usefully but with too many assumptions of fuller understanding than she possesses as a critic of this novel, that ‘The Silver Book takes a sideways approach to the tragedy’. She continues by saying that Olivia Laing is ‘much more interested in capturing the coolly hedonistic, intellectually adventurous lifestyle that Pasolini embodied than telling a straightforward story about the director himself. His part in the plot is tertiary but he casts a long shadow’.[11] It’s a point that’s useful but dreadfully misinterpreted for to see the relationship between Nicholas and Pasolini in this novel as merely ‘cooly hedonistic’ is to misunderstand entirely the approach to the representation of what remains dark, in more than one way, in the complex ambivalences within all forms of sexual desire at the level at which it operates as an appetite stimulant and its complex structural realisation as either or both, in various configurations, possession of another or a mutual sharing of each other.

Laing is not an accidental artist. There is a reason that Danilo Donato’s relationship begins by being mediated by artistic making commissioned by Fellini, and ends with reflection on Fellini’s obscure, AND NOT Pasolini’s direct, politics, methods and philosophy.

Federico Fellini (left) with Pier Paolo Pasolini in Rome, 1961. Photo Archivio Cicconi via Getty available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/olivia-laings-silver-book-pasolini-fellini-1234759609/

Whereas Fellini and Dano relate to each as masters of the manipulation of material into looking grander than itself, and then displaying its existential poverty in its performance – the way in which, for instance, Nicolas learns that Fellini had deliberately manipulated Donal Sutherland, as he does Dani, to show that we are all – a libertine like Casanova as mere exemplum – persons who have ‘no idea who they are, who is living inside the wrapper of a dream’[12] Felli, and Dani under his influence, is all about turning life into art, via means of artifice. Nicholas watches Dani to see how the latter ‘converts the real city they are travelling through into scenes from a story’, making ‘a pantomime city with its impossible architecture’ that yet exerts ‘a powerful pull on the imagination’, making the ‘greatest luxury with the trashiest, most impoverished resources he can find, the Arte Povera of the cinema’. [13] Some idea of these flashy effects can be seen in the dressing of Sutherland as Casanova below, adorned with mirrors and light, a face pulled by the caked make-up on it into full artifice and a necessity for the actor not to act so weighed down is he by artefacts of artifice:

Still from Fellini’s Casanova‚ 1976. Courtesy Everett Collection available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/olivia-laings-silver-book-pasolini-fellini-1234759609/

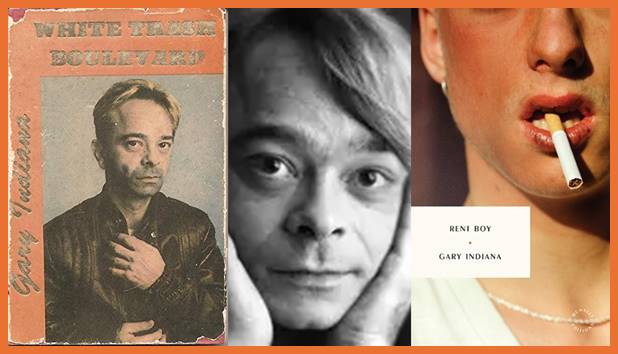

It shouldn’t escape our attention that this is exactly what Danilo does with the poverty of material in Nicholas – a pretty face and luscious thin pale body who brings nothing else to the feast but himself to cook and consume (we will come to food later). Here again is another reason for the dedication to Gary Indiana who made his art fro the trashiest and the available, especially that labelled ‘white trash’:

Danilo’s work for Pasolini is not unlike his work for Fellini although the former gives him more latitude though he confines him to costumes and properties not settings, the latter of which he takes on, borrowng Nicholas as his recreative eyes in Salò, himself. Shown the world of pretend-aristocratic bourgeois luxury as Pasolini sees it as his own life-story captured in peeling stucco, and uncomfortable memories of innocence shattered, and something he needs to reject, as he looks into some of the most amazing of the many telling mirrors in this book:

He catches his own face, swimming from a mirror, and thinks again of how good he looks among things he can’t afford. Better still, to be among them without wanting in.[14]

Dani’s work on Salò, is confined to his job, ensuring that the things he makes for use in it ‘look good on film’, but the prose at this point shows that what guides Danilo is something greater than Fellini’s intention to show that all life is poverty masked as something it isn’t, whether it is the life of the seventeenth-century Venetian aristocrat or a yearning star yearning to act brilliantly like Donald Sutherland. It is at this point that Dani finds himself used to open a door on a past no-one, not even himself, wants to re-see.[15] Dani really only loses his cool with Nicholas when Nicholas mistakes the behaviour of Pasolini with working class young me – nominated ‘boys’ – and fails to see the superiority of Pasolini as an artist who is of the people not of an industry, over all others who are ‘authentic illusion’ makers – practical or with philosophic intent. Unlike Fellini, who makes everyone, even fellow artists a ‘tool, an extension of the maestro’s privacy’ , even his audience, Pasolini’s art inspires the artist in others, in Donato a ‘sculptor’, and those collaborative artworks lean out of one person’s private world to uncover what is hidden: ‘Definitively strange, they have the function of dissolving the present, of creating a rent in time’.[16] And Dani does not share that perception of Pasolini with Nicholas, who never quite gets to know Pasolini, even though the director shares with him intense secrets akin to having killed another.

Nevertheless, Nicholas tries to render Pasolini ordinary, criticising him for using hair dye and for vanity, seeing something predatory in the master’s sex with boys (boys, after all, not unlike Nicholas), and a kind of voyeuristic fantasy about how Pasolini treats them sexually. Dani despairs of Nicholas at these times, saying of his words on Pasolini: ‘You don’t understand anything about him. You don’t understand what he is’. He ends his conversation there, for it is obvious that Nicholas has failed to understand what Danilo has already told him:

He’s an artist, Nico. I’ve worked with a lot of great artists, and he’s the most serious, the most soulful’.[17]

This is why I queried Pham’s metaphor for the book’s main theme or ‘heart’ of the novel, which I cited above: ‘At the heart of the novel is Danilo and Nicholas’s relationship, triangulated by their mutual devotion to art-making’. If we try and visualise that metaphorical graphic representation of the novel, its inadequacy is clear. So below I do that visualisation and compare it to one I find more adequate to the complexities of the novel’s duality, but, as a result, hard to follow. Nevertheless, here it is:

My diagram is double, with a radical disconnect between the feel and purport of the stories about Felli and Pasolini respectively. Nicholas is barred from access to knowledge of Pasolini’s art as a means of life and nation-making, which Danilo recognises, not least in Salò. Danilo and Nicholas ‘triangulate’ but only as makers of consumable art (as I will argue below) – authentic illusions of the real that look good. Nicholas only ever sees Pasolini as a man like him and, I think hates him for it. But I leave all that with you – ask me if you want more, for there is more to say. What Nicholas makes of the film Salò is what most might do in looking only at its stills (like that below), that turn bodies into pornographic consumables, just as Nicholas is.

B859AJ Salo o le 120 giornate di Sodoma Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom Year 1976 Italy / France Director : Pier Paolo Pasolini. Image shot 1976. available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/olivia-laings-silver-book-pasolini-fellini-1234759609/

It is only in working for Dani under Fellini that Nicholas grows in stature as a maker and as a person, confident and able to live his own life as well as serve those who feed him, but an effect of all of Dani’s fine cooking is that he grows in body too, as if fed by the consumable artifice that goes into the making of Casanova. At his first meeting Fellini points to Dani’s role in feeding up Nicholas: ‘’Get your boy some food, Fellini says. He’s far too thin”, before he pats Nicholason the arse, though without sexual intent.[18] Danilo always calls him a ‘greedy boy’: at one point he ‘can’t believe how hungry he is’, wolfing steaks and ‘forking up fried potatoes from Danilo’s plate’, before demanding pudding.[19] Dani’s cooking of a hare for Nicolas takes many days and is described over several pages.[20] Fellini’s art fattens, or fills out on meagre life likewise. In contrast working on Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is a wasting business for Nico, body and spirit, even though much gets consumed, even some very sweet consumable turds. Pham puts it very well, thus:

And yet, at the heart of the process lies something true: “Everyone else might be unaffected, mysteriously immune, but the daily descent into hell is getting to Nicholas,” Laing writes about his changing outlook during the filming of Salò. Unable to fully separate from the fictitious world of the film, Nicholas finds that fake violence is just as disturbing as real violence: “Things are becoming a bit too mixed.”[21]

Hell is very present in the Pasolini filming sections, as with references to Dante, and it is this connection to classic Italian art and to shared memories of the effect of Italian fascism that binds Dani to Pasolini, and makes him value the art so much. For Nicolas it has, as we have seen the opposite effect, and references to his white pallor resume, as with his memories of the death of his past lover – a closet heterosexual married man called Alan who ‘kept’ him in a flat full of mirrors and whom he might Nicholas see the ghost of Alan, who had been absent for some time. No wonder his body wastes: ‘Eating, sleeping, working, every action contaminated by this presence from the past’.[22] Contamination is a word Pasolini himself uses to speak of the way darkness seeps into his narratives. But for Nicholas Pasolini is inseparable from his guilt over Alan’s suicide / murder and his role in either. Hell is a return to a past which makes him identify with the boys ‘fucked’ by Pasolini, without even understanding that they are not, like him, in Hell. Nicholas needs an end to the Pasolini story to secure, I think, and end to Alan and yet again he may play a part in the artist’s death. As he tells Pasolinii, Alan in his mirrored rooms, like those of Pasolini and De Sade, feels Alan made ‘feel like doll. It made me feel I wasn’t quite real’.[23]

Now, although Fellini too invokes how artifice usurps the real – even the last love of Casanova is a ‘mechanical doll’, Rosalba, like the thing Alan and Paol makes Nicholas feel.[24] It is not unlike the feeling he has when he fears that in Dani’s parent house, he will be a ‘waif begging for scraps, it turns his stomach’. When like this Nicholas may be as much a ghost as that of Alan he sometimes sees. He can, after all, make himself invisible: ‘He’s a good ghost, practiced at the art of invisibility, the knack of becoming an object that eyes skim over’.[25] Having, however, dismissed one way of seeing this novel as suggested by Pham, I want to end by suggesting that another of her points – a well developed on, does contain the truth of the novel, except that, for me the ‘fakery’ of art she mentions is in Pasolini much more dangerous to Nicolas than it is in Fellini’s version, for it opens portals to the real and the past – though that past is an Italian one, shared with Danilo, of dark political history – for him that past is one in which he might sink, reduced to the poor trash or broken doll he thinks powerful creative people might make him into. Here is Pham anyway:

IN FICTION, ONE USES fakery, construction, and artifice to tell a deeper truth; cinema does the same. Watching a horror film, we know intellectually that no blood has been spilled, yet in the darkened theater we still scream in fear. Behind the scenes, the making of Salò, “the sickest film of all time,” is a cheerful romp, a set full of half-naked teens snacking on potato chips. Through Danilo’s constructions—period gowns; ocean waves made of plastic; murals made from candy that find a sinister echo in glossy chocolate fake shit—Laing takes the reader through the fakery that composes the real. In cinema, everything is made from something else.

All art is a product of its time, whether it chooses to acknowledge the circumstances of its making or cover them up with distraction and fakery. In layering historical moments—Italy in 1975, the 1943 Republic of Salò—and resurfacing them in this current era as fascism again emerges, Laing impresses on the reader how history impresses itself on the present. It cannot be escaped; the violence of the Years of Lead is what Pasolini saw approaching in the rear-view mirror. Laing forces us to ask: What future are we driving toward? [26]

Indeed Batkie says similar of the political tendency of the novel:

It’s () worth reconsidering in light of the current climate, when voices that speak truth to power are being increasingly silenced, or are terrified of speaking at all. “[E]very construction must necessarily contain a region that remains unseen,” Laing writes early on. If that’s the case then, as this potent novel demonstrates, whether in art or politics we must be careful who’s doing the constructing.[27]

For me though this layer of the novel’s operation lies sandwiched around the delight in artifice in Fellini, is a tragic space into which Nicolas won’t enter without much repression and suppression obscuring its power, as Fellini does, and that is an important point about the novel too. Better to be shut into the interior of an eyelid.

Whatever, read it. It’s a masterpiece.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Olivia Laing (2025: 62) The Silver Book London, Hamish Hamilton / Penguin

[2] Ibid: 10

[3] Ibid: 127

[4] Ibid: 12

[5] Ibid: 239

[6] Larissa Pham (2025 ‘Olivia Laing’s New Historical Fiction Sees Famed Italian Filmmakers Navigate Fascism’ in Art in America (November 3, 2025 5:00am) available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/olivia-laings-silver-book-pasolini-fellini-1234759609/

[7] Olivia Laing, op.cit: 90 & 91 respectively.

[8] Ibid: 234

[9] Ibid: 235 (the photograph is on ibid:237.

[10] Ibid: 49

[11] Sara Batkie (2025) ‘Art Imitates Life in “The Silver Book”’ in The Chicago Review of Books (November 18, 2025) Available at: https://chireviewofbooks.com/2025/11/18/art-imitates-life-in-the-silver-book/

[12] Ibid: 239

[13] Ibid: 22. 43f. 49 respectively

[14] Ibid: 83

[15] Ibid: 127

[16] Ibid: 76

[17] Ibid: 90

[18] Ibid: 35

[19] Ibid: 85

[20] Ibid: 92ff.

[21] Larissa Pham, op.cit.

[22] Ibid: 120

[23] Ibid: 142

[24] Ibid: 215

[25] Ibid: 5

[26] Larissa Pham, op.cit

[27] Sara Batkie, op.cit.