James VI & James I: Why curators undermine the case for a ‘homosexual‘ King James. Visiting the exhibition at the Scottish Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, on the 10th of August, 10 a.m.

On the 9th August my evening ending at 9.15 and I walked from the venue of the Book Festival (The Futures Institute of the University) to walk back to my hotel – on Rose Street – via The Mound. i was still thinking of where to go on the next day, for my morning was free. These photographs were taken in minutes of each other but the blue skies over Edinburgh Castle, and indeed over Waverley Station, had gloomed by the time I took the steps down past the Scottish National Gallery and Royal Academy, as perhaps you can see. Soon I would see the advertising for the Andy Goldsworthy retrospective at the Academy. I didn’t want that to bounce me into the decision – after all I used to think I adored Goldsworthy’s work but it has passed me by (was it me – I still haven’t decided) and, latterly, in my last personal library cull, I let my Andy Goldsworthy books go to make room for other art – indeed other sculpture, whose rationale and realisation mean more to me.

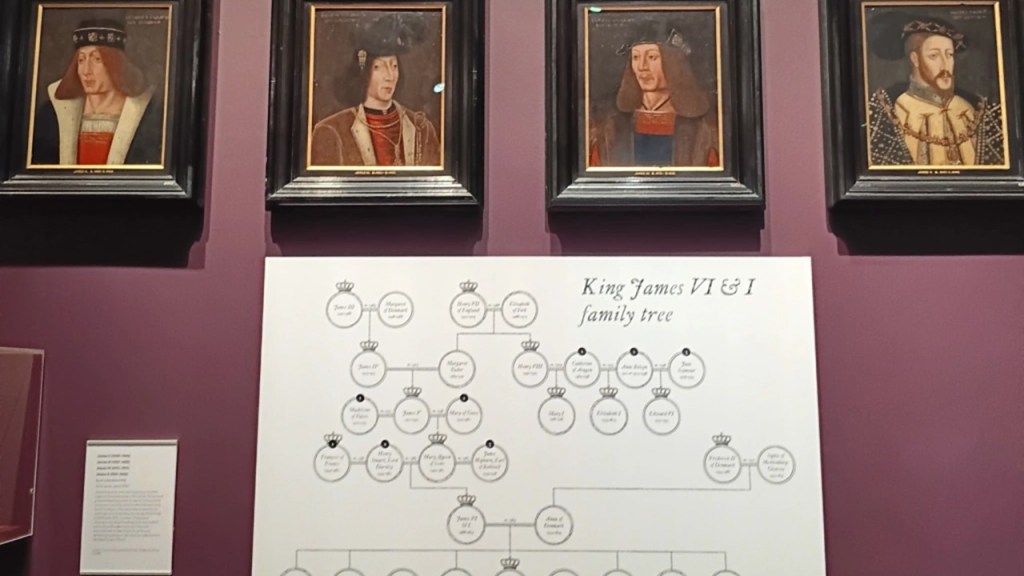

I knew I might reconsider tomorrow, but not as first thing. So i looked ahead and the rising of my eyes went with a memory of another exhibition I was toying with – on portraits of the person and entourage in a number of realms of James I of Scotland who was to become James VI of the Union of the old nations of England, Wales, Ireland and Scotland.

I am far from a Royalist and James is moreover harder to like than most monarchs – a man so sure he was ‘God’s Lieutenant on Earth – that he fostered the doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings that was to be the death of his second son, the coming Charles I. Moreover, the publicity I had seen for the show insisted that James was a neglected historical figure (an idea I find it difficult to agree with) – overshadowed they say by his mother (Mary, Queen of Scots) on the one hand and Charles I on the other. Maybe because both the bookend monarchs were beheaded at the behest of those some were to call regicides was the reason that publicity entertained. Whatever, it seems wrong-headed. James is a giant figure in my imagination – not least because Shakespeare best period as a playwright fell under that King’s patronage and is so heavily associated with the play Macbeth – the Scottish play. But also it was because James I was, since my schooling, a queer icon- his queer sexuality presented to me as a fact. And we are told in the opening web page material on the show by the National Galleries of Scotland that:

