The answer is, of course: ‘One, but FIRST the light-bulb has got to WANT TO CHANGE’. This story was told to me when I first trained as a social worker but it was not told in a spirit of antagonism or resistance to what therapy does in meeting the goals that a therapist might help a person who is wanting to change their life to set. Far from it, for it insisted that the power to change was in all of us and all of the time, but that sometimes we feel unable to access the motivation to change.

Hence, when I heard this story when I took a course in motivational interviewing, it justified the course completely. The point of the method is to cause the person seeking help to realise that they were already more self-motivated than they thought. The gist, in short, of motivational interviewing is to discover the inherent desire to change that already exists in the person whose life has become a burden to them. Yet its impetus was a response to the cold analytic, and sometimes aggressive, challenge often directed at patient’s resistant to change by the strict behavioural and more rigid early forms of cognitive-behavioural therapy.

The worst form of the analytic challenge occurred in addiction services where readiness to change was associated with the addict reaching a rock-bottom where the imagined benefits of alcohol or other substance no longer had apparent, and sometimes real, benefits. One of these benefits was known as the ‘secondary gain’ of illness diagnosis – which referred to the ‘abnormal’ attention being ill attracted to the person, a level of attention missing for most in everydaylife.

Another benefit was the idea of refuge offered by the flow of internal chemicals associated with happiness and which feels internally motivated that is sometime triggered by substances, such as sugary starches, alcohol (in the immediate moment of lifting of inhibitory brain controls and before the depressive effect of that particular drug set in), the uppers amongst harder drugs or excess exercise. To expose these as illusions was the function of challenge by means ranging from punishment techniques or the dlighter kinder of scheduled non-response to behaviour you want to extinguish, aggressive or moral contradiction, and leaving the person to their own devices under watchful waiting until they knew and felt they knew that change was absolutely inescapable, to motivational strategies.

The model of challenging resistance in the patient, service-user, or analysand is common to many therapies and helping and supporting practices, but few really talk about what ‘wanting to change’ involves. Addictions, for instance, exist as desires some like to think of as disordered. But the problems of differentiating the word want from both desire and need persists, with some resistance to seeing these words as at all synonymous. In fact, the meaning speakers give them is variable between speakers and sometimes within the same speaker according to time, place or circumstance.

And surely the sane is true of the want, desire, or need to change as people who seek it use the terms. Some like to think of desire as differing from want in terms of intensity and need in terms of physiological requirement divorced from appetite. But these distinctions only matter to bad therapists who think they are dealing with different mental states, not variations in mental state of complex origin and interaction with other forces. In my own view the models of mind that have, as a main intention, tried to avoid notions of psychodynamic drive and unconscious motivation have merely avoided the main issue of desire, need and want and replaced with flatter models of erroneous thinking like the idea of inadequate or undeveloped cognitive process. Ab exception is supposed to be mentalization-based therapy, which specifically addresses the relationship (or mentalized or internalised) model of attachment and relationship to the other. But mentalisation (an empty word if I ever saw one) is a diversion from issues of unconscious introjection and projection, and especially;y projective identification with other sounder and denser concepts in object-relations psychodynamic psychology. It resolves all problems into ‘faulty’ models of knowing mentally (modelling some call it) self, other and the relationships between them. In the end like behaviourism and CBT it is a deficit model of mental illness made for generalisation of treatment approach not specifically derived from what the therapists ‘hears’ from the person requesting help. As a resulting it suits institutions. It may suit some individuals. I have good reason to hope it does. .

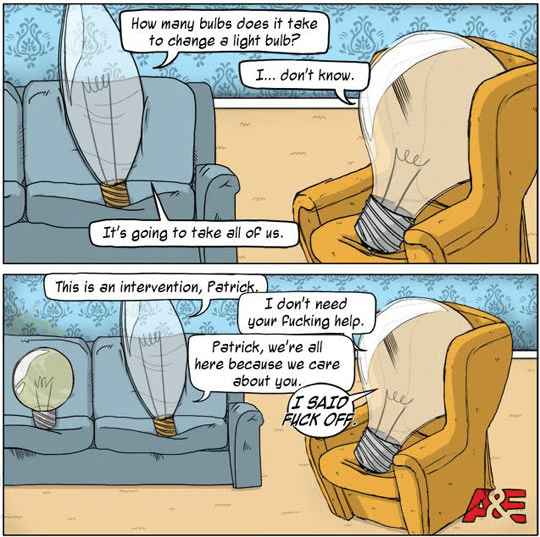

Take the light-bulbs in therapeutic alliance above who try to help their colleague Patrick, who is not only resisting their help but in despair at his wants / needs / desires not being heard and therefore not being distinguished from each other on his terms. This is so much h the case that he swears at them so that they might leave him alone. The two light-bulbs on the sofa feel smug and swap words that use diagnostic and prognostic concepts loosely, speaking of Patrick’s resistance to his own needs but fail to use their perception of his needs to his perceptions of his wants and desires and too easily identify themselves as the carrier of those needs. They can challenge Patrick as much as they want, but until they understand that not being heard is a related problem, they will never support him , turn him on, or allow him to turn himself on to the idea of why change matters to him.

But where i stand can be summed up thus: To be wary is okay but why reject new ideas entirely without trying them?

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx