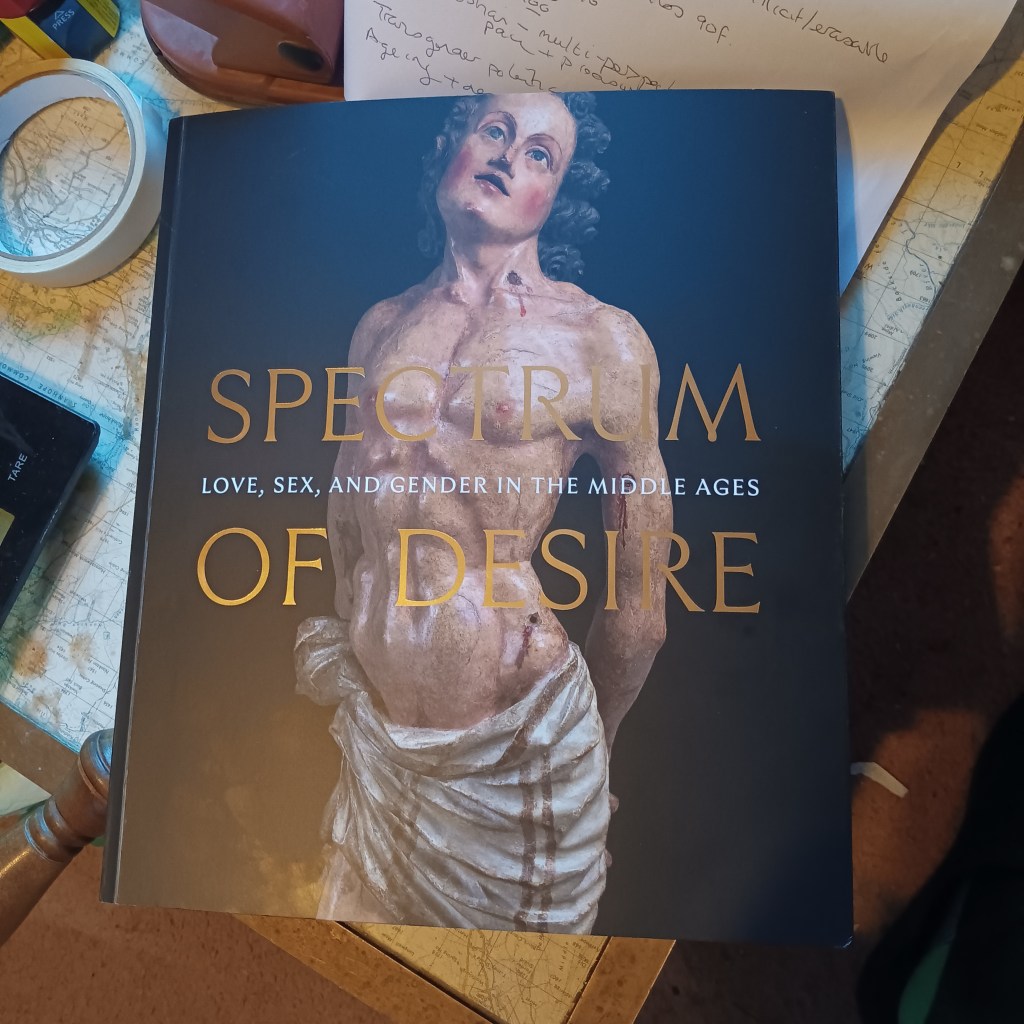

Late Medieval artists ‘shaped a society-wide fascination with all that bodies could become’: An exhibition and book charts the reasons why, using queer theory,there is an inevitable relationship between the desire to create art and ‘bodies that were betwixt and between, changed or actively changing’. This blog investigates The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new book by Melanie Holcomb & Nancy Thebaut (2025) ‘Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, And Gender in The Middle Ages’.

If I had a purpose here, other than to cement some degree of my own learning, it would be to recommend the book of which I focus on some selected aspects here. It is selective because I give nothing on the way medieval art challenges male authority through images of strong women, whilst illustrating stories meant to exemplify the humiliation of strong women – usually fictional ones, such as the lovers of Socrates and Virgil. But my interest is largely in the LGBTQI+ applications of learning about middle ages art iconography and the contradictory pleasures in it’s artistic treatment – often between an authorised cultural reading (opr one supposed to be so), and the visual art’s joy in making the supposedly transgressive and t0-be-condemned pleasurable, even when it might be meant to be ex hortatory or even painful. One essay deals with the joy the medieval sculptor might have had in work on the prone naked bodies that they carved into emergence, especially when their skills are usually employed in folds of clothing on figures.

Such ideas are speculative but the book give plentiful visual evidence for its judgements – a thing that a thin review in praise like my blog cannot do. So do read the book. It is more than enjoyable – even where you might question its readings, for it does make it clear that no-one knows how medieval people felt and thought things and that things we call norms – like binary sex/gender categories were as ‘modern’ and alien to them as the concept of the queer as a challenge to such norms. The authors convince me that to look for the ‘Medieval world-view’ is as pointless as its products are necessarily futile as hard knowledge. Moreover, it seems apparent that works of art were for medieval artists and craftspeople are not a reproduction of dogma, as they may be in the seventeenth Century Counter-Reformation art, but a ‘crucial site of experimentation, performance, and even play‘, that allowed for ‘gender-variant saints‘, as I shall – without the necessary arguments in the book – illustrate. The authors argue that ‘many aspects of the this period’s history are inherently queer, they buck our norms today but were often an integral part of the power structures of the past, most notably the Christian Church’. Karma Lochrie is cited as giving a good case that there ‘was no “normal” in the Middle Ages’. [1]

People think of queer theory as modern: as a reflection of new freedoms that have emerged from out of the morbid grasp, or safe holding (depending on your world view), of centuries-old norms. The point of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition from its holdings in medieval art is to read the Middle Ages again, that period in European history between the Decline of the Roman Empire to the Renaissance. The editors of the essays and illustrations in this book challenge that view and the assumptions it makes about Medieval thought and social being. In these pages, we see that love, sex and gender are seen ad embodied in fluid forms of bodies that vary around body shape and attendant meanings thereof, bodily marks and signature features, within, or penetrative of the surface, of the skin.

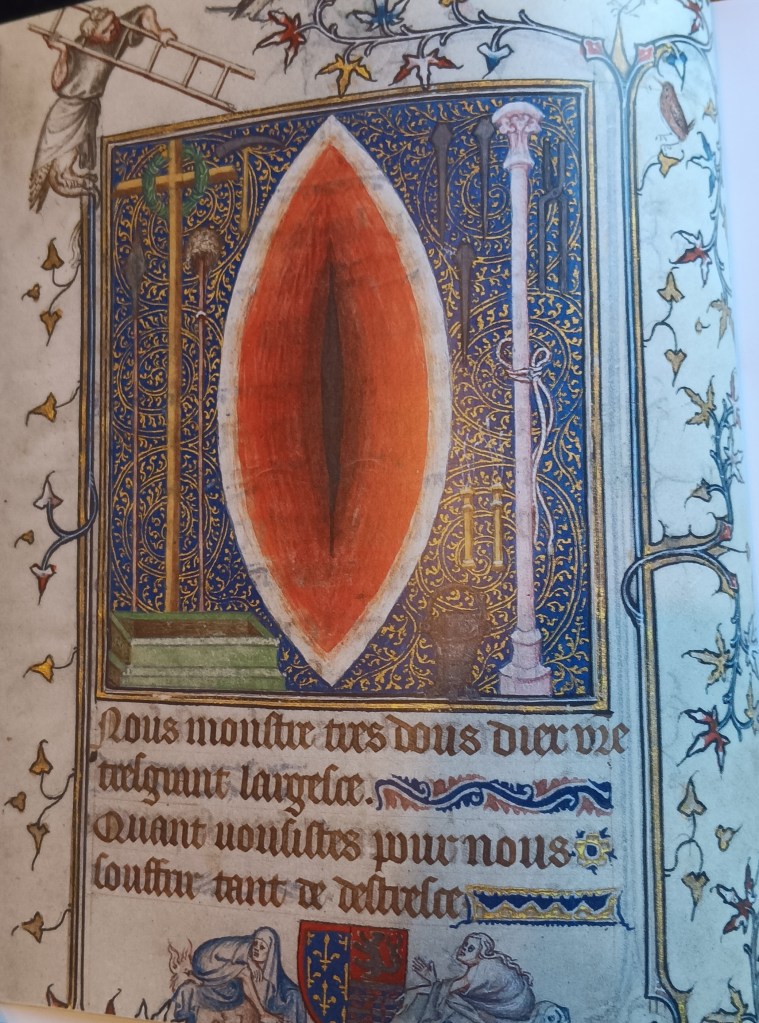

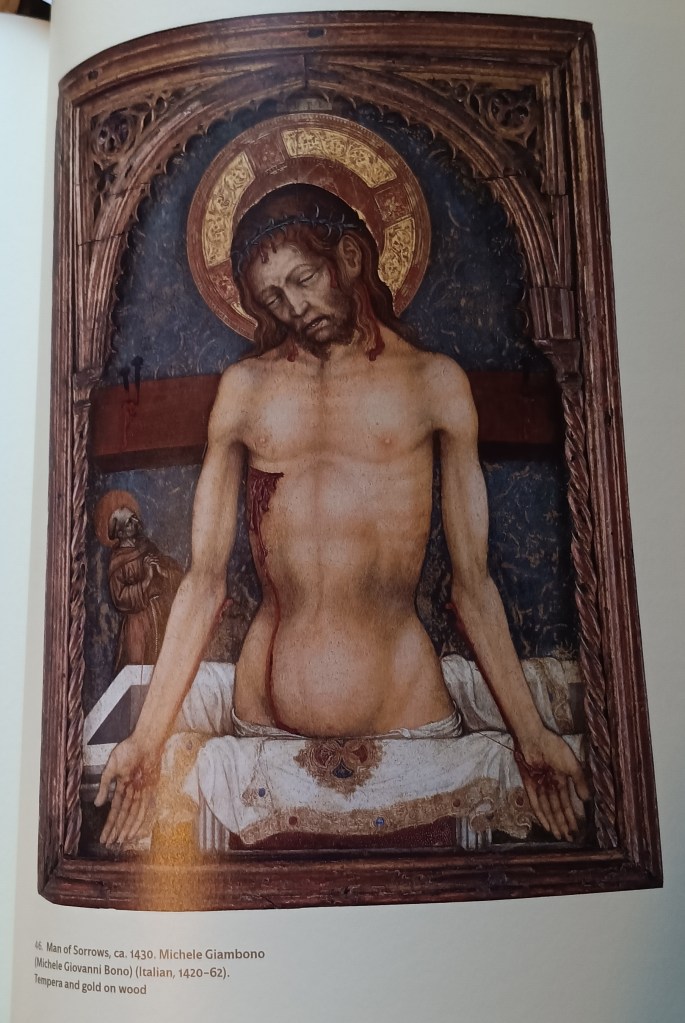

The book starts, therefore, with the ‘wound’, that phenomenon in which the skin is broken to form a hole through the inward being lives under the skin. But it argues that in the hands of medieval sculptors and painters no wound is merely a wound, especially when its special nature demands to be made apparent, such as in the representation of the wounds on and through Christ’s skin through the process snd duration of the Crucifixion. The meanings given tongue holy orifices, particularly the side wound made by the spear of a Roman soldier, proliferate and pay no account to the gendered associations of those meanings. The wound takes on the role of a portal to inner life and life’s springing forth, and therefore, it must also be a gate to the womb, a vulva.

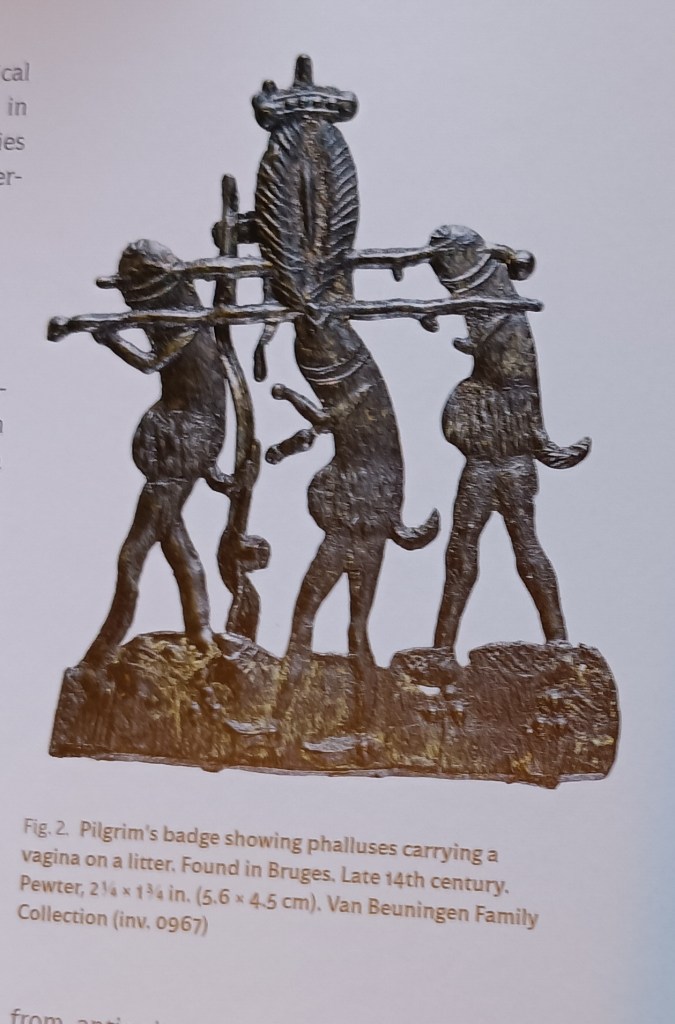

It used to be said that we are being Freudian when making sexualised interpretations of phenomena across over domains of life, but this book shows that Freud is not needed to see that sexual and religious passion could not be separated in the medieval mind. This is not because they were considered the same but that both mattered in the same way, as knowledge of the incarnated spirit’s potential for experience. As a wound and a vaginal orifice, the phenomenon pictured above with its dark interior, invites penetration, and thus, holy men interpreted it. Satirists or explicators of holy symbolism (we do not know which were implicated in the example below, a pilgrim’s badge), could even make its role as a vagina obvious by having it attended upon in a procession of religious pilgrims by a troop of stiff and bushy-tailed penises.

This imagery is transgendered, undeniably so. So are its consequences in representation of the love of Christ , where holy men and veiled women may equally fondle the wounds, the monk rubbing his hands in both pleasure and pain on the and hips of Christ’s body on which his sacred blood drips.

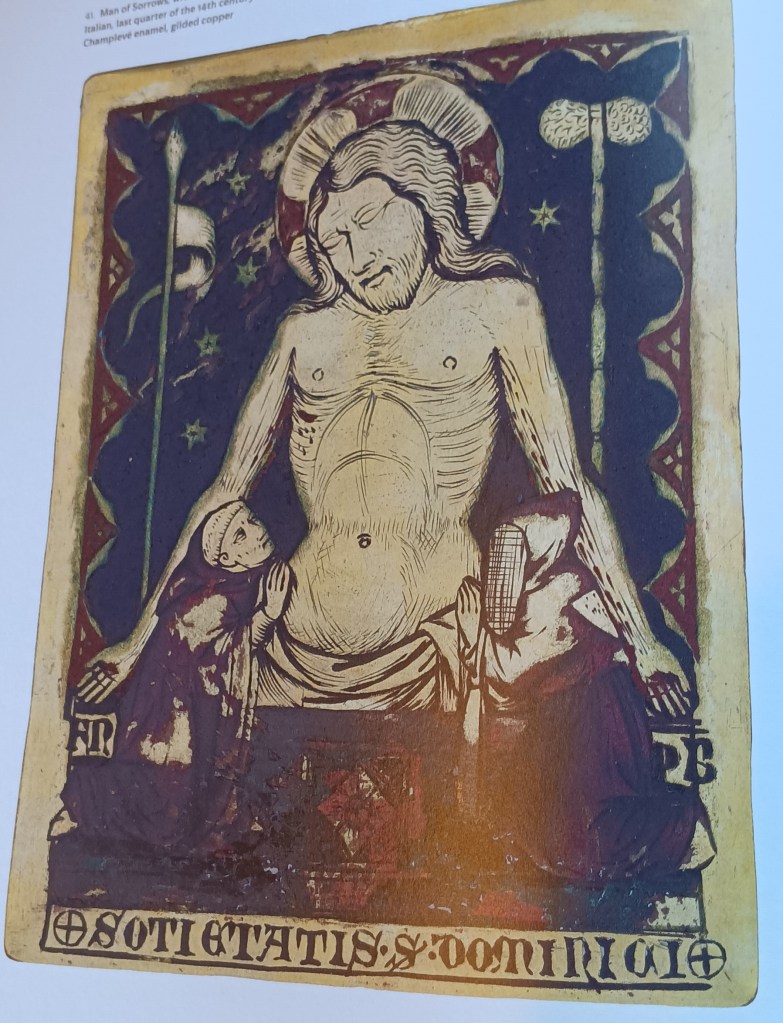

Of course, the religious contemporary will leap to say such bodily gestures and proximity are merely symbolic of brotherhood in the faith, or a love that can only be Platonic, but that does not explain why the body of God the Son is so often symbolically sexualised, a bejeweled emblem covering but also manifesting his groin area in tje following painting of the Resurrection from the Tomb, attended upon by St. Francis. The shaping of the lower body demands we expect the absent genitals, which are not only absentee but perhaps made androgynous by the crossed circle laying where those body parts would be seen had Christ risen further from his coffin, were the representation intended to be unambiguously biologically male:

And that body is viewed by desire,such as that of the Carthusian monk below (blessed by an angel of the Lord, whose gaze seems to travel up the legs of Christ and to merge with the floral decoration that blossoms in its direct path, but not to engage with His face. As the authors say the diaphanous underwear over the genital area of Christ’s body seems there more to point its near disappearance. They point to another Carthusian text in which a monk warns that that images of the naked Christ raise impure thoughts, noting:

how such images direct the eye to Christ’s loins in a way that tempts not only women, but also men, even those sworn to the monastic life. [2]

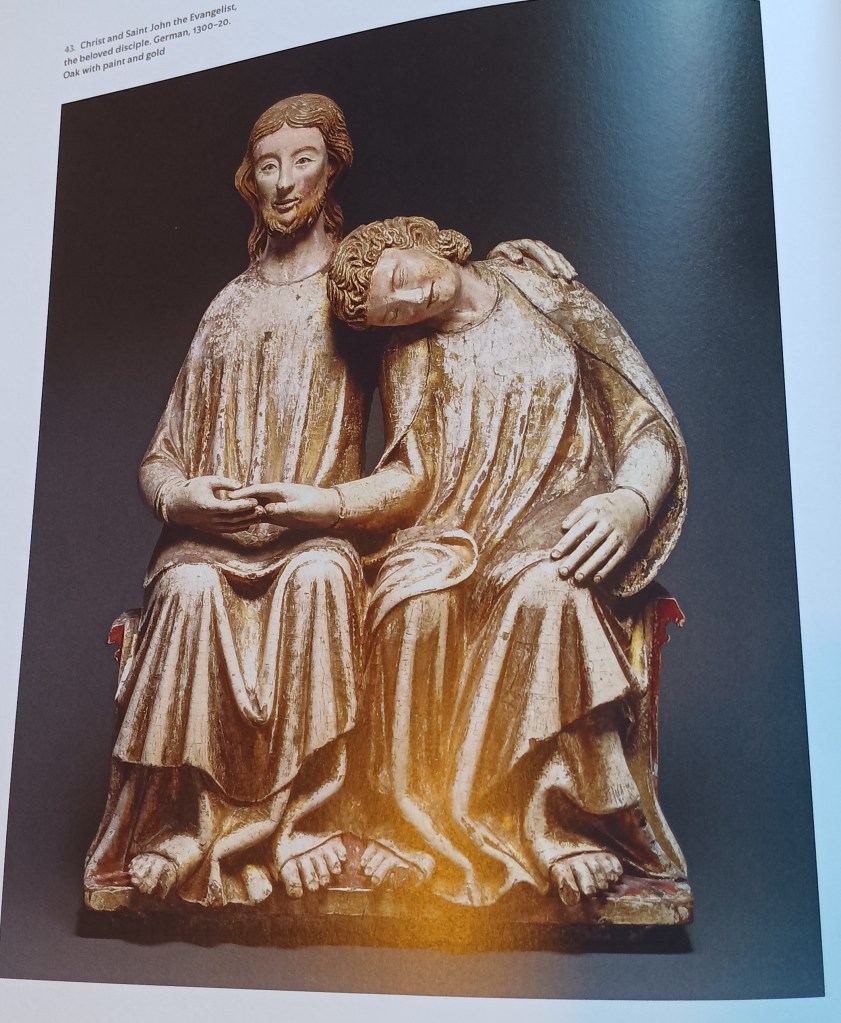

Likewise, the love of god once embodied must be shown by other kinds of affectionate bonds signified by closeness of bodies, as in the favoured representation of the evangelist John laying his head on the breast of Christ, supported by the Lord’s hands:

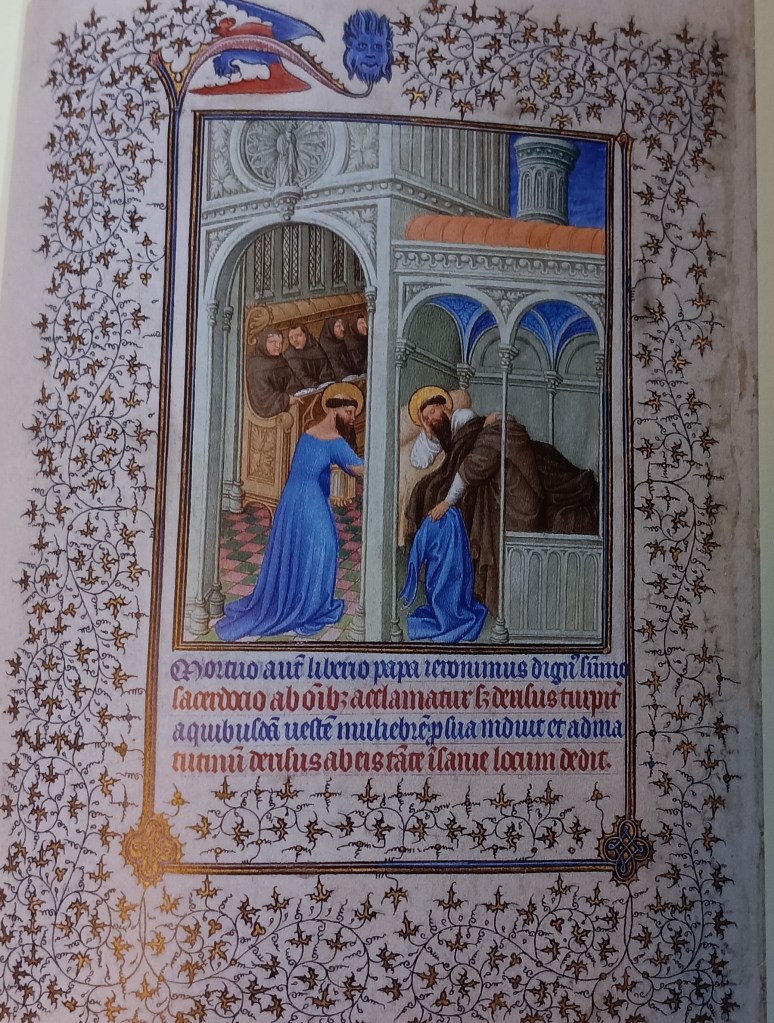

Divine love clearly admits of love within one sex/gender of supposedly defined binary creating division into two, and only two. It is this perhaps that explains artistic interest in stories of transgendered sainthood are to be expected, though difficult to read in terms our times or those of medieval people. Below is an illustration of the story of St. Jerome, in which an errant monk places a blue undergarment for a woman in the Saint’s chamber such that he will appear to have slept with a woman when he mistakenly dons it instead of his monkish robes for Matins (the timing of events moves from right to left). Whatever the moral of the story – Jerome leaves monastic life as a result of the incident, the artist is clearly more interested in the brothers’ prurient gossip about him when they see them in feminine blue. There is a pride in Jerome as well as anger in how he is represented that thrust the holy brothers into the category of the unholy whilst their trans appearance marks his sainthood. Clovis Maillet argues that:

Gender was more fluid in early Christendom, when abstinence was a more important distinction than gender, the boundaries of which were not firm. [3]

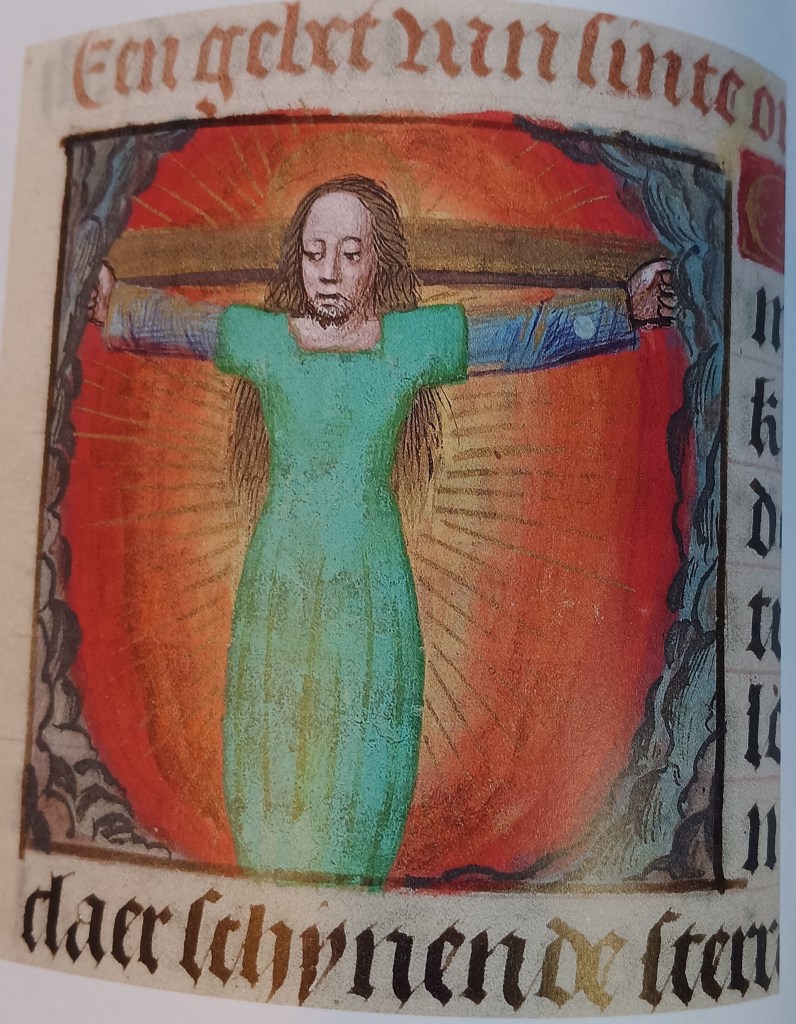

However, the transgender symbolism goes even deeper, even to identification with Christ’s passion, in the story of Saint Wilgefortis, who is painted hovering over Christ’s side-wound and vulva with a beard and dress, a phenomenon even more interestingly explored in the story of Saint Marinos. In both cases though justified by the bias to male appearance as the more spiritual in the society. The wish to cross gender comes from within and ‘invites the creation of community across time with those who identify as transgender and/or nonbinary today’. [4]

Moreover, we shall see that there are associations too with courtly love as readers of Gawain and the Green Knight have long known (see my blog on that poem here) that posits the possibility of the Green Knight to have sex in bed with Lord Bertilak. Because of the bias to male form in positive and active allegoric figures, Love for the French courtly lover is male (Amors) when the lover, though unnamed and only given the name Amant by commentators) is male. Their love is gender-queered because love is androgynous but looks like a male. The artist’s play here though is incredible: [5]

Much more like the situation in Gawain is the story in French Arthurian Romance narratives of Lancelot’s love for Guinevere, mediated by Galehot (sic.). In the French text, Galehot adores Launcelot in the same way as a knight loves his courtly lover, and in one scene, they show their love by sharing a bed. The medieval artist portraying the first kiss between Launcelot and Guinevere over the open lap of Galehot, also shows how desire has elongated the bodies of the male and female lovers but has not neglected also to show the loving foot play between Launcelot and Galehot, whilst the latter’s foot is somewhat distanced from Guinevere. [6]

One of the most intriguing features of the art is that it is at its most playful at its most exhortatory and moral – perhaps a feature of Medieval Mystery plays too. What of this beautiful work that illustrates acroos the upper and lower register of its illustration respectively, the Fall of Man and the consequence in ‘sinful love’ – the very wide concept of ‘Sodomia’ (much discoursed upon in the book). The artist, however, has shown more interest in his two pairs of male lovers than the prompting devils that surround them. The artist goes to lengths to show the pleasure of his same-sex/gender lovers.

Another instance has two men grasping at each others’ hand below a heart shaped lock in a money box. Morality about the love of money over other things it may be but we are more interested in these lovers than in their morality – why, after all, use it as decoration for a money-box.

The example below is the base of a plinth which would once have had the Virgin Mary upon it, her feet thus repressing and grinding down the serpent motifs in the base, as in the medieval iconographic association of Mary and Eve (some think Lilith is also there). But the association of Eve as she circles to meet the serpent-face at the other side of the Tree of Knowledge is that sin is again represented playfully as sodomia (the name did not apply only to men), even down to the playful masking of two apples in Eve’s other hand as her breasts being shown back to tempt the female serpent.

The Cranach illustration below has a similar intent. The serpent is close to Eve and blocks her from Adam. The chastising Angel does not get a look in.

But I was stunned by the small contribution of Karl Whittington on Saint Sebastian, where the artist is shown varying the take on Sebastian from a beauteous youthful frontal take and a disturbingly aged and fractured back. Whiirington argues that the artist varied his own perspective as a worker on the body of Christ. Whereas the frontal aspect is more finished, the sculptor’ final touches caressing, in the back we see him enacting the torturer, as spiritual exercises exported the faithful to imagine. Read this for yourself.

Do read this whole book. It is beautiful.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

______________________________________

[1] Melanie Holcomb & Nancy Thebaut (2025: 23 – 25) Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, And Gender in The Middle Ages New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art & Yale University Press’. In the books primary chapters I have not identified the chapter-specific authorship.

[2] ibid: 20

[3] Clovis Maillet (2025: 117) ‘Masculinities and Transgender Expression …’ in ibid: 114 – 117.

[4] ibid: 36

[5] ibid: 91

[6] ibid: 17 – 19

[7] ibid: