This is my response to seeing in the flesha play in which I had shown some curiosity in an earlier blog; (https://livesteven.com/2025/08/01/being-curious-about-questions-you-never-thought-youd-ask-a-way-of-preparing-to-see-a-new-play-seeing-james-grahams-make-it-happen-at-the-festival-theatre-edinburgh-on-the-9-august-202/ ).

Of course, Brian Cox received the warmth of the audience in this play, and it was well deserved. What I had not realised was, that in the play, he first appears as himself, as a famous actor slumming it in a neoliberal morality play commissioned or imagined as so, for this surely never really happened, by Fred Goodwin as Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of The Royal Bank of Scotland and honouring the achievement of devolution and the opening of a Scottish parliament – a well-know star bussed in to attract interest to a play mainly made work by an exemplary cast of much less known actors. This ironic take was entirely intended. Was this what this play was doing, though? Was it using the reputation of Cox to enlarge the appeal of a play that would have been a great experience even without him? In the mock play, Cox mouths the lines quoted from Adam Smith lazily and without meaning them. His heart wasn’t meant to be even in the role in this play-within-a-play. Asked by Fred, how the ‘acting was going’, the actor playing himself snorts snd swears: ‘How do you think the acting is going – I’m fucking doing this, aren’t I?’

Is it a daring thing to suggest that the most famous living actor of working class origin in Scotland is doing a play about Scotland in Scotland and not yet a major TV US funded TV series, like Success, in the fictional time-space of this historical.satire-tragedy? It certainly works. I had not quite realised how much this play was meant to be a ‘Scottish play’ in which, like Macbeth in the play most usually called the Scottish play, Scottish heroes are weighed in the balance and exposed to salvation and damnation on the basis of examining whether there can be a ‘moral’ form of something based on rapine, capitalist economic growth, that would be working for all people and not just the few, as Adam Smith predicted there could.

