Will there ever be a vocabulary that describes adequately the vengeful annihilation of a whole people? This is the more poignant in that this is a people that is already displaced and sequestered by international agreement and deprived of the definition and identity held by other recognised nation-states. Palestine 🇵🇸 is a nation whose very existence has been denied expression and whose grim fate is to be the spectacle of an atrocity in action denied even recognition for being what it is, a killing of a people and its culture: genocide.

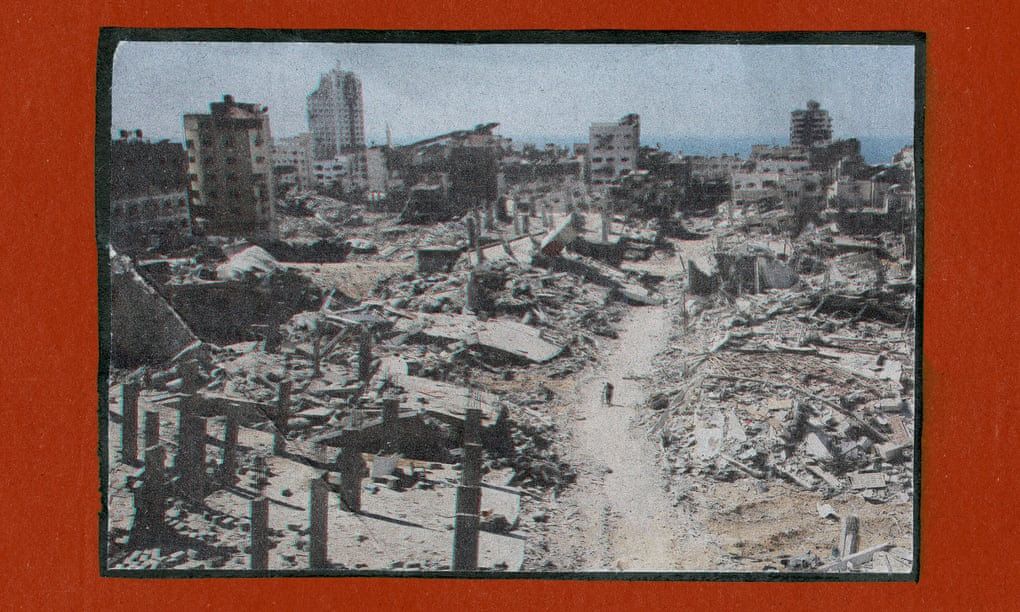

One of the most upsetting articles ever to be published, in my opinion, is one by Alice Speri in The Guardian on 20th December 2024, accompanying the photograph below in which a person is perceptible walking through the ruins of Gaza. It is not an article about the extermination of Gaza and Gazans but about a debate within the US academic world about how to describe that extermination and to determine its context as a world event. [1] Speri writes, citing Raz Segal, a US based Israeli historian, who has been excluded from the community of Holocaust studies historians for calling the events in Gaza a ‘genocide’

This seems to be an approach to the subject that is as cruel as the events they seek to describe. It is a debate about an academic subject, ‘genocide studies’ and its permitted parameters of inclusion and exclusion. The problem of definition lies in the very origin of the subject from within the study of a specific and horrifying ‘genocide’ the Holocaust of European Jews. Speri writes:

The field of Holocaust and genocide studies originated in the aftermath of the genocide of the Jews during the second world war. It expanded in the 1990s in response to more instances of mass violence, including the Bosnian and Rwandan genocides. That expansion was controversial for some, and the disagreement continues to play out.

“The idea that the Holocaust is unique, and Jews are unique, and Israel is unique, the exceptional status of Israel, is foundational to Holocaust and genocide studies,” said Segal, …

The kind of exceptionalism described by Segal is hard to reconcile with the idea of academic rigour about evidence. Some witnesses reduce it to a case of the heightened fear of appearing to be antisemitic or of minimising the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps, appearing therefore to lose all rigor in front of a stereotype of the Israeli nation. Speri shows that, even amongst historians meant to honour truth, that it “is very difficult to accept that a nation of victims could in itself commit genocide”. Said like that one would almost imagine that ethnic cleansing were not a common theme in the histories of all peoples who considered themselves ‘chosen peoples’ as in phases of the history of Rwanda and Bosnia where ‘genocidal acts’ occurred.

But the odd thing about the academic debate in the USA is its distance from realities, even those of history and the application of ideology, of all kinds. The academics behaved as if the debate about real and widespread mass deaths in Gaza were really “like a high school fight”, according to ‘Uğur Ümit Üngör, a Dutch Turkish historian based in the Netherlands’ cited in Speri’s article. Historians refused to sit next to or talk to each other and shouted out slogans at each other. The animosities can run deep and cost academics glittering prizes. Lev Bartov, who with Segal, has done most to raise the protest against Israeli, did that at the coast of a prestigious academic appointment. But he makes it clear that this is not just about a word. The point is that you can deny genocide for all kinds of reasons, such as lack of overt and stated intent, and still recognise, in his words that ‘“There’s been systematic destruction of everything that makes it possible for a group to survive as a group, and so the result can be seen as an attempt to destroy the Palestinian people,….” . Üngör articulated the question at the heart of the debate in an email she sent her mentor in the subject early in the war: “Do you only study genocide or do you also want to prevent it?” And hence my title from ‘Hirsch, the scholar of memory’:

“Genocide prevention is a responsibility,” she said, citing Philip Gourevitch’s well known book about the Rwandan genocide, We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families. The book’s title implicitly calls out those watching as a genocide unfolds. “Now, we’re watching on our iPhones, and still people are holding back.”

Speri’s article will soon be forgotten but less soon than seems to be the atrocities in Palestine that people seem able to just watch unfold. The fear of being called ‘antisemitic’ has been pushed so far by mindless celebrities like Rachel Rilet and David Baddiel that the only thing that matters now is a willingness to see Zionism as a mere defence of borders rather than an act of appropriation and settle colonialism run so wild, it engages in pre-emptive strikes on a Syria freed from a Fascist monster. We have as a result lost all credibility that anyone wants a two-party state in the Palestinian dominion. Israel is a nuclear state. This should strike terror in all of us.

____________________

[1] Alice Speri The Guardian on 20th December 2024. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/dec/20/genocide-definition-mass-violence-scholars-gaza