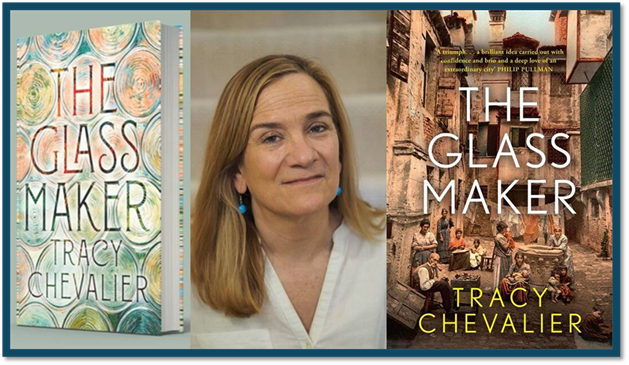

‘People who make things also have an ambiguous relationship with time. … Its surprising hard to gauge the rate at which time passes – whether it moves faster for others than it does for you’.[1]Appreciating the motion of passing time in Tracy Chevalier (2024) The Glassmaker London, The Borough Press.

Is it a spoiler to say that the story of Orsola Rosso, the protagonist of The Glass Maker, comes to our attention as a girl as he transits the canals of Venice in or near 1486 and never dies through the duration of the novel. The last full story in her life occurs, wherein we see her confront the Covid epidemic and lockdowns in 2019 – with a last cameo appearance in which she contemplates the passage of time some unspecified time that is called ‘the present’ she is said to be ‘in her late sixties’. Whether that last moment of our acquaintance with her means the present as it was at the time of the novel’s publication (2024) or the present time in which the reader reads it (February 2025 for me) or some other time for past and future readers is necessarily unclear. It has to be unclear in order to accommodate readers yet unidentified as such. Alan Massie, in The Scotsman, is enviously specific about the measurement of time gaps in the novel (more than I dare to be so), and says: ‘So the heroine, Orsola, glass maker’s daughter and herself to become a maker of beautiful glass beads, is nine in when we first meet her, but still only 65 more than 500 years later’.

Massie obviously had difficulties with the time-phasing of the plot and I have to admit to the same, for a while. Yet I agree to entirely with his conclusions about this too.

This may seem tiresomely tricky, affected even. That indeed was my first thought. Yet what matters in fiction is what works, and here it all works very well indeed.

….

… . I began it with some misgivings, not least because the structure threatened to be self-indulgent and whimsical. That fear was unfounded, however. Once you accept the premise that the Rossa family and those they know and deal with live in a different time from the world beyond Venice (though they are inevitably made aware of the world beyond the lagoons) everything holds together. It is a very clever novel, but wholly free from the self-satisfaction evident in so many clever novels, It’s fantastic, but yet rooted in reality – and there is sadness, of course, because it is a family story and true to life, and because Venice is now so melancholy a place.[2]

For Massie, the handling of time seems to reflect some sad feeling about Venice itself as a backward-looking place in its architecture and the lives of its people, and this indeed is justified by things in the novel’s story and its description. Throughout Chevalier calls the motion of time in her novel, for her main character – at least those who stay on the island of Murano or the city of Venice – ‘time alla Veneziana’. But time is about more than feelings or affect (to use the psychiatric term) – though they are central too – it is about the ontology of things and the epistemology of how these things are known and described.

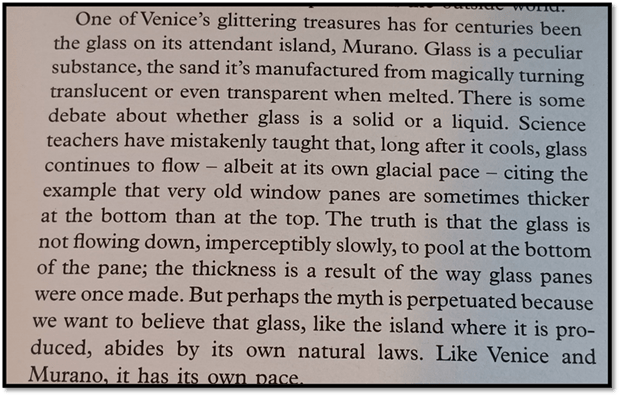

Chevalier is not an intellectually showy writer and avoids the academicism one finds sometimes in A.S. Byatt’s wondrous fiction, but she hints at these deeper intellectual strands that are located in the contemporary history of the science through which he herself has lived. In her ‘A Brief Explanation of Time: Alla Veneziana’ (that prefaces the novel – not much longer than a full page) she appears to muse on myths about the ontology of glass, which is, after all, a topic that takes up much of the novel’s time and space, and, while she corrects them, shows how attractive they are for her as a writer.

My photograph of Chevalier op.cit: from page vii

The language is all very much in the register of everyday conversation: ‘Glass is a peculiar substance’, she says without seeming to want to lean into the philosophy of science (or metaphysics as it is called). The idea of a debate is mooted and the level of it fixed at that of ‘science teachers’, but the summary of the debate and the example taken to illustrate it – the apparent pooling of glass at the base of stained glass – is the same mentioned in popular accounts of the scientific proofs that solved the issue relatively recently in time. The paper cited in the popular science ezine Gizmodo appeared on the 30th April 2013 only (nine years ago but a very short time in this novel’s fictional span, and possibly in Chevalier’s time for writing it, though to be honest Chevalier has published 4 novels since then.[3]

Gizmodo’s correspondent George Dvorsky summarised the paper thus: ‘By studying a glob of 20 million-year-old amber, scientists have proven once and for all that glass does not flow’. But then follows a passage that mirrors Chevalier’s, although I claim no influence of it on her – it is obviously how the issue was debated in 2013 and which Chevalier could have found anywhere:

Some people claim that stained glass windows in old churches are thicker at the bottom than at the top because glass flows slowly like a liquid. We’ve known this isn’t true for quite some time now; these windows are thicker at the bottom owing to the production process. Back during medieval times, a lump of molten glass was rolled, expanded, and flattened before being spun into a disc and cut into panes. These sheets were thicker around the edges and installed such that the heavier side was at the bottom.

But the myth that glass flows has persisted over time.[4]

There is little point in further summary of the paper – although here is Dvorsky’s linked reference to it – “Using 20-million-year-old amber to test the super-Arrhenius behaviour of glass-forming systems” – for its scientific rationale is unnecessary for our purposes as readers. Chevalier’s preface merely states that we now KNOW that glass is a solid not a fluid, in the present appropriate usage of these terms, but that the ‘myth’ persists – and will be used as an analogy by her for describing the process of time’s passage in her novel. And that idea is useful for our purposes, for it shows that Chevalier did not want to be merely fanciful in asserting, in Alan Massie’s words again (for he uses the Scottish word for the English one ‘skilful’, skeely), that:

Time in Venice moves differently from time elsewhere, very differently in Tracy Chevalier’s engaging new novel. In her first sentence, …, she writes about a stone skimming across water, with moments in the air before it touches water again, and then again, if you are a skeely skimmer, as indeed she shows herself to be.[5]

To point out the vitality of myth used in Chevalier’s writing we only need to notice her use of the word flow – the active verb for describing what a fluid – but not a solid – does in the gap of time and at different paces dependent on the viscosity of the fluid. Novelists like to use words in ways that exploit homonymic, and sometimes homophonic, qualities. In her prefatory piece she compares glass makers to other artistic and craft creators because they all are capable of entering ‘an absorbed state that psychologists call flow. In which hours pass without noticing’.[6] One humanistic Hungarian-Italian-American psychologist in particular is associated with the word ‘flow’: Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. For him flow is a phenomenological state of being but it derives from the metaphors used by his qualitative research participants.

We have called this state the flow experience, because this is the term many of the people we interviewed had used in their descriptions of how it felt to be in top form: “It was like floating,” “I was carried on by the flow.” ( Csikszentmihalyi, ‘Flow’ 1990).[7]

In fact flow as a phenomenon does not in this novel only cover our experiences of being ‘in top form’: for how likely would this be at any time in the history of working people. The issue in this novel is the difficulty of falling into flow experience and the dangers of misjudging such moments. Take the death of Orsola’s father, Lorenzo Rosso, which happens very early in the novel so no terrible spoiler here, Mishandling the heated solid glass shape (heated so that it can be manipulated into shape and function, ‘possibly the arm of a pitcher’, by Lorenzo, the maestro of the workshop) a feckless apprentice drops it. A shard of the broken glass- soft at first but soon hardening – pierces Lorenzo’s neck and he dies in a sheet of his own pooled red blood. This is one of the many contingent events in the novel that interrupt the flow of time and pool or dam it but which are in fact part of it. Chevalier plays here with much symbolism. The issue of the Rosso bloodline is vital to the flow of this novel – in determining, for instance, who it includes and excludes from that flow of the family’s fortunes – but the name Rosso is also the red colouration of the bloodline, a point continually recalled in the novel – in the colouring of the glass beads later made by Orsola and the goblets made by her brother, who becomes maestro after Lorenzo. But the flow of blood is an urgent symbol on Lorenzo’s death.

When the death happens Orsola is bringing into the workshop reserved only for men in the family, a stew of eels. She drops the stew and its contents – once at home only in fluids – into the flow of blood that has gushed from Lorenzo. Orsola’s mother calls for sheets – they are white of course but brough in by her daughter-in-law Maddalena. The whole scene is one that shows how the flow of narrative is slowed up and, for a time, stopped in the still and thickening mess of the present time. The word ‘flow’ is used once but implicitly it is there throughout – being STOPPED!

How do we respond to mess? Especially how do women respond to contingent mess caused by men, whom themselves so disregard the work of women that it is carelessly ‘ruined in a flash’ as Orsola’s work is here, and that of other women washing clothes and sheets, caring for the sick and making meals (let alone setting up a bead workshop and then factory)_ Men prize their bloodline but so often let their bloodline pool into a mess of blood, that is a kind of obscenity. But eels cannot swim in blood alive, though they may look as if doing so dead. Laura (Orsola’s mother) is ‘stemming the flow’, merely because it is all she can do. At some time the flow of life, whether of an individual person, a family or a social group stops (or appears to do so – I will consider this in terms of anormative and race terms later).

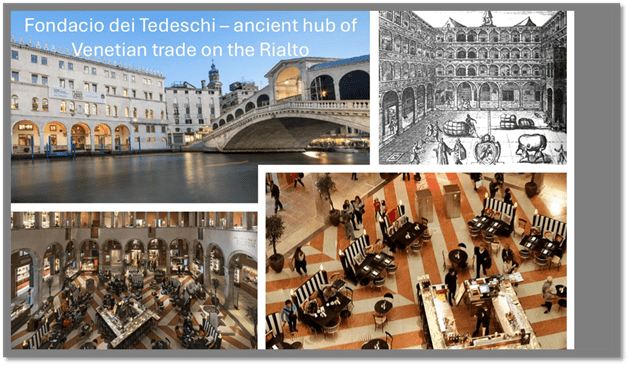

Sometimes the sense of flow that predominates is one that links the sensation of purposeful motion (though the purpose remains occulted or unclear) in an individual to that of whole crowds and masses, A favourite example of mine I re-found by accident – it is where Orsola feels the tug of change where the familiar yields to the strange and queer movement of global history – of migration, trade, the international. It is the moment where Orsola takes the first fruits of her productive work to be examined by the German merchant Klingenberg. Having foiled petty theft of her goods by a ‘boy who rarely reached her chin’, she clutches her bags to her and begins ‘to wade through this city full of movement, of people, goods and water’.. The prose conducts itself by way of metaphors of watery flow and resistance both that it also quietly performs in its prose rhythms as the slow wade of this sentence through resistant water begins to flow more strongly and agentively. That resistance followed by a strong sense of flow also mimes the arduous of the learning to work and then working on her beads samples and their transit then to the Rialto – the world trading hub of the Venetian Republic[8]. It is as if we were being carried on from a world dominated by the power of state and church to the age here capitalism and its notorious contradictions begins to be the source of shifting power bases.

:She made her way along a passage roughly in the direction of the Rialto, chiding herself for being so careless as to almost lose more than a month’s work. It made her reluctant to ask anyone if she was going in the right wat. But from the steady stream of people all heading along the same calle, turning confidently here and there, it soon became apparent that she was. Orsola floated along in the crowd like a stick heading inexorably downstream, moving from the political and religious centre of the city to the commercial quarter.

The old world is being passed through the body like excrement in the stench of the canals she crossed, full of rotten vegetables and the contents of chamber pots’. She floats into the ‘sounds’ of a new mix of multicultural trade : ‘plenty of Venetian, but also a babel of languages she didn’t know. Turkish/ Greek/ Arabic? German? English? French?’. It is as brave a new world as that encountered by Miranda in The Tempest:

This Venice was thrilling, and Orsola wanted to be where she was, in the centre of it all; but part of her wished she were at home, safe from all this strangeness.

This is the experience of existence in time featuring the dynamic between the pull to the past that is Heimlich against the Uncanny / Unheimlich of the future. Yet to the latter we must flow though it will take Orsola five centuries to do so. And in Venetian terms this means this particular transport of her first sale of commodities in the watery ‘stream of people’ that ‘spat her out in front of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, the home of Venetian trade and the hub of international capitalist relations as an idea,

This flow is not all straight ion. Leonardo Da Vinci was fascinated by the forces which caused eddies and whirlpooling in water. See this highly accessible account by Anita Louise Art blog thereof, starting with one of his notable gnomic statements:

“Water is the driving force of all nature.”

For Leonardo, water was not merely a passive element; it was a dynamic and powerful entity that shaped landscapes, nourished life, and, when unchecked, could cause destruction. His understanding of water as a creative and destructive force deeply informed his work.

Leonardo’s Studies of Water in Motion

Leonardo’s fascination with water is evident in his numerous studies of water in motion, often categorized under the broader term “hydrodynamics.” His sketches depict water swirling in eddies, cascading in waterfalls, and flowing in intricate currents.[9]

Whether as influence or not, Chevalier doggedly follows through her narratives fully conscious of the metaphor of water courses – in canals, rivers, seas and oceans, including the eddies where events appear to turn on each other in a dynamic swirl – like the pictures of the plague in Venice in the 1570s and the stopping of the flow of people between engagements with each to the Covid epidemic lockdowns in 2019,[10] But nowhere does Chevalier suggest that history merely returns to its same self here. Eddies occur – sometimes ones involving huge cycles of time but the onward flow is inevitable for good or evil – an issue about which the novel remains undecided. They rhyme with each as events because both are about times of containment that extend its seeming duration: ‘One day was much like the day before and the day after. Cook, eat, clean, make beads, sweat, wait for Antonio, ..’.[11]

And all this is complexly nuanced with the history of glass and glassmaking, which if it moves slower than in other crafts, does indeed move – considerably over 500 years, influenced by markets, techniques of making, fashions and tastes, Hence the import of the myth of the flow of glass as if it were a liquid of the very densest sort. When Orsola’s rough-house brother, Marco (becoming a maestro in glassmaking before he was ready – before his time as it were – on the premature death of his father) begins to cause the Rosso glass business to fail – being neither traditional nor modern enough either way to meet demands – he drinks alcohol inordinately. Looking for him, Orsola hears tell from a Venetian taverna owner of Marco the night before talking ‘a lot of nonsense about the “flow” of glass. Can’t say he made any sense’.[12] Once left by her lover Antonio, a queerly transexual being, but still receiving over long periods, that measure her time of her abandonment, glass moulded dolphins that cause her to wonder if Antonio, though he has abandoned the slow moving time of Murano, the island of glassmaking, and the slightly faster but still slow-moving flow of Venetian time. The dolphins collected together indeed ‘click’ like a clock – some measure of time – when unhooked and she lets them do so:

The dolphins were precious to her, for they were concrete indicators that Antonio was still connected to Murano and to her. Perhaps the slow flow of glass remained in his blood, even on terra ferma. She was willing to believe this.

Terra ferma – SOLID EARTH – has little of the fictive malleability of time (as glass has as a fictive mythical but not real liquid) and the novel will show her, neither has Antonio (bit that may be a spoiler. The theme her is one of how time is, if at all, measured in its motion. The skims of the stone across a Venetian lagoon skips over vast gaps to hit the flow of time only momently. So with that conventional measure of time we called the calendar, yearly or as a sequence of theoretically unlimited years, but still an fiction imposed hard down from the top on people below by Late Roman and Byzantine Emperors, Popes and, in the nineteenth century the rigidity of need in railway timetables. For Orsola the skips occur in the distribution and fictive making of Chevalier’s fluid narrative structure. For example skips and gaps like these: 1494 – 1574, 1533 – 1765, 1766 – 1797, and thence skips to 1915 and 2019 before the last one that is undated.[13] All of this narrative machinery tells us about te folly of quantitative measurement in relation to questions of human development and notions of a flow representing the idea of human progress – there is onward movement but progress is more difficult to measure, as in the learning of beadmaking for it is a matter of time and variations of human difference.

We think for instance that ‘events’ and their qualities may measure time, and Chevalier gives a list of world, and literary events at these gaps, including on mention Virginia Woolf on the leap to 1915 that: “The novel has come of age”.[14] Yet if it comes of age it does so in the light of people like Henry James describing the fictive fruitfulness of a Dickens say (or the three volume novels such as those by Thackeray he was really talking about) as making novels that are ‘large, loose, baggy monsters’. In the preface to the New York edition of The Tragic Muse he says: “what do such large, loose, baggy monsters, with their queer elements of the accidental and the arbitrary, artistically mean?” [15]

‘Queer elements of the accidental and the arbitrary’ quoth James. There is a severe lesson intended for the matured ‘modernist’ novel here. Novels are matters of craft and design is the underlying message and no competent designer includes matter from that is merely contingent in time ‘the accidental and the arbitrary’. It is almost Vasari resurrected to continue the disegno versus colore debate in art. It resembles the debates about whether design or accidental and thematic colour matter in the making of lampwork beads, and the ‘dumbing down’ of glass craft in seed bead manufactories and picture-making. It most resembles Chevalier thinking about how an artist in the novel, post Virginia Woolf design, applies both manipulation of event and the accidental recording of the contingent messes and muddles into which time for a duration circulates and sometimes coagulates, like the ‘hard time’ imposed on Venice by Austria in the nineteenth century.

The problem with novels for novelists and their readers is in their ability to find time for their making and consumption that meets the needs of the present and the standards of longer lasting traditions. When Orsola sighs: “Glass is so hard to control” to Klingenberg, we hear Chevalier sigh too about novel-making. Both receive new heart in the voice of Maria Barovier, that prototypical female artist who gets on with despite her knowledge of the rigid rules of patriarchal dominance. For Chevalier too the novel is an ‘unpredictable mistress: it has its own laws’. Maria continues:

You have to practise more before you show your beads to Signor Klingenberg. He needs to have no reason to turn you down.[16]

Chevalier knows why she values Orsola as a protagonist at the end of the novel – it may take 500 years of responding to contingencies of the market and accidents of time and in series and cycles but she she is recognized by her maker for being a maker herself. Chevalier like Orsola knows she has crafted beauty (her dolphins) and that she will be part of history, though still at the end of the novel, she is ‘not yet ready to let go of her history’. Nevertheless she imagines posterity though the reactions of women who gaze at her pieces and their design modelling and say to themselves: ‘She is a maker’.[17]

In my opinion Chevalier tests her grasp of the contradictions of human time by seeing how the passage of time metamorphoses issues of the representation of humans. It leads to poignancies that are moving, beautiful but puzzling for they query the categories that humans seem to invest through historical experience of oppression with ontologies of partial human being, through theories of race and queer being. With race you need to look carefully at the treatment of Domenego, the Ghanaian gondolier, who only becomes Ghanaian once global relations have reshaped Africa.[18] Impossible contradictions arise. Is it just to confine the issue to one black representative of slavery in Venice. The novel struggles with this. But it also does with queer issues for queer readers.

My heart leaped at a moment that was in fact possibly as accidental a moment as any in a novel Giacomo, Orsola’s brother is responding to the death of their youngest male sibling, Paolo. For me this was the register of a moment of enforced silence as an accident in history that without any doubt in my mid suggested that the sexuality of either Giacomo or Paolo or both was a queered one, but refused to say as is a necessity, Chevalier thinks, of the historical circumstance. She may be wrong Queer sexuality was certainly not all about repression in Renaissance Italy, but I bless ger for her intent. It has to be read as if it were in E.M. Forster’s Maurice.[19]

We perhaps can only be sure of the content of the boys talks at night and the mastery of therapeutic relationship in Paolo it possibly refers to, when we learn of Giacomo coming out as a gay man, and going to live in Mestre with his boyfriend on terra ferma.[20]

Meanwhile, the critics are not wrong that Chevalier continues. As Sarah Meyrick says authoritatively in the opening of her review in The Church Times (Chevalier has comprehensive audiences): ‘TRACY CHEVALIER is well known for her meticulously researched historical novels’.[21] That is why she is not lazy enough to have a literal theory of historical cycles and gyres. The original 1570s plague section has a ‘plague doctor’ in it but the figure is not confusable with the ‘medics’ of her 2019 section and as the authority of a teacher teaching history by empathic means:

It’s hard to finish on a novel that has given joy but let’s return to the quotation in my title:

‘People who make things also have an ambiguous relationship with time. … Its surprising hard to gauge the rate at which time passes – whether it moves faster for others than it does for you’.[22]

The problem with time is one of comparative measures of the effect of time (what gauging is after all) and Chevalier, a consummate, if unshowy novelist, knows that there is no entirely objective gauge of comparative human experience, even of men and women – so full of accidents of history are the lines of development, except the sensitive soul. That Tracey Chevalier certainly is. Enjoy the book

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Tracy Chevalier (2024: viif.) ‘A Brief Explanation of Time: Alla Veneziana’ in The Glass Maker London, The Borough Press, vii – viii.

[2] Allan Massie (2024) ‘Following the fortunes of a family of Venetian glass makers over the course of several centuries, Tracy Chevalier’s new novel bends time ingeniously’ in The Scotsman (6th Sep 2024, 17:22 GMT) Available at: https://www.scotsman.com/arts-and-culture/books/the-glass maker-by-tracy-chevalier-review-a-very-clever-novel-4772785

[3] The Last Runaway 2013), At the Edge of the Orchard (2016), A Single Thread (2019) & now The Glass Maker (2024)

[4] George Dvorsky (2013) “The ‘glass is a liquid’ myth has finally been destroyed” in Gizmodo.com (online) [published May 8, 2013] Available at: https://gizmodo.com/the-glass-is-a-liquid-myth-has-finally-been-destroyed-496190894

[5] Alan Massie, op.cit

[6] Chevalier op.cit: viii

[7] See Flow (psychology) – Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_(psychology)

[8] “It is, and has been for many centuries, the financial and commercial heart of the city. Rialto is known for its prominent markets as well as for the monumental Rialto Bridge across the Grand Canal”. From Rialto – Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rialto

[9] Leonardo da Vinci’s Fascination With Water: The Hidden Theme In His Art And Inventions | Anita Louise Art Available at: https://anitalouiseart.com/leonardo-da-vincis-fascination-with-water-the-hidden-theme-in-his-art-and-inventions/

[10] See Chevalier op.cit: 96ff & 366ff.repectively.

[11] Ibid: 135

[12] Ibid: 49

[13] See respectively ibid: 68, 103, 247, 302 & 347.

[14] Ibid: 302

[15] See Loose Baggy Monsters — A Beast in a Jungle https://www.abeastinajungle.com/archive2009-13/2013/02/08/loose-baggy-monsters

[16] Chevalier op.cit: 63

[17] Ibid: 363

[18] See ibid: 357

[19] Ibid: 136 fir text in photograph below this note

[20] Ibid: 367 – 9

[21] Sarah Meyrick (2024) ‘Review’ in The Church Times available at: Book review: The Glass maker by Tracy Chevalier https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2024/29-november/books-arts/book-reviews/book-review-the-glass maker-by-tracy-chevalier

[22] Chevalier op.cit: viif