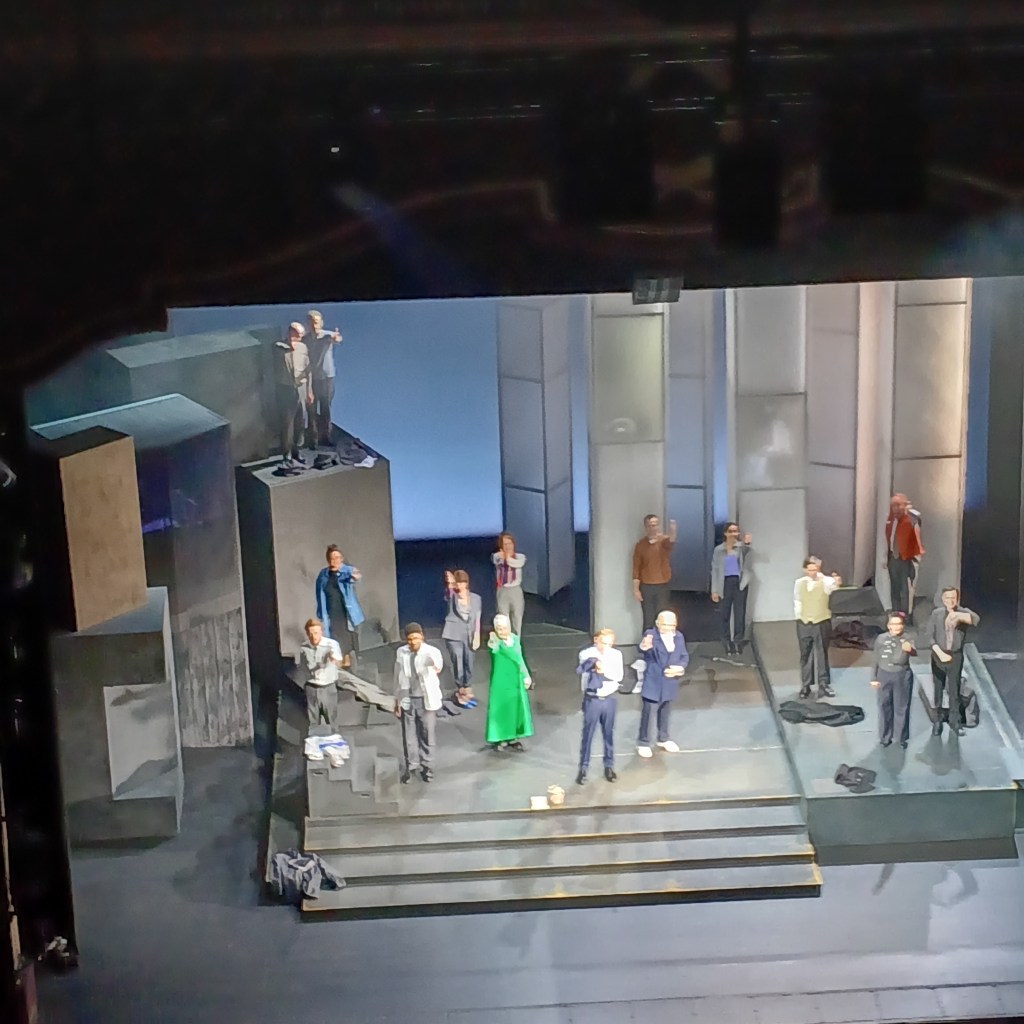

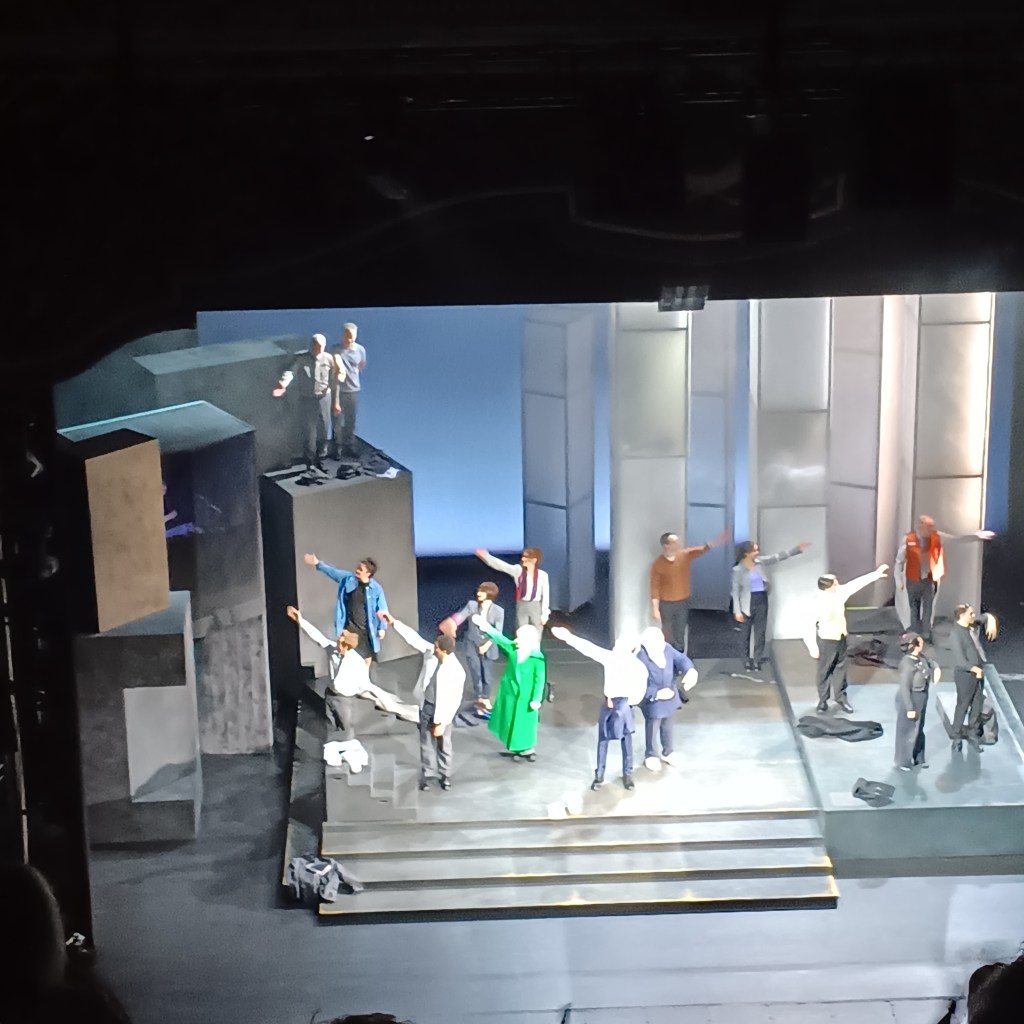

When, at the curtain call, the splendid cast ensemble paid tribute to the audience; it was to a Scottish audience, despite the reality of the fact that a goodly section of Edinburgh Festival audiences aren’t Scottish. The play is, however, determined to show that Scottishness matters, even in its sons made good in ranks of the hegemonically English UK. Among its sons is not just, for the time duration covered in the play’s main plot, Fred Goodwin but Gordon Brown and Alastair Darling, both richly satirised but also, in the end, exonerated (as misinformed not evil) because they mistook the show of capitalist self-glorification as truth and on trust, based on beliefs of the potential of endless growth, with ‘no more boom and bust’, as boasted by Gordon Brown.

These boasts are quoted and owned by the actor playing Brown brilliantly, but he even better shows the later irascibility of Brown in the role of a Prime Minister who learns that capitalism tends to resist shaping by anyone, let alone Prime Ministers who have based their politics on the belief that only unregulated [or in truth less regulated] economic growth is the path to social justice for the many. The play’s Gordon Brown is seen to be shattered by learning that capitalism operates outside of any moral control in its self-interest and secretly where it deems it necessary to self-interest, though he is also portrayed as a moral and good man aiming at setting things as right as they can be. That isn’t quite so of the representation of Darling as somewhat the puppy of the establishment.

What the play asserts I think is that the belief that we can ‘make it happen’ is first of all things hubristic, in Prime Ministers, CEOs, and countless others who do the bidding of decision-makers. It opens with the audience looking at a great John Bellany painting of the artist on his death bed hovered over by strange figures (presumably a reference to the current City Art Gallery Exhibition) or looking at it being looked at by guided tourists. Suspended in front of this death portal painting are masks that are claimed to be those of a tragic chorus representing the Furies as Aeschylus imagined them in the Oresteia. The ‘tourists’ don these masks and become hissing seekers of vengeanace too. It is a hiss we hear often, reminding us that mortality is not kind nor nuanced. The play ends with an unsettling hiss from the wings from this remembered tragic chorus.

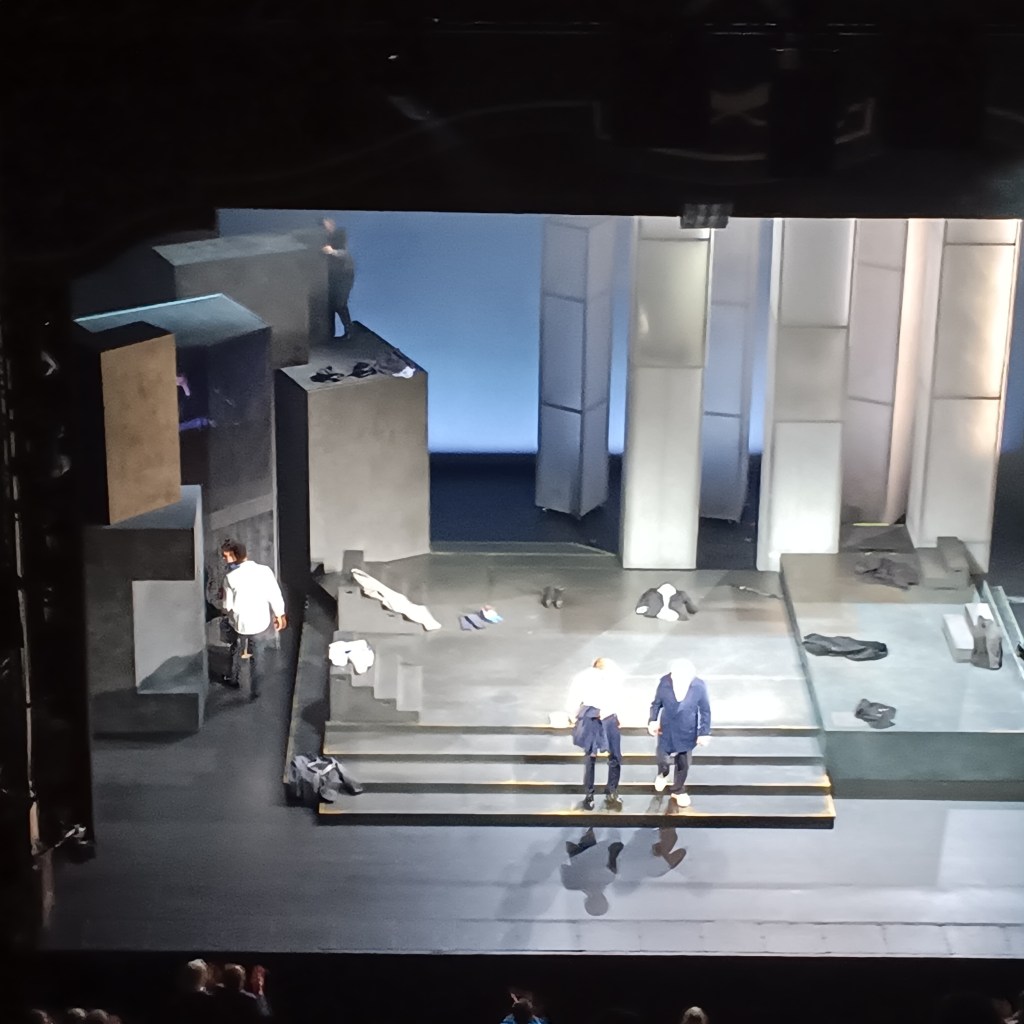

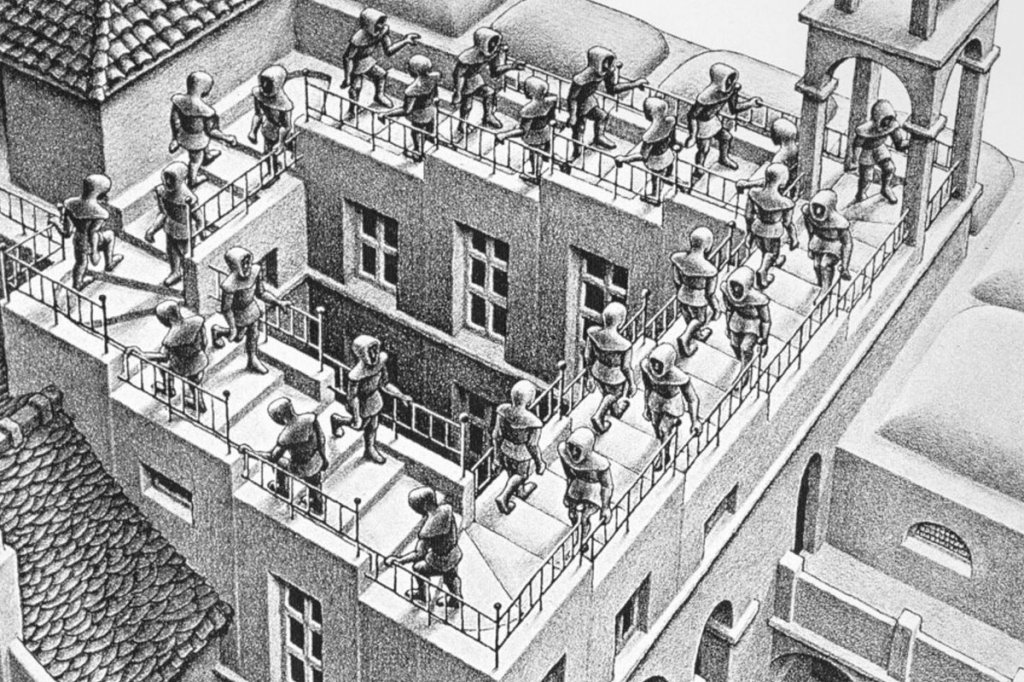

The drama operates too by the play of fine settings which in scene changes can evoke the hell of the Fingers Club where capitalists disported in karaoke, the grandeur of the unfinished dream of the Athens of the North, and by the placing of movable steps show the ups and downs of boom and bust and even careers in the surreal look of Escher’s version of the Penrose stair illusion.

The cast gave call outs to all that effective stagecraft

But let’s face it, Cox, though on the stage less than you’d think, makes a charming Adam Smith, and though often shown as an amalgam of the public images of both Smith and Cox – both commentators on the political absurdities of their times in private and public – the first more ‘sweary’ than the latter- what is said is rooted in a knowledge of the neglected text, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which probably gets quoted in this play as if it were ‘quite the page-turner’ Cox’s Adam Smith says it is.

None of that kind of stuff should work in a drama – we see it not work.in that play within the play within a play I mentioned earlier – but here it got a loving audience murmuring in agreement, applauding Smith’s moral summaries and wrapped in political goodwill, that even saved an ounce of empathy for Fred-the-Shred, despite his antipathy to ancient trees, the livelihoods of the many and his lovable queer PA, a real fine point in the production.

Fred still lives on half his agreed pension. Is that just? No. But neither is the world under Labour politicians still intent on seeing economic growth as the solution to questions it dare not even articulate and principles it no longer has. Seem familiar? Then you have already seen some part of this play. This was the last performance of it. It must be revived. I must read its text. Look out for it in either form.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

2 thoughts on “James Graham’s ‘Make It Happen’ at The Festival Theatre Edinburgh on the 9 August 2025, 2.30 p.m.”