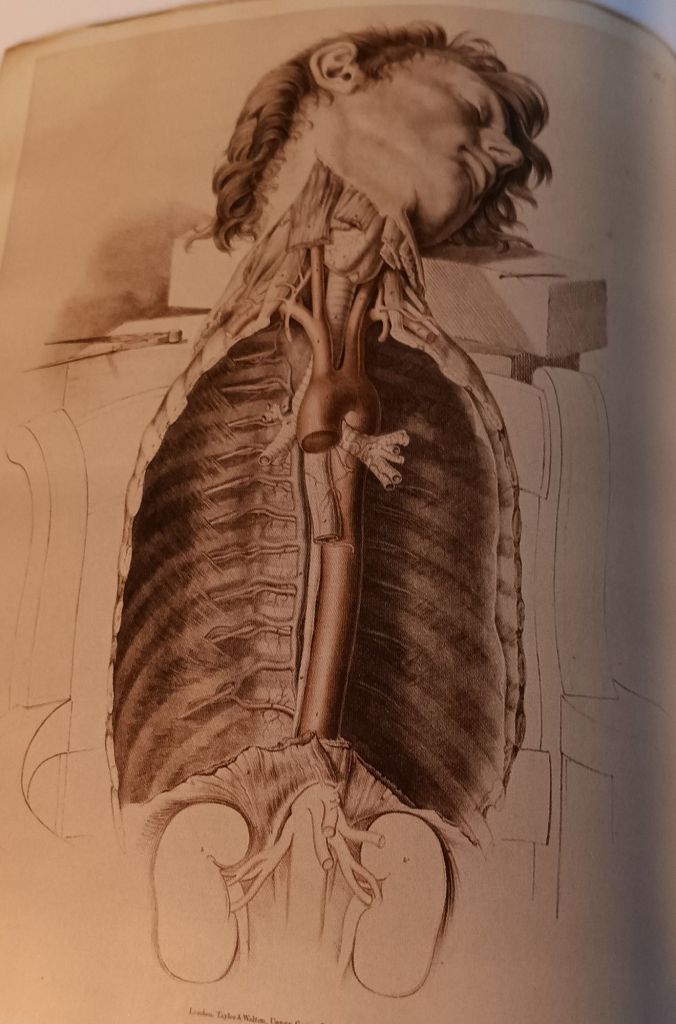

Gaze on the picture above and any anatomical learning, or at least a good proportion of it, gets absorbed in gazing at the beauty of the head and face of the model, which though logic (and that ‘little knowledge that is a dangerous thing’) tells us that this is the head and face of a corpse, we continually resurrect it in our imagination as the face of a young man sleeping, perhaps near to us; perhaps a head in which every way in which the hair falls down the face is known, loved and desired.

A little knowledge would be a dangerous thing here for Sappol shows us that its maker, Henry Maclise, brother of the Victorian narrative painter, Daniel Maclise, whose male figures appealed to John Minton, continually boasted that though he had access to the vast resources of corpses available to University College London, he used live models too to prosecute his art, and perhaps his pleasure (although maybe only visual and voyeuristic) if Sappol’s hints are to be heeded.

Anatomical drawing has a bifurcated history, but in medical contexts, we think of it as an art only in as much as it shares an equal dependence on anatomy in life-drawing, especially in training in that domain, on accurate knowledge of the internal structures of the body that shape external embodied form. It is not used though in anatomy, we tend to think, as a way of engaging in demonstrating formal beauty, except perhaps in a cognitive grasp of the perfection of natural structure, or in narratives of desire and other human interaction in which complex desire may play a part. The latter art proper does do. Think of Henry’s brother, Daniel Maclise’s playful take on Shakespeare’s As You Like It, where desirous eyes go anywhere and everywhere, delighting in the queer aspects of trans-sex-gender desire.

Daniel Maclise’s take on As You Like It

In anatomy, as we tend to think about it, the art of drawing serves the purpose of manifesting graphically a means of increasing knowledge of the internal structure of bodies, usually confining itself to the specific parts of the body about which information is intended to be conveyed. The model of such a paradigm of educational and training anatomy is of course Gray’s Anatomy.

But not so Henry Maclise. For that head and face on his drawing above are unnecessary to the educational purpose of manifesting the main arteries of the neck and upper thorax. So, of course, are the lower abdominal viscera, but these are drawn, in recognition of that perhaps, in fading lines and without any attempt at depicting volume and mass specifically. In contrast, the lips, cheeks, and even hair of the young man invite our touch on their living solidity but also restrain it lest we wake or offend him.

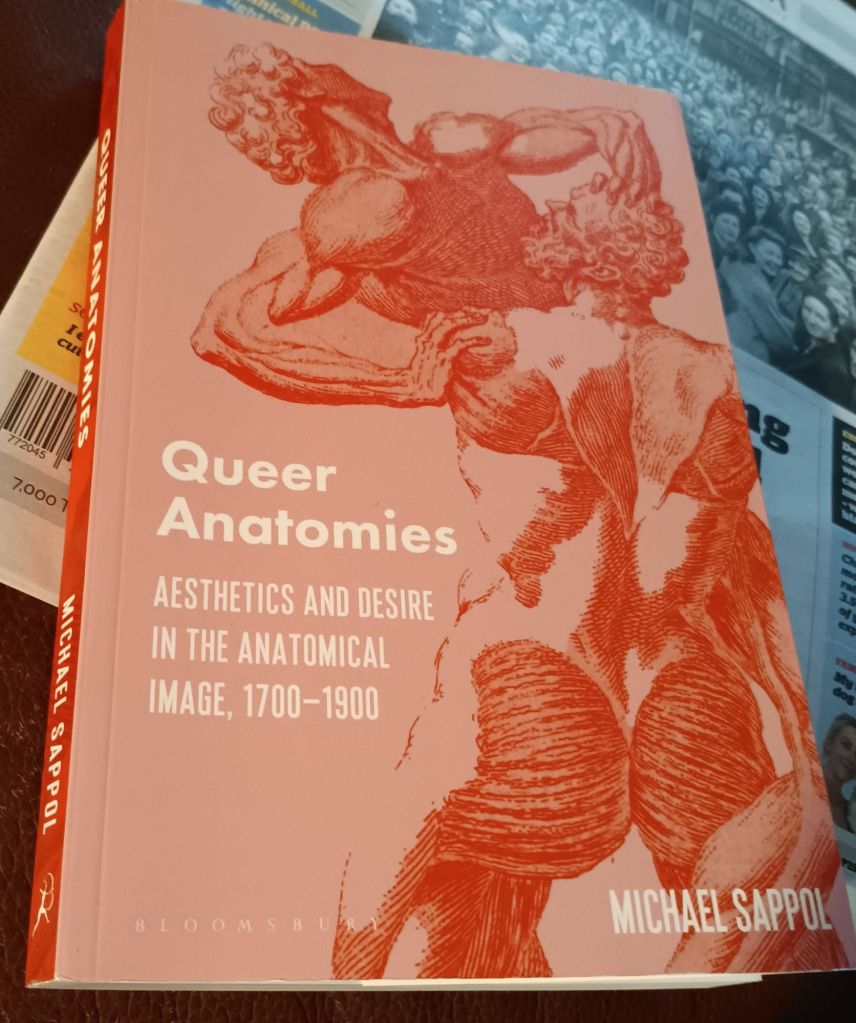

Sappol tries a new way in investigating art history that does not rely only on the dry stuff of stated intentions by the artist, though it uses those too intelligently. It does so through reading them more deeply than is usual, but shows that we must extrapolate from the sensations accorded at the eye, through haptic imagination, if we are to find the histories that public history buries (sometimes even within narratives of possibly never-enacted desire) – queer histories. Of course, Sappol relies on a growing tradition that the turn to reactionary normative binary categories recently has not as yet killed off entirely.

Sappol’s book has plentiful references to Anthea Callen to whom the field Michael Sappol works in owes so much, and whose book on anatomy is a useful, but not totally necessary (since he uses pertinent quotation from it) background reading; as a pathway to seeing the significance of Sappol’s work. Read Callen anyway, however. She is so good that when I first read her best book,‘Looking At Men’, all I could do is gush over the fact that it liberated me from the stultifying thing that was art history education as provided by the Open University at that time. Read my brief reference at this link. But this book tells its own story. In a ‘blurb’ given to quote on its cover, Callen describes Sappol’s book accurately thus: ‘Wearing its erudition lightly, Sappol’s witty take in ‘Queer Anatomies’ informs, delights and challenges in equal measure‘.

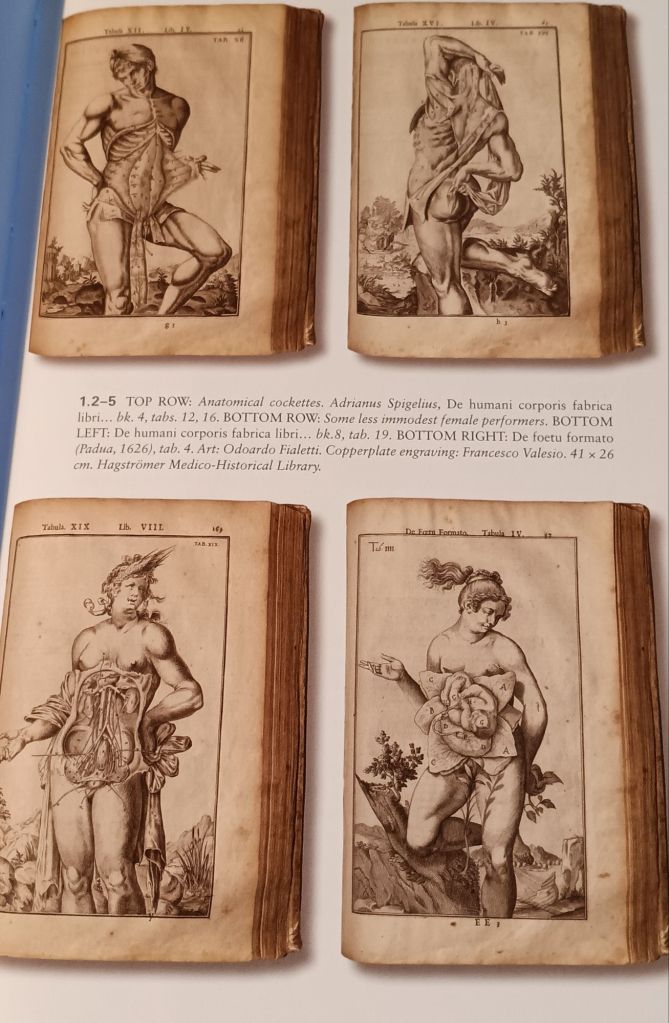

Of course, anatomy was not always as straight-laced by its superficial purpose, and this is why the book starts its historical survey in 1700. There are very playful young men courting attention to their bodies – inward and outward attention in the early tradition, prior as it were to the invention of sexology. A picture alone will suffice – just go to the book for more. That book is excellent in painting the concurrent histories of art, medicine, and graphic publishing through their contexts such that the queerness of Maclise’s contribution stands out in its own time. Only one of the lovely ladies or coquettes [cockettes is Sappol’s term] as surgeon and essayist Oliver Wendell Holmes describes Vesalius’s anatomical figures are women in the page below. Sappol thinks that Holmes’ gender blindness here is a purposeful one – stopping him from seeing the real possible object of his nineteenth-century desire.

Certainly, these men playfully but, surely purposely, show off their fanciability. Nevertheless, this may be a way of integrating the knowledge anatomists need of the body with signs of its its function, to animate bodies in their common usage in the contexts of play, desire, and self-manifestation. This isn’t the case in the nineteenth century drawings of Maclise, which use the beauty of the unconscious and un-self-conscious offering of themselves to the gaze, not only for educational but the purposes of manifesting human beauty and the role of desire in appreciating that beauty.

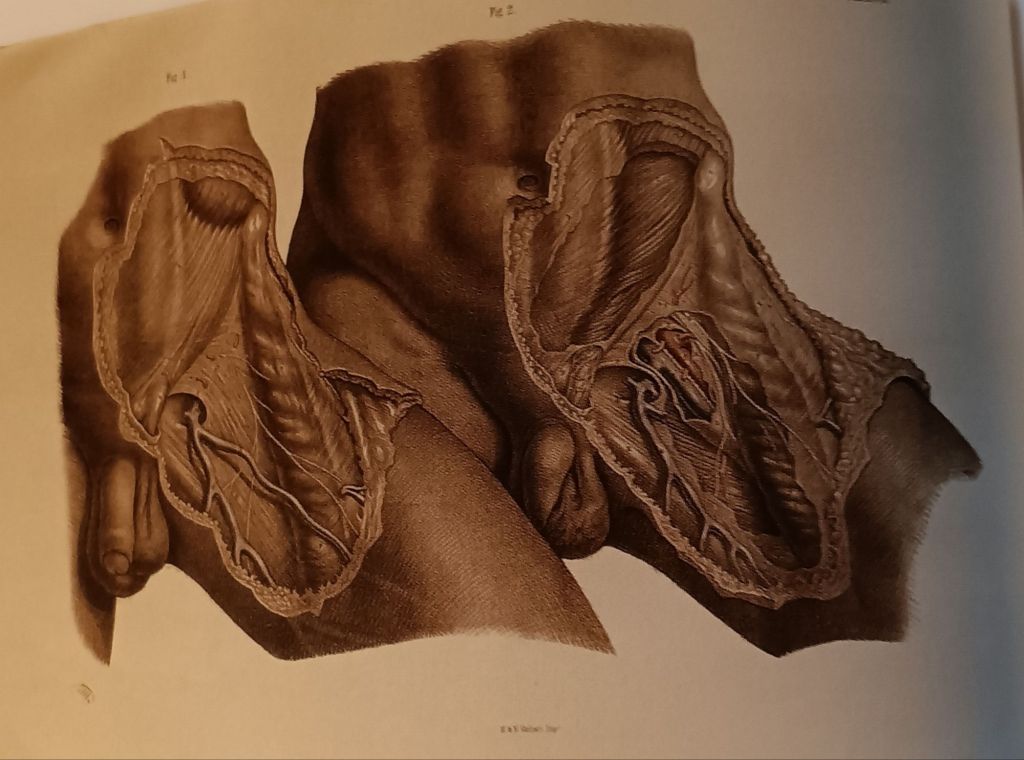

The way in which Sappol illustrates that, and extrapolates on its possible contexts and consequences, is to invoke queer theory both in terms of its articulation of queer sexual narratives but also the intrinsic queerness of desire however labelled: as a force uncomfortable within societal norms.Take the illustration below:

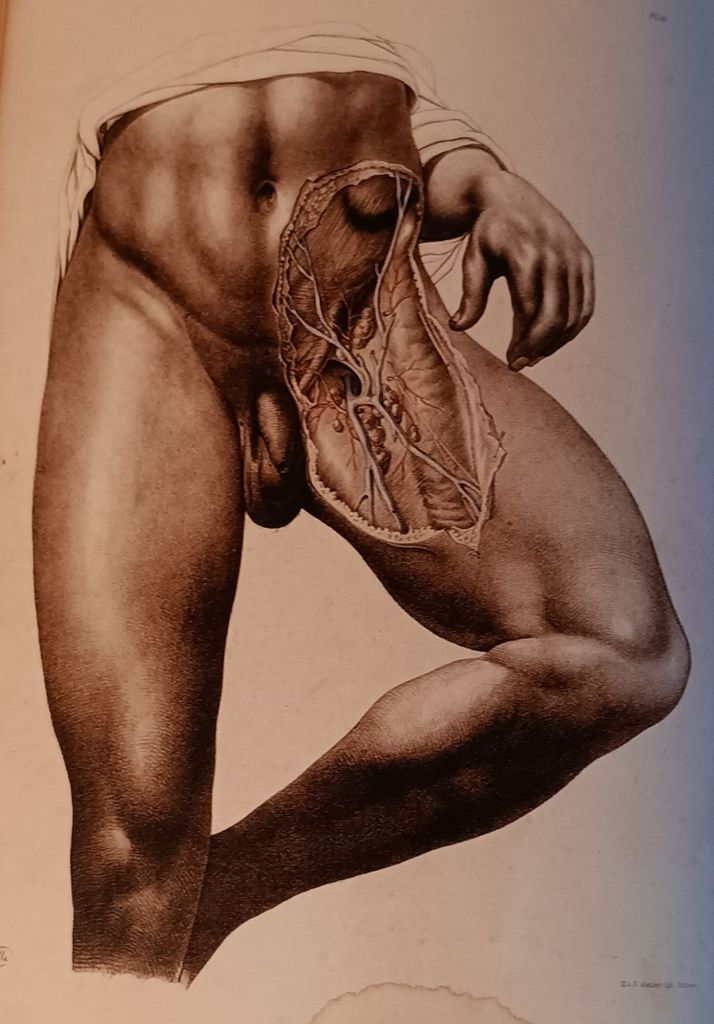

The feature Sappol concentrates upon here is the redundant beauty of the hands and, even more, the redundancy to the purpose of anatomical education of their wide scale of signification. They are placed next to tools used by specialist hands – those of both the artist and the surgeon – as if the excess polyvalency of the illustration’s functions were being forced to our attention. But these hands also show the flexibility of their internal articulation and their role in the function of touch as the hand curves to press its fingertips into the wood on which it lies. Is this touch sensuous or expressive? After all, in order to show the inner deep arterial webs, the corpse model’ leg has been removed surgically on one side – of little consequence to a corpse, though not so of the living body other signifiers here reveal, not least those hands, reaching and grasping – one to the hand tools of artist and surgeon, the other to the chasm of the exploratory wound necessitated in anatomy.

Sappol shows that the functionality of hands were seen as part of their beauty by Maclise, but surely here, they and their beauty and the actions of desire that they can manifest – touching, feeling, caressing – are entirely redundant- for the anatomy of the hand is not implicated in the educational purpose of this picture. And if true of the hand, what of the depiction of the penis and testicle on the body exterior, hanging in what was once the space between both legs but now exposed. It is not necessary to see this penis at all anatomically speaking.

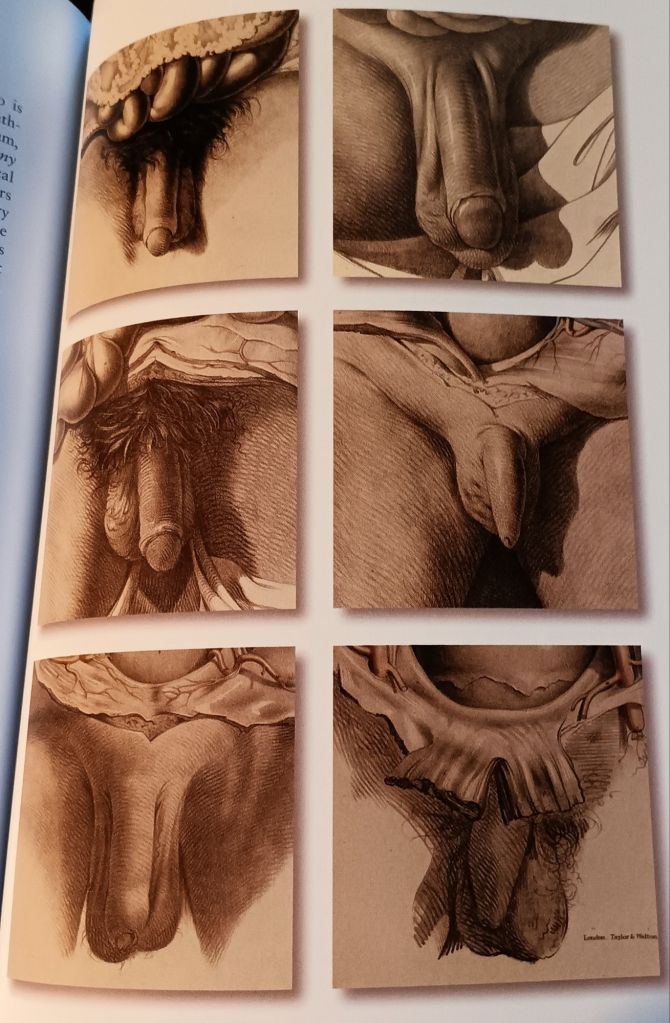

Sappol has a whole section on ‘redundant penises’, which he also playfully calls a set of ‘dick pics’, to show both the inappropriateness of this nomenclature and, at a deeper level, the fact that it could be exactly a function of these details from anatomical drawings which in every case did not belong to descriptions of genital anatomy and were irrelevant to it. The pictures amaze because of their variety and lack of obvious stylization or typology. They range in size (length, volume. and density), state of foreskin development or presence, effect of relative engorgement, and the state of the pubic hair – shaved totally or partially or with thoroughness, appearance of volume and relative thickness of hair or, and this is creepy, shading by the overhang of redundant skin from surgery .

The most amazing variation, however, is in the set of penises relative texture. for texture is, of course, a ‘touchy’ subject and implies touch or the imagination of touch – sometimes called hapticity. Effects like this are caused in art by the density and variation of brushstrokes in painting (gouache or oils) or the urgency and density of hatching and cross-hatching in drawing. These effects are not particular to the kind of drawing that aims to realise the feel of the corporeal so that it can teach surgeons the need to acclimatise to cutting dense flesh. You find both effects in oil and crayon or pencil heavily indicated in Renaissance and seventeenth-century art – Rembrandt and Titian, for instance. See some thoughts on this, for instance, in another blog on a concept I used to call homosomatism at this link.

Texture is everything in these pictures both as a surface feature (where matt and glossy effects matter) and at the level of the touch of pliable and plastic mass. It applies to the variation of testicles and testicle sacs and their interaction to appearance. Sappol is convinced that Maclise was inventing an innovative kind of figure drawing in which detail and whole were open to disegno effect (in Vasari’s rich set of associations), even in the framing of the figure or the figural part executed. The best example Sappol thinks is that below:

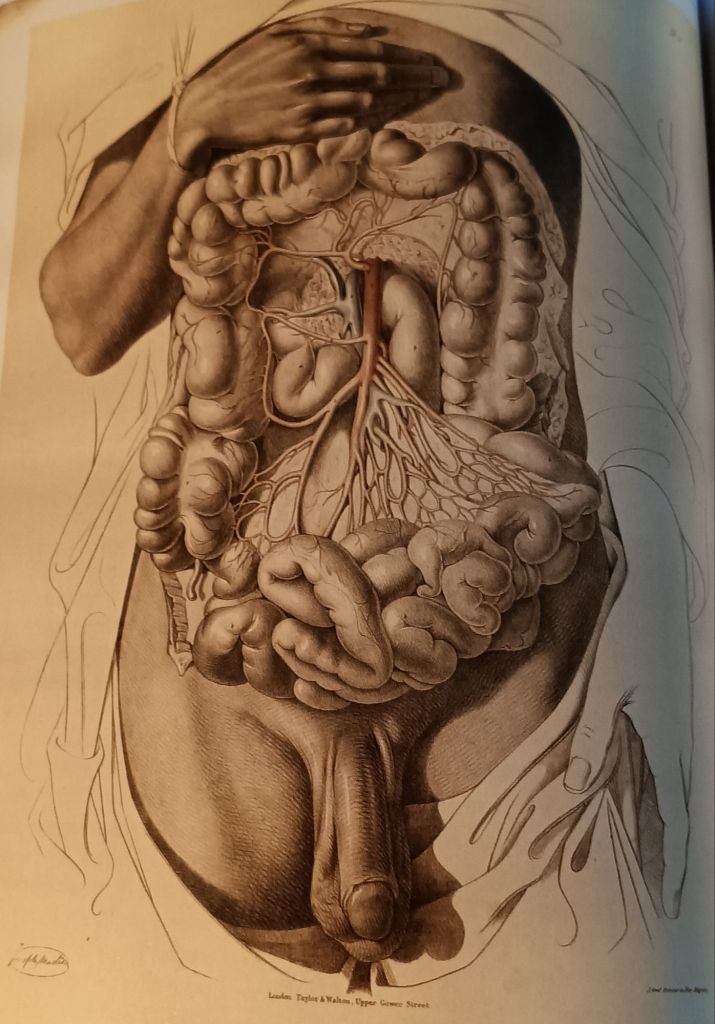

Here both the redundant penis (a shining example) and the redundant hand seem to frame the figure so that the frame of textiles is allowed to become only the mere suggestion of folds, unimpressive in relation to the folds of the body’s viscera in design and texture. The hand on the left is equally faded to emphasise only the penis to which it hangs parallel. But note the curvature of the upper hand, which seems to emphasise the touch of skin on skin, irrespective of body cavities. In a beautiful section of his book, Sappol even expands the detail from the drawing below of where the hand of this mutilated but beautiful figure touches its own skin.

He says of it:

Michael Sappol (2025: 122) ‘Queer Anatomies: Aesthetics and Desire in the Anatomical Image 1700 – 1900’, Bloomsbury

Those orphaned phrases, bereft of the authority of a parental sentence, like ‘Exquisite sensation’, are characteristic of Sappol’s queer style but I find them very effective. This seems to me art critique of a very high order, for it takes us back to the work and we see what we might have missed – in the totally redundant characteristic (for an an educational anatomy book) even of the self-caressing fingers of one hand, and would have been the worse for not noticing.

Even more touching is his comment on a drawing that had shocked me in my feeling of its queer (in every sense of the word) strangeness and yet obvious Ness. It is a picture of two anatomical figures that appear to be in the act, or approaching the act, of touching their lower bodies together intimately. How do you see it?

These are clearly different men and we know that mainly because of the distinctness of each of the men’s penises. At the time of publication (1856) an expert reviewer, from the Edinburgh Medical & Surgical Journal, complained of “the crowding of two anatomical figures on the same page’. Sappol wonders out loud that, though for a physician comparing examples of varied levels of anatomical depth in a ‘close pairing makes the comparison easier to see’, that perhaps the reviewer became uncomfortable, since strictly speaking the page is not ‘crowded’, he sensed that these figures positioned thus also gave play to ‘an opportunity to stage a teasing contact between bodies’ (Michael Sappol (2025: 122f.) ‘Queer Anatomies: Aesthetics and Desire in the Anatomical Image 1700 – 1900’, Bloomsbury ). Who am I to say, except that the picture gave me pause even before I read what Sappol had to say of it.

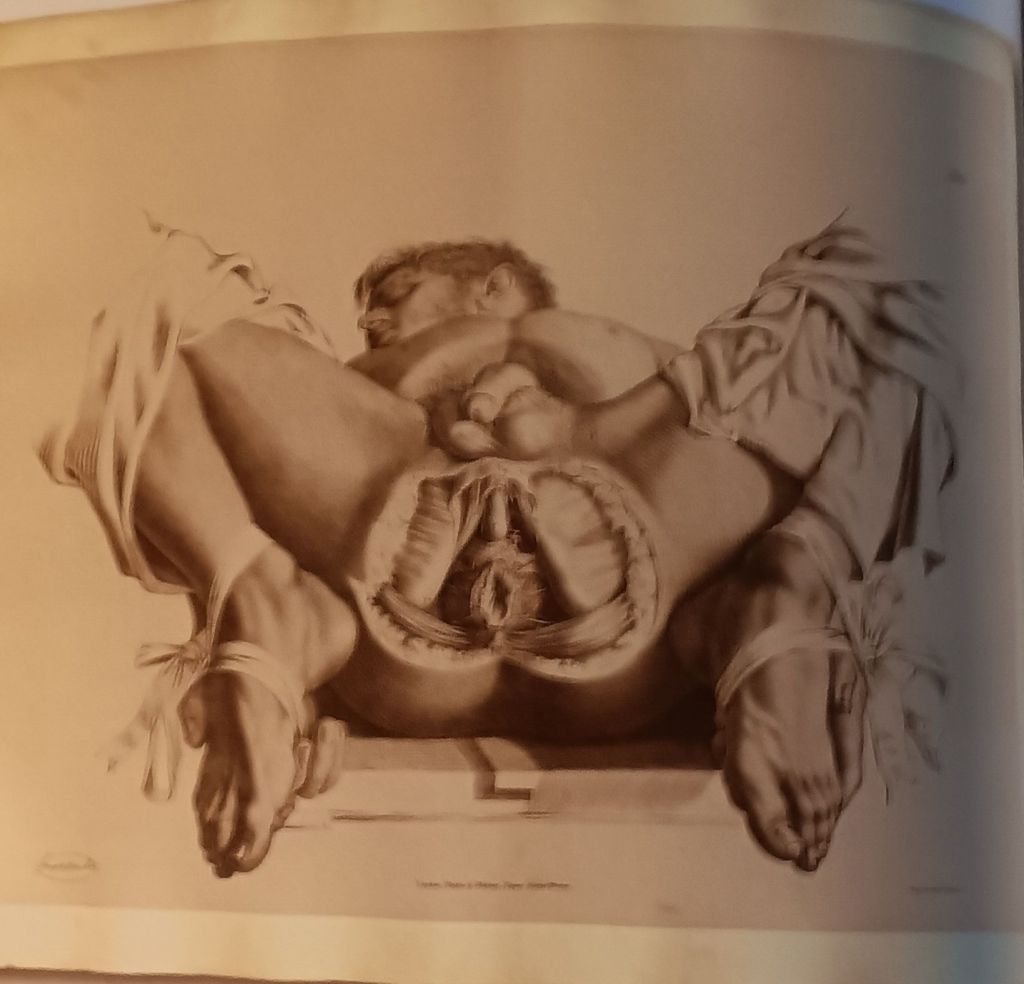

One of the issues that Sappol discusses, and is also raised by the reviewer of the book in Gay & Lesbian Review, is that if any deviation from norms identifies the queer, there is no longer a case for examining the implications for LGBTQI+ history irrespective of the contribution of queer studies, which is not specialised to LGTQI+ lives and biopsychosocial practices. Sappol’s work counters that by not staying entirely with the potential in anatomy for the sexualisation of the penis but also that of the rectum. The rectum is displayed in potentially queer pose and gesture in the illustration he picks out that I place below:

Again, the head of the male figure feels to be that of a living, if passive, man. The otiose display of the ligatures used to display the corpse model for demonstrating the precise area of the body is not only unnecessary but interacts queerly with the sense of life in those parts of the body not open to internal view of the body. But the focus of the picture on the open anus capped by a significant mound of external features of the genitalia, seems to make it, in Sappol’s account, ‘utterly indifferent to to the policing of representational boundaries that protect the category of Beauty from things like exposed rectums, testicles, viscera and anatomical destruction‘. Instead, Sappol goes on to say:

The rendering of anatomical rupture, violation, and destruction with sensuality and grace makes a scene that looks real and beautiful, which is to say true.

I have to say that this book is remarkably good – scholarly but witty and readable. It ranges outside the policed boundaries of ‘subjects’ as conceived academically and conventionally and brings back from their fuzzy borders real truths that are hated by run-of-the-mill academics not because of a genuine academic case but from the fear that perhaps the specialisms that rule our life are really there to stop us getting at the truth that matters.

Do read this book.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx