The i newspaper collage above promises one minute with Jenni Fagan. It is a provocative statement. It’s almost problematic in its offering of the writer to any reader. This blog was stimulated as I was scanning my bookshelves in order to catalogue my personal library. The last sequence of shelves I have attempted has been engaging me personally more than usual, starting with my very full Iris Murdoch and A.S. Byatt collections. These have raised many memories.

I was taught by A. S. Byatt in her stint as a teacher of literature at University College London and became a friend. I have read again some of the cards and letters that survived that time and also recalled a story Byatt told me of mentioning me to Murdoch on a visit to Oxford. Murdoch, Byatt told me thought about my name a little before she jingled: ‘Bamlett. Hamlet. Bamlett. Hamlet …’. I say this not to drop names, though it is often taken this way, but to explain why the knowledge of knowing one’s writing heroes in person as it were has not seemed to me a thing to value in itself as a trophy, but as a kind of relationship. In truth, reading the one Byatt letter extant to me, I had forgotten how well we knew each other, though even now almost certainly over-estimate the importance of that relationship, which, after all, like all others by their mature merely pass away with other mutable things.

Once settled in relationship with my now husband (we married only in January 2006 for it had just become legal to do so but had been together since we met in Leicester in the 1980s) my interests had changed. I was training as a social worker after a period of various jobs and personal breakdown around them (not unfortunately for the last time) and my interests veered more to left politics not literature.

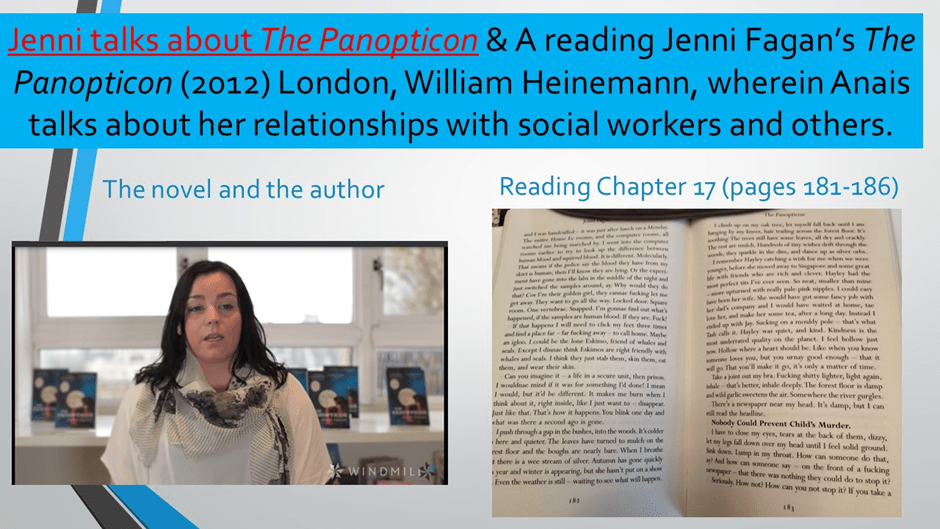

The story is complicated and fragmented, but it eventually ends, after doing another degree in psychology, in teaching and lecturing in psychology and thence to teaching social work. I was once Subject Leader for Social Work at Teesside University. During that time and following depressions of a severe kind, I took up reading literature again and collecting books of modern writing. Geoff and I went to the Edinburgh Festival every year, and I scoured the Guardian Arts pages. It was there I first heard of a new writer, Jenni Fagan, and her novel The Panopticon, highly recommended by poet Andrew Motion, who had supervised its writing on a writing course.

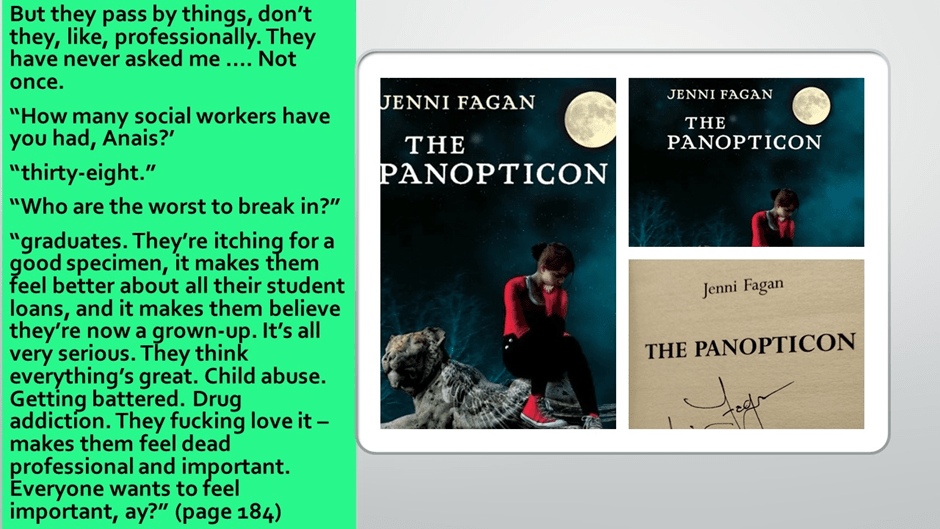

The Panopticon was everything I wanted of a novel. Based on Fagan’s own experience of institutional care on the cusp of the care and control systems of Scotland, it took as its focus Bentham’s idea of the Panopticon – a place where jail supervisors could SEE everything that occurred and which linked criminal and mental health rehabilitation and care to surveillance and experimental control, as prompted by the treatment of the idea in Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Here was a vision that I could relate to – one in which politics, experience of power and the subjective, even to the level of day-and-night dreams, were inseparable, and story related to social contexts and social outcomes without loss of imaginative power. In truth, Byatt felt similar things, but they were contained in a view of the world was ultimately bourgeois and as afraid of change deriving from what was perceived as the masses as being sympathetic it.

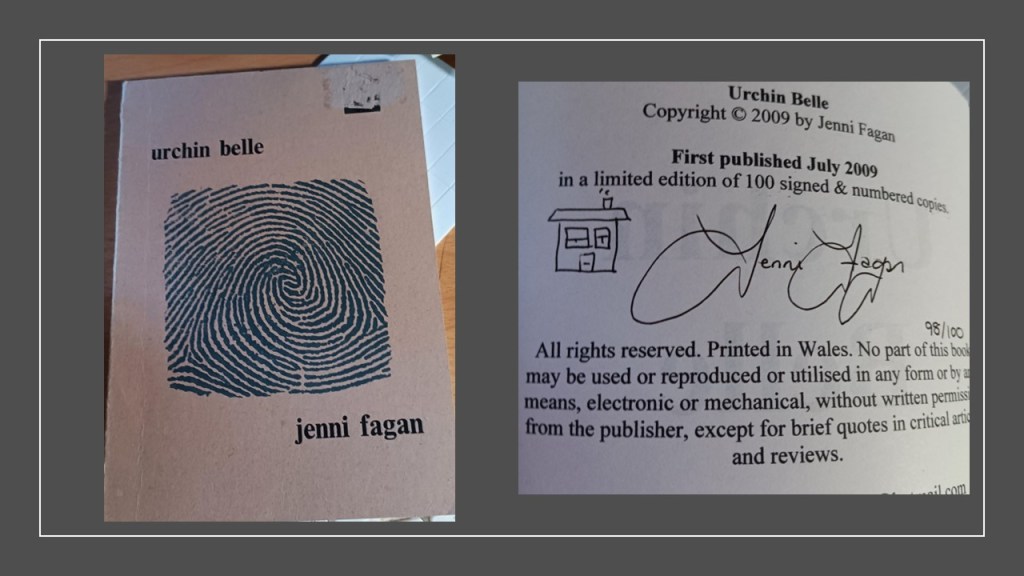

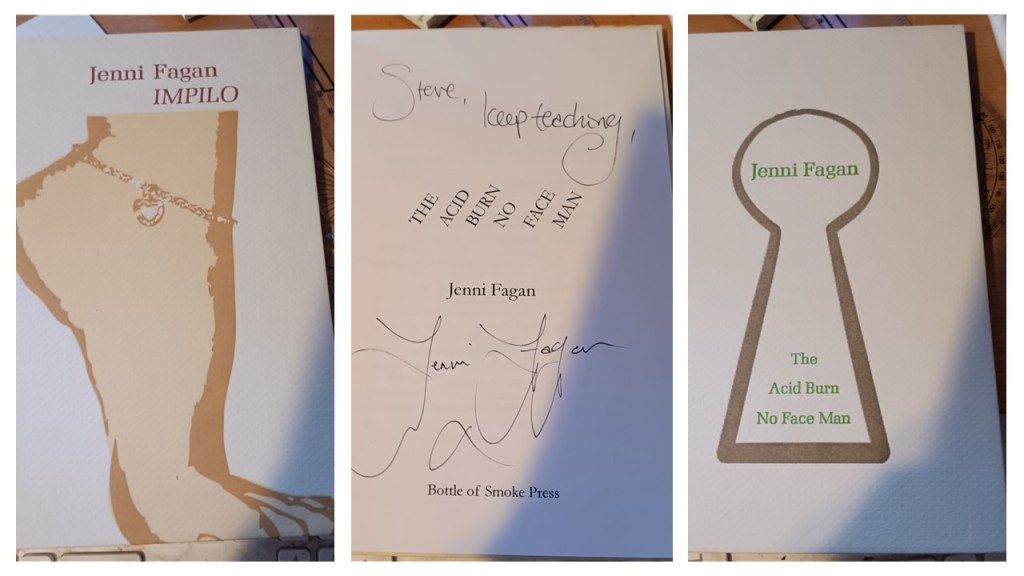

To such a view, Fagan’s literature would eventually put up two fingers and embrace newer truths. I saw Fagan at Edinburgh, and as she signed my book, I asked if I might teach it to social work students. In Teesside, having stepped back as Subject Leader, I started a seminar on social work as reflected in literature using Pat Barker’s The Century’s Daughter (with its queer social worker protagonist and which I read when it was called Lisa’s England) and The Panopticon, and a set of early Fagan poems I selected from urchin belle, a 2009 collection in a limited edition I had purchased via a dealer in the USA. The course was an immense success. When I told Fagan she insisted on adding a drawing to my copy of urchin belle (a drawing of a house, which I believe she told me was an important personal symbol to her), it already being signed:

I had it seemed formed a fairly easy-going relationship with Fagan, and it developed when I asked if I could blog on her, having taken a MA course on the use of digital technology in teaching with the Open University, with whom I was then teaching Psychology and Foundation Neuroscience and being required by that course to try blogging as a teaching tool, and she agreed. Many blogs followed. As I name them, I will link to them. It was my practice always to send them to Fagan for her information, given they were on her, with a statement that I was not asking her to read or respond to them.The first was in 2016 and related to that year’s Edinburgh Festival where I attended a seminar / event she led on the Scottish novelist, of whom I had never previously heard, Jessie Kesson. That seminar led to me reading and collecting all of Kesson’s oeuvre. Here is the relevant blog-link. It was one preparing myself for the Kesson event. That blog appears as later resissued in another blog home after I left the Open University – terrible meddlers/censors of blogs.

The blogs followed thick and fast, relative to the speed of books emerging as I wanted to record my enthusiasm – for, for instance, in 2019 the tremendous story Pluripotent, which combined my interest with biological neuroscience with work that focused on marginalised working-class, women’s and queer voices. Having sent it to her Fagan sent it on to the editor of Smashing It (the reference is to smashing ‘glass ceilings’ that hold us down) the volume in which it appeared.

Then can the poem Truth: A Poem in Six Parts in the same year, with Fagan’s photographs of her tour of America in which she sought truth only to be told, as she says in a printed epigraph ‘that it was the last place I should go looking for it’, and this only during Trump’s first presidency. The next novel I blogged on was Luckenbooth (2021) but it is a blog full of doubts about the security of the truths behind my fascination with it, it being a bit removed from the magic realism of earlier novels and verging on the surreal.

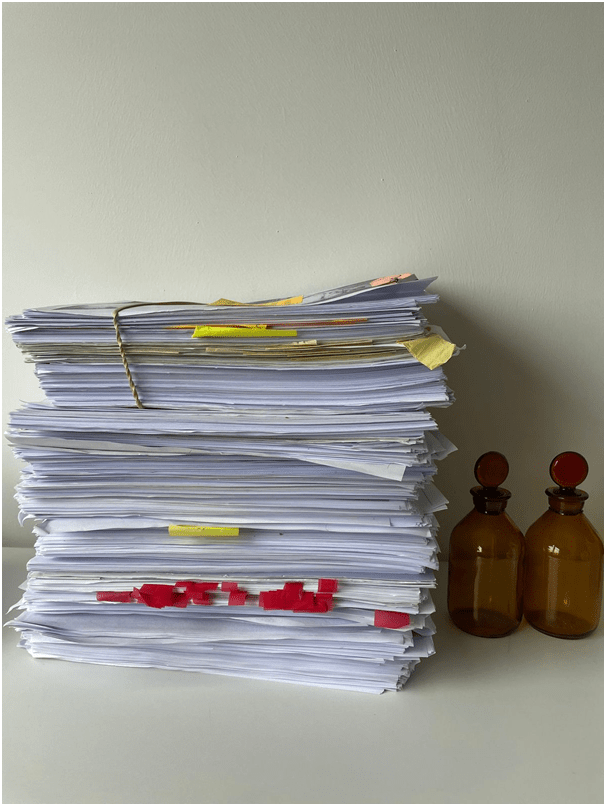

2021 was the year the long awaited memoir of Fagan’s first hove into view. Fagan would tweet about her preparations and I remember a Twitter conversation with her where I mentioned Janice Galloway as having done wonderful things with the child voice in memoir, as well as collecting pictures from her tweets – often of piles of social work files, like that below, that had impinged on her birth and life.

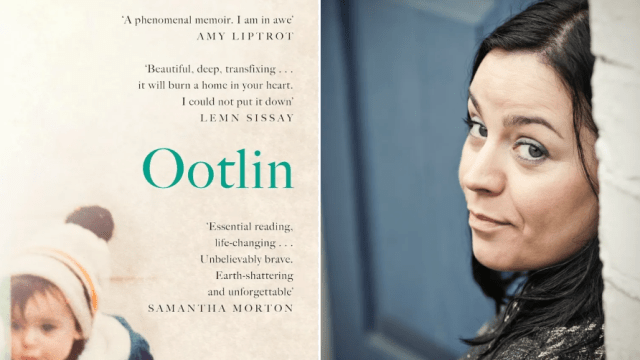

At the 2021 Edinburgh Festival she worked and took part in a dramatised reading of a ‘radio play’ (based on one by Jesse Kesson) where the idea of the Ootlin was first aired. I wrote this up. Fagan read it and asked me to remove from photographs of her on stage for the event, which I happily did, though I treasured the memories they had prompted. She also corrected me about how I understood the term ‘ootlin’. All this was an honour – it felt like the margins of a distant but good relationship. Here is the blog as revised

From 2021 the play I saw and heard haunted me. I desperately wanted to read a work that so much showed what a literature of liberated freedoms from social and literary conventions might be: a text that stood for telling a new truth, but the longing, like many others might have become inappropriate and full of projective identification for the figure of the lost soul so much Fagan’s theme. The book was not advertised to come out however befre 2023, and eventually was not formally published until 2024.

In the meantime, Fagan followed other fascinations – those of identification with the witch for instance (present since the volume of poems called There’s a Witch in the Word Machine, which combined the fascination too with technologies of word production, from typewriters to those more digital.

What followed in 2021 was a stupendous ‘historical novella’ (though Stuart Kelly was as usual peevish about its historical reality) Hex. Here is my blog on it and Kelly. I read it hungrily and searched for the spaces where Jenni, as I thought her then, might be reading it. All I could contemplate in terms of distance (I live in County Durham) was the Aye Write festival in Glasgow where the book was being read by her with a chance for questions and in the gorgeous Mitchell Library. The event was fascinating. Two radical feminists attacked the book at the question time for its negativity about progress in the history of women’s lives, raising a fine riposte against these women’s true target, transgender ideology. It was another moment of wonder at this writer for her politics – a queer feminism so profound it was often misunderstood. Queuing to have my book signed I commiserated with her on the attack and went on to supper alone in a South Indian restaurant in the city. Actually, I did communicate again with Fagan that evening. she communicated by Twitter to say how frightening was the train back to Edinburgh, full of drunken bad behaviour. I empathized.

In the same year I blogged on a new volume of poems called The Bone Library based on Fagan’s residency at Summerhall in Edinburgh, the old Veterinary College which she spent reviewing the collection of bones (this is also referred to in Luckenbooth, in which she used the history of the place to explore deep themes. Here is my attempt to articulate a few of those themes.

As 2023 I was impatient and nervy, again that’s inappropriate but I did not know it at the time,for the work. I had, from retirement taken on some teaching in Psychology at New College Durham, and had revised the Social Work Psychology course. I taught little of it before leaving – unable to take any more than in the past the administrative process of modern higher education. However, you can tell my excitement about what Fagan offered to social work knowledge in her past and this upcoming book, from the draft lecture-set I prepared on Attachment Theory. I link to the blog here. I also attach two slides from exercises for the lessons.

2023 was an odd year. In a moment of Murdoch like fascination with loving across boundaries, I had fallen in love with a younger man, in his early fifties and had turned this into a relationship that did not threaten my husband’s primacy in my life but, like all such events, it was not easy. During 2023 the young man abandoned Geoff and I, after two and a half years, and cut off all communication, and, to make things tragically worse died of his alcoholism before the end of the year. I was highly stressed. Nevertheless, I was looking forward to seeing Fagan at Edinburgh in her August launch of her book (I booked for it in June), and all three of us had tickets. Just as the young man withdrew, Fagan cancelled her launch event but there was no news of whether the books were to come out – I had mine ordered (as a signed copy) at an Edinburgh independent bookshop (Toppings). On the day of publication, I went to Toppings, and they informed me the book was not to be published and that there was no news of when, or whether, it might be.

There was a perfect storm of loss in these events. On my way to the event my doctor in Crook had called me to discuss the suicidal ideation of which I had informed him. All this melded. Nevertheless Geoff and I met a bookdealer (mainly of second-hand works) at the Festival who had copies of Ootlin, brought there to be signed by Fagan, and was, rightly or wrongly, prepared to sell it to me at cost-price.

Reader, I bought it. Once home from Edinburgh, I blogged on it – as usual, sending it to Fagan. It is an excuse I know but I had not thought that the the cancellation of the event also touched on personal events in the author’s life – in her next publication (of poems in 2024) she makes it clear that her estranged father had died. I refer to my construction of this in a blog reviewing her raw, visceral poetry set A Swan’s Neck On The Butcher’s Block of 2024.

A link to the blog is here but below is what I wrote and how I constructed its back-story:

But this volume is painful, but more so for its embodied pen (or typewriter) because it deals with loss it can only hint about and dare to be understood, but DEFENSIVELY fears it will be misunderstood. I capitalise ‘defensively’ for that is a feature of the poems sometimes. It deals with the past of an ‘Urchin’ and ‘Ootlin’, bereavement of a father less almost unknown to her during the time he might have been there for her (see Memorial and Winter Solstice), of a mother who was, in the end, a victim, but who left her only the traits, or so ‘they say’, that makes people recall her as ‘a fanged thing’. The lyricist does not want to be a victim though she carries with her what her foster mothers saw as ‘madness’ and against all the barbed nuance of all this she tries to defend herself.[9] All of this is bound up with the delayed publication of Fagan’s memoir Ootlin, of which:

On publication day my books sit in a warehouse in the dark, very much alive, deadly as they ever will be,

Whether I was right about this or not, it shows how trapped I was myself in the loss that occurred of my relationship – distant and minimal as it was – with Fagan. This is the outcome of sending it to her. She told me that it was a difficult time but that she would see it, since it was written. unfortunately it arrived with her on her birthday. She was most concerned with HOW I got the book because it was still under publisher’s embargo. Since that involved another, I would not (and still won’t) give the name since it is not in the public sphere. The blog I wrote is linked here.

I bought that toy Hulk in Crook because of my fascination with the image of that angry man as it appears in Ootlin. But though I attempted to apologise for an upset I did not know I was capable of, or could have, caused (not knowing enough) Fagan was angry and demanded I give up an email contact she had given me. I did immediately and took on the whole story as an additive factor to the story of loss I was feeling in my life at the time. The book Ootlin has now been published before the poems I refer to above. I now have that first 2024 edition, which sits in my collection next to the extant 2023 one,

I have roughly compared them. There is a slight difference. Chapter 11 has been rewritten. It originally consisted of one page (page 46) but is now two (pages 46 – 47). It originally told of what seems an event from a foster mother who was forcing the child to eat what she had rejected using what feels to be methods that are very crude – including a head down the toilet. In the new writing, the event loses specificity of reference to what feels like torture and now only covers the drama of wills between ‘mother’ and child. Because a page is picked up here, economy of old page use produces a new break in the remaining narrative so that the book ends with two pages short, although it also has removed from it an ‘Author’s Note’ (pages 323 – 324) of the original edition. That this change was necessary suggests yet another story about why the book was cancelled from publication – even after it had received at least two national newspaper reviews (one by the awful Stuart Kelly referred to in my blog) and been excerpted by Fagan in The Guardian.

But that all of this has cost me a ‘distant’ relationship to a wonderful person I regret. No doubt my behaviour was socially inept, as Fagan told me it was, but it was not ill-intentioned, but, as they say, ‘roads to hell’ are often so paved. And swans remain swans, even after swansong.

With love

Steven XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX