A good blogger has I feel already stolen my thunder in respect of the term ‘nothing’ in Shakespeare about which I had intended to blog about; having nothing other on my mind. That blog takes its evidence from a piece in The Daily Telegraph about the polysemous use of the tern ‘nothing’, pronounced ‘noting’ in Elizabethan Emgland in the play Much Ad About Nothing:

The familiarity of the phrase ‘much ado about nothing’ belies its complexity. In Shakespeare’s day ‘nothing’ was pronounced the same as ‘noting’, and the play contains numerous punning references to ‘noting’, both in the sense of observation and in the sense of ‘notes’ or messages. A third meaning of ‘noting’ – musical notation – is also played upon (eg in Balthazar’s speech ‘Note this before my notes/There’s not a note of mine that’s worth the noting.’) However it is a fourth use of the homonym – this time as ‘nothing’ – that is the most controversial element of the title. ‘Nothing’ was Elizabethan slang for the vagina (a vacancy, ‘no-thing’ or ‘O thing’). (1)

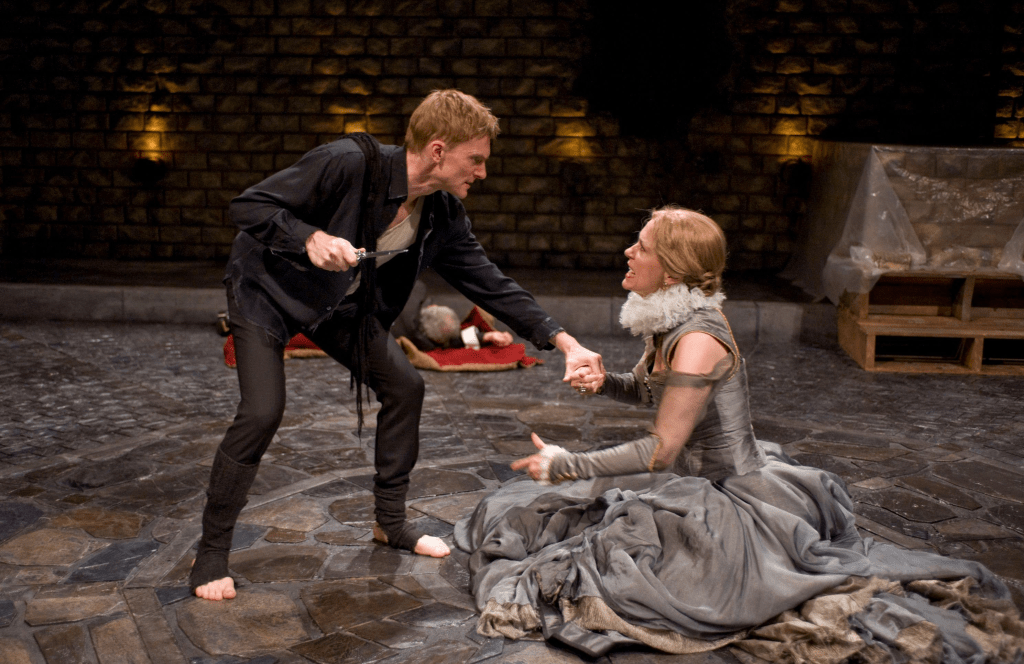

However, it also uses a note on an internet site which references these lines from Act 3, Scene 2 Hamlet that use the word ‘nothing’ with a constant play on matters of female sexuality where the homophone between the term ‘cunt’ and ‘country’ is mentioned alongside the pun which means that Hamlet jokes with Ophelia – in the presence of her father and the court before the entry of King Claudius and Queen Gertrude, his mother, that her ‘vagina’ is ‘a fair thought to ‘lie between maids’ legs’ :

HAMLET Lady, shall I lie in your lap?

OPHELIA No, my lord.

HAMLET I mean, my head upon your lap?

OPHELIA Ay, my lord.

HAMLET Do you think I meant country matters?

OPHELIA I think nothing, my lord.

HAMLET That’s a fair thought to lie between maids’

legs.

OPHELIA What is, my lord?

HAMLET Nothing.

OPHELIA You are merry, my lord.

HAMLET Who, I?

That Ophelia sees merriness here is interesting for there is no doubt that she is aware that Hamlet puns on her sexual parts in order to compromise her publicly, for he directly accuses her of sexualising his innocent behaviour: ‘Do you think I meant country matter?’

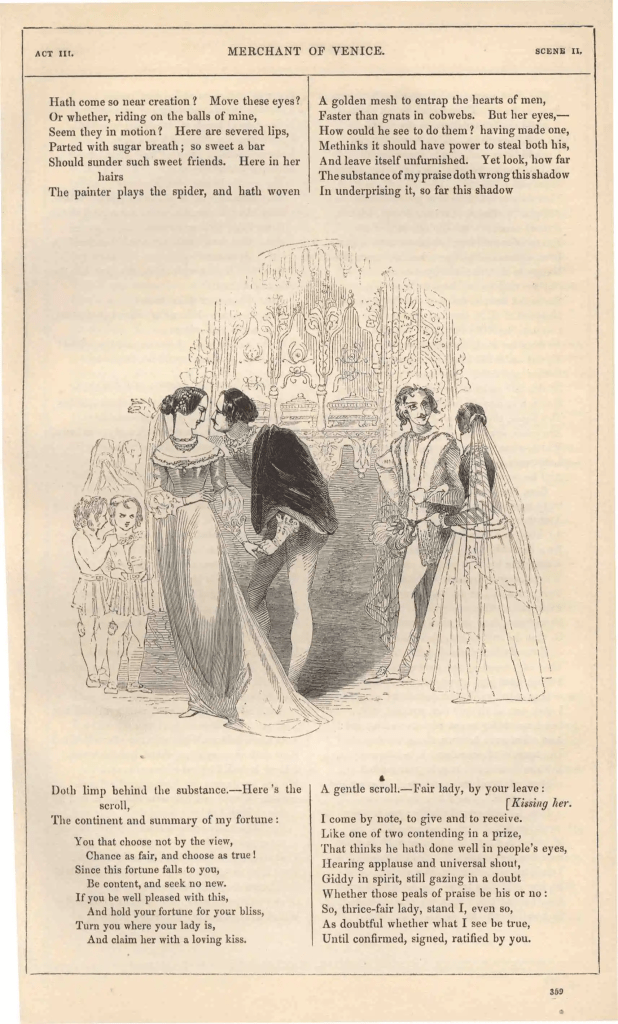

The comments on the blog show much amazement at the revelation of Shakespeare’s ability to make sexual punning a matter of even court behaviour – behaviour supposedly at its most socially and culturally refined. We might expect that of the characters of the underclass, like Mistress Overdone and Pompey Bum in Measure for Measure, but not of a royal court. Nevertheless we would be wrong. Sometimes the use of such punning is grotesque as in The Merchant of Venice Act 5, Scene 1. In this scene, Portia and Nerrisa, having returned from their cross-dressing jaunt where they outwitted Shylock while enacting the role of a legally educated lawyer (hence ‘Doctor’) and his clerk respectively. In that guise the women thought to be men had persuaded Bassanio and Gratiano to give up rings given to them by their affianced ladies, those same women. The scene ends with this from Gratiano:

Let it be so. The first inter’gatory

That my Nerissa shall be sworn on is

Whether till the next night she had rather stay

Or go to bed now, being two hours to day. (325)

But were the day come, I should wish it dark

Till I were couching with the doctor’s clerk.

Well, while I live, I’ll fear no other thing

So sore as keeping safe Nerissa’s ring.

Shakespeare’s play with transexuality is always urgent and considered. His thought of being ‘couched’ with ‘doctor’s clerk’ is playful but the play and humour is based on the the very mystery of why a male Doctor and his male clerk might have sought such obvious love tokens from the men in the first place. The whole virtue of determining that ‘nothing’ is a term for the vagina is entirely based on the fact that a ‘thing’ was initially a term for the penis, just as the term ‘ring’ could be the term for a sexual orifice -in tne end line for Nerrissa’s vagina. So what is Gratiano meant to say in his wish for a union with the ‘doctor’s clerk’ at a time when things are ‘dark’ and objects indistinguishable. Gratiano determines to ‘fear no other thing’ (another penis perhaps like that supposed on the supposed doctor) but his fear is expressed as a gradation of physical symptom (of soreness). It is possible this refers to the consequence of sexual bisexual or pansexual profligacy being a sexual disease, Yet the aim of stating his fear is ‘keeping safe Nerissa’s ring – an oath that he knows his own and her behaviour require gidance bebased on the fear of other things – other penises, but in relation to which of the couple (male or female remains unspoken). If Gratiano must rightly fear other men exposing their ‘thing’ to his wife, he must also fear other men exposing the same thing to himself. We are not a million miles away from the play on prick in Sonnet XX.

A woman's face with nature's own hand painted,

Hast thou, the master mistress of my passion;

A woman's gentle heart, but not acquainted

With shifting change, as is false women's fashion:

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling,

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth;

A man in hue all hues in his controlling,

Which steals men's eyes and women's souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created;

Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she prick'd thee out for women's pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love's use their treasure.

The pleasure of this sonnet is entirely bisexual, and imaginatively transexual in its pleasures. Having a prick does not stop Shakespear’s fair youth from passing as a woman or from performing in some limited sort a woman’s role. Yet at the sonnet’s heart is that pun on the vagina: ‘By adding one thing to my purpose nothing’. But try and parse that line and you end in contradiction. What the young fair youth has added is at first a ‘thing’ and then a ‘prick’ but it is, by being added ‘to my purpose nothing’. What does he mean? At one level, he says – since you have a thing I cannot use mine on you, but could the thing added actually be ‘nothing’? A sexual orifice not guarded and blocked by anything. Shakespeare was capable of such ambiguities.

Do we have to prick up our ears then every time the term ‘nothing’ is used by the Bard? Take my recent blog where I cite the words of eunuch, Mardian – a man with a compromised thing – who says when asked if he has ‘affections indeed’ says:

Cleopatra. ... Hast thou affections?

Mardian. Yes, gracious madam.

Cleopatra. Indeed!

Mardian. Not in deed, madam; for I can do nothing

But what indeed is honest to be done: (540)

Yet have I fierce affections, and think

What Venus did with Mars.

To ‘do nothing’ is not a clear sexual ambiguity but it references it and when paired with the imagination of ‘What Venus did with Mars’ raises the spectre of a substitutive vagina, even if only in the mind) that is not the absence of a ‘thing’ but an active principle itself – able to ‘do’ to Mars things that enact ‘fierce affections’.

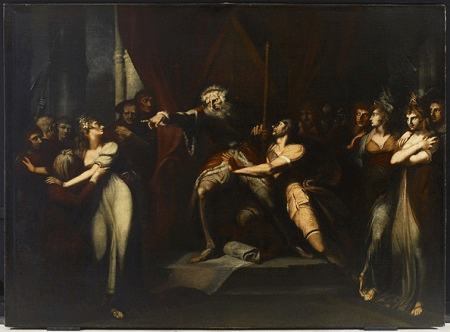

So in that case I think the pun has force. But what of King Lear. That vain King asks of his daughters ‘Which of you shall we say doth love us most’ (Act 1, Scene 1, line 54). The daughters Goneril and Regan both pour out words of fealty and love to their father but Cordelia responds that when asked this question she can only say ‘Nothing’. To which Lear responds: ‘Nothing will come of nothing. Speak again’. There seems no room for pun here based on sex / gender. But do not be so sure. When comparing her sparse words, equivalent to ‘nothing’, Cordelia says:

Good my lord,

You have begot me, bred me, loved me.

I return those duties back as are right fit:

Obey you, love you, and most honor you.

Why have my sisters husbands if they say

They love you all? Haply, when I shall wed,

That lord whose hand must take my plight shall carry

Half my love with him, half my care and duty.

Sure I shall never marry like my sisters,

To love my father all.

It has always struck me that this most wonderful of plays constantly references sexual generation and attributes duties in relation to roles in sexual generation. Her decision not to overpraise her father is a decision based on her ‘care and duty’ to a yet-undecided husband, and blames her sisters for neglecting their ‘care and duty’ to theirs. That this fealty to ones role as lover of a husband and including being the bearer of his children (patrimonial descent is never questioned in this play) is the equivalent of the female duty based on having nothing until gifted it by a man.It is not long before Lear renounces his paternity of Cordelia and denies his role in her generation, even ‘those orbs by which we do exist’, his gonads I think:

.. .Thy truth, then, be thy dower,

For by the sacred radiance of the sun,

The mysteries of Hecate and the night,

By all the operation of the orbs

From whom we do exist and cease to be,

Here I disclaim all my paternal care,

Propinquity, and property of blood,

And as a stranger to my heart and me

Hold thee from this forever. The barbarous Scythian,

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite, shall to my bosom

Be as well neighbored, pitied, and relieved

As thou my sometime daughter.

Driven to madness, those same gonads will spill all the bounty meant to come from man (in Act 3 Scene 2 cited below) and leave only the principle of active generation that can only be proven, other than in the word of law, by women.

Blow winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow!

You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout

Till you have drenched our steeples, ⟨drowned⟩ the cocks.

You sulph’rous and thought-executing fires,

Vaunt-couriers of oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head. And thou, all-shaking thunder,

Strike flat the thick rotundity o’ th’ world.

Crack nature’s molds, all germens spill at once

That makes ingrateful man.

Every principle that man inserts into the pregnancy of women is disclaimed here as disordered and sperm (germens) spill everywhere irrationally. Cordelia may have ‘Nothing’ to offer – but nothing (the absence of the male organ) is a better basis of justice than its presence. So don’t be too sure that Shakespeare does not use puns based on sex / gender even when he is operating at his most metaphysically profound – whether he uses it consciously or not, I can’t decide.

With all my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

_______________________________________________________________

(1) From The Daily Telegraph – behind pay wall at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/booknews/8313901/Title-Deed-How-the-Book-Got-its-Name.html

One thought on “When sexual innuendo is intended and when it is not in Shakespeare’s plays: ‘Nothing will come of nothing’.”