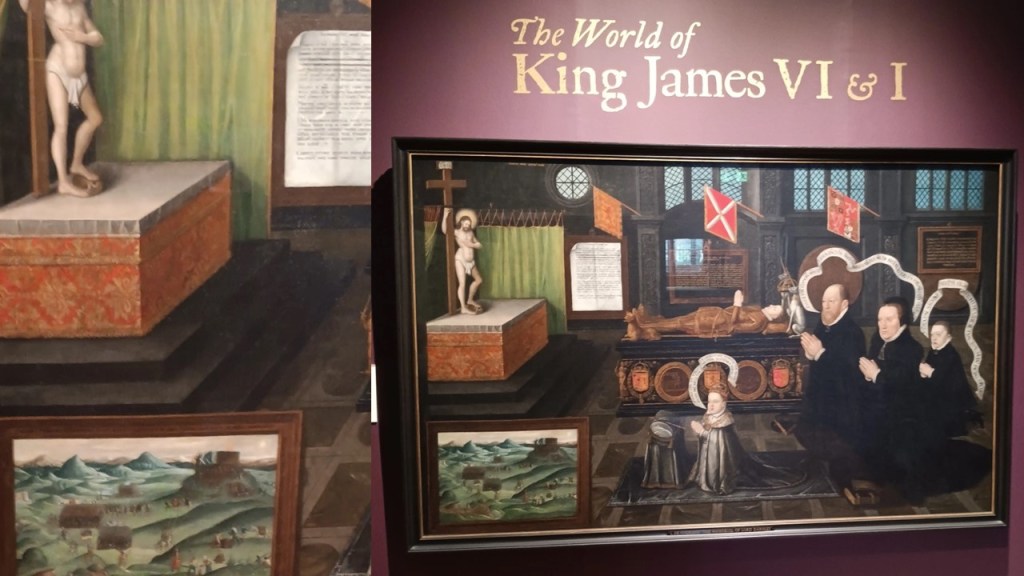

Drawing on themes with contemporary relevance including national identity, queer history, belief and spirituality, The World of King James VI & I is an enriching journey through the complex life of a king who changed the shape of the United Kingdom.

Who could not be moved. By the morning the sun was shining over St Andrews Square as I walked from Rose Street to Andrew Street and then down to the National Portrait Gallery, dwelling on what might be meant an ‘enriching journey’ thus resourced with themes and theory.

In fact it is probably not clear that queer theory was very much foregrounded – although it remained the point that James is not, and ought not, to be considered as ‘gay’ or ‘homosexual’ as the twentieth-century imagined these terms, but that his relationships and identity were specific in being queer – which registered the dispensation allowed kings to be different from all norms. Nevertheless much of the material that forms commentary on the exhibition still contests whether James had sex with the men who were his favourites. This despite, and perhaps because, modern TV representations of this King assume this sexual interest – like Sky TV’s Mary and George, about the most beautiful of the King’s favourites – George de Villiers – and his scheming mother who plans the relationship as a means for her own access to power. Most of that film is fantasy realised in pretty images:

Nicholas Galitzine as George and Tony Curran as King James in Mary and George Sky: from https://www.radiotimes.com/tv/drama/mary-george-true-story/

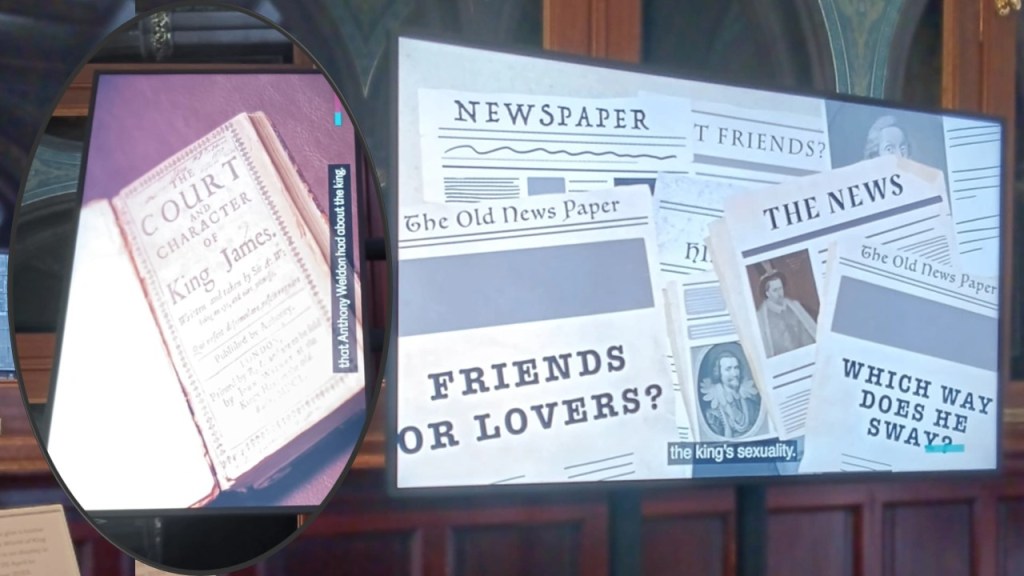

Moreover, queer theory can be evoked precisely to avoid the danger of imagining James or George in terms of a modern fay or ‘homosexual’ love affair. This is discussed in the two short films accompanying the exhibition and played in the Grand Central Hall next to it – you can actually see both though on the Galleries’ webpage (use the link here and scroll to each short film). The films make the point however that over-powerful subjects – lords of the realm and / or courtiers – often use the accusation of lustful sodomy to besmirch the reputation of kings, and that may have been the purpose of the frustrated and rejected courtier Anthony Weldon in writing his virtual satire of James in his The Court and Character of King James. They liken it to something like ‘fake news’ exposing not the nature of the King’s sexuality but the looseness of his ethics – with men and women. It is not likely that the seventeenth century would ask ‘Which Way Does He Sway?’ but to assume that he would be turned by any opportune beauty, regardless of sex. And queer is a better term here because the binary gay or straight, homosexual or heterosexual, just did not exist – this is the extent I think of the queer theory used.

But if queerness was a means of allowing the King sexual dalliance with favourites, it is the power and status of such ‘favourites’ that really upset the nobility, especially when the favourites derived from the lower classes. Attraction of the king’s sexual desire they could feel in some way, gave some men – not possessed of privileged access by birth or wealth or both (though both were possessed by some favourites) – an unfair advantage. That is certainly the feeling of the nobles about the lower class Piers Gaveston in Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II (full text at this link).

EARL OF LANCASTER: .......

Thus, arm in arm, the king and he doth march:

Nay, more, the guard upon his lordship waits,

And all the court begins to flatter him.

EARL OF WARWICK

Thus leaning on the shoulder of the king,

He nods, and scorns, and smiles at those that pass.

THE ELDER EARL MORTIMER

Doth no man take exceptions at the slave?

EARL OF LANCASTER

All stomach him, but none dare speak a word.

YOUNG MORTIMER

Ah, that bewrays their baseness, Lancaster!

Were all the earls and barons of my mind,

We'd hale him from the bosom of the king,

And at the court-gate hang the peasant up,

Who, swoln with venom of ambitious pride,

Will be the ruin of the realm and us.

The duty of Kings was to produce offspring and sex had one of those uses. But no-one felt that sex was limited to the purpose of reproduction, except in sermons, and Rona Munro’s 2016 James Plays (about the first three royal James Stewarts (Stuarts as the English would later enforce it)) give a strong fictional flavour of wide-ranging sexual expression in the family. The Stewarts were a strong tree but full of various fruit, not all reproductive assets.

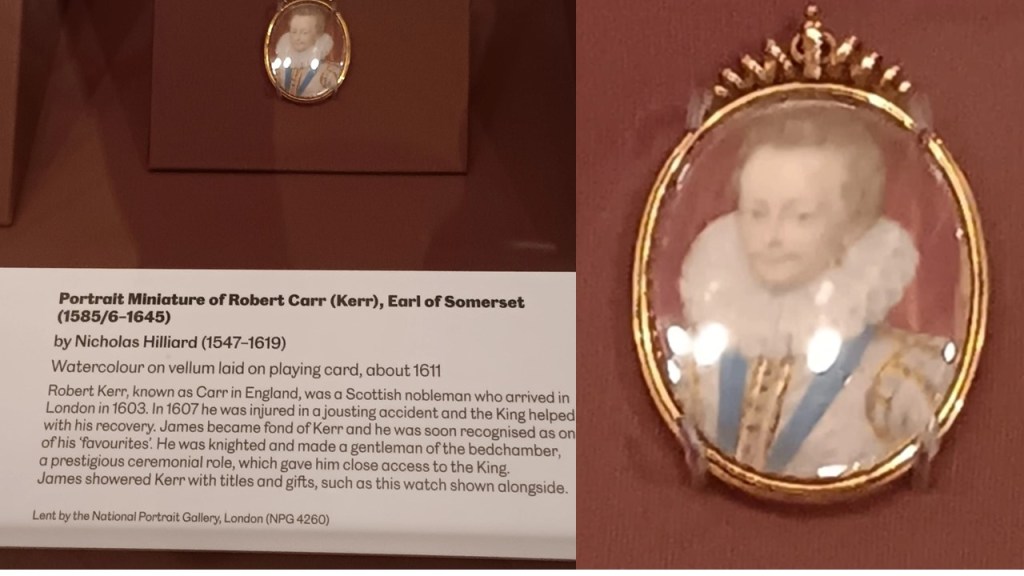

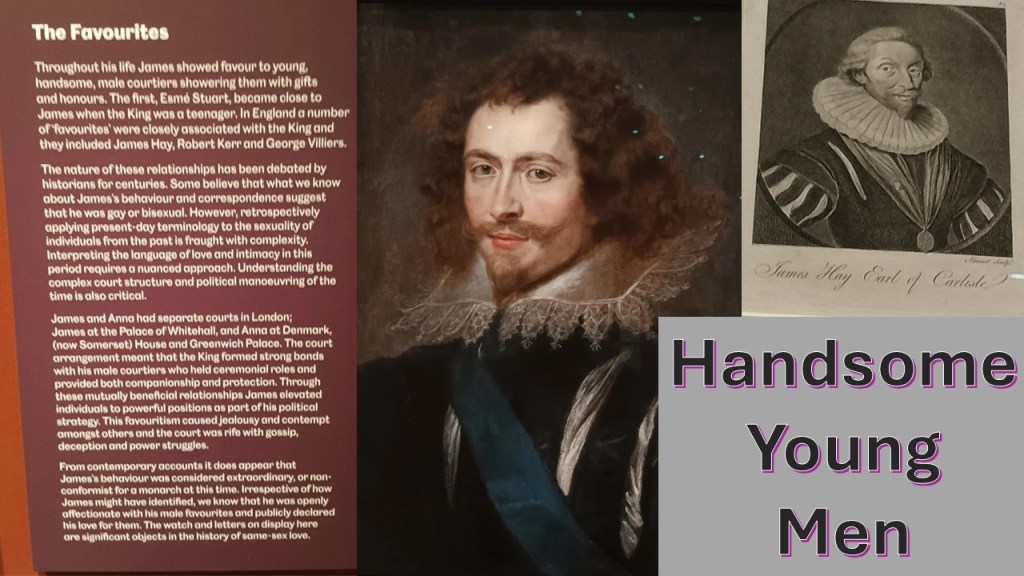

The favourites get represented, including Nicholas Hilliard’s beautiful miniature of Thomas Kerr [Englished as Carr]’ gorgeous in his self-evident youth and dressed to match the value of a King’s love of him. So much historians sweat has gone into de-queering the relationship of King’s and favourites, people forget that sexual, and even romantic attraction does not necessarily happen in order to acquire a label and coexisted with other relationships that often had very different meaning for their participants.

That James liked handsomeness in his favoured male courtiers could have been a question of ornament, akin to James’s love of very shiny and blatantly costly jewellery. But we are still taken aback by the beauty of George de Viliers (centre in the collage below) if not by the representation of the earlier favourite Hay (top right).

The explanatory text on the favourites (left on the collage above) is careful and correctly cautious about terms, but it locates James overt need to go beyond the usual decorum norms in speaking and acting affectionately with men, so much so that the queening of norms us the best model of describing it.

In many ways, however, even if contemporaries found James over the top. or feigned to do so in Sheldon’s case, the norms themselves are not ones we should assume as at all recognisable in our day. We watch Lear’s relationship to his Fool in King Lear and forget that such relationships were time honoured and not just a match of entertaining the King and passing the time. The portrait of King James ‘fool’ Tom Derry is a jewellery this show, showing as the explanatory plaque says that the cost and show of his apparel showed him treated as if a ‘gentleman’ (that is a person of recognised social status) but also showing affectionate service to your lord being modelled. And Tom himself is no mean looking man.

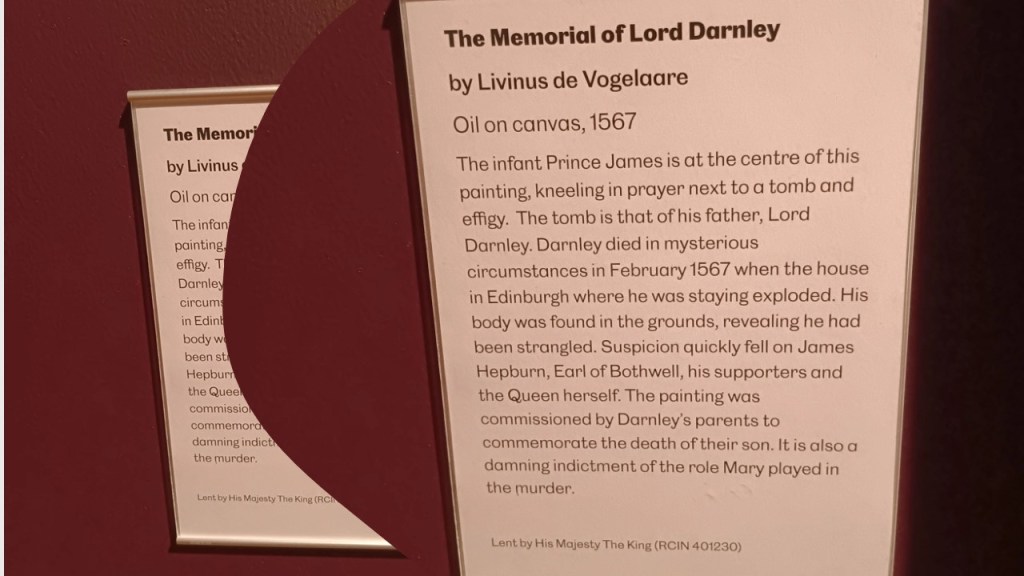

This is a world then where, if norms were transgressed, some distance from what ordinary norms are thought to be now must have been achieved. If anything is clear in this show, it is that behaviour was expected to be performative so that emotions were readable from afar. As you enter the exhibition, you see the wonderful masque-like theatre of ‘The Memorial of Lord Darnley’, James coutier father and the probable victim of a murder organised, or so Darnley ‘s family thought, by Queen Mary, Janes’ mother, to regularise her relationship with her next lover, the Earl of Boswell.

Yet nothing in the description prepares you for the extremity of the performative in the family’ commissioned psinting, pointing the finger of the father-deprived son painted there at his mother’s sexual perfidy. Here, then, it is, with all its coded meanings made apparent, even to designing in the the landscape of the murder of his father propped into the corner of the picture level of the allegory. The Darnley allegory is meant to show Mary that James is his father’s son and will be the mother’s nemesis, which, in a way was the way events transpired, helped on by Elizabeth I’s association of Mary with Roman Catholic plotting. From the beginning James performs a part prescripted for him, though he twisted and turned out of its showy conformity into his own.

This boy, born in Stirling Castle, was brought up to perform, even as a child (a concept not clearly meaningful in this period) as a man, when not representing issues of Succession and proper religion, he was already the courtier in training – telling hand on hip and gamer in the open countryside, with his hawk there telling the child what kind of man he must be.

Even as a boy, he is represented in a manner counter to the signs of Baroque European Catholicism allowed in portraits of his mother, his ginger hair already the darling of people who represented him (as in James Cyurran’s version in Mary and George)

The early portraits show a man keen to be looked at, and emphasised his non-binary beauty, even if the gestures had to be manly – hand on the hilt of a sword. Though increasingly James went from the black associated with the perpetual widowhood of his mother to bejewelled and dressy show

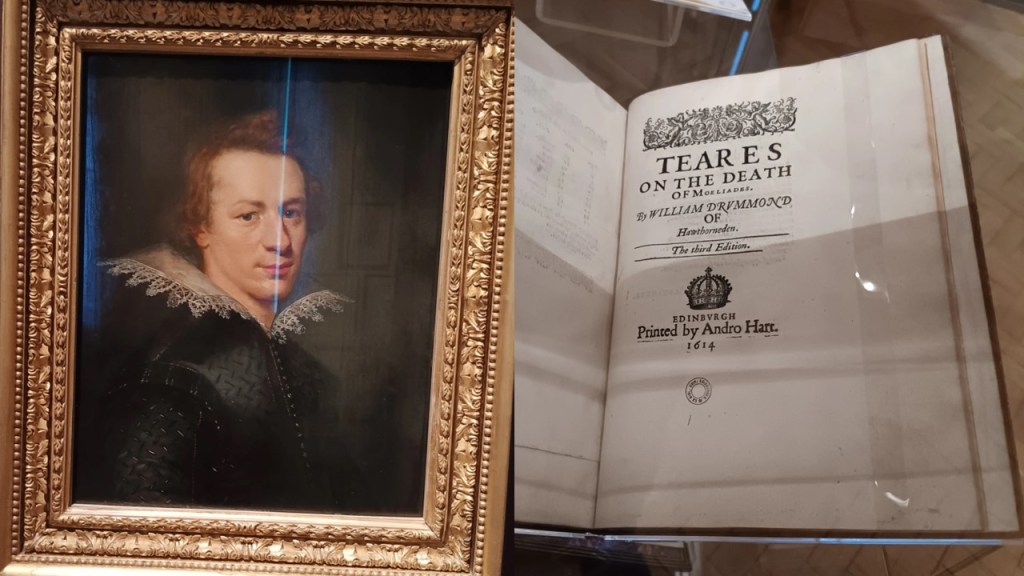

But this performative was not unusual to James as a Baroque monarch, even if the need to manifest his Protestantism often reigned him in. The norms of the English Church he inherited were increasingly those of a ‘true’ Catholic universalism, a return to the Imperial orthodoxy of the Eastern Church was how Elizabeth I often represented it, and monarchs acted out allegories of beauty meant to be heavenly. This was the case on the death of his first son, Henry, Prince of Wales, about whom many poems were written that emphasised his virginal divinity. The only one represented in the exhibition from the many made is a beautiful first edition by William Drummond of Hawthornden, a Scottish laird-courtier, who joined James in England on the Union of the Crowns. The book is described thus in his Wikipedia entry:

Drummond’s first publication appeared in 1613, an elegy on the death of Henry, Prince of Wales, called Teares on the Death of Meliades (Moeliades, 3rd edit. 1614).

The boy honoured is described as in love with Christ’s body. It is not clear in the porm that Henry is not the very reflection of Christ in a mirror or a deep pond of water: for both could be:

Narcyssus of himselfe, himselfe the Well,

Louer, and Beautie that doth all excell.

Here is a taste of the source of those lines at the end of this poem which becomes so deliciously autoerotic that we almost forget two male bodies commingle here – Christ and Henry, and the burden of the poem is a conceit of turning away from sexual women to the body of Christ; ‘Moeliades sweet courtly Nymphes deplore’

Rest blessed Spirit, rest saciat with the Sight

Of Him whose Beames (though dazeling) do delight,

Life of all liues, Cause of each other cause,

The Spheare and Center where the Mind doth pause:

Narcyssus of himselfe, himselfe the Well,

Louer, and Beautie that doth all excell.

Rest happie Ghost, and wonder in that Glasse,

Where seene is all that shall be, is, or was,

While shall be, is, or was, doe passe away,

And nothing be, but an Eternall Day.

For euer rest, thy Praise Fame may enroule,

In golden Annales, while about the Pole,

The slow Boötes turnes, or Sunne doth ryse

With scarlet Scarfe to cheare the mourning Skies.

The Virgins to thy Tombe may Garlands beare

Of Flowres, and with each Flowre let fall a Teare.

Moeliades sweet courtly Nymphes deplore

From Thule to Hydaspes pearlie Shore.

Of course, the point is that in eternity, we are all satiated (‘saciat’) with Christ’s body alone. Hence the nonsense of seeing this as ‘homosexual’, as if it labelled a person, but which certainly is the queer that lies beneath the surface of norms, including the heteronormative.

And everything about James shows that he, like his son here, found an affinity of himself with Christ’s body. As the Head of the Church, he was indeed not only that but the Body of it, and I have no doubt that he took it seriously. If we think the book that tells us most of Janes is Sheldon’s attempt to make him look ridiculous, we have to remember too that he was a scholar amongst scholars and his role in the commissioning of what we call the King James version of the Holy Bible was extensive. And his book on Demonologie (sic.) manifests that he thought himself aware that he embodied the principle of good against evil, a belief that created a run of the burning of ‘witches’ in the name of God and King.

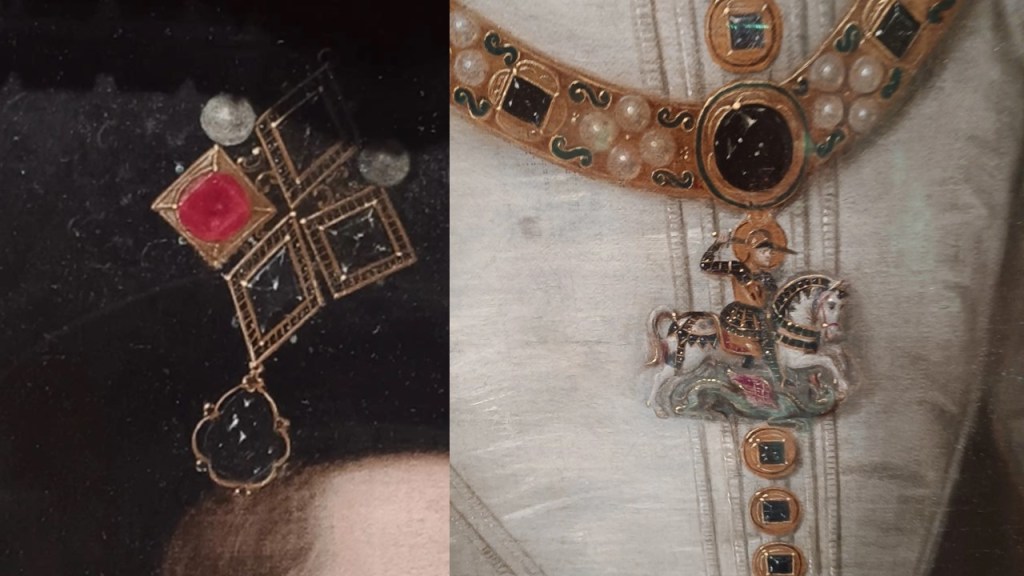

And then, the exhibition is keen to share, there is the love of costly symbolic jewels, that bore messages of his role much as they did for Spanish Hapsburg monarchs of the period. Everything bears a message. It types him like the wonderful chain in which he represents the Holy Knight St. George.

In portraits and in life, he saw himself as the cusp of a New World, a Union of opposites. For instance, that beautiful half portrait in the centre above may draw us that questing hy Knight, but it is in the name of Union. The jewellery ensemble in his headway symbised that Union, and was costly beyond other known examples of the time:

How to represent the Union became a feature from James’ accession and its completion under Queen Anne, the last Stuart. The exhibition shows some of the early designs for a Union Flag. They strike one as more beautiful than what we got, but perhaps ghey too might have looked brash by now.

This is a good exhibition, worth the seeing. After I left I felt good, headed for coffee somewhere and wondered – perhaps I ought to give myself a chance of liking Andy Goldsworthy. That is for another blog.

Bye for now

Love Steven xxxxxxx

One thought on “James VI & James I: Why curators undermine the case for a ‘homosexual’ King James. Visiting the exhibition at the Scottish Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, on the 10th of August, 10 a.m.”