We read about the weather all of the time and without thinking about them. I opened my smartphone cover, and the message hit me that ‘snow was likely to continue’ in my area of residence on the sides of the Northern Pennines in County Durham. Perhaps it caught my eye because I was concerned about friends taking a flight from Newcastle. But other associations soon grew, and my mind began ruminating on a phrase from the most famous of James Joyce’s short stories, The Dead: ‘Snow was general all over Ireland’.

Of course, I had to turn to the passage, but not before remembering that it emerged supposedly from the memory of the man who performs in the story the role of its main narrative point of view. Prompted by the sound of snow on the window pane, he remembers a journey to the west of Ireland he is about to make across the central plains from the eastern seaboard city, Dublin, in which he now sits and reflects, and with that he remembers a sentence from the daily weather reports in the papers. He just restated the phrase. I bold it below. But as then phrase came into my head, it came with puzzles entirely about the awkwardness of the word ‘general’ in it.

We are meant to understand that ‘all over’ the land of Ireland, the weather conditions are the same or can be generalised as the same. Hence, what follows in Joyce’s passage is a selection of reflections on parts of Ireland of increasing specificity until it rests on a vision of snow affecting the grave of Michael Furey, a man of whose fate as a rejected lover he has just heard, and who once tried to catch the attention of his beloved at her window from the ground below it. The ‘light taps upon the pane’ of the Dublin window by which he stands suddenly become as poignant as those Earnsjaw hears at a cold window pane in the opening of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, again from a ghostly lover who feels rejected

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

James Joyce in ‘The Dead’ in The Dubliners

The issue that struck me is that having read the term ‘general’ in the context of a series of weather reports, the narrator falls into a reverie about how and why the experience of snow might be one that is ‘general’ rather than specific. Of course, its obvious reference is to the fact of Irish geography and topography, but these spaces are clearly alsohtdmporal ones. The narrator begins to generalise snow, not by what it is but what it does, which is ‘fall’, and it is the manner of how snow ‘falls’ to the eyes of a viewer that becomes the focus of the prose.

Outside the window, it is ‘falling obliquely’ but only seen as such as it falls against a background of ‘lamplight’. To fall obliquely is to fall at a slant, but the term also has semantic relation to the notion of indirect expression and hence of hidden meaning, just as snowflakes being perceived as ‘dark’ gives them an association with the hidden or oblique, as in seeing ‘through a glass darkly’ in the King James version of St. Paul’s 1Corinthians 13, having unexpressed and indirect meaning potential to it.

And refernces to ‘falling’ act both obliquely and darkly thence forward in the passage, underlined by inverse repetitions, where phrases contain ‘falling’ as a verb are repeated but with their adverbial descriptor reversed, thus: ‘falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves’; ‘as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling‘. The effect, as in poetry is to emphasise that the meaning of falling is being generalised, made more general, than it’s primary significant ion of the fall of snow. And the answer is in the liturgical or ritual feeling of the prose at the end of the passage:

His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

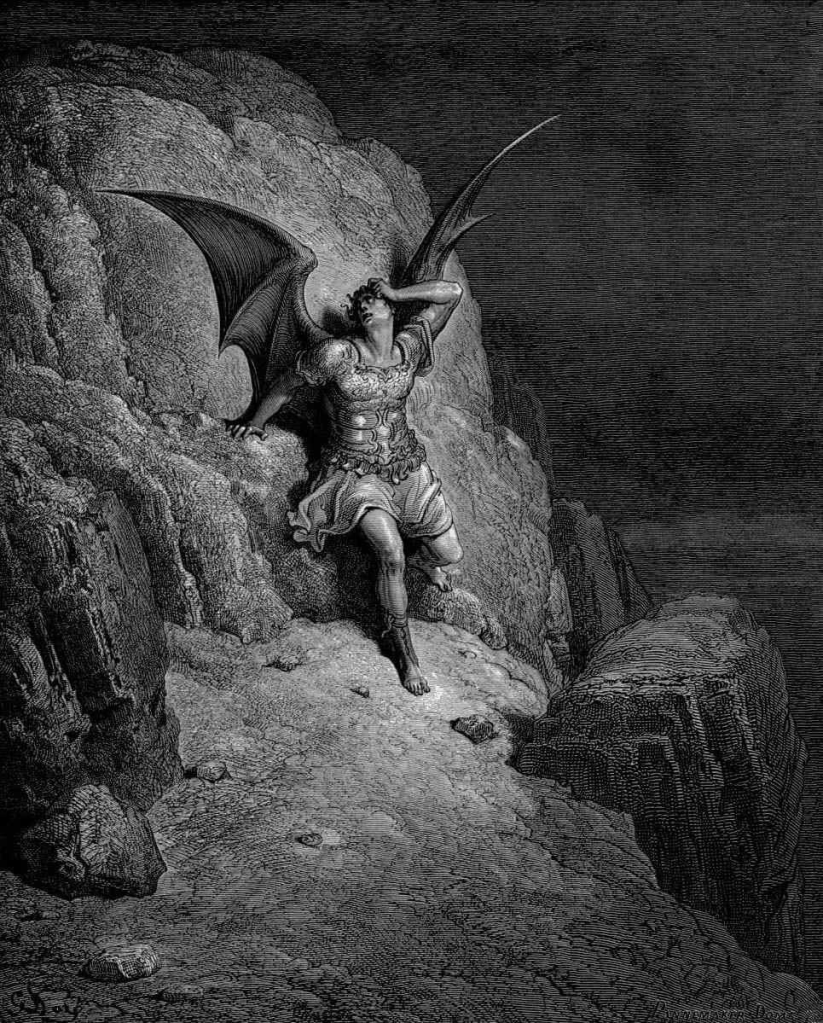

Souls once evoked can’t but queer the relationship of life and death as categories and come between them. When I swoon, I, as it were, experience a slight fall into a real pit or that more severe one called romantic love, but in liturgy and mythology, the fall of souls is a weighty matter, so much so that the greatest epic poem in English, Paradise Lost, is all about precisely that and the shock it imposes.

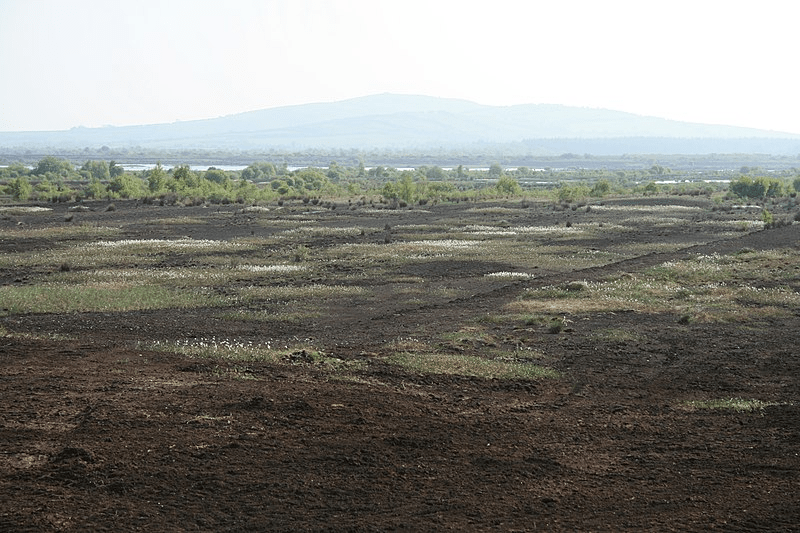

But the fall of the narrator’s soul, into a swoon at first, is not exactly that of a soul defeated but resisting defeat, like Milton’s Satan, but of one describing some final descent or fall that may or not be like the descent into the grave for a ‘last end’ , which is how the fall of snow is eventually described’ could be a purpose, an ‘end’ aimed at after falling ‘through the universe’, as well as a termination: ‘ like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead’. For if death is an end for a living, it can not be so described for those already dead, like Michael Furey. Likewise a ‘descent’ is not necessarily the same as a ‘fall’, a descent is the process of ancestry for instane, like that deforested ‘the treeless hills’ and created the bogs in which Irish ancient history was therefrom recovered, ‘the Bog of Allen‘.

Bog of Allen – Croghan Hill, Offaly, in the distance- self made by Sarah777

The point of the passage is to evoke, lyrically I would say, not why ‘snow’ is a generalisation of Irish weather but how the feel of ‘falling’ and ‘descent’, without which snow could not be snow, is generally the meaning of humanity, that which is lost to death and other obscurities evoked by the forgotten in the past but that supposedly that still lives, but whose life has descended into the trivialities of a bourgeois gathering in Dublin. As I wrote this I remembered that this very same phrase is worried to death in John Banville’s mystery novel, Snow (see my blog at this link).

But why does this matter? My point is that some sentences demand that you search their meaning despite their very obviousness. Did, now I have written this, I find that the ‘Snow’ that was ‘likely to continue’ do so? I ask myself: ‘Continue to do what?’ Certainly if its fall continued, it did so by metamorphosing variously into sleet and rain and back again. Did snow, if it did not continue to ‘fall’, continue to ‘lie’ on the ground and trees. It did but in a vanishing kind of way.

There is nothing ‘general’ about snow, but about the search for the ‘general’, there is something upon which we can always generalise.

Bye now

All my love

Steven xxxxxxx

One thought on “‘Snow was general all over Ireland’. Phrases that suddenly make demands on you that you understand them more fully.”