‘So I have taken to projecting myself – a sort of caricature of a toff. … don’t you think it is ironic that to fit in to this alien society I have to highlight and exaggerate the differences between myself and the people I want to get on with’.[1] This whimsical blog comes from reading: Kit Fraser (1985) Toff Down Pit London, Quartet Books.

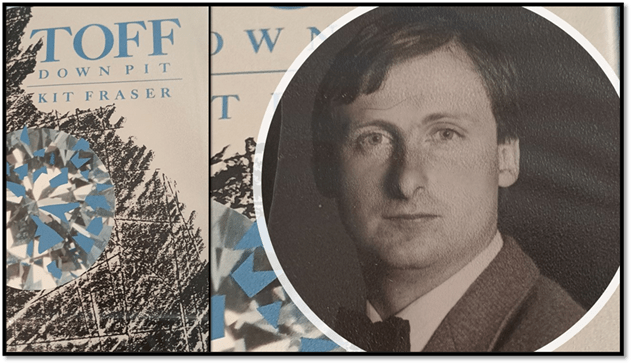

Kit Fraser not only is, by the standard terminology descriptive of the upper-middle-class entrant into the life of working-class communities at the time, a ‘toff’, but (see above) he looks like one in his publisher’s photograph. And he writes as one in this peculiar little book, telling of a social experiment, no doubt based on those of George Orwell, in which a journalist at the beginning of his career on a provincial newspaper, decides to attempt to work and live as a Durham miner for a time.

Moniack Castle

Kit Fraser was born at Moniack Castle [above] and returned to live and marry there, running a wine retail company. Nothing in the book he wrote of his life in Durham really ever explains why this project mattered to him, and by the end, he appears to have just become bored with what he presents as the limitless triviality and boundedness of working-class life: ‘bored of hearing about the three Fs: fights, football and fanny‘. [2]

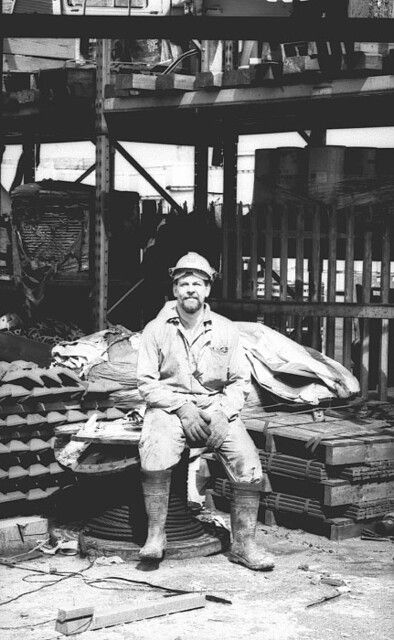

I took this book into my collection, mainly about the Great Northern Coalfield, because it seemed a new perspective. And you do learn something – why, for instance, the Westhoe colliery miner below is wearing wellies, for the Westoe sea-pit was notoriously soaked in water. But when I gaze at such photos, I don’t, I hope make assumptions about this man, nor see him primarily as the representative of a social class, though he is that too.

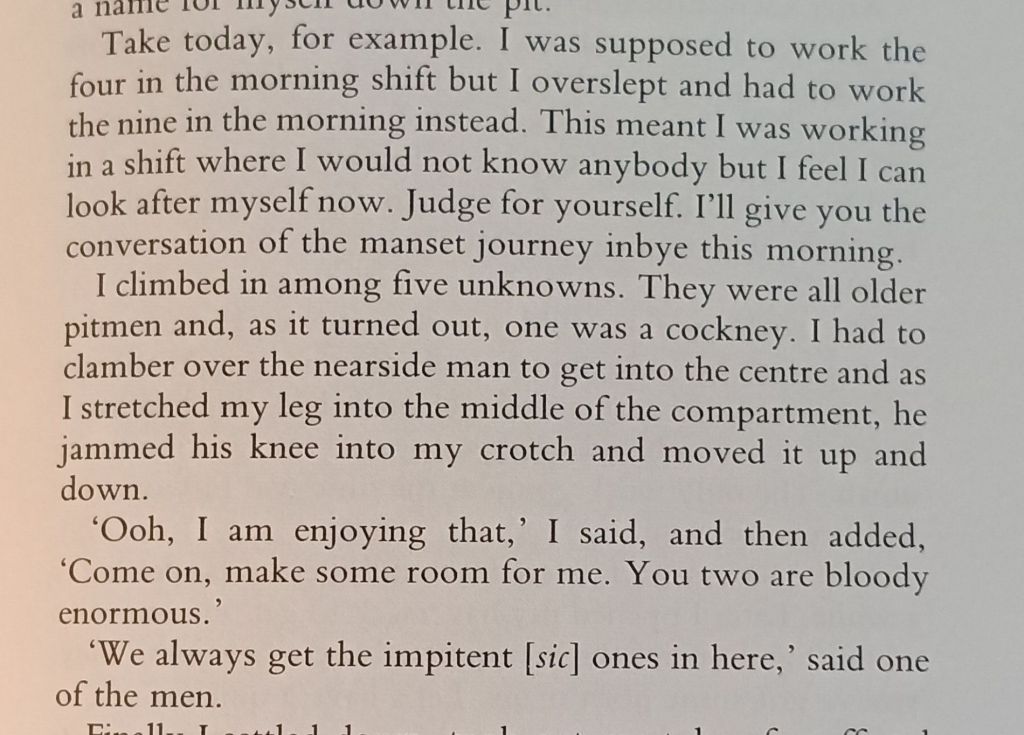

Kit describes the miners he sees as bigger, more energetic and stronger than he – indeed the joke even the men make, with its eye on the constant conversations about sex with ‘a lass’ , is of their potency. A potency he lacks. The following passage with its sexual play even takes that a stage further, although with no hint that the play carried any intention of desire – it is, as it reads merely a comparison of big strong manual masculinity against over-mindful self-conscious bourgeois failure as a ‘man’ that is feminised and or removed from male status, in the body at least. It is a passage about how Kit has learned to deal even with men he does not know:

Kit Fraser (1985: 51) ‘Toff Down Pit’ London, Quartet Book

Playing off against them, his smaller stature, his joking acceptance of a larger miner’s leg rubbing against his own, he accepts the label of ‘impotence’ without challenging it. Even his layer first achievement of heterosexual sex is presented as yet another sign of the same class iconic failure of masculinity. Having found what the other miners say he should be questing ‘loose fanny’, the result is less that confirming of Kit’ potency: ‘So with a minimum of foreplay, and with a penis that obstinate refused to fully erect, I penetrator the lass and after a series of hurried little thrusts had an ejaculations of sorts’. [2]

Kit still can’t wait to share the news of the loss of his virginity. Talk of sex is the only way in which mind enters eorking-class talk in Kit’s characterisation of the men of Westoe pit.

Ibid: 109

I find the tone of all this rather puzzling. Is Kit attempting to understand or just despair (or feel disgust) at his horny-minded mining colleagues, with their lack of empathy for any vulnerability in those who could easily become sexual prey. The tone is eventually a kind of judgement. The footnote attached to the star on Berny Martin’s name makes that clear, informing us that Berny ‘is now in prison for sexually assaulting his own sister-in-law’.

In the end, all this makes me rather less able to find value in this book as reportage: the view of working-class masculinity is too unrelenting in its reduction to stereotypes. Occasionally, diversity does emerge from what seems otherwise to be communal homogeneisation. Twice we hear of a ‘homosexual’ or suspected ‘homosexual’ (that suspicion is even allowed to haunt the community’s image of Kit, though we are disabled of its truth, but no flesh is put on the bones of that appearance in a word. Women never really gain character either, even the ‘loose fanny’ with whom Kit eventually scores. It is as if they had no significant mind or heart into which to enter, other than through their stereotyped playing of a role.

