There really was a theme to yesterday’s visit. In preparing myself for Lila Raicek’s My Master Builder, I re-read the Ibsen play as well as its contemporary re-imagining and blogged on it [see it at this link]. Preparation is a method not entirely universal for theatregoers, who often seem keen to see a story and characters unfold as if for the first time in front of them as an audience. Perhaps at its worst though, preparation is also pernicious for it exerts a kind of prior control over direct experience of what I see, feel, and inwardly re-enact inside the theatre itself and in the event of the play. Do I do it as a defence against the mastery exerted over my possible naivety by skilled enactors? That mastery is one that lies in control of spectacle, vicarious proxemics [or purposive patterning of bodies on stage in relation to each other], and the techniques of creating emotion and power from speech.

The manipulation of the seen and felt by theatre concerned Plato, and rightly so, though banning it from his ideal Republic is extreme, to say the least. To be honest, I think that for me, too, as a theatre-goer rather than political philosopher like Plato, preparation is a kind of attempt to defend myself from theatrical ‘magic’ – or as Iris Murdoch might have put it in her philosophical version of Shelley’s lyricism: a flight from the enchanter. Am I so concerned that some magus may take control in theatre – be it set designer, actor or director – that I embrace the text of plays beforehand and own some part of my direct response to it?

And after all, what attracted Raicek to Ibsen was clearly his ability to demonstrate that the co-construction of mastery and magical thinking in relationships made them very dangerous indeed – not only to the person influenced by mastery but the person invited to identify with being a master. If anyone, the victim of invented patriarchal models of dominance, and aspiration to it is Henry Solness in Raicek’s play, and Halvard Solness in Ibsen.

In each case, the supposed protagonist becomes the puppet of Hilde, the supposed underminer, in Raicek’s version, of the phallic fantasies that make men, envisaged as architects, spend their time making ever larger and more dominant erections for public show, or climbing them to the point of induced vertigo.

Yet stood outside Wyndhams theatre awaiting the arrival of my friend, Claire, on a sunny evening, already the Baroque lure of theatrical magic started to work. Only older theatres like Wyndhams from an age before mass entertainment became entirely constructed in spaces to which we need not even travel are capable of evoking in me this childlike wonder, even before a play starts.

From the start, theatre practices began to disrupt my expectations of text. In Raicek’s play, Henry is reconstructing a Sailor’s Chapel, originally erected in 1832 in The Hamptons, based on an even earlier one in Stockholm. The text asks for this to be constructed in some way and that it be ‘climbable’.

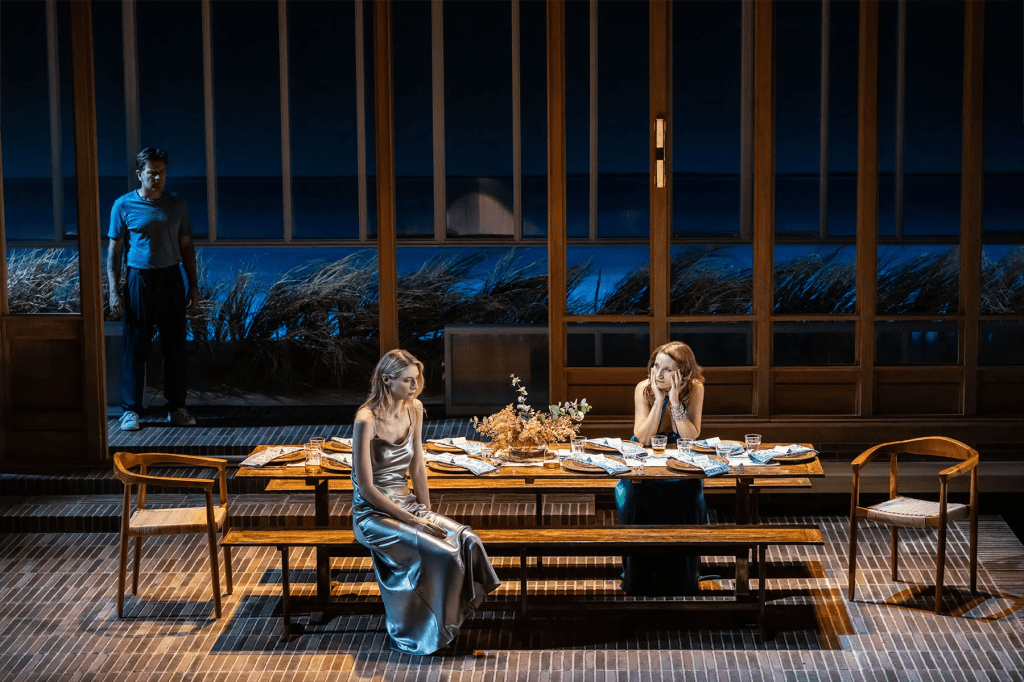

In this production, the basic structure was visible on the stage before the performance started. It was a huge structure with two transparent walls encasing a climbable structure, which was largely invisible. The changes to it could be performed by light alone, although I think the way the structure filled, totally or partially, the forestage and the proscenium arch varied. Only at the end does Henry ascend diagonally within the structure.

This was beautiful. It was in line with the way that climbing works as a metaphor in the play, as a kind of manipulative ascension for visual effect, or imagined visual effect, as in the case of social climbing or attainment of professional recogntion. But in a subtle way, it could be said to reference how mastery in acting is achieved too – through passages barely visible in their support of the rise to achieve for those both entitled to do it and willing to take risks.

For instsnce, many must have come to Wyndham’s Theatre to see Ewan McGregor as Henry Solness, and the effect of such stardom could be equated to something long practise at mastery built, although the process of building are lost in the mist of its apparently magical emergence, except perhaps for the actor who possibly remembers the early risk taking involved. Before the play, I tried to consider how it must feel to.understudy such a person playing such a classic role as Solness, for your appearance on stage, when that is necessary, must disappoint people who come to see a ‘star’ even before you even attempt to enact the role yourself. Interestingly enough, when Claire arrived at 6.30, we determined to go for a Chai Oat Latte, and on the way, Claire met a colleague from the same actor’s agency as hers.

This colleague of Claire turned out to be Richard Ede [Babble Voices https://share.google/jkjqZ60ufNFSR2GbD – agency photograph below], McGregor’s understudy in this play on his way to the backstage entrance for that night’s production. He wasn’t called on, and he is a very experienced actor, other than as supernumerary crowd cast as it turned out but the light this shed on true mastery was immense, though Richard showed no consciousness of this quality that shone in him through the modesty – being ready to step into a double role, playing not only a character but the actor enacting that character, who ‘ought, to have been there.

Such ‘mastery’ I can only imagine as an appalled and nervous readiness for a challenge that can not be gauged beforehand. Yet, this is possibly only another way of being, say, Elizabeth Debicki preparing to play Mathilde with all the famed Hildes of Ibsen behind her: Mai Zetterling, Maggie Smith, Joan Plowright, and so on. The role is difficult partly because Hilde must assert not only possession of ‘My Master Builder’, but sustain the role of a woman unable to become herself except as the imago of a man’s sexual fantasy, especially in this modern version where women set independent goals as workers or as lovers, even, as Hilde does, the role of sexual predator. My feeling is that Debicki does not quite pull off the interplay of all these roles, but perhaps no one could.

Kate Fleetwood, however, as Elena Solness is a different matter. Where Debicki cannot quite stop Hilde seemong a ‘victim’, Fleetwood as Elena explores this role as one of the many cast upon her, even that of the vicious vengeful wife in which she is cast in Mathilde’s novel, described in the play, Master. Her performance is so superbly dominating, by sheer theatricality, that it is never, nevertheless, melodramatic. She gains moral stature even at her most bitchy moments, for an actor cannot, in my experience, have captured the complexity of the networks of emotion that link love, loss, jealousy and defence of one’s self-esteem as well as she. The scene where she comes to understand Hilde and recount to her the death of her son, and her husband’s carelessness as a supposed master builder in causing it, as unbeknownst to both women, Henry listens to them in the background is a master-class in the actorly exhibition of her role, in that of the ensemble of actors, its direction, setting, lighting and realisation.

Of course, this was a play, too, with more laughs than Ibsen’s version. David Ajala in swimming trunks as the ‘cock block’ trendy architect Ragnar was a joy to see in so many ways.

This evening was fulfilling in so many ways too, but I was tired and wanted to sneak back to my hotel room. Thankfully, Claire was present, and she suggested alternatives a visit to ‘her club’ in Bedford Street, the Club it said over the door for Acts and Actors.

Claire is a kind of master too by nature and nurture. Her grandmother had been a variety entertainer, her mother an actor of great versatility (as well as a dear friend and ex -student of mine), but she excelled as a character actor. From the very beginning, Claire learned the mastery of how to achieve effects on audiences and had created shows that made audiences laugh, cry and/or reflect, even in working on representations of great artists no longer living

Still a young woman, she auditioned as both a Lady Ratling, a status hionour for a female entertainer, and as an A class member of this club. – here on the beermat they gave us is its other title.

Claire is going through a bad period after the death of her mother and is entertaining those doubts that come on all of us to warn us that our worth is never validated unless we provide the energy to do so for ourselves. I know this will come. Claire spoke of working again at her career. Meanwhile, she toured the club for my sake behind its humble door [its internal aspect only is humble) in Bedford Street.

As you ascend the stairs to The Jester Bar, the stars glow brighter, even those lost to us now.

All for now. Tomorrow is a busy art day.

With love to Claire and you.

Steven xxxxxx

One thought on “Mastery? The limits of achievement”