Personal, institutional, or collective. What is Malpractice?

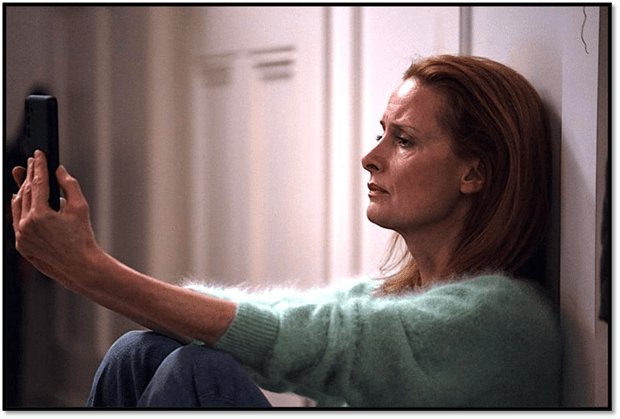

Tom Hughes as Dr. James Ford in the midst of a hospital discharge mental health assessment, which becomes the focus of the first malpractice claims levelled against him

I started watching the series Malpractice only in its second series, and then because I had heard that its focus was on mental health – the area of NHS work of which I have most experience in a series of roles. Those roles were, if it helps: 1. as a residential and nursing home support worker, 2. a Student Social Worker in residential and rehabilitation care, 3. An Older People’s Mental Health Social Worker, 4. a training and then two years as a trained Primary Care Graduate Mental Health Worker (roles invented in the 2000 NHS Act) ,and, 5. A Severe and Enduring Mental Health Outreach Team Social Worker, as part of a multidisciplinary team. The relevance of all this might be clearer later, especially to the early episodes of the series.

After watching the whole series, I had a rather mixed reaction, although one that changed into two dominant responses that differed entirely in character. The introductory episodes caused me quite a lot of stress involved in identifying with various characters involving ruminations on the kind of culpability of ignorance, poor execution, or error that might have in my past career have brought me nearest to an outcome that might be, fairly or unfairly, labelled personal malpractice.

The concluding episodes contrastingly were predominantly evaluated simply as fictional narrative, with little or no demand on me to identify with the characters or their decision-making. In these episodes, the basically well-meaning characters were exonerated whilst those who had throughout successfully hidden the rather extreme malice of their plotting in their own self-interests were found out and brought low.

Plots of such simple ‘poetic justice’, by which we usually mean justice achieved at the cost of a believable story, are rare in modern drama. But for me, these turns in tne unfolding of plot relieved the stress of the early episodes, turned what had occasioned meaningfully painful reflection on my past practice, into something that enabled me to become the passive viewer of a satisfying but entirely unrealistic drama, a smugly relaxed observer of a neat ending where even uncertain virtue was rewarded, and clear villainy punished.

I need, however, to take all that a little further, for the piece was stressful only at any point where it dealt with malpractice as a personal issue. When that negative stress was relieved, and the events were being experienced as at worst eustress, wherein malpractice is generalised at institutional or collective level. It became simple pleasure to watch Malpractice when even institutional malpractice was explained away by the actions of one bad actor, a villain representing the worst motives of capitalist accumulation. Even capitalism can be saved from blame in the final resolution: the villain being merely one morally bad man, though one from an equally morally bad milieu.

Adam Sweeting reviewed the piece for The Arts Desk and wrote thus of the realism of the piece, although the ‘uncomfortable plausibility ‘ he describes stopped for me being true in the final episode. Sweeting says:

Writer Grace Ofori-Attah had personal experience as an NHS psychiatrist, which has undoubtedly helped to lend the show a sense of frequently uncomfortable plausibility. The real-world NHS seems to be in a permanent state of crisis involving funding, staffing and horrific waiting lists, and that perception is accurately mirrored here. [1]

For me, this explanation fails massively to see where and why the writer’s personal experience may have helped her and where it failed her. Where it failed, it failed culpably – in the characterisation, for instance, of people with forced to wear diagnostic labels in the mental health system. A key turning point in the drama revolves around a character claimed to have a ‘borderline personality disorder’ (BPD), perhaps one of the loosest and most abused of mental health labels. It is so label.productive of resistance in staff to understand the condition it masks or to address its amelioration. Where it succeeded, it is sublime.

BPD is used (for now take my word for it for almost most psychiatrists who mainly remain committed to the diagnosis might disagree) to explain a wide number of negative (and no positive) personality characteristics, none of which seem to be a characteristic held by the character within this play. Not even stereotypical of the diagnosis then, she is seen as a regressive and quiet woman with a dependency on one doctor, amounting to obsession both sexual and romantic.

She is the problem on the ward in the view of its staff, a very accurate description of the treatment of people with the label. Her problematic nature involves stalking Dr. Ford, whose supposed malpractice is the main focus of the first episode and a half. The result of her stalking is a photograph of him kissing and embracing his clinical supervisor, with whom he is currently having a sexual relationship.

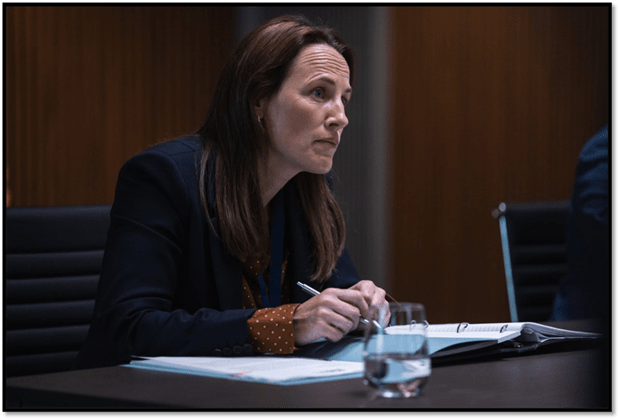

Ford and his clinical supervisor and manager, Dr Kate McAllister (Zoë Telford), seen at a point before the audience know, through the activity of a ‘BPD patient that they are in a relationship that is in itself a malpractice.

But this is not enough to show the unstable nature of our understanding of what medical malpractice is involved, so let’s share some spoiling narrative. In a maternity ward, Dr Sophia Hernandez (Selin Hizli -below) calls in Dr Ford to give an assessment of a patient she wishes to discharge but about whom other staff have concerns.

Ford attends but reluctantly because Kate McAllister (his supervisor – and girlfriend though we don’t know that yet) has sent him on an urgent community health assessment where the police, social worker and other doctor are waiting to secure possibly forced access to decide if involuntary detention under a section of the Mental Health Act for either assessment or treatment is required. His hospital discharge assessment, therefore, is grossly inadequate and superficial, and he fails to follow through with advice to the patient, advice he leaves to Dr Hernandez.

Arriving at the assessment in the community, he finds local people angry at the presence of what seems like police overkill (and that is not at all unusual) and chaos abounds. The patient, Adei Bundy, as Kathy Miller, who is pregnant, seems not supported by her husband and is fearful for her daughter, who Dr. Ford takes in his arms and secures her in another room, persuading Kathy to accept voluntary admission, where she is likely to be detained if uncooperative.

All of this is in my experience, either as an observer or a participant, though I never finished Approved Mental Health worker status training in order to be considered competent to assess patients for admission. However, I knew the range of the situations – and the room for error involved – not least in delay to attend on time caused by being in the grip of other things that named themselves as priorities. It was all this that made my anxiety high, not only for Dr Ford but that vulnerable person that was myself in my memories and others, not least well-remembered, notably the patient under assessment.

However, we are soon to learn that, despite appearances, there are culpabilities elsewhere – especially it seems at first, in Dr Hernandez, whose management of the maternity ward shows her weakness in mental health issues and in appropriate discharge decisions in relation to this. All this comes to a head when Kathy Miller gives birth prematurely. whilst still in the psychiatric ward, delivered by an inexperienced Dr Ford on the floor of a corridor.

Meanwhile, the Trust has referred his practice to the Medical Investigation Unit (MIU), even taking that further when Ford tries to get more information from Hernandez and is charged (somewhat fairly) with bullying. He is seen by management – security guards being present. The Trust – presented as Yorkshire Health trust (YHT) – have him suspended with immediate effect and escorted out.

However, the investigations of the MIU and the actions of the patient with the BPD label lead to the knowledge that he is in a relationship with Kate Mcallister. Kate, however, is offered promotion if she ends the relationship and keeps the focus of MIU on Dr Ford. She agrees. It appears that the focus of malpractice in truth and in our eyes as a viewer is now falling on her.

By now, it is clear that the centre of the drama is MIU. Not having seen the first season, I had not known that wouldbethecase. David Sweeting says then helpfully that:

The MIU investigators Dr Norma Callahan and Dr George Adjei (Helen Behan and Jordan Kouamé, pictured below) are returning from the first series, and will presumably feature in any future ones, and their forensic adventures sometimes make Malpractice look like Line of Duty with doctors. The MIU certainly seems to wield a remarkable range of powers, like trawling through phone records and having access to police traffic surveillance cameras.

By this point our sense of individual malpractice has been well lost as guilt becomes collective – though still harmful because uncommunicated to others ( and us as viewers), but especially uncomunicated to parents and carers and least of all by hospital managers and administrators. Guilt flows between the psychiatric and maternity units, the Trust, and ultimately its Management Lead as the scenario becomes more unreal. Sweeting says:

But they say a fish rots from the head, and a trail of cynicism and turpitude leads steadily upwards towards the boss of the hospital’s trust, Dr Eric Sawers (Rick Warden). It seems there may be more to the threatened closure of the psychiatric unit than merely its dubious medical track record, while prioritising costs over patient safety has led to hideous suffering for numerous mothers in the maternity unit.

Indeed, we are to find that Dr. Sawers has a huge financial interest in the mental health unit being found faulty and closed, its buildings sold off. The lead of the MIU in particular emerges as a cool-headed sleuth, somewhat unbelievably, but given a messy home life to compensate.

Meanwhile, the other MIU investigator is forgiven by the parents of a boy who died and had originally charged him with malpractice but were now disgusted because the rest of the Trust scapegoated him. Given the rather poundingly obvious unlikelihood of some of this, it took great actors to carry it off – and they did.We ended with a satisfying drama of moral validation – where the basic goodness of Dr Ford is seen. His eventual willingness to accept some culpability and his care for his patients and Mrs Miller’s girl-child (brilliantly conveyed even whilst we thought him overwhelmed entirely).

Indeed all power to a great cast:

But I wonder if I would have noticed just how good all this was if the writing and direction had not been do full of narrative secrets that left right to the end the finding of an arch-villain and nearly as near to the end the generalisation of responsibility for a broken health service chronically under-resourced, especially to care for the highly vulnerable and structurally disadvantaged. There is danger in over- generalising and more in looking for an arch-villain to blame where needs are not being met. There is also danger in treating all the faults in a system as those of individuals, as the current system of scapegoating often does.

However, a programme like this is right to resurrect individual guilt. For without it, we will never take responsibility for generalised and shared guilt. And now whilst the sharks of private enterprise are sweeping under Trump’s banner into our health service, warmly welcomed by a Labour Government – [do you feel Nye turning in his grave?] – we cannot afford not to take personal responsibility.

All for now

Tomorrow to Amsterdam

All my love

Steven xxxxxxx