The ethical ideal is not to tamper with living things but does that extend to living tissue used in experimental study of brain connections? The example of laboratory cultured models of brain systems from living tissue in the laboratory in order to test what the variables are that might affect mental processes, as we think they are represented in these systems, and to manipulate those variables.

By changing the size and shape of the tiny tunnels (called microchannels) that connect the neurons, the team controlled how strongly the neurons interacted. Credit: Neuroscience News

A new manner of studying the brain has been used for a long time in neuroscience that gets far less publicity than the research on the brain using computer networking or ‘connectionist’ (links to difficult website) models. It does work like connectionism (links to Wikipedia -a better start) in some ways in that it creates hypothetical models of how the brain works but works directly with living neurons as its materials. An early article of 2019 sets the period of the work over a long period of time: ‘Over the past century, robust methods were developed that enable the isolation, culture, and dynamic observation of mammalian neuronal networks in vitro’.

In this article, Keller and Frega, advance a case for the legitimacy of these models whilst admitting they do not replicate real brains per se ‘when it comes to studying either the healthy or diseased human brain’. What they study is what connectionist and other artificial intelligence models studied before, and largely, they replicate their results rather than advancing knowledge. What this study contributes, as an example, is to ‘a collective drive in the field of neuroscience to better understand the development, organization, and emergent properties of neuronal networks’.

Largely the studies I have seen, as an amateur so not to be taken as a valid judgment, seem to support hypotheses about the emergent quality of brains we call memory registration, consolidation and recall. However, I think the deliberate abstract statement here is to posit that we might, in some distant future, take a pot at understanding the most complex of the emergent qualities of neuronal systems; consciousness. But the abstract to this article so words its argument that it is difficult not to see a longing eventually to work on a living system that in the long-awaited future fills the present deficits of in vitro cultures of brain processes by replicating them all in a way indistinguishable from a living brain: ‘But even if neuronal culture cannot yet fully recapitulate the normal brain, the knowledge that has been acquired from these surrogate in vitro models is invaluable’ [my emphasis].[1]

Though I taught foundation level neuroscience for the Open University, work on these experimental models was not mentioned in the textbook (dated 2010), or if it was I failed to notice it, though I read it many times. My introduction to it was then from an article this year in Neuroscience News

The article boasts a discovery as new (that it is I cannot verify) that these models have created a sound basis for the concept of neuroplasticity, a key concept in debating the nature-nurture or biology-social construction debate. Neuroscience News is not an ‘academic’ publication as such and is more engaged in creating summaries for the non-specialist interest in neuroscience than full papers. Yet, the summary is provided by the university representing the writer of the original paper. It summarises the key facts learned thus:

- Key Facts

- Realistic Networks: Microfluidic devices enabled neurons to form natural-like brain networks.

- Neural Plasticity: Repeated stimulation altered neuronal ensembles, mimicking learning processes.

- Advanced Models: This technology can be used to study memory formation and brain function.[2]

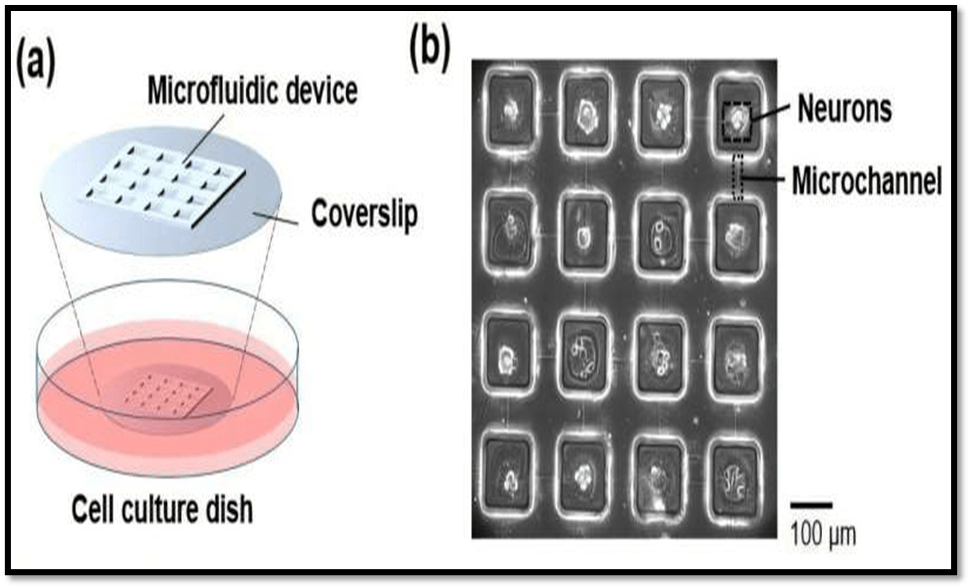

I think a novice (more so than myself who truly am one too) in neuroscience might be rather surprised by the term ‘realistic networks’ if they were to see a graphic of the physical model in which the neurons were cultured and manipulated, feeling carried away by the artistic representation of a neuron in Neuroscience News. The readers of the summary in Medical Xpress got more of a flavour of the controlled methodology of the model of brain processes, with this graphic, which looks more like a circuit board, that might be used in AI, than a ‘realistic brain’. But of course, the term ‘realistic applies to the reproduction of the process, not the appearance of the model:

(a) Schematic of the microfluidic device and cell culture. (b) Photograph of neuronal networks. Neurons are separated by square areas, and these are connected through the microchannels. Credit: Adapted from ‘Advanced Materials Technologies’ (2024). DOI: 10.1002/admt.202400894

Having seen this graphic, the summary in Neuroscience News is more readable:

Summary: Researchers have developed lab-grown neurons that behave more like real brain networks, advancing the study of learning and memory. Using microfluidic devices, the neurons formed diverse and functional networks, resembling those seen in living nervous systems.

These networks exhibited complex activity patterns and showed neural plasticity, reconfiguring in response to repetitive stimulation. This breakthrough provides scientists with a powerful new tool to study brain functions under controlled lab conditions.

The key term to understand the term ‘realistic’ is ‘controlled conditions’. For it is this need that allows us to understand that the ‘model’ of the brain process – even using real stem cell neutrons – has to be so simplified to be artificial. It has to be so that its independent variable components can be manipulated and a dependent variable isolated that can show the effect of the manipulation of the independent variables (remember those experiment research sessions, chums)!

There are two effects of the need for control. It means that experiments lack ecological validity – they are not like the phenomenon they are studying in the real world context, where more free variables abound. Controlling these is one of the causes of cruelty in animal model experiments like Pavlov’s and Skinner’s. But it also means that the variables tested are so outside the environment of the phenomenon studied that they are extremely artificial and therefore both invalid and have the potential for little or no reliability in the measurement of effect on the dependent variable.

Tohoku University actually say about work on in-vitro cultured metworks prior to their experiment that, and in this statement statement there is nothing new:

“Neurons that fire together, wire together” describes the neural plasticity seen in human brains, but neurons grown in a dish don’t seem to follow these rules. Neurons that are cultured in-vitro form random and meaningless networks that all fire together. They don’t accurately represent how a real brain would learn, so we can only draw limited conclusions from studying it.

What they claim is that they have manipulated the in-vitro model to ape learning by association, though in doing so they make assumptions that come from connectionism about the relative strength of links between neurons.

They showed that such networks exhibit complex activity patterns that were able to be “reconfigured” by repetitive stimulation. This remarkable finding provides new tools for studying learning and memory./

…

In certain areas of the brain, information is encoded and stored as “neuronal ensembles,” or groups of neurons that fire together. Ensembles change based on input signals from the environment, which is considered to be the neural basis of how we learn and remember things. However, studying these processes using animal models is difficult because of its complex structure.

…/../

The research team created a special model using a microfluidic device–a small chip with tiny 3D structures. This device allowed neurons to connect and form networks similar to those in the animals’ nervous system. By changing the size and shape of the tiny tunnels (called microchannels) that connect the neurons, the team controlled how strongly the neurons interacted.

The researchers demonstrated that networks with smaller microchannels can maintain diverse neuronal ensembles. For example, the in-vitro neurons grown in traditional devices tended to only exhibit a single ensemble, while those grown with the smaller microchannels showed up to six ensembles.

Additionally, the team found that repeated stimulation modulates these ensembles, showing a process resembling neural plasticity, as if the cells were being reconfigured.

The conclusion reached has huge potential. It is the plasticity involved in re-configuring links in the brain that can be used to show how early trauma creates complex unshakable memories but also how vastly accelerated learning that is beneficial can also occur. If adverse and beneficial learning change brain configuration then many problems in mental health and learning can be looked at again with confidence and support the role of interventions like teaching, counselling and the fallacy of supposed biological truths that have left so many in despair – people who use dangerous substances apparently involuntarily, those with ‘phobias’, or trauma-related stress of huge consequence to basic issues of trust and attachment.

But they also enable a more wholesome approach to notions of identity fluidities and plasticities and a rejection of the link in its steadfastnesses (who mentioned J.K. Rowling) of ‘biology’ and guilt at not meeting prescribed norms. Plasticity is at the root of individual and social diversities.

Are stem cells legitimare subjects for manipulation? Any more than bacteria? What does it mean to work on living tissue and in the long duration model a complete brain. Is this helpful science or the myth of Frankenstein? I would need more wisdom than I have to work these questions out!

Well, that’s me for today.

All my love, Steven

[1]Keller, J.M., Frega, M. (2019). Past, Present, and Future of Neuronal Models In Vitro. In: Chiappalone, M., Pasquale, V., Frega, M. (eds) In Vitro Neuronal Networks. Advances in Neurobiology, vol 22. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11135-9_1 Abstract cited here available at: https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/past-present-and-future-of-neuronal-models-in-vitro

[2] The original article is by: Hakuba Murota et al, Precision Microfluidic Control of Neuronal Ensembles in Cultured Cortical Networks, Advanced Materials Technologies (2024). DOI: 10.1002/admt.202400894 but I read it in Tohoku University’s contributions to digital magazine Medical Xpress (Tohoku University (2024) ‘Lab-grown neuronal networks better represent plasticity of the brain’ in https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-12-lab-grown-neuronal-networks-plasticity.html#:~:text=Neurons%20that%20are%20cultured%20in-vitro%20form%20random%20and,can%20only%20draw%20limited%20conclusions%20from%20studying%20them) and, of course, Neuroscience News (Tohoku University (2024) ‘Lab-Grown Neurons Mimic Brain Networks, Exhibit Neuroplasticity’ in Neuroscience News December 17, 2024 Available at: https://neurosciencenews.com/lab-neurons-neuroplasticity-28260/)