Most of the story takes place in South Shields and Westoe Colliery, and I yearned for more detail here of the place and its feel other than as the site of work, residence, or pub crawling. Old pictures of Westoe Colliery still recall a mystery that Kit will never lift from it. Feel theze pictures yourself:

When, at the end, Kit contemplates leaving ‘boring’ Westoe, he thinks of the chances of attempting coal-gace work at Sacriston Colliery, disliked by miners because its coal-seams were thin ones. He never goes to that place which is near where I live. I ached for a description of the time when any of its overground buildings were visible.

Sacriston Colliery

In the end, we get no nearer to understanding the class system operating in the ninteen-seventies in Durham, even as Kit would have thought of it. Tje term ‘toff’ is supposedly used ironically, but it does not quite work that way. In my title, I cite this:

So I have taken to projecting myself – a sort of caricature of a toff. … don’t you think it is ironic that to fit in to this alien society I have to highlight and exaggerate the differences between myself and the people I want to get on with.

The projection of that stereotype never, in fact, stops, for it is fairly clear that Kit feels that no deeper connection is possible between classes but a kind of ironic playacting. I write this blog in some disappointment and in certainty that this book won’t stay in my library. Perhaps I will donate it to the socialist bookshop whence I bought it.

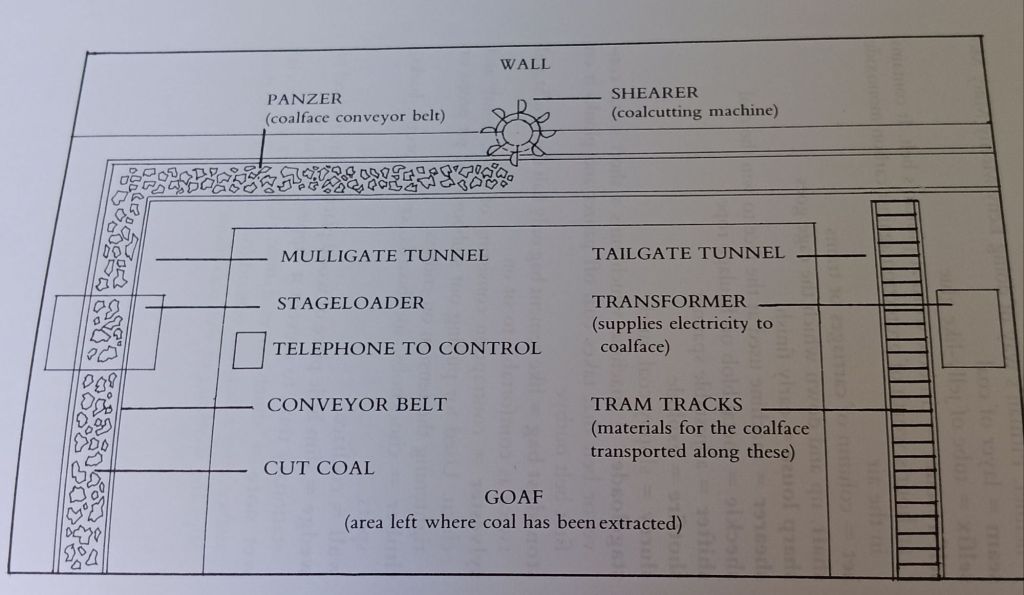

On the other hand, I do value this labelled diagram from it. It and the book’s glossary is one of the clearest explanations of the terminology of Northern mining I gave read, and indeed the book glories in it, demanding that a reader makes themselves proficient in this alien vocabulary.: of goaf, panzer and the directions used in pits, and in Tom McGuinness painting titles, inbye and outbye.

That’s all

All my love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Kit Fraser (1985: 42) Toff Down Pit London, Quartet Book

[2] ibid: 125

[3] ibid: 107