Tomorrow I travel to London. My first destination experience is travelling to ancient Thebes recreated on the stage of the Old Vic Theatre to see Ella Hickson’s free adaptation of Oedipus. Reviewers’ comments have ranged from deliberate disdain to the usual passive-aggressive attempts to take down the reputation of visiting Hollywood stars alongside praise of the production values of this version as realised mainly in choric dance. Hence, I am glad to read the published script of the adaptation first.

This blog moves one from an earlier one available at this link. I have also addressed before the importance to me of preparing myself through reading what I can (text and reviews) before visiting new stage productions (in the linked instance below it is in the case of a Brecht play adapted by Denise Mina that was cancelled by COVID-19 before I saw the real thing (the blog is linked here). The COVID cancellation prompted another reason I was glad to read and think out a new version of a play first (in that case one I had not read and seen in very many versions first). In most cases I do not read ahead to recapture the narrative, even in stories that are so fertile of change as that of the Labdacid dynasty whose curse started in the rape of a host-royal-family’s son by King Laius. After all, though people claim to hate stage adaptation of Sophocles’ Oedipus’ for its lack of truth to Sophocles story, there is little justification for this in ancient theatrical practice. After all, one thing we do know is that Sophocles’ telling of the narrative was one amongst many – even many probably by him. Yet here are some critical comments of that nature that make so many assumptions about what thoughts and feelings the story ought to evoke, some (Sarah Hemmings, for instance) with mor of a home in Freud than Sophocles:

I’m all for interrogating a text, but just taking out the stuff that has kept Oedipus popular for 2,500 years is, is, ironically, the biggest display of hubris in the show.

…

Not wishing to spell it out, but the story comes to a head with the usual revelations, following which there seems to be an aggressive commitment to making the most famous tragedy of all time not actually tragic. Spoilers: Varma’s Jocasta is virtually unbothered when Oedipus’s true parentage comes to light. And Malek’s Oedipus’s final act of self-mutilation comes across as more of a cynical political gesture to save his own skin than an act of despair.[1]

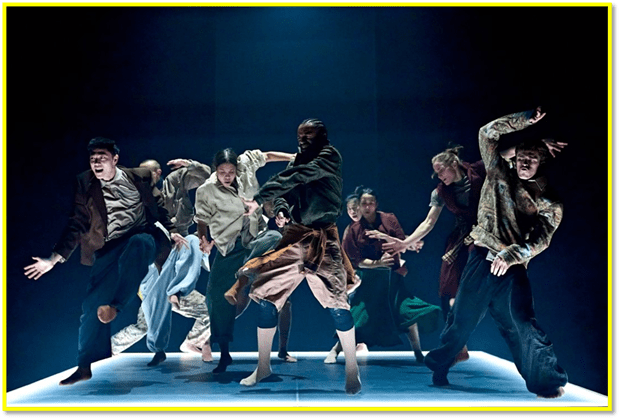

… there’s something here that doesn’t click. The dance segments mean the story is splintered, delivered in clipped, disjointed sections, and we lose the urgency and skin-prickling dread that should accompany Oedipus’s journey.[2]

The opening is dazzling… It’s fabulous, an absolute vindication of this new production of Sophocles’ great tragedy of self-knowledge, co-directed by Matthew Warchus and choreographer Hofesh Shechter who provides not only the dance but also the music. But it can’t sustain the intensity it promises. By the end, there’s not much catharsis and without that, there’s not much tragedy. Yet en route, there are tantalising glimpses of wonder.[3]

Hickson has interesting stuff to say about populism, faith and fanaticism, but Oedipus works when it’s an inexorable plummet towards revelation and tragedy; here, whenever the tension starts to ratchet up, something weird like a sassy Tiresias (the wonderful Cecilia Noble) or a long dance sequence cuts it dead, like we’re flicking through different TV channels.[4]

By the way there is no need to worry about Andrzej Lukowski’s spoilers in the first quotation (from Time Out) – he doesn’t even mention the major plot revision, and may have not understood it. The faux horror evoked in these critics (David Jays in The Guardian is a honourable exception so isn’t there) by Hickson’s changes in the narrative in this version – deliberately made to confuse because toying with two possible endings in the minds of its plotting characters – have no justification in Greek drama. In The Greek theatre revision of the narrative of extremely well known semi-religious myths was de rigueur, and often in order to comment on contemporary politico-religious ideologies.

Euripides, for instance, in his The Phoenician Women, has blind Oedipus, Jocasta, Antigone and others live on in Thebes to experience the attack on the city by Oedipus’ rash son, Polyneices with allied Greek state armies (another story for which the canonical version is Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes). See how these critics all jump for their A-Level knowledge of ‘catharsis’ or ‘hubris’ in Greek tragedy, without understanding that both concepts are generalisations from Aristotle’s Poetics, rather than from the little we know of the contemporary reception of the plays themselves.

In the remnant of my introduction, like Lukowski, I will not hold back from spoilers so STOP READING here if such things matter to you for the spoiler he does not reference but I will is a key one in the experience of the play and cannot be known in terms of an effect on the story’s denouement. Nevertheless, spoilers there must be if we are to understand the wrong headedness and mean spirit of most of the critics of this play – Time Out, The Telegraph and the Daily Mail’s critics (Time Out there in bed with strangely horned and politically motivated bedfellows) being the worst offenders I think.[5]

However, let’s start with a reading of the play she saw by Fiona Mountford of the I newspaper. She says when apparently discussing the quality of Remi Malek’s acting performance that:

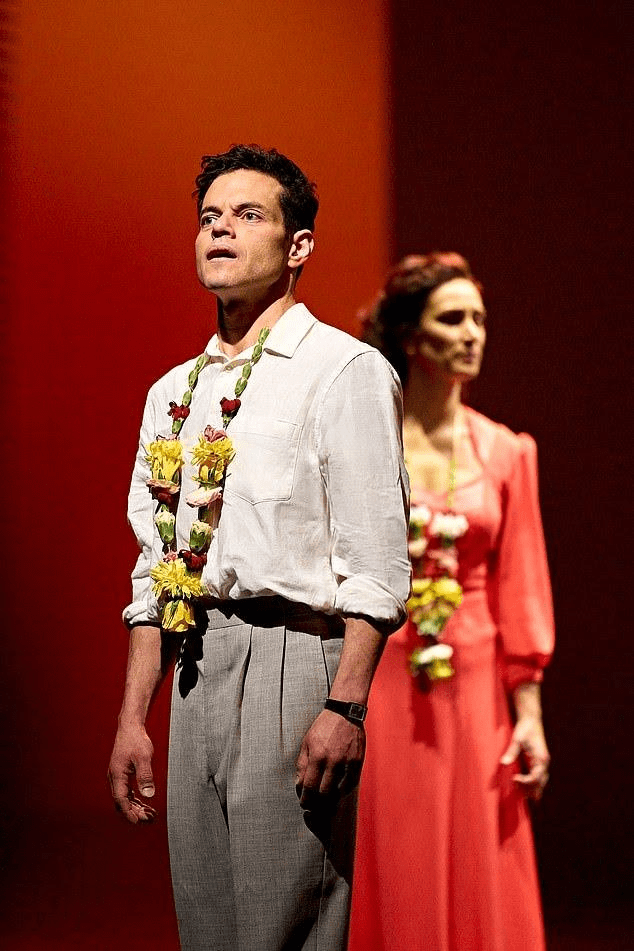

His Oedipus is an emotionally detached man, superficially calm yet full of a coiled stubbornness that borders dangerously on monomania. It is very hard to escape the feeling that Thebes would have been considerably better served with Jocasta as its leader; Matthew Warchus’s production certainly benefits more from Varma’s presence than it does from Malek’s.[6]

This is, in my view at least, terribly confusing as a commentary on the play but not untypical of how newspaper critics address these issues about the interaction of acting, production values and the contents (intended or otherwise) of a play’s text. AS I read the play (what I see at the Old Vic I will report later) very much justifies the view that Hickson wanted us to see Jocasta as the kind of leader any rational populace would choose or electorate vote for, were it not mandatory that rulers were patriarchs first and foremost. To see ‘monomania’ in Maek’s Oedipus character, is NOT, as the Mountford’s tone suggests, some weakness in his acting performance but a sign that be gave what the text demands of him. Mountford is not the only critic to sat that there is a kind of madness in this Oedipal character and neither is she alone in finding in that a stick to beat out the presumption that he can act from yet another Hollywood star. Lukowski says:

Hollywood star Rami Malek plays Oedipus as a detached, drawling figure who may or may not care about the drought, but seems to be so off his gourd it’s hard to tell. I’m inclined to believe this a choice rather than bad acting, though his performance is hardly the strangest thing about this show.

Like Mountford choosing a name- monomania – categorising madness that has not been in use since the nineteenth century (by Tennyson and Browning for instance to describe openly insane speakers of their dramatic monologue poetry), there is even less sophistication about mental illness in Lukowski’s ‘so off his gourd’. Tim Bano in The Evening Standard prefers sticking with folk terminology for the ‘madness’ of Malek’s performance: ‘Rami Malek seems like he’s on a different planet …’.. However, unlike Mountford or Bano Lukowski raises the debating point that Malek may act that role as that of a man askew from internalised norms of sanity intentionally, and having read the text that seems the choice that I think the best actor there could be of the role would very consciously choose. After all, since Freud, the name of Oedipus has named the psychological complex out of which he, at least believed most neuroses and some psychoses originated. Bano thinks however Malk’s apparent insanity is a characteristic of the production in different ways, pointing to its ‘restlessness’ of scene shifts and the ‘disjointed madness of these miscellaneous spectacles’ that are its use of choric dancing interludes performed by the Hofesh Shechter Dance company.

Other critics find the dancing masses, representing the force of populism when it gets hold of a topic like the need for patriarchal authority, as in Trump’s America and, as Farage aims to bring about in the UK frustratingly unacceptable. However, in my reading this is precisely how Hickson works to metamorphose the Sophocles text in order to produce a text on the symbolic nature of the authority of leaders. David Jay’s review in The Guardian is solitary and exemplary in finding the kernel of how we should evaluate Malek’s performance as recording the neurotic shifts of leaders who from fear of a people gone mad, as in Trump’s making of ‘America Great Again’ turns inward to objectify that populist madness in himself, even down to an inability to face family history except through neurotic response to ambiguous ‘divine’ communication.

[Rami Malek] brings outsider vibes to Oedipus – speaking in an elusive American drawl, adopting the mantle of leadership like a haunted robot. Confession later fractures his speech – he becomes shambling, disjointed, bones awkwardly resettling in his body. The truth remakes Oedipus, and then undoes him.

We see here that Malek’s acting performance might exactly fit his remit – his disjointedness (if that is what I see) matching that danced by Hofesh Schacter Company as chorus. That also explains why critics recognise Indira Vharma as the better actor (or Jocasta as the better role) – critics are often unspecific about that distinction. In this text, Jocasta is set up as a rationalist, aware that rational though may have to sit out the irrational times in politics and (watch it – here’s the spoiler!) she escapes Thebes, with an intention to return in better times, although she too begins to crack up neurotically, rather than psychotically like Oedipus. She insists that things needn’t be like this: “it wasn’t a given, none of it was a given, it’s fear, it’s always fear, every time … I said, I told you – fear makes it happen: it drives it – don’t let it, fight – the ….”.[7]

The traditional ending of the play (with report of Jocasta’s suicide by hanging) is restored by the corrupt populist Creon as a lie as expertly told as Elon Musk might tell lies to diminish rational public policy. He tells Oedipus that this was the ending, who says: “Is it true?”.[8] Of course, it’s not true, but the point is that politicians who blind themselves believe anything, even the conventional endings of Sophoclean tragedy and the interpretation as the fate of men who turn from the Gods to believe in the power of human rational thought.

And even the best stills available from the production, show a man looking away from the good sense of his mother and wife, who even feels able to live with that unthinkable conundrum in Western culture, and when unable to look in a different looks into the dark abyss within.

In fact not only David Jays gets the same meaning as I do, but as yet I do so only from reading the text, but also Lucy Popescu, that champion of the literature of migration. Of the production altogether Jays get the relation of the play top the Greek tradition right because he does not rely on Aristotle as British education on this theme has long done:

Dance in Greek tragedy – why not? The ancient Athenians did it, their choruses a weave of sound and movement, though no one really knows what shapes they threw back in the fifth century. They probably didn’t give the hands-in-the-air delirium of Hofesh Shechter’s spectacular dancers in this new version of Oedipus – but dance becomes the irresistible core of the tragedy.[9]

Popescu takes a similar approach:

IT’S an inspired choice to use the as a Greek chorus … Their writhing, frenetic movement, set to choreographer Shechter’s exhilarating music, emphasises the ritualistic elements of Sophocles’ tragedy while, in turn, evoking an unruly mob and our own helplessness in the face of a climate crisis.[10]

And she is right. Politically it is the failure of political leadership to be other than blind to climate crisis, water shortage and ecological extinction and to rely on the adaption of political myths that the play enacts I think, even in the script’s description of the set, which I cannot wait to see in the flesh:

Sun: there is nothing. Dirt and arid desert; hard, cracked ground. An unforgiving sun sits low in the sky giving perpetual scorching heat. Even at night, there is no relief.[11]

But Popescu still seems to feel that ‘production values’ of high order mean that traditional acting performance values fall short and in relying ‘on spectacle, rather than emotional depth’ that ‘the lead actors are eclipsed by the production values (and, dare I say it, the dance troupe)’. I think this is to deny that the actor’s craft requires more in its evaluation than the Stanislavskian and British tradition to evaluate it – what of Brecht, Artaud, or even Fritz Lang. Still its better than Lukowski saying that the whole thing ‘ is just completely fucking nuts’:

Climate change is never mentioned, but given Hickson’s main thrust seems to be interrogating the religious assumptions that underpin the story, it feels like there’s an underlying question about whether gods or man have turned the taps off. Whatever the case, Tom Visser’s lighting is stunning – there is a real Dune thing going on, a ravening orangey-redness that threatens to consume all.

It’s a compelling backdrop but the foreground stuff is… baffling.[12]

It remains true that just because you don’t understand the thing you see and hear playing out in front of you that ‘its ‘fucking nuts’, although psychiatry has sometimes offered a model of just that. It is even more the case that viewers like Sarah Hemming in The Financial Times who fail to see ‘emotional connection’ or ‘tragic pathos’ may be looking for it in too obviously a performative style.[13] Moreover do newspaper critics really know what in a play gives it ‘poetic heft’ which is what The Times says Hickson’s script lacks. I just disagree here. Even the stage directions have something of that ‘heft’.

Moreove,r though the Daily Mail like others calls the performance ‘curiously stilted’ perhaps because it come from, in their terms, ‘Oscar winner Remi Malek’, even they admit that such ways of talking may have meaning in a recognisable world of power differentials: ‘His American-accented king is stiff rather than regal, his rigid facial expressions evoking all those socialite millionaires who’ve gone in for a few too many injections of Botox’. The script does not emphasise Oedipus as ‘Tyrannous’ but as someone trying to wear his political authority in a new way as his dialogues with Creon show:

CREON: A man of faith, is a man of strength. My faction follows me without question.

OEDIPUS (smiles) Yes, Creon – but not everyone is looking to be followed without question. Your robe is slightly askew.

OEDIPUS rearranges his robe for him.[14]

There is much in that exchange to watch out for, before you decide how good a stage actor an ‘Oscar-winner’ can be. And Hickson makes it clear that Oedipus believes himself a kind of democrat: ‘You elected me as your leader’.[15] I will be watching tomorrow, for there is something rotten in the state of British newspaper criticism, as indeed of Britain’s press generally.

Can’t wait to catch my train now.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Andrzej Lukowski (2025) ‘Rami Malek and Indira Varma star in a bizarre dance-theatre remake of the Ancient Greek classic that tinkers the tragedy out of the drama’ Old Vic, Waterloo Until 29 Mar 2025 in Time Out (Wednesday 5 February 2025)

[2][2] Sarah Hemmings in The Financial Times, as found in Reviews Round-up of Oedipus at The Old Vic starring Rami Malek & Indira Varma | West End Theatre: https://www.westendtheatre.com/273849/news/reviews/reviews-round-up-of-oedipus-at-the-old-vic-starring-rami-malek-indira-varma/

[3] Sarah Crompton, What’s On Stage in ibid.

[4] Tim Bano Evening Standard in ibid.

[5] All referenced: ibid.

[6] Fiona Mountford, The i Paper in ibid.

[7] Sophocles & Ella Hickson (2025: 43) Oedipus: in a version London, Nick Hern Books

[8] Ibid: 45.

[9] David Jays in West End Theatre op.cit.

[10] Lucy Popescu (2025) ‘Breathtaking production evokes our own helplessness in the face of a climate crisis’ in Camden New Journal (online) [Thursday, 13th February] available at https://www.camdennewjournal.co.uk/article/review-oedipus-at-old-vic

[11] Sophocles & Hickson op.cit: 11.

[12] Lukowski in West End Theatre op.cit.

[13] Sarah Hemming The Financial Times in ibid.

[14] Sophocles & Hickson op.cit: 12.

[15] Ibid: 16