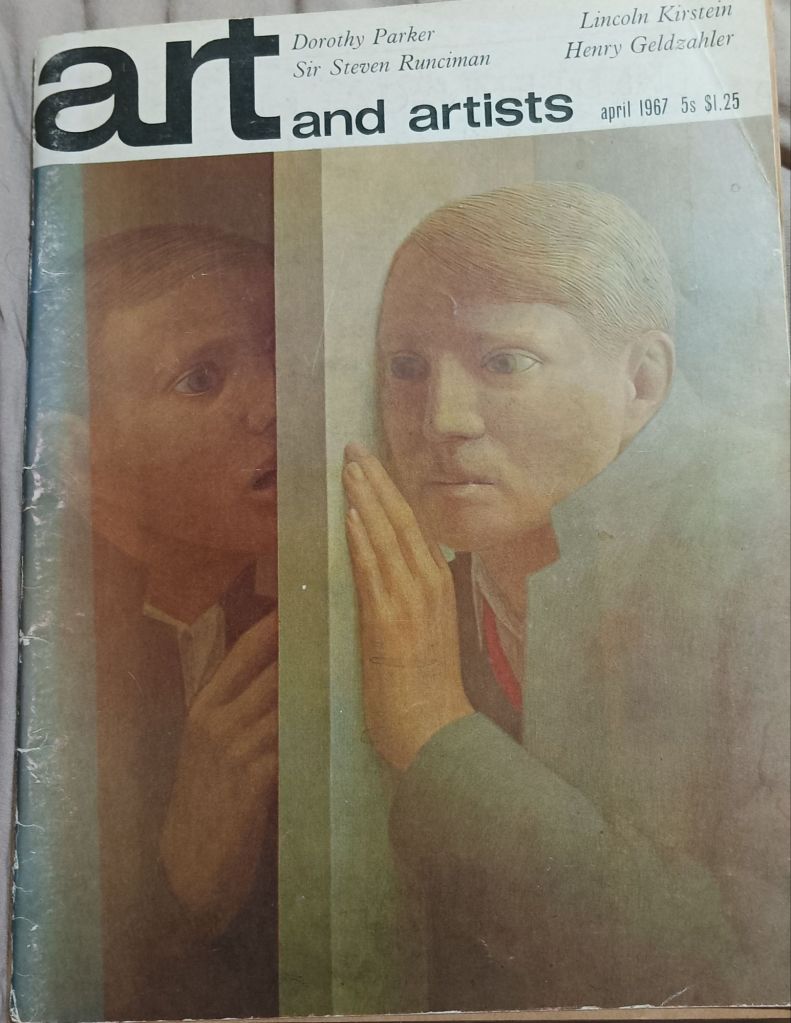

I have to admit that this blog came yet again from my cataloguing exercise. I have reached a stash of books to sort in our conservatory, They are a kind of shrine this section to my love of Byzantine Art. Nestled amongst these books was a copy of the American art magazine [pictured above] art and artists from April 1967.

My photograph of the section this magazine used to belong to in my library

I must have kept it and stored it where it is because of an essay by Sir Steven Runciman on the early reception of Byzantine Art in the medieval West. It is a stunning essay but a reprint from earlier work by that magus of the subject: the man who taught me why and how it is possible to lose your heart in Mystra in the Pelopponese.

But though I have kept this refound treasure [now number 3962 in my digital catalogue], it now graces the cabinets of my queer literature in the study. It does so because I read, maybe for the first time an original article in it by Lincoln Kerstein, pictured below:

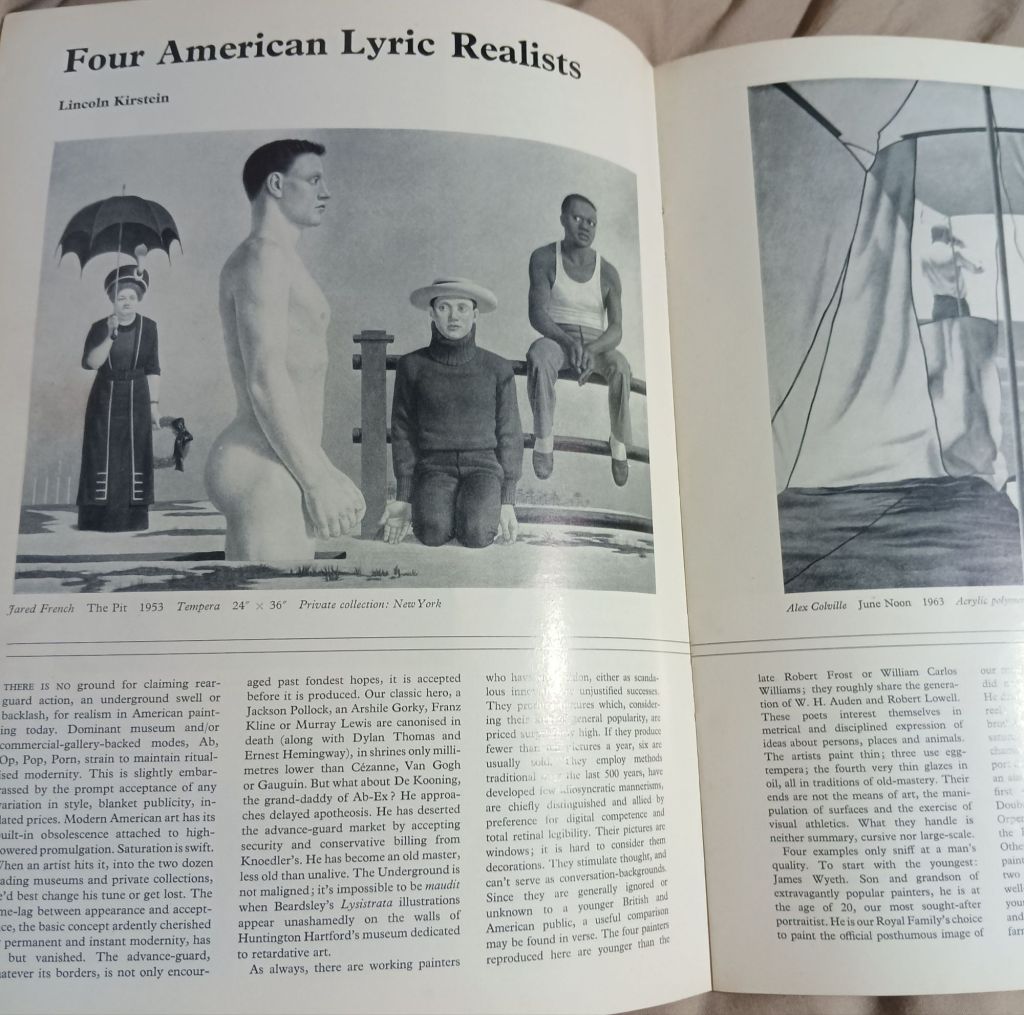

Lyric realists is an interesting attempt to name the trend in American art it honours and which it describes as, in our word, ‘niche’. He represents this tradition by works by James Wyeth, Paul Cadmus, Alex Colville, and Jared French and names them as lyric because he aligns them with the narrative lyrics of Robert Lowell, and more importantly W. H. Auden.

The main burden of Kerstein’s article is, however, an attack on the othodoxies of Modern Art of its period [how well I remember it] with its ubiquitous ‘museum and/or commercial-gallery-backed modes, Ab, Op, Pop, Porn’ that ‘strain to maintain ritualized modernity’. I was only 13 when this article emerged, but it remained the truth of American Art, and which led the world’s thinking in that area for at least another decade. His object of attack was Momism, by which he meant the Daughters of America Republican right turned into a model of bizarre anti-life motherhood, of mothers urging their sons to give up life for abstract anti- Communism in Vietnam and as a pun on the acronym MOMA (The Museum of Modern Art in New York).

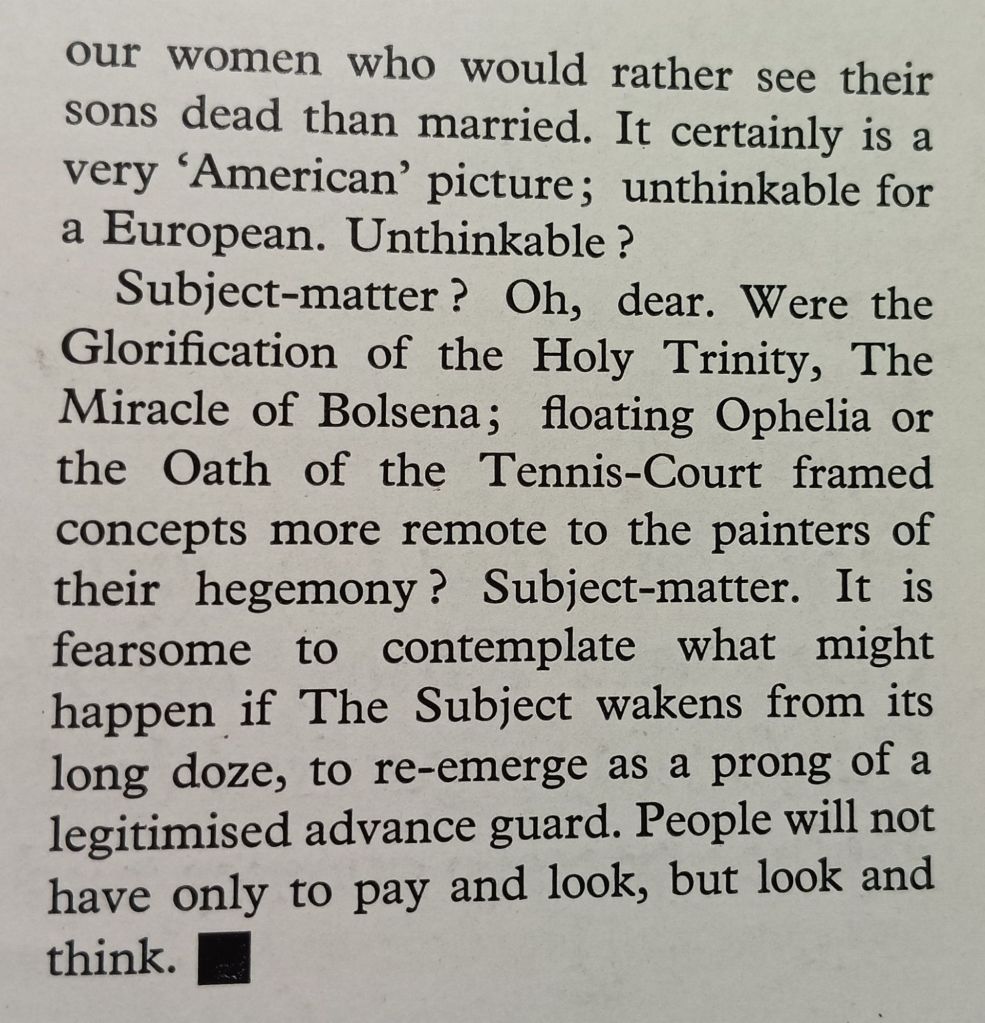

Kitstein must have represented many of us who failed to see the appeal of abstraction as an alternative to everything thought of as ‘literary’ in art: the representation of figures / persons, narratives and symbolic or iconographic prompts to thought. In short he meant the art that had a ‘subject matter’. Hence, his final paragraph, which takes off after his attack on Momism: ‘moms’ or –

Lots of artists in the UK too fell foul of the distrust of ‘subject matter’ in favour of an art fulfilled only in the design of surface features of the framed artwork praised by Clement Greenberg and whose master was, Greenberg, said, Jackson Pollock. In England the victims were great painters, such as Keith Vaughan and most sadly John Minton, queer men in the UK with a story to tell and the limits of humanity to portray in their figurative and narrative art. But above all queer artists are required to think about the basic ingredients of narrative and character: desire and its fulfilment or otherwise in the context of hegemonic heteronormativity that had alienated them and made their lives unthinkable.

One example from the article is James Wyeth, the grandson and son of revered American painters. Kerstein poses the question of the example from Wyeth: a portrait he says of the mechanic who serviced Wyeth’s sports car engine and saw it as preferable to being drafted into the US Army and being sent to Vietnam. However, from the picture alone given in the article, The Draft Age is a complex picture of early twentieth century masculinity about which American painters might feel all kinds of nuance, positive and negative but certainly mixed up with complex bisexual desire:

The British examples I give are of queer men, as Kerstein does of his Americans, without, as I do, any vulgar breaching of their closeted framing. However, queerly enough, Kirstein’s choices are successful examples of narrative and figurative art that Lincoln lauds and who were also queer men [men fluid in their sexualities and not looking for any one label too soon] who were well known to him personally and bisexually. I will confine myself to three of his chosen heroes. He describes their tendency in an early part of his essay shown below in my photograph of it:

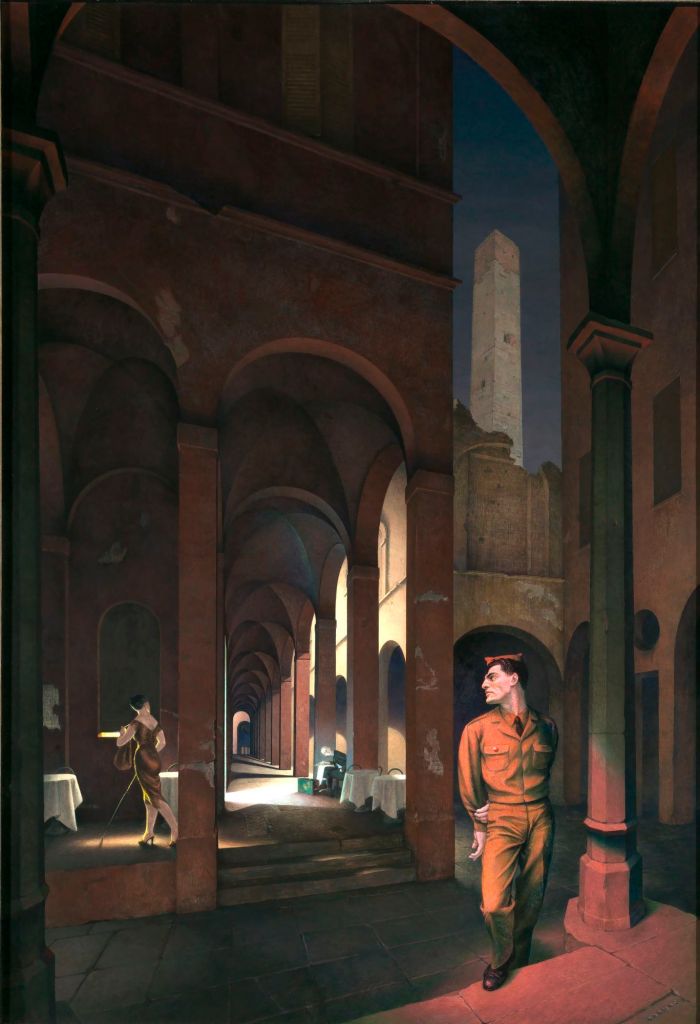

I will look a little at the paintings Kirstein analyses later, but first, let’s look at a painting that he has [in 1967] provided us with a black and white reproduction in the article – only four were chosen. This one alone he does not in his article vetbally comment upon. As I thought about the possible reasons for that, I was lead finally to believe that Kirstein did not comment because it was not possible to be true to this painting except by making his article explicit about the layers of suppressed and networked sexualities in it, though some are in hiding in plain sight. It is Paul Cadmus’ Night In Bologna.

It is a great painting to use to illustrate at least one idea of Cadmus’ work – that of aping the settings and materials of classic Italian Renaissance Art, even down to the fraying stucco on his beautifully reproduced Bolognese pilasters and perspectival corridors. Cadmus even used egg tempera paint to capture an early Renaissance feel, though the issue of perspective- how the point of view changes the form ( but also as we shall see, the meaning) of what is seen on a painting’s surface.

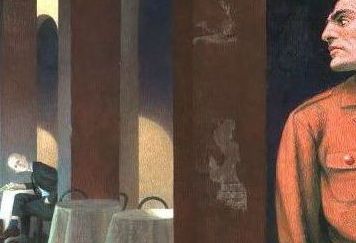

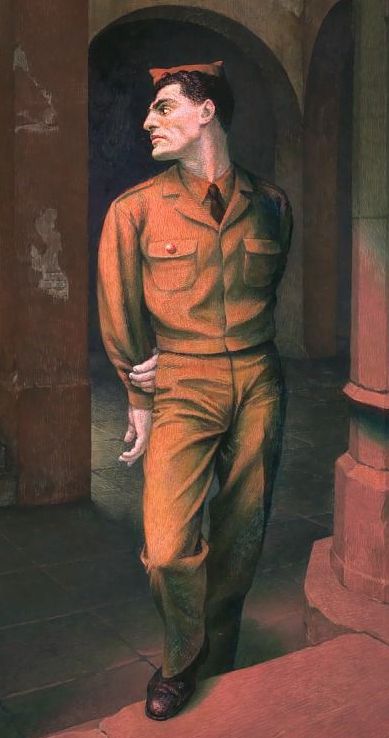

Any viewer’s gaze will almost immediately rest, in viewing this painting, on the figure of the hyper-masculine, in body at least, American G.I. However, he does not return our gaze, which seems directed back into the depth of this townscape onto a slim young woman serving tables in the cafeteria behind him. Or is the actual goal of his pwrfprmative gazing.

We only ask this because the painting demands we recreate possible narratives, and nothing about the young woman in its mid background, the very stereotype of female form from the period, indicates she is showing any visual interest in the soldier. She appears to be looking back at a customer inside or in the arched corridor outside the cafeteria. A painting like this makes us look further, for it is possible the person she looks towards is a customer drawn in such fine detail, we only latterly see him. Let us then draw close:

What we now see is a triangulated possible drama of the gaze of which the apex view is a middle-aged gentleman. He is craning his neck to perhaps catch the delightful waitress’ eye. Or is he. Let’s pull in closer still:

Suddenly we see that his gaze could equally be being drawn by a non-committal sideways glance from the GI, who is equally aware that he can be not only the subject of his own desirous longing but also the object of another man’s desire, and valued, for that reason, even in terms of monetary values. And then return – pull back as it were – and examine the pose of the soldier, for it is a pose stereotypically sexualised. It is in the manner of the classical Greek, so much copied in the Renaissance, contrapposto stance, but it allows the thrust of the groin to be emphasised in ever so sexy Baroque folds in his army regulations trousers.

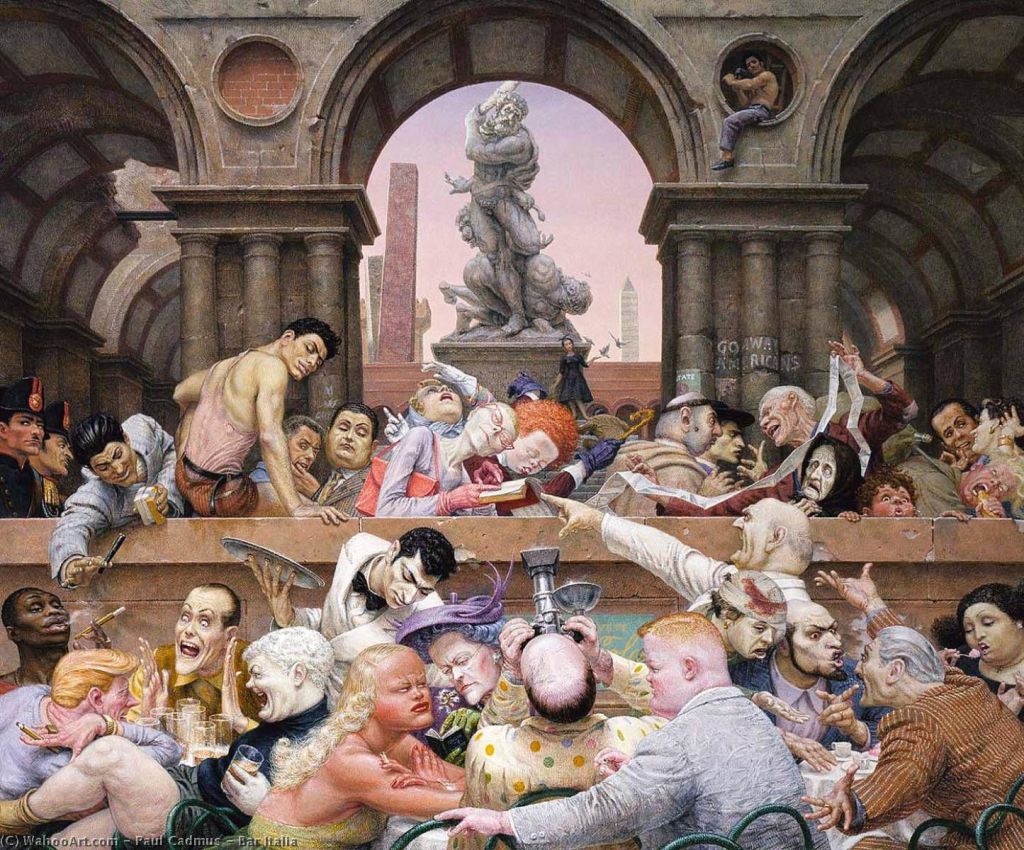

I hope I make the point here that ‘subject-matter’ is inexhaustible to the eye if you allow it to be and do not reduce it to abstract interacting surface forms. This is the point of another painting by Cadmus that Kirstein does discuss, though only to say that it shows Italy as Henry James both loved and hated it, a point we don’t quite get unless we are sensitive to the knowledge certainly held by the PaJaMa Group [more of that later] that James used Italy to explore his closet sexuality; in both Roderick Hudson [see my blog at this link] and The Portrait of a Lady.

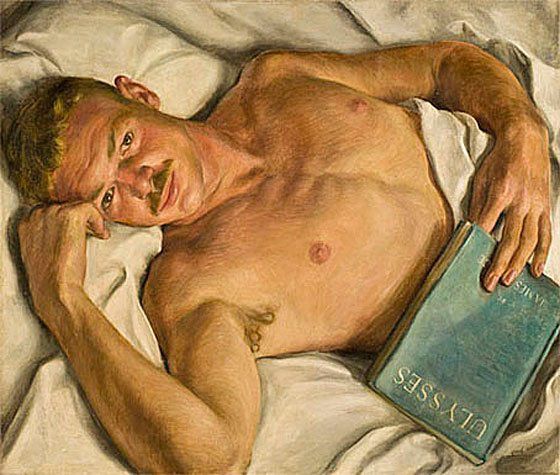

Cadmus’ painting, Bar Italia, is one wherein Mussolini rubs shoulders with American tourists and types and settings straight out of a queered vision of Raphael but turned into a raucous Harlem bar; and it is just a delight. But as Kerstein states, Cadmus was in his eighties when this article was written. The article turns instead to Jared French, in reality Cadmus’ male lover, though conveniently married to Margaret French, the photographer and artist. Always together, Paul Cadmus, Jared, and Margaret French were the three parts of the PaJaMa group of artists. Their work was often coded and could inhabit closets as well as gallery walls (if these are not the same thing!). However, desire spoke through it, as in the portrait by Cadmus below of his love of the literary modernist in Jared, who is reading James Joyce’s Ulysses.

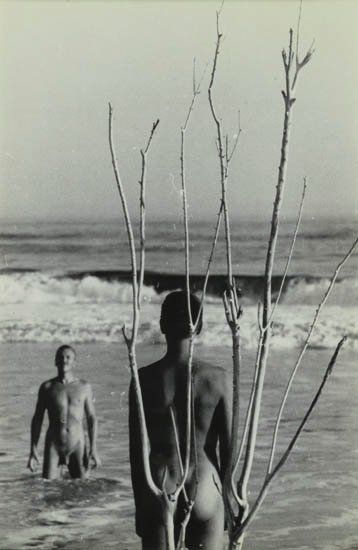

The book is rather shadowed by the come-to-bed eyes. Had their photographic art, mainly fired by Margaret, been available to us earlier – they made cards of them to give away at Fire Island queer parties – the code of their paintings might have been easier to break. Consider this full frontal Fire Island beauty of Margaret’s:

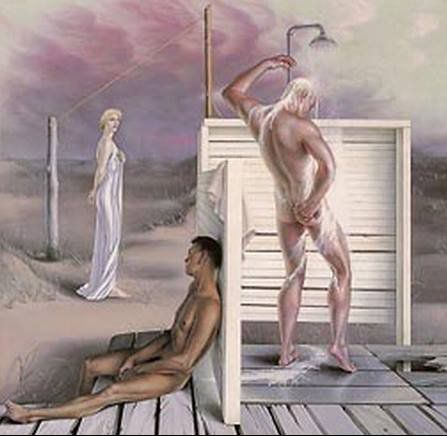

These photographs are clearly articulations of desire through empathetic exchanges of the gaze and sex/gender boundary crossing. It makes the painting below by Jared easier to read, if still mysterious with regard to what is an interior or exterior image of our desire and identification. The subject of these paintings was often narcissism as the subject/object of thought.

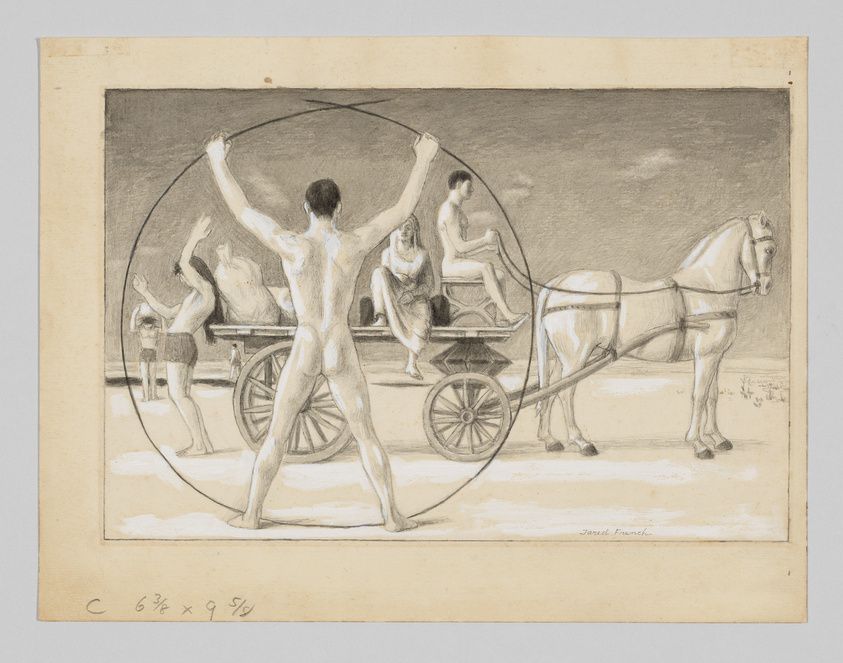

In some drawings by Jared, the model of man in Renaissance painting is evoked, but in rear view only, for in part Jared wants to show his audience their reflected and absurd prudery at the sight of the frontal naked male – more so at his period than the frontal naked female – was.

See how the dimensions of man are sexualised not by homest display but prudery. This is why Jared has Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man turn his back on us to show himself off only to a cart of passing tourists, driven by his naked self.

And finally, then, to the Jared French painting Kirstein both shows in black and white but also talks about most, though under the title he knew it as, The Pit. It is nowadays known as The Double. The second title helps us to see the narcissist element and that the clothed and naked young white men are identical other than for clothes and stance.

However, it hides the dreadful and awesome moral commentary that Kirstein finds in the painting.

Look first at the coding of the picture, particularly the hiding of the naked young man’s genitals to both his clothed conservative other self and another by his huge manly hands. That other who is not himself is coded as such by his skin colour. The mother in funereal black with the wreath Kirstein argues is Momish America, preferring a dead son in a pit to one who gives himself, even ocularly, to other men and mght prefer to be nude when alive with others than naked and alone in the pit of death.

It is a most wonderful painting, but if you can compare Kirstein’s description in his coded style in the magazine with mine, you woulf agree. In a sense, the descriptions are the same, but his is still clothed in the shame of his age and period. If you want me to copy his description, I will surely do so if you ask me. However, now I am travelling on my way to York.

Bye for now.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxx