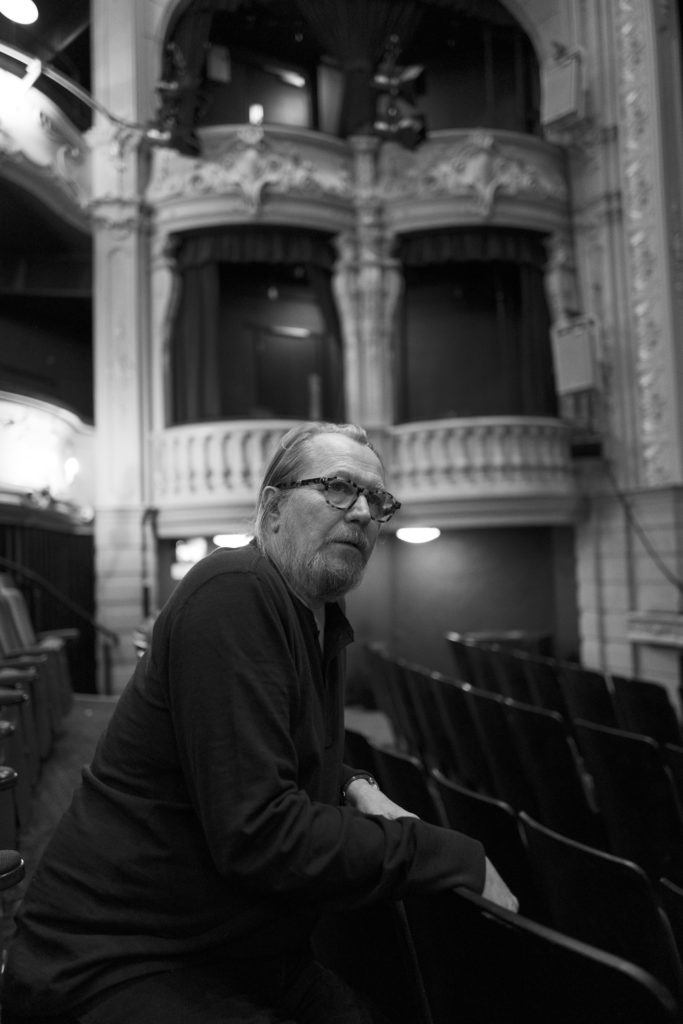

Gary Oldman viewing the auditorium of the York Theatre Royal, on whose stage he opened performance last night for the first time of the play by Samuel Beckett, under his own direction, Krapp’s Last Tape. I see it at 7.30 p.m. on 22nd April. Photograph from theatre website: see https://www.yorktheatreroyal.co.uk/latest/gary-oldman-stars-in-samuel-becketts-krapps-last-tape-at-york-theatre-royal/

I will see Gary Oldman performing, under his own direction, Samuel Beckett’s brief one-act play, Krapp’s Last Tape next week (7.30 p.m. on 22nd April) at York Theatre Royal. This play is, in terms of Becket’s oeuvre as iconic as King Lear is in Shakespeare’s oeuvre. The role of Krapp moreover is thought to be as challenging and hence an actorly aspirational goal as that of King Lear himself – or herself or themselves (now we know that Glenda Jackson completed her ambition to play it before her death, opening up the sex/gender conundrum in the play). Krapp’s Last Tape itself has such a conundrum too, since like Lear, the character has repetitive visions of the role of women in his life that are as deeply sexualised (and misogynistic) as Lear’s, and as based on stereotypes. The well known critic of Beckett, and correspondent of the playwright, James Knowlson, confirmed as he saw it – for Beckett did not contradict Knowlson’s articulation of these themes in writing to Beckett letters that received fulsome answers – that the themes of this play were ‘solitude, light and darkness, and woman’.(1) Again these are commonly now cited as themes though usually configured in relationship to each other.

It is difficult to preview Beckett, for contrary to belief, as Knowlson reports, Beckett was not averse to altering ‘the words themselves as he directed his plays’. It is not true hence ‘that the words are sacrosanct to him’, although Knowlson shows the though when Beckett directed Krapp’s Last Tape (as Das letze Band) in the 1969 Schiller-Theater Werkstatt Production (the play was first performed in English at the Royal Court Theatre in October 1958) the changes were largely cuts – whether in speech and/or stage directions – but that when Beckett did make changes (including omissions), even minor ones, they were very significant to the direction each production specifically aimed for. Sometimes there were even based on the actor playing Krapp, for the play was originally written for the voice of Patrick Magee, and that some later production changes followed the visible, heard and intuited character of other actors who brought themselves to the role. There is therefore plenty of invitation here for an actor-director to direct stage setting, actorly delivery and voice, indeed in variant voices for we hear Krapp speaking on replayed audio-tapes supposedly from at lest 30 years before the setting of the play, in very different voices – and perhaps words and contingent actions. None of Oldman’s intentions have I been able to read about, and early notices of the play in rehearsal have NOT given a great deal away.

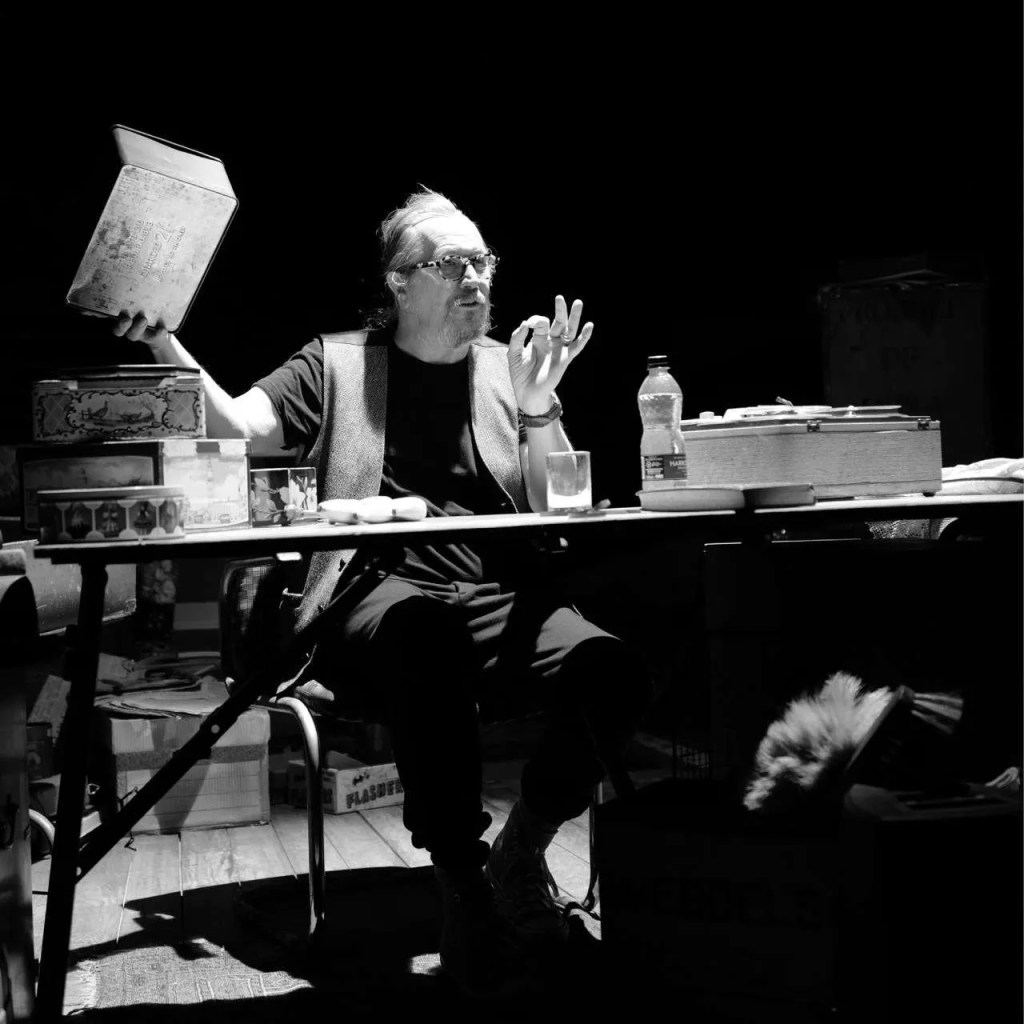

This still of Gary Oldman rehearsing his role gives little away about the final staging and acting in the play but it is a delight to see

James Knowlson has provided Beckett fans with the closely written production notes of Beckettas a director (in facsimile and transcription) in his book and Beckett clearly shows how much changes mattered in his attempts to convey meaning, tone and attitude to the act of seeking meaning in the text and reported action, He also pieces together a revised text in which some changes challenge readings made by literary critics. Take, for instance, Lois Gordon, offering a ‘New Reading’ of the play in 1990. Like most literary critics, she takes words embedded in text seriously – even stage directions I take it from some of Beckett’s words that she chooses to quote. She deliberately acts as if plays were ultimately for reading not seeing and hearing in a theatre, expressing her point thus, although Gordon should not require me to say that ‘deciphering a dream’ is not very like ‘reading a poem’. Moreover reading visual detail from costuming, lighting and sound effects cannot be done entirely from stage directions:

Reading the play is like reading a poem or deciphering a dream, with every detail integral to the meaning, particularly costuming, lighting, sound effects, and gestures. (2)

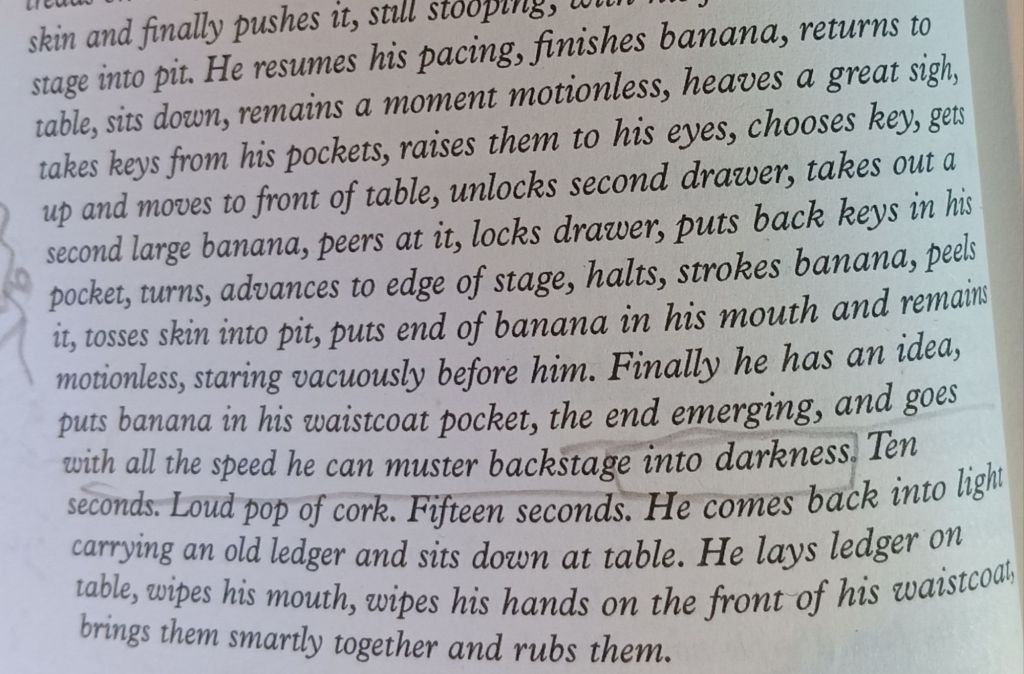

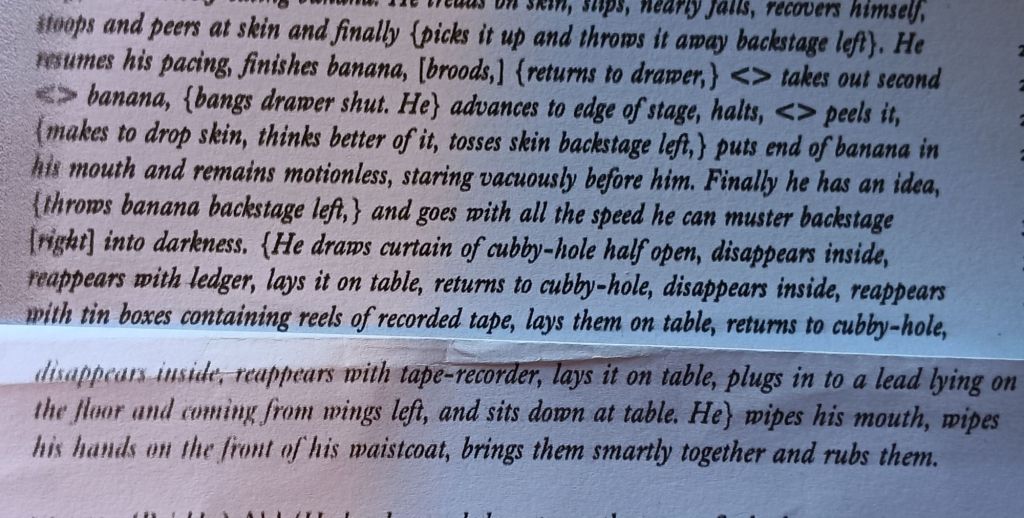

With this any scholar of theatre might agree but it leaves so little for the actor-director to add to the text. To reproduce Beckett’s own practice is impossible without realising that Knowlson has truly proven by revisding the original text of the play as it would be following the 1969 German production. See these two versions of the same stage direction from the Standard Faber and the Knowlson text below:

The Standard Faber text

The Knowlson revision used on the 1969 production

Of course we are not comparing like with like but the changes to the words based on Becket’s production of his own play means that if in a Becket play it is true that ‘every detail’ is ‘ integral to the meaning, particularly costuming, lighting, sound effects, and gestures’ unless we accept, as I do that a production can freely change the configurations of details precisely to show changes in the nuance of meaning required in each production based on lots of factors, including the contribution of the actor playing the older Krapp and also the younger ones recorded, in the fiction of the play, on spools of tape-recordings. There are obvious details. The drawers containing the banas are no longer locked and therefore require no keys, a piece of business Gordon aligns with the bananas to indicate the onanastic in Krapp’s character. In 1969, there were no keys and the business with bananas was much reduced and changed in tenore, reducing its clown-like character a little. The set was used more specifically with additions of motion to the right and left of stage as well as movement backwards and forwards from a central pool of stagelight. Lighting too then takes more nuanced meaning in 1969 to add to the mass of references to that contrast in the play – in spoken text and staging directions. This includes some favourites of mine from the standard printing of the Faber & Faber text, as here, where Krapp: ‘goes with all the speed he can muster backstage into darkness’. In the 1969 Knowlson text this becomes ‘goes with all the speed he can muster backstage [right] into darkness’. What is added by that right move, especially since the furnishing on stage has changed and been added to. Instead of ‘darkness’ alone hiding the business Krapp wants to be secret, he hides it in a reall structure built on stage: ‘a cubby-hole’.

No doubt the differences may strike you as trivial, but matters if we agree with Gordon that when elder Krapp 9at 9 years of age) listens to his 39 year old self on the tape saying that it was “clear to me at last that the dark I have always struggled to keep under is in reality my most -” that it is at this ‘point the audience is compelled to ask: “my most – what?” (3) They are thus compelled because the contrast of dark and light resonates throughout the play. Knowlso believes that is because the play works on a paradigm based on the dualism, two binary opposites straining for unity (including good and evil) in Manichean thought. Whilst it appears Becket did not discourage Knowlson following that path to find the playwright’s meamning, he did say to him: “Wild stuff, though you may use”. (4)

For me, all I need to do in this blog is to set myself the task of, whilst enjoying Gary Oldman as an exquisite actor, seeing if he makes changes to text or to self, stage, set or costume direction or to the words spoken – even by omission -that might show he is straining to become a new version of the fragmented characters that combine as Krapp. And if so< i want to try and understand why. For the choice of taking on this play is the belief that you have something significant to add to its interpretation or its extension in theatrical experience – taking on board effects of meaning, feeling, sense response (visual or auditory but perhaps also in terms of the feeling of touching on something new about aging and mortality in the play).

I hope I will be back to say more next week.

Bye for now

Love

Steven xxxxxx

___________________________________________________

(1) James Knowlson (2021: xx f.) ‘Introduction’ in J. Knowlson [ed.] The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beket (volume III): Krapp’s Last Tape London, Faber & Faber Ltd, xiii – xxix.

(2) Gordon, L.G. (1990: 100). Krapp’s Last Tape: A New Reading. The Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, 4, 97 – 110. Available as pdf: https://www.bing.com/search?pglt=299&q=Lois+Gordon+(1990%3A+100)+%27Krapp%27s+Last+Tape%3A+A+New+Reading%27+in&cvid=5dfbf93993124f758de795b67c3eab1e&gs_lcrp=EgRlZGdlKgYIABBFGDkyBggAEEUYOdIBBzk1MGowajGoAgCwAgA&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=EDGEDSE

(3) ibid: 102

(4) Knowlson, op.cit: xxii

One thought on “Samuel Beckett was as meticulous about writing his stage directions as he was in writing poetic prose, and contingent character-based exclamations, of the monologues and dialogues spoken on the stage. How radically will Gary Oldman dare, if at all, to rewrite both the stage directions and words of Beckett’s spoken by him as ‘Krapp’.”