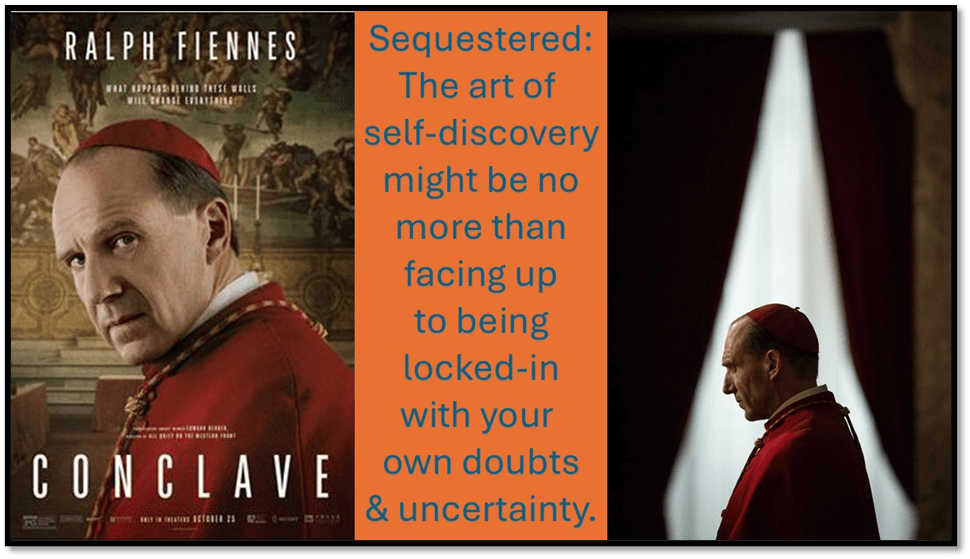

Sequestered: The art of self-discovery might be no more than facing up to being locked-in with your own doubts & uncertainty . A reflection after seeing Edward Berger’s film Conclave. [The film is directed by Edward Berger and written by Peter Straughan, based on the 2016 novel by Robert Harris].

There is a truly impressive moment – of acting, cinematography and film direction – where as a result of a terrorist car-bomb outside the Vatican (one of the series of terrorist incidents we shall find later that are shaking the whole globe as the cardinals sit in judgement of their own souls), a hole is blown through the fabric of the building (maybe even just a stained window, and a shaft of light falls in on the secreted proceedings. The proceedings are those of a conclave that would elect a new father figure, a Papa or Pope, to lead, guide and represent them down to their innermost being. The shaft seems to fall on Cardinale (the Italian form of the role feels better to quote than the English) Lawrence (played by Ralph Fiennes), Dean of that conclave. He is a man riddled with doubt and uncertainty, but defending these as being themselves the pillars upholding a more true form of faith than arrogant self-belief in the unchallengeable rightness of a centuries old institution of Catholic faith, represented in this film by the Venetian Cardinale Tedesco (brilliantly embodied by Sergio Castellitto).

Tedesco is old school – he believes in the unshakeable rightness of the Catholic Faith and the need to uphold its dogmas and even its prejudices, against other faiths – notably and most in focus Islam, which is associated for him with the terror plot in the film, and tolerances of human diversity beyond the norm. He is the candidate for Pope the modernisers fear most (best represented by Bellini (Stanley Tucci truly magnificent in that role) and who had rejoiced in the contemporary wisdoms of the old Pope, but now dead as the film starts. Cardinale Tremblay is a possible contender who might suit the modernisers, if only with some trepidation on the latter’s part at the man’s subtlety in the seeking of the Papacy.

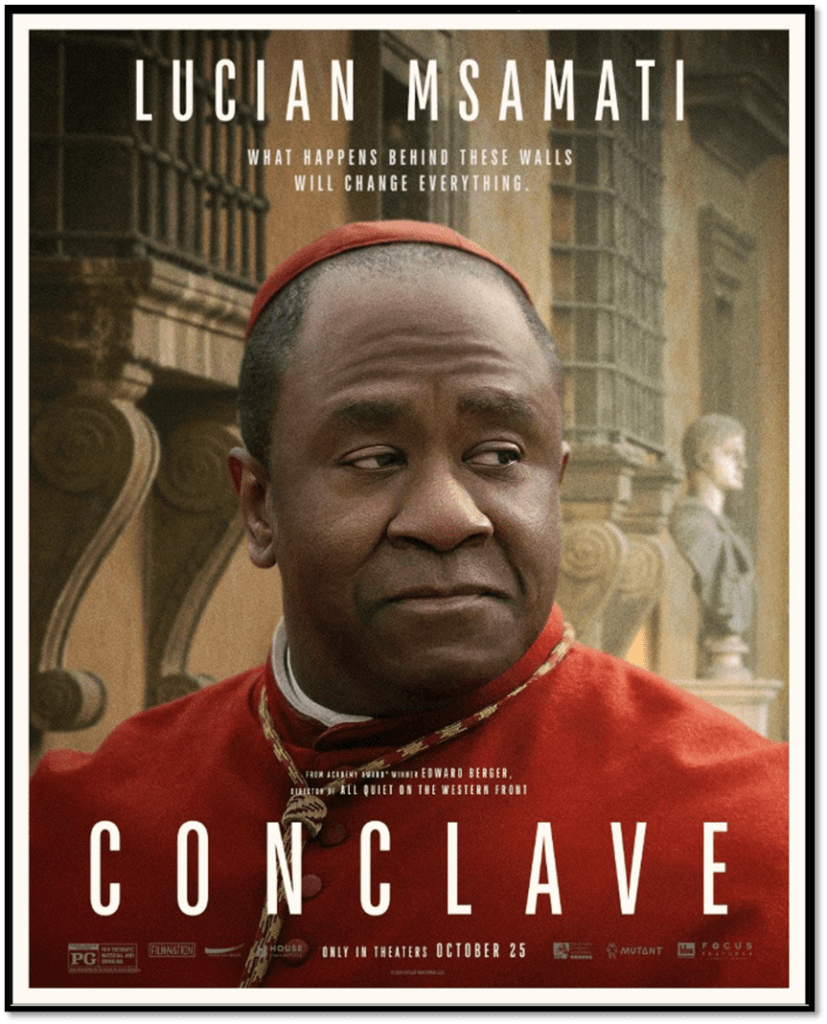

Against him the other obvious candidate is Cardinale Adeyemi. Adeyemi is a crucial role but one that underlines in the main the mechanisms by which black Catholics are rendered invisible outside of Africa in the Church. Tremblay destroys his credibility by ensuring the presence of a nun, once a secret lover of Adeyemi and the mother, perhaps, of his child, at the conclave. Tremblay blames the act on the dead Pope, for he cannot speak on the matter. To see Lucian Msamati, fresh after seeing him in Waiting for Godot on the live stage (see the link here for the blog) underlined this actor’s brilliance for me but also the deficiencies in the roles the film industry throws up for great black actors. Cardinale Adeyemi is there mainly to be destroyed, and perhaps (in the message of the film – for good reasons. The liberals in the conclave (Bellini in particular) see his views on homosexuality making him more as feared by them politically as Tedesco and with no hope for the papal role in the modern church had ‘he not been black’ as Father Bellini says to the Dean of conclave, as a sympathetic friend. The inbuilt tokenism of the appearance of black actors talks through this coincidence of story and casting.

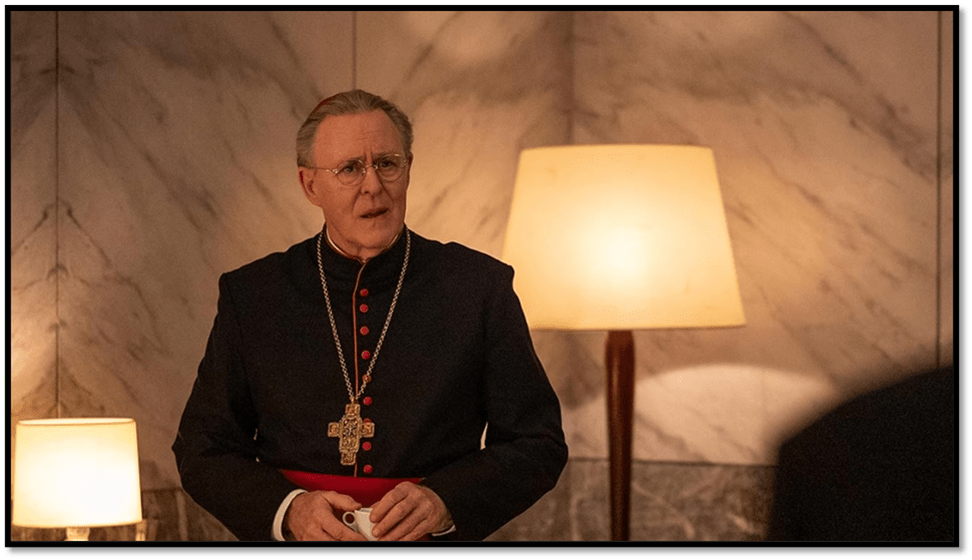

Tremblay destroys Adeyemi and is destroyed in turn. His sin – simony, the act of buying or selling church office – but his corruption goes perhaps much deeper for we never know how true is self-defences are. John Lithgow is suitably subtle in that role. His searching for greatness he feels h deserves is brilliantly and fairly represented, his degradation at the film’s end, even more so. His role underlies the fact that the most sequestered, the most locked-in of judgments is not that of a papal conclave, locked behind huge medieval doors to decide on a fit representative but those things decided behind the closure of human souls in human bodies.

If Tremblay and Adeyemi have secret selves and secret hungers – in the past, present or secreted ambitions for the future, so do other cardinals and perhaps most of all, Cardinale Lawrence. We do not know if Adeyemi or Tremblay, or even Bellini (despite protestations in which Tucci is most brilliant, lie to themselves about their ambition and their uncertainties about their own fitness to attain them. hat is clear is that Lawrence does. He emerges late in the process as a viable candidate for the Papacy. He enacts his surprise and belief in his unreadiness but pressed by Tucci, we know he at some point has already decided on a Papal name for himself – Pope John. There are dark passages inside Lawrence. They seem present but hard to name when he breaks the papal seal locking up the private rooms of the old dead Pope to uncover what that man knew. Isabella Rossellini, playing Sister Agnes – in charge of domestic arrangements in the Papal palace and for the conclave, enacts those doubts we have of him when she presses her ear to the door of that locked room as she observes silently that Lawrence has turned out the light within, having perhaps heard her. There are a tissue of symbols of hiding and shadowing the inner self here.

Agnes represents at that moment all the faith they may have in the character of Cardinale Lawrence, as she also represents our simultaneous fears of being betrayed by secret and hidden motives in men – always men (for , as she says, she and other nuns of the Curia are trained to be ‘invisible’). And this perhaps is why so much has been invested in Ralph Fiennes as an actor of that role – whose very face seems able to shut up and open out his soul but most often is compromised by complex multiple emotions playing out all at once.

.in his role of Dean of conclave his guardianship of the sequestration of the conclave is absolute. He must know what goes on outside the sequestered rooms of the conclave but must seek to hide it from his colleagues. Certain of those external truths he may hide from himself. Nothing is more clear than that the Papacy and the institutional dressings of the Papacy, as clothes, building or interior décor are meant to hide things and keep secrets, even formally as in the vital role in the film of the appointment of Cardinals in pectore, an act of secret appointment reserved to the Pacy that occurred before the film and hides most of the incredible twists and turns of its plot. Initially about the relationship of Catholicism to Islam the reasons for in pectore appointments strike deeper into the film’s explorations of sex/gender, toxic masculinity and the role of interiority in faith, life and conduct, after all the literal meaning of the term is ‘in the breast’. It would be hard to write more of this without spoilers that really might spoil the film for you. So I will try to be careful here and elsewhere where that that is true.

One star of the film in this respect is the Vatican itself. Its architecture of facades – even great art acting as facades (and particularly Michelangelo’s fresco of The Last Judgement) as above – emphasising both the closure of the institution and its hidden places. The Vatican fades are bathed in light and this makes for beautiful scenes of cinematographic choreography, my favourite being the cardinals moving about in the rain with identical white umbrellas.

Whited sepulchers though have many shadows. This kind of chiaroscuro defines the beauty of the film.

And art in ritual action, vestments (wardrobes feature deeply in the film), painting on a walls and the architecture of doors, floors and ceiling, even of articles used in liturgical processes, hide many meanings other than sacred ones, though underpinned by those.

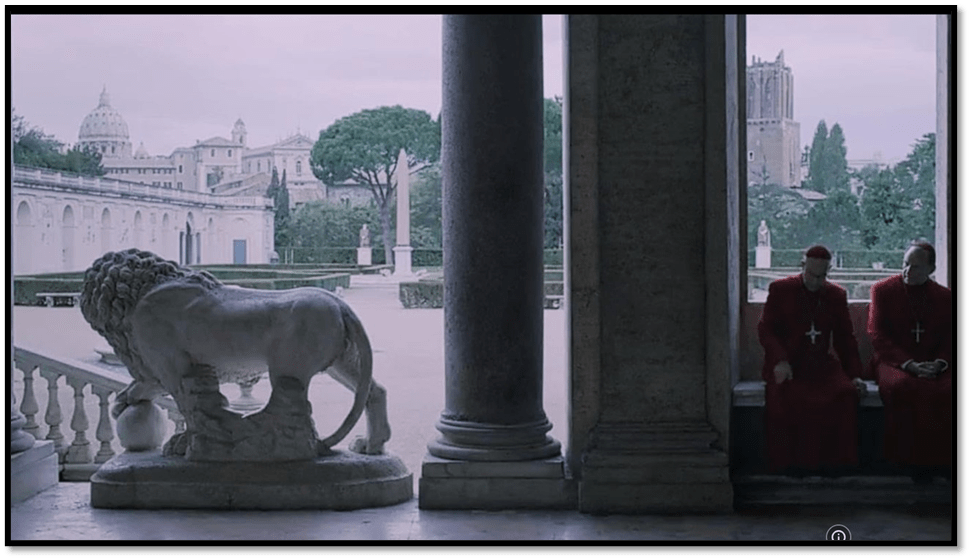

But the Vatican has its dark places too that resemble the Gothic and semi-pagan heart. The scene blow is crucial enough for me to stay mainly silent about.

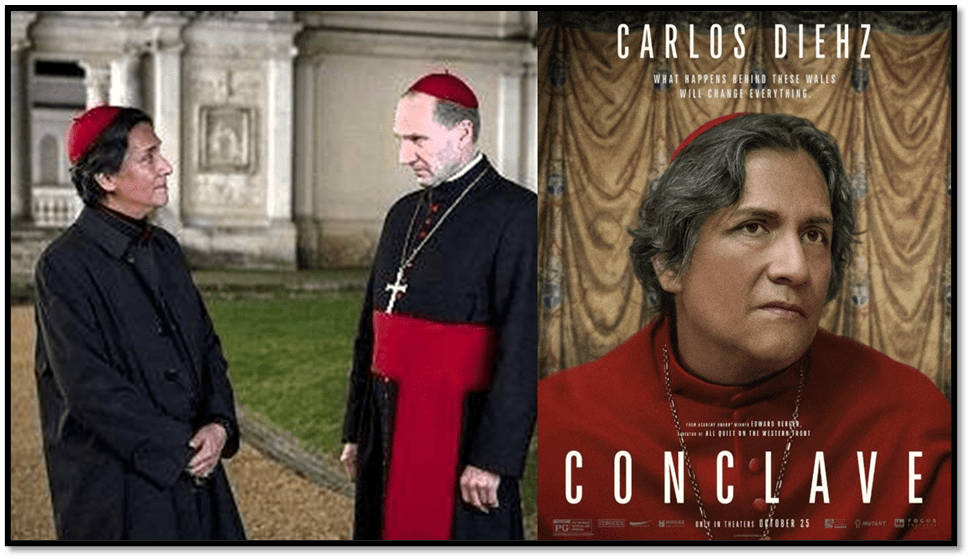

The one below even more so, where a pagan image obtrudes into the darkness from the floor under the tremendous figure that is the in pectore appointment, cardinal and Archbishop of Kabul in Afghanistan, the Mexican Cardinale Benito. The performance by Carlos Diehz is both beautiful, defining and wondrous, but here again silence must fall.

That this scene is in he dark and more sequestered than others matters to the way the film handles interiority but what is more clear about the film is that it insists that secrets are kept by darkness but more often in the full light of day and in the reflected glare of supposed splendour of the institutions of the status quo supported by an end-stopped history, rather than an opening to new futures. But the film does this brilliantly, thrillingly and both Carlos Diehz and Ralph Fiennes ensure this with their very different styles of actorly bring invisible interior truths (which aren’t all spiritual truths) to light.

Meetings within the conclave are supposedly open ones to its members, but the point the film constantly makes is that important decisions are never made thus openly, even in a closed community. The meeting of cardinals together are often suffused with a chiaroscuro of appalled dark and light with painful scenes painted on the walls but the men silent and self-enclosed.

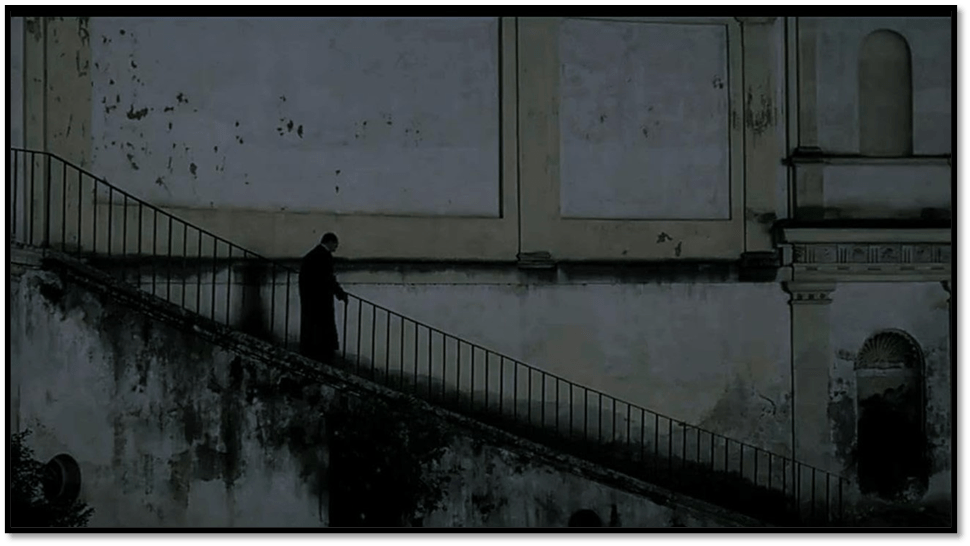

Lawrence himself uses the closure of conversations in transit to request, tell and hear secrets he keeps from others, such as in the scenes with the cleric who executes his commands, below on what feels like the most open of staircases but in fact communicating or seeking information kept in the dark.

People often ask for conversations in private in the film but often privacy is not in a room but a very open space, such as in this beautiful shot of communion between Lawrence and Bellini, using an open conclave in which basically, though neither of them(both basically good men in as much as masculinity can be good in this film) would call it that, to ‘plot’.

And closedness can be in the eyes, In a room where The last judgement peers down on you, the cardinals vote but their vote is locked in reasons kept behind a deliberately obscuring visage, that tells od secrets but not of what secrets. This close up of Fiennes as he casts his vote is a fine one.

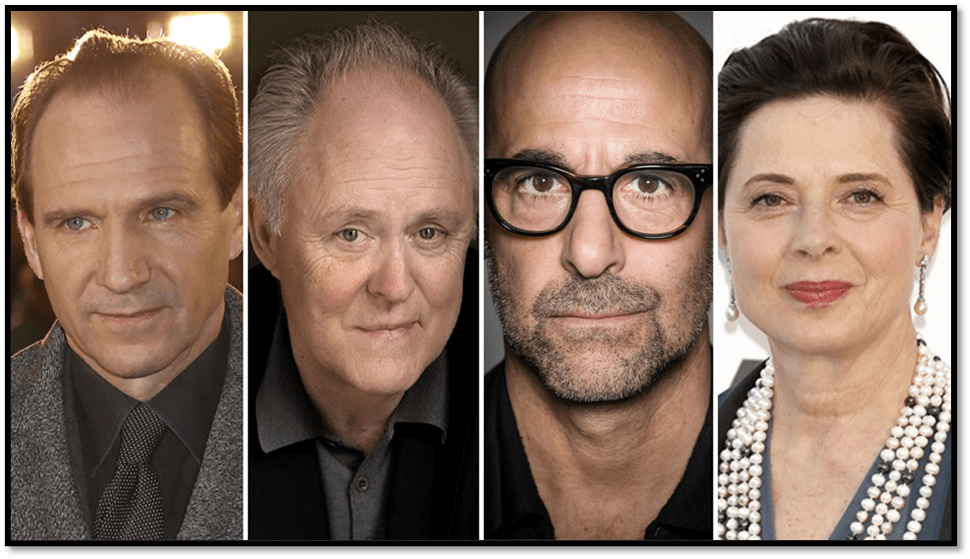

This is a film in which the great and the good perform with the precision of acting required, and I can end with the main publicity shot in the IMDB website, though it excludes those actors, whose difference is the reason for their appearance in the story and that is a pity. But great acting must be honoured too, mustn’t it?

Do watch Conclave. Do rejoice at the queer positivity of its ending.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx