The stages of a long ovation: Gary Oldman honours his audience as Krapp.

I am starting this blog in the train home from seeing Gary Oldman in Krapp’s Last Tape in York Theatre Royal. It is a strange thing trying to find the one phrase or sentence of action or speech that stays with you after a great production like this, haunted as it was with so many ghosts of such phrases and phases. There are so many contenders, and some of them are silences, even darknesses. But Gary Oldman knows how to turn horror into poetry: the poetry of rhythms of inaction and action. Perhaps that is Samuel Beckett’s vision of his own career in words and moments.

Everything there, everything, all the – [Realises this is not being recorded and switches on.] Everything there, everything, everything on this old muckball, all the light and dark and famine and feasting of … [hesitates] … the ages.

The odd thing is that no theatre transports or moves one absolutely. That is for more than one reason. First, we are always aware of the materiality of theatre – its existence as active show and social event. There is in this play especially a need to make statements that matter or are turned into matter, at least to their maker, Krapp, who feels a ‘fire’ in him. That last statement I quoted, for instance, sums up the whole Earth – for ‘muckball’ is a literal analogy of the idea and word that is ‘earth’ and Krapp intends us to understand that he comprehends ‘everything’ that is on it – but most strongly the contradictions between binary states of being and perhaps even ritual – they are all part of the ‘light and the dark’ and both matter and perhaps are ‘matter’ – muck.

However, Krapp does not wish to speak to himself just in the here and now but to have his words kept and captured on tape, of which he may be the only listener. Nevertheless, the actor playing him must show that he he realises his words are ‘not being recorded and switches on‘ the recording machine as a result. Krapp, despite his insistence on his self-sufficiency, requires to be ‘heard’ again and by another – even if that other is only an older self, alienated by time from his younger self. It is all too earthy of him it seems to seek that his words be kept and stored somewhere . Similary, the ‘black ball’ he throws for a dog could have been kept rather than given away.

The problem for Krapp is his anality (hence his name – for Krapp can be held in or scattered). At best, as an anal character would see it – the hoarder that Krapp is – he can hold back and scatter at the same time. He thinks he can both both keep and give away what steals from his orifice (his attitude to bananas too) like any and every type of miser – cognitive, emotional (anally-retentive of his feelings and their expression). He says to the bony prostitute Fanny that he can STILL be sexy at his age because he ‘has been saving up for her all his life’.

Misers really seek to be in control of time and its passage: that is Krapp all over. He can move tapes back and forth, play with the extension of their ‘spoooling’, and catalogue them in sequence, but he is neither successful really in jumping time – he always returns to his omissions or in knowing how to select from it however well its sequence is recorded in Box and Spool number – nor able to stop his controlling attitude to it. The time that hoarders think of as theirs, and which they hug into themselves, is still victor over them – no matter how you try to give it away, encourage that it be stolen or just lost – perhaps even when it is thrown away into the dark like so many pieces of half-eaten banana.

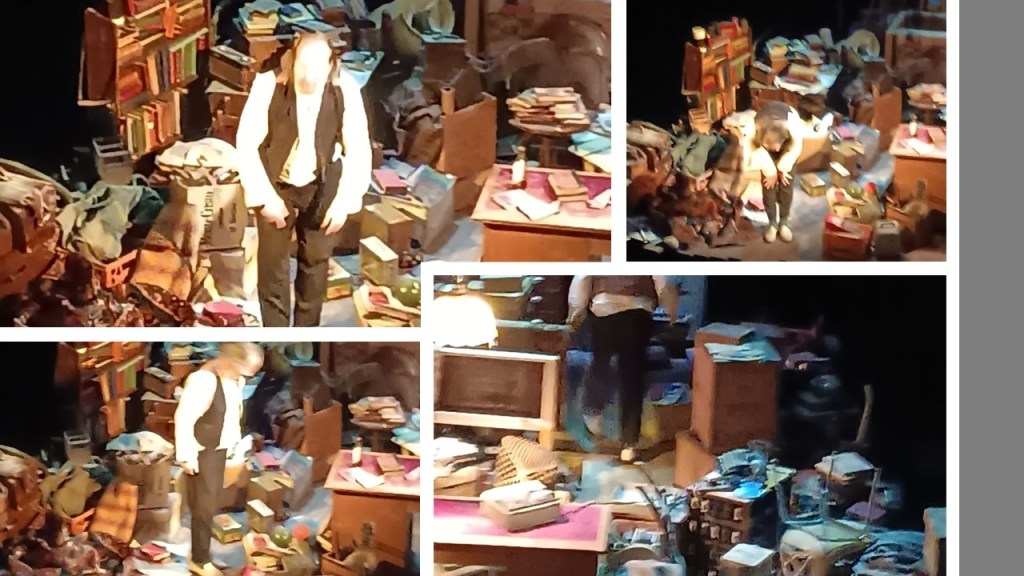

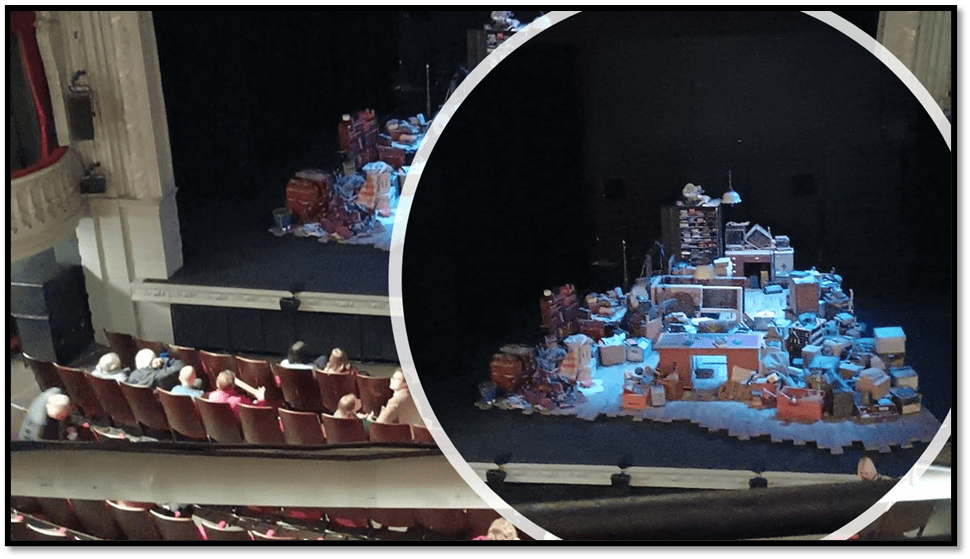

Hence the genius of this set as created by Gary Oldman – it is a ‘hoarder’s attic’ (he enters the stage by ascending into it from stairs not perceived before the play starts) and moves in pathways left between piles of kept material – for in this clutter thrown-away material is also kept materially present. Below is the set we saw before the performance: it is the very iconic recreation of hoarding and anality.

But there is another reason for the materiality of theatre. No-one goes to the theatre entirely in the mind and the heart; they have, at least, a sense of the material cost and time it takes to travel and congregate and try to be as it were a pure receiver of an impure thing – a theatre of resounding noises from the bodies assembled, coughs, and inexplicable noise from outside that context of play where only what was was intended to be heard, we feel, ought to be heard. Part of the materiality of each member of the audience’s own body plays its part in theatre. This is so even in an audience, which though comscious of trying to control evidence of their own functioning and living bodies find that control impossible. When one audience member coughs, others do, as if permitted release. It is a very anal situation.

Yet Krapp in this play is also part of its audience, for part of its time. Beckett directs him to adopt ‘listening mode’ when hearing himself from a tape made 30 years earlier, in which he in turn speaks of listening to a tape made earlier still. Oldman dramatised all this by making clear the anal style of Krapp himself – as he both tries to control emissions from his body that nevertheless constantly arise, as if uncontrollable, like coughs. I noticed too that audiences treat these as permissions to cough themselves. I think Oldman knew that as an actor – and knows that it helps to get the theatre audience to know more about the nature of the play they see and hear.

Theatre is a strange kind of ritual form wherein audiences expect to be unconscious of themselves as embodied human agents in the process. Yet we travel to them – often long distance, have bodies that get stressed and tired – and indeed did we not feel thus would lose some of the ability to respond to the dramatic and theatrical which depend on both voluntary and involuntary ways of being aware of passing time and wasted energy in the theatre. For instance, I travelled by train to York, where it was raining whilst I made my way to the theatre – at one point quite heavily. I took photographs from a similar point in my walk over the Ouse both to and from the theatre through the city. In them time had visibly passed:

Time had passed – in the ways it does by manifesting a whole theatre of sounds and sights, lights and darks but it had not passed in the way I experienced its more controlled passing in the theatre – an experience where memories of different durations are in part controlled and explained by repetitions in the script. These repetitions are, in turn, caused by the rerun of spools of tape – which have recorded a man recalling and hearing his being in all its past, passing and passed-away-ness and reliving it. A man on a tape can pretend to have organised and is continuing to order passing time:

Here, I end this reel. Box – {Pause.} = three, spool – {Pause.} – five. {Pause.} Perhaps, my best years are gone. when there was a chance of happiness. but I wouldn’t want them back. not with the fire in me now. No, I wouldn’t want them back.

[KRAPP motionless staring before him, The tape runs on in silence.}

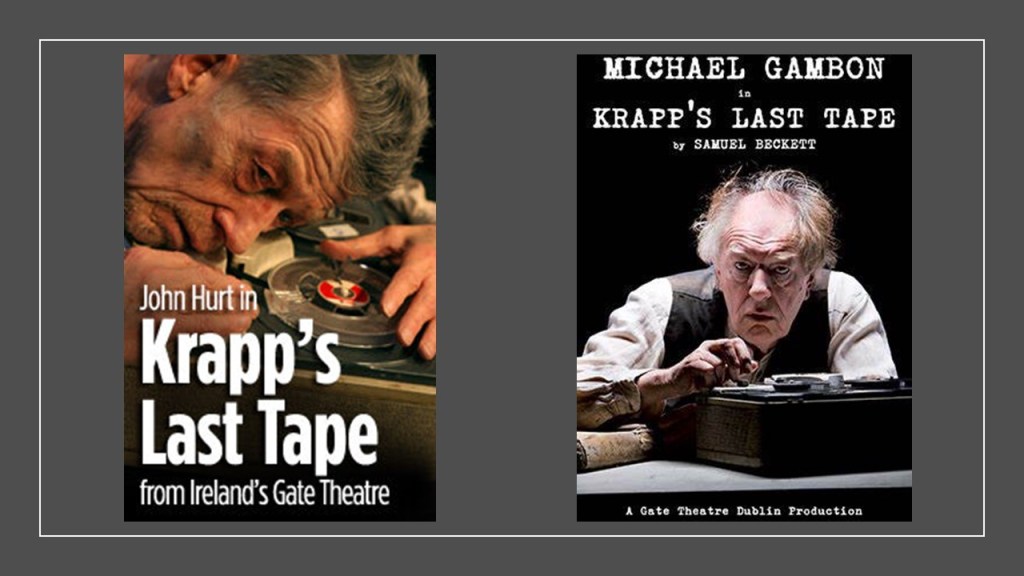

And you relive what you may not wish to as well as what you think you wish to but may find that you don’t. I often wonder why the stage direction in the play first encountered is: ‘A late evening, in the future‘. How is an actor or director to realise that direction on stage? The only way is to be forever confusing time – the sounds of clocks or of coughs – confused the more because of the sound of the Minster tolling time at the rear of the theatre. This way, we are always in a future, not as we think it might be, where we can pretend to be its master and controller. And this feature of the play has a depth in this production that I could not have guessed when I mentioned past actors of Krapp in an earlier blog (see it here), notably, at the Gate Theatre Dublin. The actors there were John Hurt and Michael Gambon.

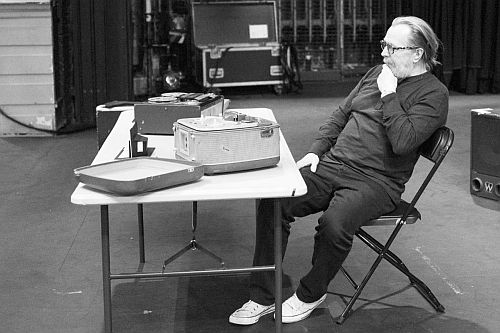

Notice above the tape-recorder featuring in both posters, for it is the same one: the property of the Gate Theatre and lent to Gary Oldman for this production in York. This says a lot about about the cycles of return and progression in this play’s repeated productions and for Oldman – the Krapp in this future – it must have resonated with the actor’s sense of allotted time and legacy, both of the earlier actors being now dead. Emilie Morin writing in the theatre programme says the recorder is the conduit to ghosts as important to Oldman as the 39 year old Krapp is to the 69 year old one, without being the same person:

From Emilie Morin (2025: 10) ‘Somewhere a man is listening to his own voice’ in York Theatre Royal Theatre Programme for Krapp’s Last Tape, 8 – 13

In this publicity shot (in the programme accompanyin Morin’s little piece), Gary Oldman look at the other star of the show – the actual tape-recorder-and-player used by John Hurt and Michael Gambon (both now have died) in productions at the Dublin Gate Theatre and were lent to Gary for this revival and revisit of this haunted play.

When the stage is slowly drawn back into darkness at the end, only the red light on the recorder shines in the dark silence, the only motion (unseen) being the tape neither playing nor recording anything. In a good review of this production, a WordPress blogger, Mariam Philpott, begins her review thus:

Silence is one of the most powerful theatre tools and it takes both a writer and actor of some caliber to really trust the effectiveness of silence in allowing the themes and meanings of a play to weigh in the air before settling on an expectant audience in their own time.[1]

That is good but silence cannot be just understood as a device in the theatre, though it has much more to do with calibrating the distinction between how audiences and actors in time experience that time, which Philpott also mentions. My sense of it was heightened for I have only ever read the play in the past and never ever seen it. It came as a shock that the beautiful prose of Beckett’s stage directions become in the theatre merely silence filled with configurations of action and inaction, motion and immobility.

James Knowlson records that the changes Becket made to his script when he produced the play in Germany were often motivated by ‘establishing a more marked contrast between on the one hand, brooding silence and immobility and , on the other, noise and rapid, purposeful activity’. He cites Beckett himself, saying he cut out “everything that interferes with the sudden shift from immobility to movement that slows this down.” [2]

Knowlson implies here though that Becket is interested only in ‘contrasting’ binary states whilst Beckett’s words suggest he is interested in contrasts of difference of pace of movement to the stasis of inaction, of words in motion and silence. All of this is about time – speed being a condition of both place and time changes. Hence, the meaning of the play is always not just about the relative time of a statement or action on stage happening and the audience taking more time to comprehend the action. I think what happens is that the audience is made to sense how time passing for them is manipulated to seem to vary by words and silence, action and inaction on the stage, all in interaction with each other. In this play, there are long silent actions and loud stasis, as well as other configurations of the basic elements: noise and action and their variants.

That is why my title picks out that repeated encounter in the past where he almost indicates active sex but not quite, spoken by the 39 year old Krapp on Spool 5 from Box 3:

We drifted in among the flags and stuck. The way they went down, sighing before the stem! {Pause.} I lay down across her with my face in her breasts and my hand on her. We lay there without moving. but under us all moved, and moved us, gently, up and own, and from side to side.

The crux of this speech is inaction that feels like action. we are ‘stuck’ but something moves. The other crux is that the word ‘moving’ employs both its senses, indicating active motion on the one hand and variants of emotion on the other – and not just passive emotion. this speech is, after all how we become ‘moved’ as an audience in this play, or at least I did. I expressed this in my title thus:

In the theatre we sit ‘there without moving. But under us all moved, and moved us, gently, up and down, and from side to side’. ‘Krapp’s Last Tape’ stuns and ‘moves’ me.

As I said earlier, being an audience – auditory or visually – means we oft pretend to be disembodied, without motion or emotion of our own: we go down like flags of reeds flattened by boats and do not feel the sexualised metaphor we have become, and suddenly words and silence, action and inaction in configuration ‘move us’ (make us feel emotion) that is felt as motion in the body -of the physical heart, of the blood it pumps around our bodies, and of the varied other autonomic nervous system responses. Up and down and side to side, we go with our eyes and our ears, and we are moved. So moved was I, I exited the theatre stunned in the Minsterley evening where light faded around me until artifice lit it again, as it always does, whilst life continues

That’s all for now

With my love

Steven xxxxxxxx.

_______________________________________________

[1] The WordPress blog site this is taken from can be followed her site on X (Twitter) @culturalcap1 or Facebook Cultural Capital Theatre Blog. Available at: https://maryamphilpottblog.wordpress.com/2025/04/21/krapps-last-tape-york-theatre-royal/

[2] James Knowlson (2021: xiv) ‘Introduction’ in J. Knowlson [ed.] The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett (volume III): Krapp’s Last Tape London, Faber & Faber Ltd, xiii – xxix.

2 thoughts on “In the theatre we sit ‘there without moving. But under us all moved, and moved us, gently, up and down, and from side to side’. ‘Krapp’s Last Tape’ stuns and ‘moves’ me.”