There is a chance that today’s blog will mirror yesterday’s. That is because what I find amongst the reviews of this play is an even more extreme version of the attack on Remi Malek as an Oscar-winner but made this time on Oscar-winner Brie Larson. The attack is the more virulent in that this performance clearly makes alliance of the very stylised and ancient in production values with the dressings of punk and cabaret. The Telegraph critic, Dominic Cavendish, goes as far as to ovrr-voice my own thoughts about the envy in theatre critics of fame in the movies.

There should be a support group for critically battered American stars who’ve made London debuts in duds. [1]

However, the assumption that this production, or even the play that is as famed for its resistability amongst entertainment seekers as it is for its attraction to female actors is a dud needs to be challenged even before I see it. The play attracts female actors of merit and ambition because they so often are looking for a meaningful role that queries the idea of the female performative and its acculturated relationship to passivity in action and dynamism in inner speech and sound that must find an outward manifestation. The text of the 2001 Anne Carson transltion of this play for the production actually reproduces Carson’s brilliant essay as an Afterword. It is called, Screaming in Translation.

Arifa Akbar in The Guardian gets this and why th mere voiced repetitions of negatives to the world’s proposals to her matter to women. She says:

Sound is key to this version of the ancient Greek revenge drama by Sophokles (the production restores the “k” for both the protagonist and writer). Translated by Canadian poet Anne Carson, with crystalline verse, it is filled with ritual stomps, bangs and funereal keening. Sound is Elektra’s weapon too, assaulting the ears. Told she is the weaker sex, her voice is mobilised in protest: “No” is an elongated, rising note she returns to in her dissonant assertion of power. [2]

I started this blog sitting in the waiting room at Durham, awaiting my 8.42 train to London partly thinking of my day. On arrival at King’s Cross, I will walk to get the number 68 bus from Euston concourse for Ancient Thebes via the Old Vic. After the performance, I go to my overnight pied de terre at Covent Garden to await the trip to Mycenae at the Duke of York’s Theatre at 7. 30, to meet up with the long soliloquising of Brie Larson as Elektra. Just as Remi Malek is up for a basting as a Hollywood star, so is Larson, though Stockard Channing as Clytemnestra seems to sail free of the critics envy, perhaps one of the dubious benefits of experience and age.

But at the moment sitting on the train, tapping this into my phone, I am thinking of the day ahead rather than the fate of North American Oscar-winners. Nevertheless, train journeys can stimulate thought, so I keep returning to my theme. I read the reviews with the same mixture of incredulity at the supposed skills, knowledge, and values of theatre critics. There is one very great and appreciative review by Arifa Akbar of The Guardian that gives me hope that my enthusiasm in re-seeing the play, it s my third outing to versions thereof. More of that review as we proceed.

However, the run of the mill of these reviews emphasises even more than those on Oedipus that what scares critics most is the combination of. Ancient authority in stylised Greek drama and the pull of movie stardom. The Independent’s Alice Saville , for instance, starts by emphasising modernity. Larson is a ‘punky rebel’ of an Elektra, rebelling, in this instance against family. Saville continues with a hint of even more suppressed excitement:

Don’t be fooled by the presence of shaven-headed Captain Marvel star Brie Larson in a Bikini Kill band t-shirt – this dream-like staging of Sophocles’s Elektra is closer to the spirit of ancient drama than anything else you’ll find in the West End’s current spate of Greek plays. In true classical style, the action takes place offstage, chanting floods the air, and a round revolving stage mimics a stone amphitheatre. It’s haunting, punchily feminist and perverse, all at once.

After all this, we expect critical rapture, but what we actually get is the summationm9f the whole production as ‘ near-stagnant stillness’ and the sigh that so much h beauty is ‘ultimately impenetrable ‘. Why so negative and why thee assumption that complexity, and stillness te always negative experiences, as if all messages needed to be completely transparent and nothing other than their surface, especially in dealing explicitly and outwardly with ‘inner’ experience and emotion that’d riveted itself even further inward into disarticulation and ‘screaming’, as Carson (and Sophicles I think) aims to ask us to understand.

Teenage punk Larson attempts to articulate t o her mother about the past that she does not want to reproduce

How much of this is a theatrical critical tradition based on things being clear and free of anything that queers normality able to take on board. My feeling is that the reviews on the whole suggest it is very little indeed. Andrzej Lukowski, of Time Out gives it very little time as tjeatre but in the rndblames the failure of the show, in his eyes, on pesky academics-cum-poets, whom he identifies as’syarchy’ without showing sny evidence of knowing her incredible poetry.

US director Daniel Fish’s take on Elektra… is a curious mixture of chaotic randomness and underlying respect for the 2,500-year-old source material.

…. But I’m not sure the average audience member is going to fully appreciate that, and he does very little to help the viewer digest this odd play”

I think the biggest problem for me was ultimately the use of Anne Carson’s poetic but starchy 2001 verse adaptation – there is some mordant wit in there but I’m not convinced the formality of the verse helped the drama even slightly.

Hetecafain critics feel productionnof drsna is to hel an audience to comprend – digest or absorb – rather than to aim for other les cerebral effect. Perhaps that reaction is a male one of the most old-fashioned and misogynistic character, which equates feminity with something ever so neurotic, and, when it isn’t, associates it with serving that used to be used by women ro.launder men’s shirts. Akbar al9ne among critics tries to work out a relationship between impassioned words, subjective interiority, and the recalibration of the fine by the act of saying NO often enough. This passage is critically extraordinary:.

Elektra speaks into a handheld mic and her lines turn into sudden song, harsh or tender (Larson was briefly a singer herself and once released an album). Notes slide up the scale then career back down into spoken word. Sometimes she uses a voice distortion machine, like a death metal singer, to mimic her mother or express loathing to her (“howling bitch”). The anger is never shrill or flatly pitched – her delivery captures not only anger but also grief, resembling Hamlet when at her most melancholy. It is a magnetic performance, fearless for a West End debut.

Weirdly though, the antagonistic tone towards the project is far from confined to male voices alone. What gets to Sarah Hemming of The Financial Times, as it did in her review of Oedipus, is any attempt to portray complex and less than fully articulated emotion. The enemy here is the fear , I think, of any public admission of the reality of the link of oppression to mental illness or disturbance that is fat too easily equated with verbal openness about emotion as in a poetry ‘slam’:

The vision is raw and austere, with Elektra stalking the stage, mic in hand, punching out her words, sometimes with bitter wit, like a sardonic, alienated punk performer at a gig or poetry slam.”

It’s a study in trauma, rage, alienation, but a bit like its central character, it gets trapped in its own world.

I worry here that critics sometimes slip into the expression of acculturated personal fears off what mental distirbance is as a phenomenon. Why should drama not explore alienation, subjectivity trapped into its ‘own world’. Indeed, the greatest dramas do precisely that. Elektra is such a drama, even if it requires a high level of integrated response to it, and that in this one that starts with emotion intuitive from irrational sounds sometimes.

I am typing in the bus now:

However, let’s face it, critics are a group with as many emotionally blocked persons as other groups. It is just that they are empowered to arti plate their blocks as legitimate critical reactions. Take Sarah Crompton in What’s On Stage:

Fish keeps the relationships between the characters abstract and distanced. Larson’s Elektra can shout louder than anyone, because she is literally the one with the microphone. But her speech is – presumably deliberately – flat.”

…. it’s a show in which you see what they were going for rather than really feel it

Do we have to just suck this up and perhaps let it put us off experience out of the norm. Now I cannot and am glad of this. And if you read Dominic Maxwell in The Times, you are unlikely to think Crompton as insensitive as he, who calls the whole production “misguided avant-gardery”. He continues:

Mostly Larson is loud, spitting out her lines close-mic. The other suckers just have to say their lines into the air, fingers crossed they’ll be heard, marginal at best. …

You’ll follow the plot, pretty much, without quite knowing why you should care. Worse, in a way, is that Larson is clearly a gifted, authoritative performer. But she is hemmed into a concept that makes her Elektra only a raging bore. You can see what they are aiming for. But does it come off? Nooooooooo!”

Never has the premises of a play’s feminism, in this case, the power of saying NO to a request for collusion, from powerful authority, with the status quo been more hysterically expressed, male stamping Furies aside. The wonderful Akbar seems to be in empathy with the production in ways that might explain The Times‘ sorrow for the rest of the cast other than Larson. Akbar instances the treatment of the Orestes role in tje play:

Elektra’ s brother, Orestes. Photo by Helen Murray

… there is passing humour, ..the sight of Orestes, in disguise, speaking of the doomed chariot race dressed in a Formula One boiler suit. His role seems deliberately abbreviated, as if to underline the fact that this is a play about women, power and patriarchy. [My italics]

And Akbar is also the only critic not to sneer at Larson’s past work in films like Captain Marvel.

“There’s nothing more dangerous to a warrior than emotion,” Jude Law’s Kree commander tells Brie Larson’s Captain Marvel in the film that secured her Hollywood breakthrough. Anger, he says, “only serves the enemy”.

Theze words, after all, get us nearer to the theme of the play, then any other critic instanced. Akbar makes me hungry for the play, although just now, I am feeding in an Italian restaurant across from the Old Vic.

Akbar communicates something about the chorus if women in this play that delights and that even speaks from the show stills.

Akbar lovex the poetry and loved the production, without referring to its anachronism as some weird mistake. She says that its ‘words are also harmonious in the mouths of the all-female, six-strong chorus (are they band members?)’. Poetry is not music and neither is it drama, some critics suggest – but for the Greeks it was, and can be agaim:

Musicality predominates, accentuating the sense of a sung-through ancient Greek chorus, the text set to composer Ted Hearne’s music. Jeremy Herbert’s set design is a plain arrangement of shadows and sound equipment, some of it overhead, with the stage forever in revolve. It has the effect of a gig gone awry.

After all, why not have the boys there as mere eye candy, if Akbar is correct about that.

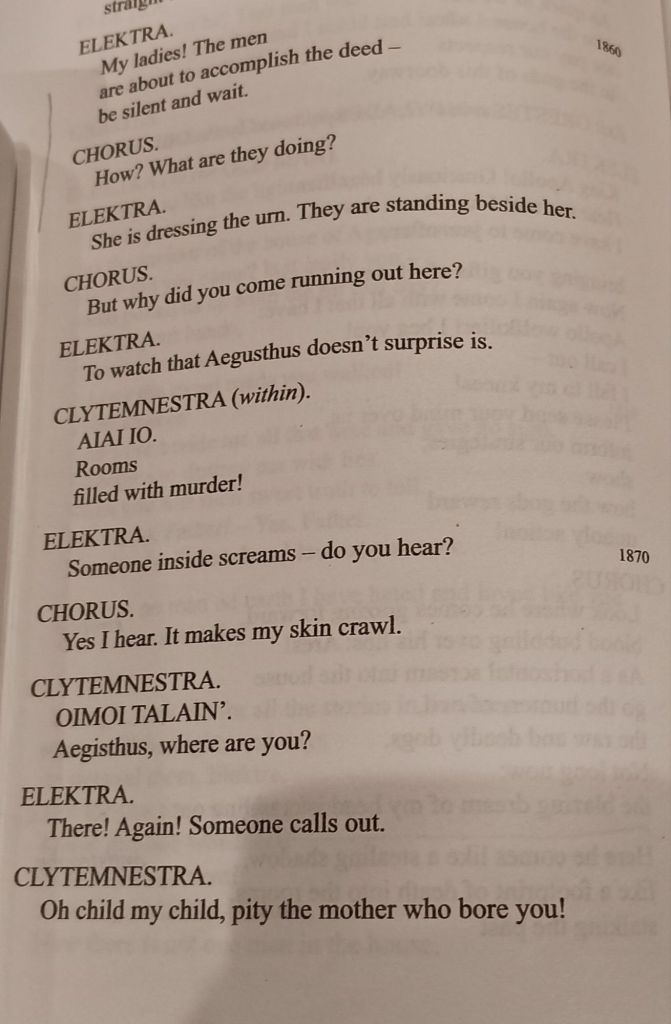

However, in reading the text again, I felt that assumptions about Greek theatrical conventions can be unhelpful. It is true that violent action usually takes place offstage, or in the tiring house of the classic Greek auditorium, but a poetic genius of Sophocles’s ilk is unlikely not to try and turn meaning out of necessary convention. Take the murder of Clytemnestra, out of sight, by her son avenging his father, Agamemnon’s killing by her. The whole scene is sound and poetry. Its meaning is about the limits of internalised violence as an expression of self:

Of this and other moments, Akbar says:

Violence remains off stage but is insinuated with a device in which a modern-day massacre is described through reportage. This works, but there are some more mystifying or achingly cool elements: a blimp dangling over the stage, out of keeping with the rest of the imagery; a smoke machine that exhales swirling plumes as Elektra’s returning brother, Orestes (Patrick Vaill), prepares to kill his mother.

Let’s see if this is spurious, but what I am watching for is some attempt to play out Elektra’s psychological drama in which exteriority and interiority, male and female, outward seeming and internal complexity play against each other. This had, for Sophocles, to be about contemplation of the inadequacy of the sex/gender binary in speaking of the agency of emotion. Now, I can not wait to see the play.

I can, of course. It is now 1.30, and Oedipus begins in an hour across the road at the old Vic. Lunch is finished.

For now, goodbye.

All my love

Steven xxxxx

‐—‐—————————–

NOTE IN WEST END THEATRE: The production also stars Stockard Channing (The West Wing, The Good Wife, Grease) as Clytemnestra, Marième Diouf (Romeo and Juliet, The Globe) as Chrysothemis, Greg Hicks (Grapes of Wrath, National Theatre; Coriolanus, The Old Vic) as Aegisthus, and Patrick Vaill (Stranger Things: The First Shadow, Oklahoma!) as Orestes.

[1] All reviews other than Akbar’ s are cited from: Elektra reviews round-up starring Brie Larson at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London | West End Theatre https://www.westendtheatre.com/274068/news/reviews/elektra-reviews-round-up-starring-brie-larson-at-the-duke-of-yorks-theatre-in-london/

[2] Arifa Akbar (2025) ‘Elektra review – Brie Larson makes a fearless West End debut in punk tragedy’ in The Guardian (Wed 5 Feb 2025 23.30 GMT)