Good theatre is a shared experience but what is shared can only be decided by negotiation of our responsibility to all of its collaborators – writers, directorial staff, actors, the theatre and the audience. J.B. Priestley has his strange inspector (of what we ask) say in ‘An Inspector Calls‘: “you see we have to share something. If there’s nothing else, we’ll have to share our guilt”. A funny thing happened to me when I went to see Stephen Daldry’s production at the Sunderland Empire on 8th April 2024.

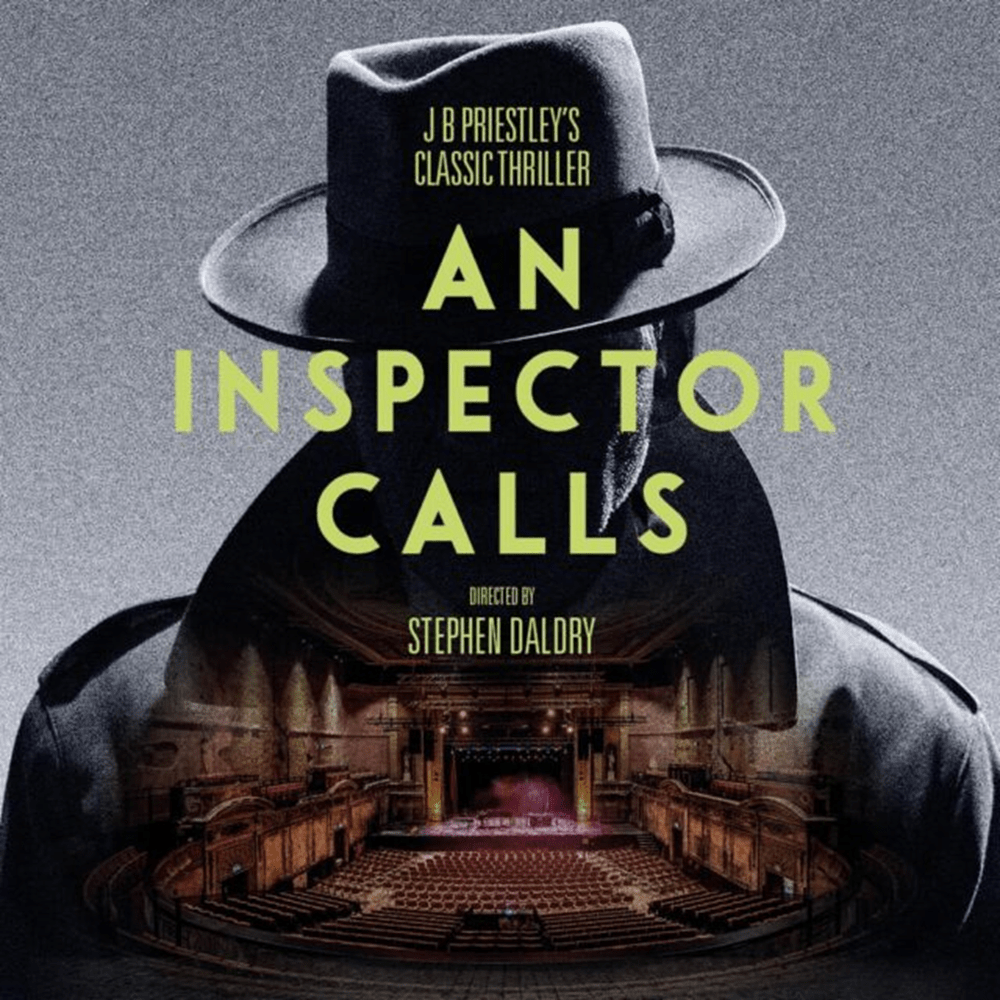

Have you ever thought of the strange collaboration of the manufacture of meaningful experience in the theatre, which applies even if all you think theatre does is offer ‘entertainment’? It took an extreme occurrence for me to understand that. The poster for that production ought to have forewarned me of this. It shows as you see above the torso of a detective inspector, his head shadowed by a conventional trilby and high coat collar so that this head is a dark secret.

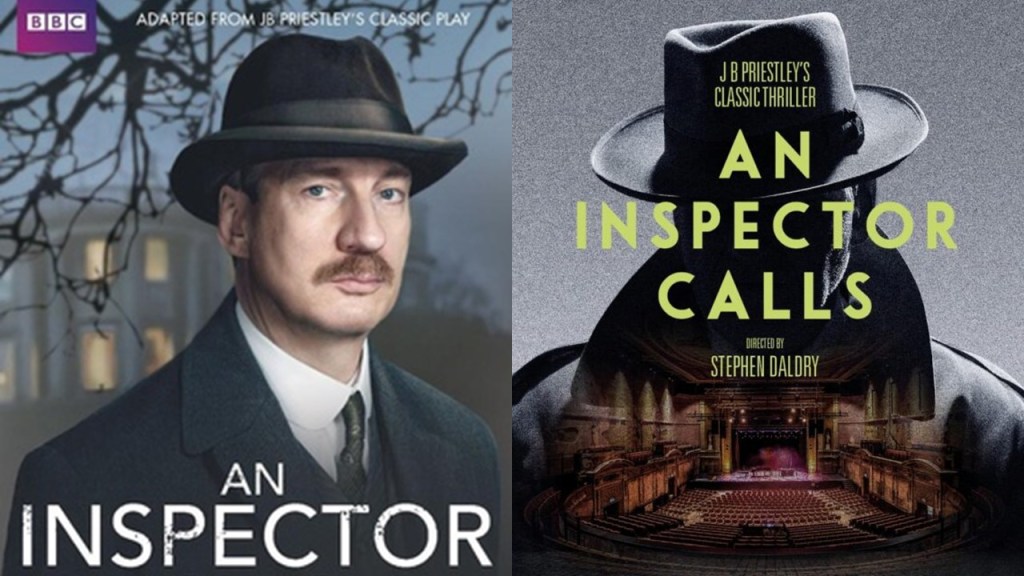

His upper body has become, as it were, a frame for the image of an ‘inner’ theatre space – a rather lavish one, as if something about this drama needed to be based on an agreement between cast, crew and audience that what we are to experience is a drama which is somewhat of an interior thing, rather than an external show only. Compare the advertising poster with that for the BBC production of a verson of the play which preceded it, on the left of the collage below.

The BBC poster shows a lit country house in the distance, between us and which stands a male with the characteristics of a detective from a country house murder thriller. Both house and character are part of the stock stereotypes of that later genre. The production indeed used this stereotypical masking theatrical genre in order to subvert the genre it pretends to be: for it is only at the end of the play that the ‘inspector’ is revealed as not a police operative at all but some kind of ethical agent of uncertain, and perhaps supernatural, origin. But the play never uses the elements of its set or characters as symbols of an interiorised experience of moral experience.

I love this rather conventionally structured play. It is almost the very model of a ‘well-made play‘, which was the ideal of the playwright of Priestley’s day. The characters at the end emphasise this, recalling at the denouement of the play, its opening circumstances, rounding them into a conscious theme of the play as a whole. There, in Act 3, this exchange occurs which reflects on the structuring of the play’s events around that theme by Priestley in his original text, and the means by which he urges us to reflect on it:

Birling: …. I’ve learnt plenty tonight. And you don’t want me to tell you what I’ve learnt, I hope. When I look back on tonight – when I think of what I was feeling when the five of us sat down to dinner at that table-

Eric: (cutting in) Yes, and do you remember what you said to Gerald and me after dinner, when you were

feeling so pleased with yourself? You told us that a man has to make his own way, look after himself and mind his

own business, and that we weren’t to take any notice of these cranks who tell us that everybody has to look after

everybody else, as if we were all mixed up together. Do you remember? Yes – and then one of those cranks walked

in – the Inspector. (laughs bitterly.) I didn’t notice you told him that it’s every man for himself.Sheila: (sharply attentive) Is that when the Inspector came, just after father had said that?

Eric: Yes. What of it?

Mrs Birling: Now what’s the matter, Sheila?

Sheila: (slowly) It’s queer – very queer – ( she looks at them reflectively.)

The debate in the play against ‘cranks’, amongst whom the Inspector whose declared name is Goole (or is it Ghoul!!!) will be numbered: in Birling’s words he is: ‘Probably a crank or some sort of socialist‘. At this very moment, the haute bourgeoisie, represented by Mr Birling, and the minor landed aristocracy, represented by Gerald, son of a country estate dowager, begin to knit together, as those in control in the world of the play often do – at the golf-course, in the halls of august institutions they control (even fine shops), or in ‘charitable’ endeavours – in order to marginalise the conscience that the Inspector has forced each member to inspect in themselves at an assembled engagement celebration between the families and classes represented at it. The call to ‘remember’ and the act of reflecting on how the Inspector seemed to be ‘called’ up, as a supernatural being ot other ‘queer’ phenomenon, is ‘called up’ by the invocation of principles of self-interest against a kind of communalism – a respect of each other’s rights and responsibilities with regard to each other, irrespective of class, status and income divides.

The ‘talk’ recalled an earlier ‘lecture’ to his children in Act 1 as the engagement celebration ends, which was after all nearing its end as the play begins, where Birling sets himself against the ‘silly talk’ of cranks and others (the events reflected upon are those between 1910 and 1912 roughly and refer not just to socialists but those who both warn against the possibility of war with Germany, those who oppose war entirely, and the even more ‘wild talk’ of ‘possible labour trouble’ just because the ‘miners came out on strike (he refers to the real Miner’s strikes of 1911). As he urges his children to remember, that which they actually bring up in Act 3 as cited above, he mentions the writers who are the kind of cranks he means:

I’m talking too much. But you youngsters just remember what I Said. We can’t let these Bernard Shaws and H.G.Wellses do all the talking. We hard-headed practical business men must say something sometime. And we don’t guess – we’ve had experience – and we know.

The memory laid down here is echoed throughout the play in discussions about who is responsible for whom in the world and to what degree we are required by some principle of our human being to share anything – whether compassion or more radically power and wealth, without the need of revolution or its threat to spur us on (a revolution men like Shaw and Wells had in the period the play is set in set themselves to avert by urging social reform). Priestley never consciously aligns himself with the Fabian tendency of Shaw and Wells but he certainly reinforces their urgency, in 1945, just as another World War has ended. That is why the Inspector says, in a speech I quoted in my title: ‘ “you see we have to share something. If there’s nothing else, we’ll have to share our guilt”. Priestley sets out here that sharing ‘guilt’ is the alternative to active intervention to improve the lives of others who are scarred by the brutal divisions and inequalities of a society that will not learn to share its resources in some better way.

So much for the play I knew (for now anyway), although I had not then reread it, as I have since I visited the Sunderland Empire for the 2.30 p.m. matinee performance on the 8th April 2025. But therein hangs my tale, for this blog needs to share the experience of a theatre trip that went very wrong for me and my reflection on that wrongness. That’s because my husband, Geoff, and I abandoned it, with me in some distress of feeling; probably just as Inspector Goole was about to enter the stage. But to know why that happened I need to tell the tale and try to tease out its relationship to my later reflections on the purpose of theatre. Geoff and I had rather mis-timed our journey, and we got to the theatre with only ten minutes to spare before curtain up. We sat in our seats and gazed at the stage (those the photographs below are by a friend, Joanne, who saw the play the evening before and had been delighted by it, as I thought she would be):

Of course, given our timing, more of the audience was present than shows in Joanne’s photograph, and we struggled to our seats. These were seats C1 & C2 in the Dress Circle – pressed against a wall behind which were a set of enclosed steps. I noticed that because I saw a small gap that would get me to the stairs if I needed them urgently: older men with enlarged prostrates have to eye such things out. Below me in The Dress Circle, I watched a small sub-drama. The seats below us on rows A and B were empty and a gentleman was plotting with his little group in the restricted view seats in the circle leading towards the theatre boxes to get his party, led by himself of course, into the seats on Row A if they remained empty once the house lights went down.

This reminder of the physicality of the audience guarding its own self-interests as individuals and sub-groups struck me as interesting. Still, I was looking forward to the play, and my interest was entirely in the group psychology of the sifuation. However, it was soon clear the house lights were not going to go down. The curtain remained with its skewed folds still showing. 2.30 p.m. came and went just after theatre-ushers showed printed notices instructing audience members to now silence their mobiles phones

It was then I noticed how many uniformed schoolchild there were in the audience, as if every school in Sunderland had descended on the theatre in an attempt to fire up the GCSE English results for here was an involuntary audience, intent on testing the projection of both its power and, no doubt, vulnerability. But this was a smart audience too; collaboratively, heavens knows how, finding enough harmony to, every few minutes as we waited and waited, start a ripple of applause that would grow steadily into crescendo, accompanied towards its end with loud stamping of many feet. Four or five instances of that past, a group of another final year students filed into the front rows of the stalls. It was now about 2.37 p.m., but still, we waited with numerous role-calls of that faux choric applause and stamping.

Now it was 2.44 and , as if to carry the repertoire of usual responses allotted to an audience rendered passive by.the conventions of nineteenth-century theatre, into more domains of insistent self-parody, the same youths loudly and ‘theatrically’ made ‘shush’ noises. It parodied, I would say, the responses the crowd’s former behaviour had intended to arouse in non-participants in it. I say it was loud, but it started softly, increasing in volume and frequency as taken up by the participants as if a new choice strophe.

In my title, I asserted, though I am less sure of myself than I sound, that:

Good theatre is a shared experience, but what is shared can only be decided by negotiation of our responsibility to all of its collaborators – writers, directorial staff, actors, the theatre and the audience.

I got to that conclusion, I think by trying hard to rationalise the disturbance caused, in me at least, by those events. Here, a young audience was chorically play-acting roles assigned to passive audiences (clapping, stamping, shushing) out of context but doing so in order to manifest its sense of frustration and to assert control where none otherwise existed. As the audience performance mounted in volume and felt energy, the role was being made much more excitedly addictive. Maybe fron-of-housr guessed that too, because at 2.50 they signaled the start of the show and the lights went down.

The first noticeable event after that was the moment when the group I mentioned earlier as eyeing the empty seats at the front of the Dress Circle saw their chance and moved into them, momently blocking our view in doing so. The show had started but started strangely, not in a way recognisable to the schools’ audience as the start of a play. Hence, their heightened behaviour continued – now as giggles and cat-calls at the events they could not interpret on the dark stage area before the still unraised curtain. The red proscenium curtain was still shut, and a child-actor entered in front of using a torch to light his way, making patterns of light with his torch on the red velveteen .

Joined by other child actors, the first of them seemed to be intent on querying the nature of the curtain and attempting to see behind it by burying underneath its weigh, which weight you felt. That was still going on when the curtain raised as if in response. As I retrospect, I think the purpose of this prelude was to emphasise the artifice of theatre, remind us we are at a play and to suggest that what we are about to see lies within and beyond various ‘covers’, curtains and disguises; pointing to a reality more interior than exterior, a shadow-play with symbols that both mask their reality whilst they manifest it, for that is the case inside the lives of all the Birling family members. The young audience felt all this meta-stuff rather ludicrous and showed their opinion.

The scene revealed behind the curtain was almost surreal. At the midpoint of the proscenium space was an elevated Edwardian house of fairly grand proportions, or so it seemed. In front of it was a cobbled street with drains, a red telephone kiosk and a cityscape in the background representing the fictional Brumley, a ‘Northern Midlands’ town or city in which the suburban-living Birlings had the raw materisls of their wealth.

There was fog, and it was actually raining on stage, heavily. On the streets surrounding the Birling house was a dumb-show of events centering around a woman with a difficult and impoverished life.

However, this external show served mainly and to muffle the dialogue of the play spoken inside the house facade, the figures speaking just seeable as giants, as it were, in the house’s actual diminutive interior through its lighted windows. When placed as a container and, in the event, next to live human actors who squeezed out of what turned out to be doors only a half of each actor’s natural height, it wax clear that our belief that the house on the set was not a large house, accept as interpreted (as audiences are so willing to do) as seen from a low and distant perspective, but as a kind of enlarged and realistic doll’s house. Again, the point seemed to be to force our attention onto the artifice of bourgeois life, whispering its triumphs (like this engagement between two Brumley dynasties).

The version is much shorter than the play, but I caught some main pieces of dialogue, by straining (intent still on collaborating with the fiction of the play that demanded loud brash socially confident voices of a vulgar bourgeois family to be heard as whispers locked inside their own money-conscious interior but somehow trapped and diminished by it. For these characters, even in a socio-realist productions, are really trapped and diminished beings for several reasons. Their big psychosocial events are traps, particularly for women, as Mrs Birling, once the daughter of aristocrats, admits in her marriage advice to her daughter, Sheila, as she urges her not to question Gerald, her husband-to-be, as to his whereabouts too much before or after marriage:

Mrs Birling: Now, Sheila, don’t tease him. When you’re married you’ll realize that men with important

work to do sometimes have to spend nearly all their time and energy on their business. You’ll have to get used to

that, just as I had.

As the play progresses , we will discover that underlying the absence from Sheila about which she ‘teases’ Gerald was, in fact, his first rather dramatic infidelity to her, in ‘keeping’ a working-class woman as a socially uncomplicated source, for him but not her, of sexual adventure and pretend ‘charity’ for her poverty. We have, therefore, to hear those words to understand the play’s themes and the significance of its plot and characters. I remember looking at my husband then, whose hearing is limited. It was clear he could not hear dialogue that was being deliberately trapped behind the walls of an enclosed sub-set on the stage, and my heart broke again, opening up new interior space in me beyond that intended by the production.

In fact, when the male characters break out from that sub-set, he could hear them, stood on an elevated platform in front of the ‘doll’s house, as I called itearlier, without avoiding a reference to Ibsen’s play of that name (see my blog at this link). It is then that midst of all we see how consciously Daldry wanted his actors to use and make really conscious of the symbolic unreality of the Birling’s home.

In this still, Birling and Gerald relax after the dinner in male only company, and Berling begins to both share his advice and boast of his probable knighthood to come for public service to his son-in law, his wayward ‘queer’ son , in the words of the text, looking out as if from an upstairs window. They make themselves giants against this symbol of bourgeois ownership and family.

It was about five minutes after this point when we left the theatre, just prior to the Inspector Calling. Why? At this point, I found my view blocked again as another long file of school students entered to take the two rows of once empty seats in front of us. Row B filled relatively quickly, but not without drama as young ladies swapped seats to sit next to a bestie or to avoid an enemy. However, Row A, just in front of the balcony edge, was in chaos because those seats were already occupied by the opportunists from the limited-view seats. This took some time to sort, to no one’s satisfaction, and by now, I was not only hearing and seeing less but more conscious that Geoff had been swamped by interruption and blocks to hearing, sight and ability to pay any attention to the play’s progression through its symbolic and fabulous course because of the external disturbances. We slipped through the cracked between Row B and C and up the stairs in high dudgeon with the front-of-house staff, who seemed to think none of this process was unusual to them

But, of course, my temper cooled after escaping. Now, I am no longer angry but sad about it. I sense I have experienced a test case of the breakdown in collaboration between all the agencies involved in a play in order to make it succeed through the stages of its production, projective delivery, and introjection by an audience, especially in a play so obsessed with the notion of maintaining a successful interior integrity in the face of the fragmented and morally contradictory world of fast advancing urban capitalism. That world included including struggles over colonial raw materials, and the world wars that followed, and controlling the cost and the growing independence of the voice of labour in the economy, the state and as individuals.

I felt for Geoff. He’s a tough cookie but has recently had an eye operation, not to say double pneumonia. This had been less suitable for him as an experience than for me. My only recourse was to re-read the play and to try and revive what I might have got from this production.

Lots happens with this set as stills from the production showed me afterwards. The home exterior must revolve to reveal a plush if diminutive Edwardian interior and some of the interior scenes must be played in the cusp of different levels of performing platforms ans sub-stages. Such plays between interior and exterior space must increase the sense that the idea and realisation of fake bourgeois family home values are an illusion of a broken society and the minds who attempt to keep the illusion alive. See below Gerald and Birling who are still in the now front-facing home interior with Inspector Goole in the hard, clear spotlight of his own morally forensic mind.

The Birling home looks as if it has been hollowed out like an inadequate shell to the the family’s preference for its own self-interest and self-esteem, willing to share none of it with the otherwise invisible Eva Smiths of this world. Eva is the victim of this play – an able trade union leader forced by the Birling family into destitution and versions of prostitution. Sheila and Mrs Birling seem jealous even of her superior commonsense and independence of the props of wealth.

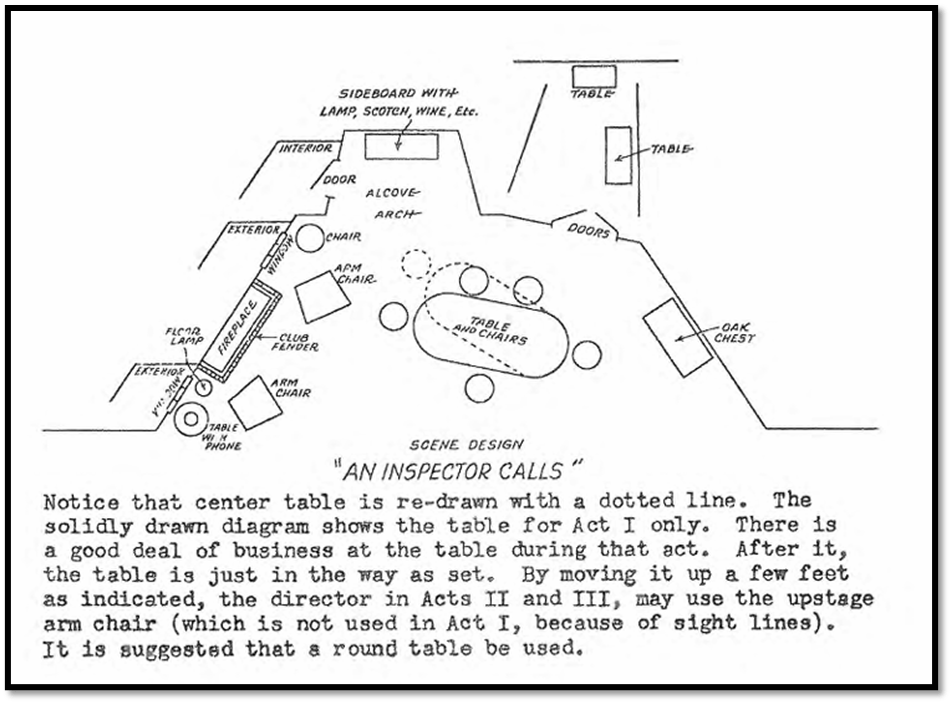

Now, all of this would have been a considerable and beautiful addition to the significance of Priestley’s play. Priestley himself never felt the play need to be literally realistic. Although I think he wanted his audience to sense the claustrophobic self-imprisonment of his characters to be merely because his set never changed (except in turning marginally in a circle) in its first production to ensure the playing areas did not have audience sight-lines blocked by props no longer necessary after Act 1 like the dining table. Here, by the way, is the graphic design of the set provided, and agreed by Priestley, for the (1972, original was 1945) text of An Inspector Calls published by the New York, Dramatists Play Service Inc.

From the text of J.B. Priestley (1972, original was 1945) ‘An In Inspector Calls’ New York, Dramatists Play Service Inc. Available to read at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1-OqusKkEgxuteaSPfX6MZ7-Z2uJVMRyO/view

The design could not differ more from Daldry’s reconfiguration, which made realised scenario divisions between the world outside and inside bourgeois homes that Pristley felt he only needed to hint at in well- voiced prose in which characters, played by actors he trusted) sometimes drop their tasks and covers. His own stage directions evoke symbolic apprehension of the theatrical scene with simple light effects. Here is his first stage direction:

The dining room is of a fairly large suburban house, belonging to a prosperous manufacturer. It has a good solid furniture of the period. The general effect is a substantial and heavily comfortable but not cosy and homelike. (if a realistic set is used, then it should be swung back, as it was in the production at the new theatre. By doing this, you can have the dining-table centre downstage during act one, when it is needed there, and then swinging back, can reveal the fireplace for act two, and then for act three can show a small table with a telephone on it, downstage of the fireplace; and by this time the dining-table and it chairs have moved well upstage. Producers who wish to avoid this tricky business, which involves two re-settings of the scene and some very accurate adjustments of the extra flats necessary would be well advised to dispense with an ordinary realistic set if only because the dining-table becomes a nuisance. The lighting should be pink and intimate until the INSPECTOR arrives and then it should be brighter and harder.)

In the family’s self-absorbed self-vision, the audience shares the light of seeing it as’pink and intimate’. Yet we probably would only notice thus rose-tint when the ‘INSPECTOR arrives’. Inspection sheds ‘brighter and harder’ light on scene and cast, the light of the Inspector analytic method (an avoidance of ‘muddle’ he calls it as Forster and Murdoch would as moral philosophers), isolating each family member for their own internal inspection. The point is Priestley’s like the intellectual nature of drama just as Shaw did, and Iris Murdoch, with whom he collaborated in more than one of her plays and adaptations.

Daldry preferred a more ambitious step away from realism, capturing thd hard life of the have-nots, whom the play’s characters like to overlook rather than care about or do anything other to or for than use [or abuse], seeing them as dispensable workers, service staff or sex toys. Yet the BBC production of this play showed me that attention to text can supply symbolism without massively ambitious set, lighting, and dumb-show manipulations of the text. In the end, text that can not be well-heard because of the symbolic sophistication required of a set, needing to imprison and stifle the voices of the celebrating Birlings for instances, takes away from the collaborative in the theatre, especially that collaborative trust in audience understanding, than it adds. Instead we hear the director’s voice top-down, not offering us a ladder to join him in comprehension.

As a result I think the Daldry tendency might be to stop audiences being grown into good listeners and being trapped instead into visual and possibly unconscious responses. Priestley was part of a theatre that depended onb faith in working-class intellect to see through middle-class masking of its own responsibilities in seeking to lead the public. As Goole says: ‘

Inspector: (massively) Public men, Mr Birling, have responsibilities as well as privileges.

To teach the middle-class to take responsibility he was not afraid of reminding them that an alternative was destruction of their class either from:

- competitive forces of the same ilk in other nations, deaf to the benefits of supposed free trade especially the Third Reich in Germany but not only for the play was first acted in 1945 with Germany defeated again, and eager to get most benefit from international resources not yet being used by the countries from which they were appropriated.

- internal revolution

The mosst poignant statement of this is from Inspector Goole in Act 3. There he says:

Inspector: But just remember this. One Eva Smith has gone – but there are millions and millions and

millions of Eva Smiths and John Smiths still left with us, with their lives, their hopes and fears, their suffering and

chance of happiness, all intertwined with our lives, and what we think and say and do. We don’t live alone. We are

members of one body. We are responsible for each other. And I tell you that the time will soon come when, if men

will not learn that lesson, then they well be taught it in fire and bloody and anguish. Good night.

This plea for mutual responsibility across class, and perhaps other personal differences threatens revolution and war. Daldry – though I don’t know since I had to leave the theatre – had to realise this in visual imagery -with a blacked out Birling house, destructive smoke covering the city of Brumley and a phalanx of soldiers and workers standing behind our Everyman. Had I seen this, I would have loved it, but somehow the contractual knot of meaningful theatre was broken that evening.

For my own role and responsibility in this I am sorry. I agree that schoolchildren have to learn how to attend to theatrical as to any other communicative interaction, and that theatres cannot only serve one kind of theatrical taste in the production or even consumption of the meanings it offers. I look longingly at the theatrical stills of scenes I missed. But somehow that experience has taught me something. This blog was an attempt to learn what is I really learnt. I still don’t know, but writing this has been cathartic.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx