‘… stood kind of hyper’ and ‘itching for some … some fucking … ‘action.’ You know. “Drama”’. Another play to see and to make Geoff think his birthday present to me takes me and him back to Nottingham. The line here is supposedly said on ‘Trent Bridge’!

Clearly I have added to my birthday treats. Here is the new schedule:

| Tuesday 21st October | Wednesday 22nd October |

| 10.30 a.m. Lee Miller’s Surrealist Photography at Tate Britain, Millbank: Followed by river boat to | 10.30 a.m. Gilbert and George retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, Southbank |

| 2.00 p.m. Theatre Picasso at Tate Modern | 2.30 p.m. The Bacchae A new play by Nima Taleghani after Euripides, The National Theatre. 7.30 p.m. Punch Play by James Graham, Apollo Theatre |

To tell you why I needed to add this play to my birthday treat of events in London bought for me by Geoff, I have to tell you about the play as I read it recently, for I thought it a play that might bring both pleasure and fractured nostalgic reflection to both of us. Near the opening of the play Punch, in its ‘Prologue’, we first meet the protagonist, Jacob, a working class kid brought up on the Meadows Council Estate. He is standing on Trent Bridge because it is a good place to be bumped into by the hated cricket fans who go past the crowd you are with, who are ready for the football game on the other side of the road (as you see the grounds are parted by the road that crosses Trent Bridge over the River Trent).

Jacob says to one such who bumps into his mate Raf and refuses a friendly rebuke: ‘massive bridge not wide enough for you, is it? Think you’re like entitled to the whole thing, do yer mate?’ Even better, when you desire to feel that you are standing up to the entitled is when you see people from West Bridgeford perhaps, for one of the banes of his single working-class mother’s life, ‘Aspirational Working Class’ as she is those relatives who make her feel a need ‘to keep with the Joneses of Uncle John and Aunt Julia who lived over in West Bridgeford’. When he says this in the play, the company playing his working-class mates ‘give a fancy-pants “Ooooh”. In a mocking, la-di-dah way’.

Now Geoff lived most of his boyhood and young man status in West Bridgeford, whilst I lived in a council estate a bit more like where Jacob was brought up but not at a time when working class lives had been blighted by Thatcherism and drugs, usually in that order. Class then was always a part of our self-reflection: me from an aspirational working class family and Geoff definitively bourgeois, though his parents were first generation middle-class.

Having said this neither of us are young enough to compare with the kind of pressures – family and peer that Jacob experienced, for us, the fun will be the thrill of nostalgic reflection the play prompts for its naming of Nottingham sites and myths of interaction between its sub-communities, for me delight in seeing yet another James Graham play expertly done (I saw the great and very different play Make It Happen in Edinburgh this year – see my blog on it at this link). It is likely that the action of the play will age us in fact for our age is a commonality if class varies in nuanced ways. Nevertheless we enjoy good drama. But perhaps ‘drama’ never meant to us, at the age of the young Jacob, actually based on the real man Joe Dunn, and his memoir of his time during the establishment of restorative justice models in reactions to crime in English penal practice, what it does to the ‘youth’ of this drama.

The line supposedly said on ‘Trent Bridge’ is this (without the omissions in my title)

I’m not like proper ‘buzzing’ yet ‘cause it’s only the middle of the day, but I’m stood kind of hyper on Trent Bridge, itching for some … some fucking … ‘action.’ You know.

“Drama”’.

On the middle of things (‘in media res’ in terms of narrative) but here represented by the ‘middle of both a real bridge and real day, that middle seems sort of special – sunny, free – except ‘there’s an edge’. Being in the middle but yet on the ‘edge of things may be what this play is about. I am just so excited to see it.

That edge is similar to the ‘buzz’ or ‘kind of hyper’ the play boasts but it is not only analogous to but partly caused by stimulant drugs – a ‘line of coke’ and it feels like both being in and ready for ‘drama’ as well being ‘present’ in the living moment. Much of this was alien to my generation and perhaps Geoff – we have never talked about it. My drug was alcohol and I remember its depressant effects best. But what I do remember is the class antagonism to the people we saw who appeared to want to be (and demonstrate – whether they did or not) they were superior to you. At a party, drugs help you ape that class leap into self-confidence – mainly alcohol did for me. Jacob expresses it thus, as he drinks his first champagne and they:

Started popping and pouring, so I’m like (poncing around) ‘lah-di-dah’, whoow, look at this, lord of the manor. Look at us.

Look at us …

From the ache of being seen as superior comes the one means of showing it in some forms of groupings – not necessarily entirely masculine now – the fight.

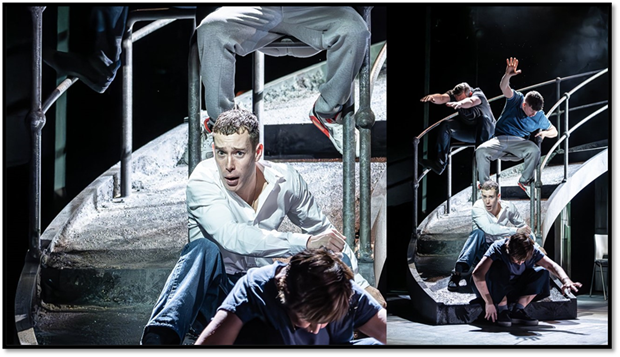

And these stills show some further parts of the reasoning that see violence as social-environmental in cause. What Jacob finds is that the more belligerent he is, the more the ‘lads from the Meadows, like me’, the more he is washed off the conscience of the establishment with an ‘autism’ diagnosis and the more he is sucked into the interiors of the social environment – like that replica of an underpass above. The Meadows is a kind of fantasy through which the established order play out and create the futures of working class kids in the mass an deprived of satisfactions otherwise. That isn’t just done by drugs but by technology:

Jacob The Meadows has a shit ton of CCTV high up on lamp-posts to make ’em harder to knock down. But it became the stuff of urban legend that you can get from one side of the estate to the other on particular routes without being picked up once by the cameras.

Tony the ‘older gangster’ arriving to impress Jacob and Raf and co.

Tony You wanta go up Mundella on the east side, then duck behind the abandoned white van at the top, arcing round to the west side of the street and under the pass onto Beauvale spinning north over the fence between number 12 and 14, behind the bins toward Holgate –

Jacob It turns the Meadows into a sort of real life, multilevel video game. And me and the younger lads are determined to complete it.

Fromm CCTV technology to video-game hyped by stimulants to hide the seams, the estate itself is made to satisfy the needs of ownership and control otherwise denied the kids. And this makes for high ‘drama’ without the bourgeois need to visit the theatre – as old converts like us now do:

A ‘chase’ by Police through the Meadows that is maybe more dancelike.

Jacob That’s the thing about the Meadows, it’s ours, fucking OURS, you get me! You toss some stones at a passing police car and leg into the sanctuary, our haven; it takes them fucking five fucking minutes to speed round, ’cause there’s no roads in, but we’re gone in two seconds. Un-catchable. Impenetrable, mate. The Meadows. Our backs to the world.

Against the sounds of some British grime on the decks, Jacob runs, and freezes every time some ‘headlights’ hit him – spinning, turning, bending his way around the space.

He makes it to ‘safety’ . . . catching his breath . . .

Jacob . . . See cos this is the problem, no one likes to admit . . . Doing bad things . . . creates good feelings. It just does.

When Jacob says this he is in some sense out of time in the play: narrating the story to a therapy circle and to the parents, Joan and David, of the young man, James, whom Jacob’s one-punch killed, unintentionally but yet: ‘no one likes to admit . . . Doing bad things . . . creates good feelings. It just does.’

From these excerpts you will see why I am excited to see this play – even its more sober second half which explores the ‘restorative justice’ process through which Jacob comes to be accepted and assisted by the parents of James, the boy he ‘killed’, and whom he too helps. The play has to defuse. You can’t allows be in the ‘thrill’ od the ‘present’ – the drama’. But sober oldies like Geoff and me know that there is a quiet but equally tense drama in the contradictions of our feelings for vengeful punishment and restoration of a calm and loving forgiveness – though that last word needs a lot of nuance behind it. That we all need the buzz is admitted in Joan’s reflections of her son’s life where the buzz is contained in forms that he can, as a paramedic, afford to purchase. He too is ‘a sort of adrenaline junkie, … worried me sick, but made him feel so … ‘alive’. And I long to see Joan for she is played by the incredible Julie Desmondhaugh, an actor par excellence.

Derek, Jacob’s college professor, makes us realise how deeply structured into working class lives is the despair that robs them of James’ legitimate pathways to feeling ‘present’ and feeling ‘drama’ (as I say Geoff and I can just afford the theatre on our pensions) :

Professor Derek marches on with a force. ‘Military’ in his manner.

Derek Alright, listen up, you lot. This is not school, this is college, the law is not making you come here, I am not making you come here, you could turn around now and walk out and never see me again and I would lose zero sleep over it. You are here because you say you want to be here, or ‘profess’ to. Profess – verb – make a claim à la, a professor, i.e. ‘me’. Your professor, Derek, hello. (Hand out to . . .) ‘Derek’.

Jacob . . . Jacob.

He takes his hand – and shakes it. BAM – he spins back to us, back narrating to us, as new worlds emerge and pass by now.

Jacob I even got a fuckin’ job, and I managed to actually just about hold it down. Packing, shipping, at the Boots warehouse.

Derek (passing by, as Jacob ‘packs’) Logistics! The new, post-industrial legacy of Nottinghamshire. Mines? – gone! Quarries? – filled in. Factories? – shut. Lace – fucked! In its place – ‘emptiness’. Vast acreage of emptiness, warehouses, to store shit that gets shipped here, for us to hold it, and then ship it out, away, somewhere else. We used to make things. Now, we just move them about.

You’re the Meadows, right, Jacob? Arkwright Walk?!

To Derek, the story of Jacob’s rehabilitation is as flawed as the story of his decline through feelings of being wasted by a society that sees him as redundant to its purposes. The capitalist economy will use him for a while. Knowing who Arkwright was, there is an Arkwright Street in The Meadows, is also knowing the industrial system that places Jacob as it does. But here’s a play that shows us that we have to do something to ‘survive’, whether or not it has an edge to it – which it appears only the young have the energy to pursue – damaged or dead in the process as they might be.

I cannot wait to see this play. Thank you Geoff, my darling husband! I will report back for clearly you can’t even imagine this play in performance by text alone.

With love

Steven. xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

2 thoughts on “‘… stood kind of hyper’ and ‘itching for some … some fucking … ‘action.’ You know. “Drama”’. Another play to see and to make Geoff think his birthday present to me takes me and him back to Nottingham. The line here is supposedly said on ‘Trent Bridge’!”