Philip Sledge pulls no punches quoting his own take on Robert Eggers new film Nosferatu (2024) in a MSN notice detailing the back catalogue of Nosferatu films [in one of which William Dafoe, playing the absurd Paracelsian vampire hunter Professor Alvin Eberhart von Franz in this film, played vampire Count Orlok himself] as “bloody, sexy, and stunning” . (1) Maybe these are empty words, but they remind me of the supposedly damning words used by Victorian critic (and poet) Robert Buchanan to describe Swinburne and the Pre-Raphaelites as poets of the the Fleshly School. It was a take used retrospectively, after Buchanan, even to describe Tennyson, who often evoked the plight of isiolated women women condemned to experience life only as shadows. We could instance the chiaroscuro life of Mariana in the moated Grange or The Lady of Shallot who could think of people, and men like Sir Lancelot in particular, only as ‘shadows of the world‘ in a mirror lest she fell to a death from her high tower at the sight of real male flesh.

Eggers has clearly intended to flesh out his vampire, in the form of Bill Skarsgård, but only by mainly allowing us to see him rarely – at a distance in the shadows the Gothic portals of multiple Transylvanian castle gates (see the collage above right) or in body parts, especially clawed hands) appearing as if from the Count’s point of view) or as a shadow that is either projection or sexual fantasy (as in the poster left in the collage above). When we see the vampire’s decaying and patched flesh, it is only from the back in humping posture and motion over the body of Ellen Hutter, which he penetrates. By the time we see him whole here, his skeleton is wound around the dead body of Ellen in sexual pose so like the Renaissance motif of Death and the Maiden (or Virgin – though our Ellen is no virgin) – adopted by Schubert for High Romantic art. When von Franz shows us a picture of Nosferatu in a pretend Gothic tome with a virgin luring him to his consummation in death, it is half beast, half man in humping motion over the idealised body of a virgin. Indeed a more uncompromised ‘virgin’ is used by the gypsy-peasants in their pursuit of a vampire (of lower class than the count) earlier in the film but her passivity and surveillance by a community of men marks her as so different in class, sexual knowledge and needs from Ellen Hutter.

The film hints that Ellen, because of her hysterical madness, in which she enacts coitus with a shadow and humps her back in the classic form of female hysteria (as observed by Dr. Charcot in the Salpetriere school, whilst Freud was a pupil), was a former lover – and thence of ancient dreamlike high-class, – of the Count from a former age.

Female hysteria as observed by Dr. Charcot in the Salpetriere school, whilst Freud was a pupil there,

Ellen’s sexualised hysteria is only half of the fleshly sexy embodiment of the vampire in this film. In one scene, novel to this film, Ellen chides her husband Thomas as having been himself the willing victim of the Count, and that the Count had also told her that her husband had acted ‘like a woman’ to his approaches (and indeed the scenes of Thomas’ taking by the vampire do show him fearfully receptive like the stereotype of the virgin). And indeed, though me being queer may make a difference, it is easier to see the seductiveness of Nicholas Hoult as Thomas Mutter than that of Lily-Anne Depp as Ellen.

Thomas, Ellen says, can not ‘satisfy’ her as the Count would, which leads to Thomas to take Ellen sexually in a scene reminiscent of a rape. I found it quite horrible and the reading of sex as power hete is hard to reconcile with the rest of the film – as a man proves himself in defence of an accusation from his wife of being a little queer. How different this from Murnau’s Nosferatu of 1922, where Thomas examines two holes near together on his neck that must, he thinks have been given to him by a pair of adjacent mosquitoes in his letter to Ellen rather than a older man biting his neck. This letter is read twice in the film, and the holes remain, in fact, the only effect of the Count’s rather chastely inevident attentions on Thomas’ body.

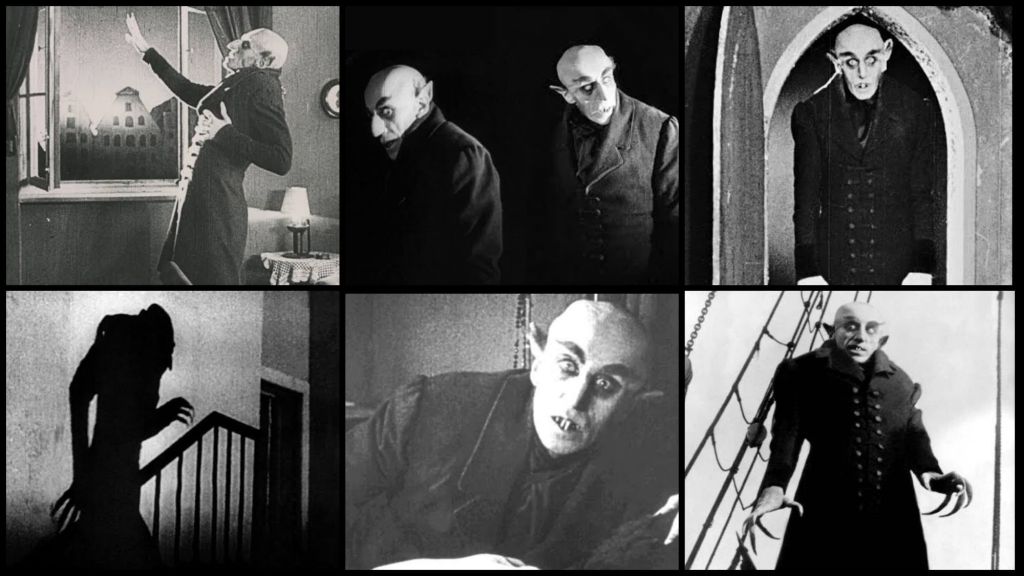

If Egger’s Count Orlok only gets seen in the body, as least without disguising shadows, latterly in the film, this is not the case in the 1922 classic, F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, as the collage below shows. But the body is never naked, as Eggers’ Count is, even with his phallus evident in the shadows. Even when he arises from the virgin bed of Ellen and disintegrates in the sun after a night of passion, which Ellen survives and does not appear so keen on except in role-play as in Eggers, he is still fully dressed as a nineteenth century dapper gent (top left in the collage).

The scariness of Murnau’s monster was a surprise to me after long knowing the famous stills above when I saw them in motion on Monday night streamed on Amazon Prime. I had, from the stills, thought this vampire was more fantastical and perhaps even more funny than terrifying. But seen as a moving picture all that changes – even the famous scene of the movement to Ellen Hutter’s upstairs room of the dark shadow, not the substance, of the vampire raises the hairs on your neck. When Ellen’s door handle is tried, that too is done by a vampire’s shadow hand-cum-claw not by vampire flesh, although less is made in the Galleen script, thought it is there for Eggers to amplify, of the notion of nosferatu as shadow rather than substantial body.

In his prime seduction in the film, of Ellen [the equivalent of Mina in Bram Stoker’s book] what climbs the stairs to her room, and even touches the door handle in the best of these moments, is nothing but a shadow not a thing deemed of flesh and fleshly. In his seduction of Ellen, there is little blood apparent here or elsewhere – the teethmarks of the vampire being delicate and small with only a dried residue to show their use.

All of this is mimicked by the 2024 film but without being equally fearsome. The shadow of the vampire is in Eggers’ film overly fragmented by being seen through partial windows or inner portals rather than being the enlarged shadow of the whole beast rising the stairs and larger than the door into which he will enter into Ellen with no sign of a body creating both beast and its motion. The shadow that opens Ellen’s door in the 2024 film is too close to be frightening, such that we see Ellen, when it opens, in a stage voluptuous welcome to the monster, our attention us deflevted from the monstrous, perhaps aping her willingness to be part of the vampire’s consummation, or perhaps not.

I never thought of the Hammer versions of Dracula, played by Christopher Lee or even the lush later version played by Gary Oldman (which also implies a link of love between Mina Harker and Dracula from a past barbaric Gothic life as Vlad the Impaler) as frightening either in the same way.

The fear Murnau conveys is something to do with his monster’s rigidity and the characteristics in it of a cross between a feral beast and an overgrown pixie with fangs. For though this monster is undeniably ugly and awkward in stance and motion, its terrifying effect has a lot more to do with how he achieves his magnetic effect by virtue of his almost various forms of surprising motion – and not just the famous scene where he rises like a rigid pole to the vertical from his coffin in the ship’s bowels. Murnau’s Count Orlok has almost no body to speak of, just an absurdly puzzled face (bald-headed with pointed uneven teeth in a rather uncontrolled open mouth, big ears and a crooked nose- so much so that the stereotype seems for its time in Germany anti-Semitic), long-fingered hands with even longer nails. There is something sad in Orlok’s longing for Ellen, like a little boy awaiting the return of his mother at a window.

The most blood in the 1922 film is that which gushes, relatively speaking, from Thomas’s finger when he cuts himself on a knife used to cut bread on his first meal in the presence of the vampire at the latter’s castle in the supposed Carpathian Mountains. I have to say Nicholas Hoult cuts more decorously and the nick he creates is just that, even if it leads to an offer from the Count (‘I can help you with that’) that feels semi-sexual.

Murnau’s Count Orlok I noticed only just fits the doorways of his modest castle, whilst Eggers uses much wider portals to frame his Orlok in the large.

Nevertheless Murnau came into his own in his film with Max Shreck as Orlok in the boat scenes, seen from below. Orlok’s surprised innocence still seems slightly funny, except when we see him move, but looked at below he is more monstrous than any other player of him, including Klaus Kinski and Dafoe, who played look-alikes.

You only have to consider Robert Eggers’ back number films, including The Northman, to see that his interest in the necessity or otherwise of toxicity in masculinity is lifelong but that is not the main problematic issue in Nosferatu. I think that problem is how the director’s concern with masculinity reflects on the construction of his female characters in the film. In this film, in my view, it reflects badly.

Maybe I have a bias because I found Lily-Anne Depp’s performance entirely unsatisfying, but there is more to it than that. The details from stills below show the nineteenth century bourgeois setting allows Eggers to be lazy about how to represent women without avoiding nineteenth century female stereotypes and most of all the pernicious binary of the ‘angel’ and the ‘whore’. Women who express the sexual eitjer not at all or as a symptom of hysteria, a diagnosis that died out after Freud and Breuer’s essays on it, or through the excess emission of bodily blood (a reflex of male fears of menstruation), are very much the whole range of women in the film. Depp plays the hysteria well and is physically very athletic, but there is no depth or nuance to redeem this from being the male construction it always was. In the collage below, Ellen and friend , Anna, walk bonnetted through a graveyard in sand dunes (very like the scenes used by Murnau) that their claim to sanctity seems justified. But what lies beneath the cover of sand and crinoline alike is the bloody demon whose blood runs from every orifice in the inset picture oc the collage.

This is why I think the first half of Eggers film satisfies so much more than the second where Orlok arrives in Wisborg to claim his Ellen. The story of heterosexual pursuit flags and descends into stereotypical hysterics that do little for the film: especially the inclusion of the plump daughters of the shipping entrepreneurs, the Harding’s; whose dispatch by Orlok seems meant to be enjoyable to the audience, so grotesque are these flounced girls. For the film does, like nineteenth century novels did, equate women with a suppressed fear of their own capacity for fearful disorder – like those Harding girls who fear going to bed without daddy. The whole of the second part of the film, is mainly (but not only) about women being ‘under the shadow’ (something a peasant woman warns Thomas against early in the film) of Nosferatu. Ellen is under that shadow, but only in order to merely await its bodily emergence and consummation. Hence, the words of Orlok I quote in my title: ‘Soon I will no longer be a shadow to you’.

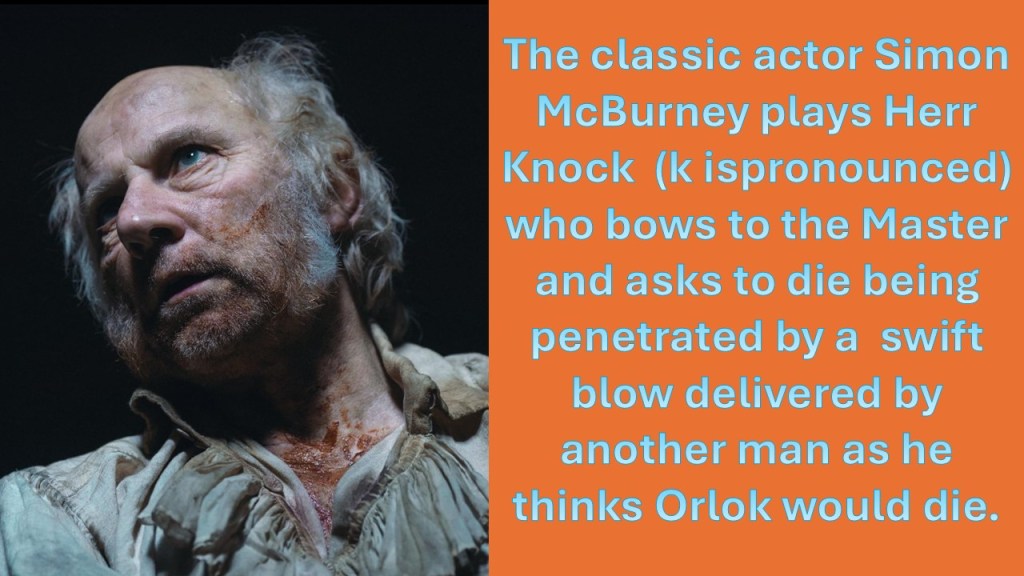

The first part of the film is as compelling a study of coming into manhood as you can get and is played very differently to the film in 1922. In 2024, Thomas Hutter’s employer, house-agent Herr Knock (the k is firmly pronounced in the film) , played by that masterful actor Simon McBurney, is himself a shadowy figure clearly aware that he is sending his employee to seduction, rape and murder. It is not the case with Murnau whose Knock is a rather comic character and may be as motivated only by gain as he easily persuades Thomas he will be. Murnau’s Thomas is full of bluster consequent on expectations of money, a new status in his firm and occupation and male camaraderie that allows him to act like a man on a ‘jolly’ in the Bavarian inn, rather a seducer than than the seduced, only to find himself surprised.

Eggers takes another German Romantic option, making it clear that, at least when alone, his Thomas is a Romantic sensitive, almost modelling himself as Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 painting, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (see inset below).

This Thomas is a man of sensitivity and neurotic fear – perhaps even feminised as Werther is by Goethe in The Sorrows of Young Werther. Whether feminised or not – he is like Murnau’s equivalent in use of a vanity mirror after receiving Orlok’s attentions, except that Eggers has him shatter this mirror in terror. Very often Nicholas Hoult plays Thomas as if not only very afraid but also beautifully vulnerable; so passively reduced to motionlessness that the camera eats him, as he sweats sexily, or bleeds from Orlok’s teeth wounds – in his chest not his neck. The fearful stance is unashamedly played as what, to a monster, would be an invitation to come and get him. ‘I am unarmed and defenceless’ is the statement it advertises. He is even sometimes pressed against a wall.

By the second half of the film Thomas is recovered – von Franz says that he ‘is not under the shadow’ of Orlok like his wife, though the nuns in Transylvania thought he was and not yet cured, even when he left them. This is necessary for the plot because Thomas must regain his virility in Wisborg – the turning point seems to be Ellen’s taunting him to take control of her sexually and that is the worst scene in the film ideologically. But other men do succumb to the feminised passivity invoked by Orlok on them – sailors on the ship Orlok travels to Wisborg on, for instance, the sailors manning a ship owned by Harding – and even other men .ore central to the story. In the Murnau film Herr Knock seems to be carried along by submission to old wealth in Orlok until he assumes the role of Renfield in Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula – eating flies, spiders and eventually trying out men and is scapegoated by the town for Orlok’s crimes. In Eggers version, Simon McBurney bows to the Master predator in every appetite concerning flesh and asks to die being penetrated by a swift blow to the heart by a hard baton delivered by another man as he thinks Orlok would die.Knock is unmanned entirely, taking the role that Thomas must not.

But the most puzzling feminised character is in the queer madness of von Franz, as played by Dafoe, a Paracelsian to the absurdest limit. In Murnau’s film, his equivalent is named Dr. Bulwer and the latter teaches a kind of natural science (comparing a vampire to a Venus fly-trap he is showing to his students in the act of eating a fly) rather than attempting, as Dafoe does, to turn lead into gold, the classical alchemist’s trick. Dafoes’ vampire hunter becomes delerious and hysterial (as Bulwer never does), dancing on the graves of vampire victims and Orlok and rather upsetting the now rather settled bourgeois gentlemen, Harding and Hutter.

In the end, one supposes that once Ellen is dead, Thomas Hutter will take to some enterprise and master the necessary tasks of German capitalism after the devastation of the trading city of Wisborg. After all, Orlov gives him the necessary capital, as if old money were passing to new metamorphic uses. However, for me, it seems important that Thomas’s right of passage needed to be represented by the old trope of the crossroads so associated with evil and vampires in particular. The scenes that one loves are those in the Carpathians, associated with carriages, for Thomas learns that nothing is worth going into the past for even in respect for elder aristocratic greatness.

He learns to be the new man and will (will he not?) even overtake socially the over-cocky friend of his, Freidrich Harding (played by Aaron Taylor-Johnson), once his patron, moneylender and social superior – for the latter is ruined financially at the end of the film. Moreover, it must come as rather a blow to Friedrich to discover at the end of the film that his shipping wealth is based on a town that is not coastal except in Murnau’s transferred imagination. As in 1922, of course, there is no sea between ‘Transylvania’ and Central Germany. LOL.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxx

___________________________

(1) Philip Sledge MSN 14th January 2024 After Watching Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu, There Are 3 Other Versions Of The Vampire Movie I Think You Should Watch (use link to see original).