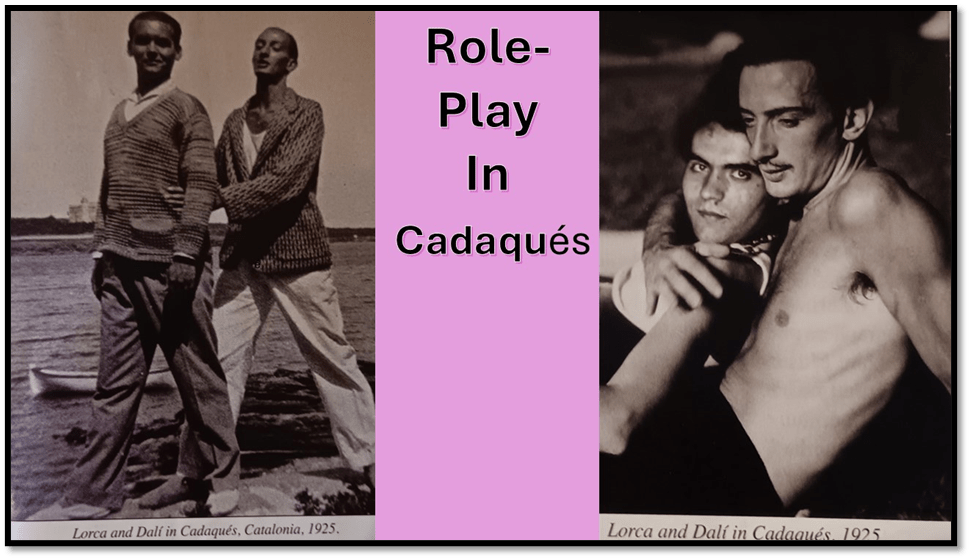

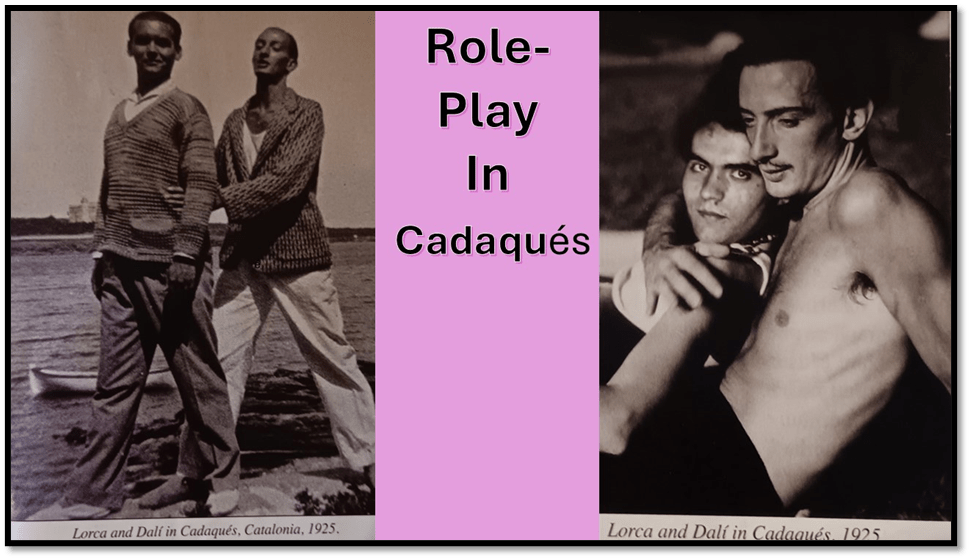

Though the photograph on the left in the collage above is nothing more than role play such as you might expect from two artists of the sublime camp side of art, the one on the right seems the very picture of genuine mutuality whether of lovers in fact (sexual or Platonic), or good friends. They both come, these photos, from the latest edition of Gay and Lesbian Review (November-December 2024). In that edition, there are two charming pieces on the love of the surrealist painter above, whom I can not find it in me to call great, and a very great surrealist poet and artist. As the latter, the poet, was much nearer to Joan Miro, as an artist at least, whom he admired enormously, than to the painter and enactor of Narcissus.

There are a few reasons Dalí gave for the inability to share their love, the most convincing being that though he believed that love ought to be sexual, a great claim from a man who prided himself on being ‘The Great Masturbator’, but that though ‘Lorca tried to have sex with me twice but I resisted because it hurt’. (1) Of course, we have to remember that he only tried sex with his wife Gaia once and did not like what he tried. Gaia was so jealous of Lorca she destroyed his letters to her husband. What seemed clear too here is that the painter resisted in a passive sexual role, a role he never wished to see himself in, just as Lorca too resisted the role of what he called the ‘pansy’, the passive queer male, and whom he lambasted in the name of an embrace of Whitman’s ‘comradely male love’ that was nevertheless sensually realised in the body. I have written about this in an earlier blog (at this link).

Another reason sometimes cited for the inability for these men to share love was that Dalí was unwilling to confront the homophobia of the great French surrealists. André Breton considered love between men an abomination, whilst Luis Buñuel waited, Darnaude tells us, outside queer clubs, in order to beat up the men who had anything to do with them. Of course, both Lorca and his beloved were hoist upon the pétard of heteronormativity, which proposed the great contradiction for them that particularly made any passive role in male-to-male sex ‘disgusting’ to them, unlike the male role.

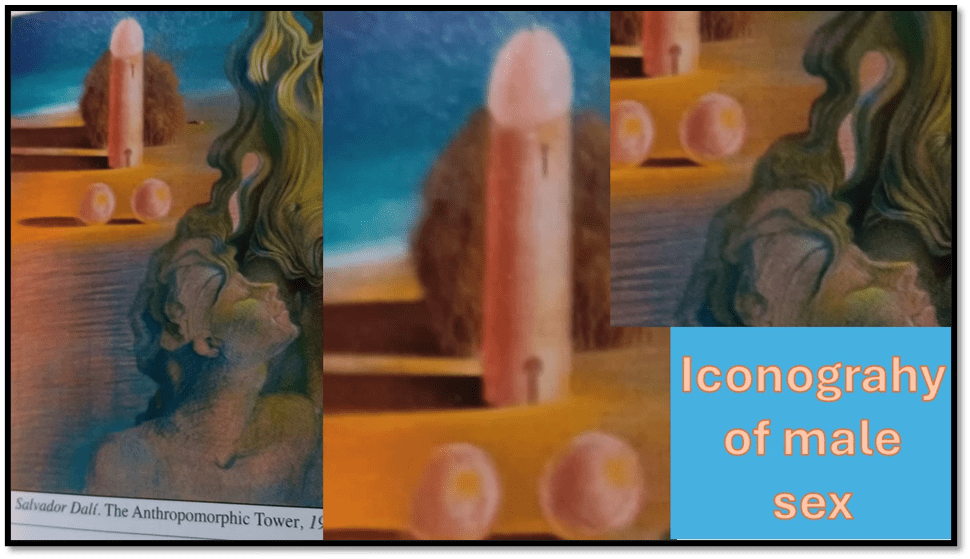

Whilst Dalí explored feminine male roles in his paintings the great puzzle to unlock (see the keyhole icons below) was for him, and all men he thought, the centrality of the ‘anthropomorphic tower’, the largely conceptual phallus that is situated in the highlight of desire in his painting. The androgynous male pictured below the phallic tower emits sperm from an imagined phallus, it’s bell alone visible, in his own headthat merges into the flow of his feminised hair, in which his arms are lost in orgasmic delirium. I do not like this painting (see it above from the reproduction in the cited article).

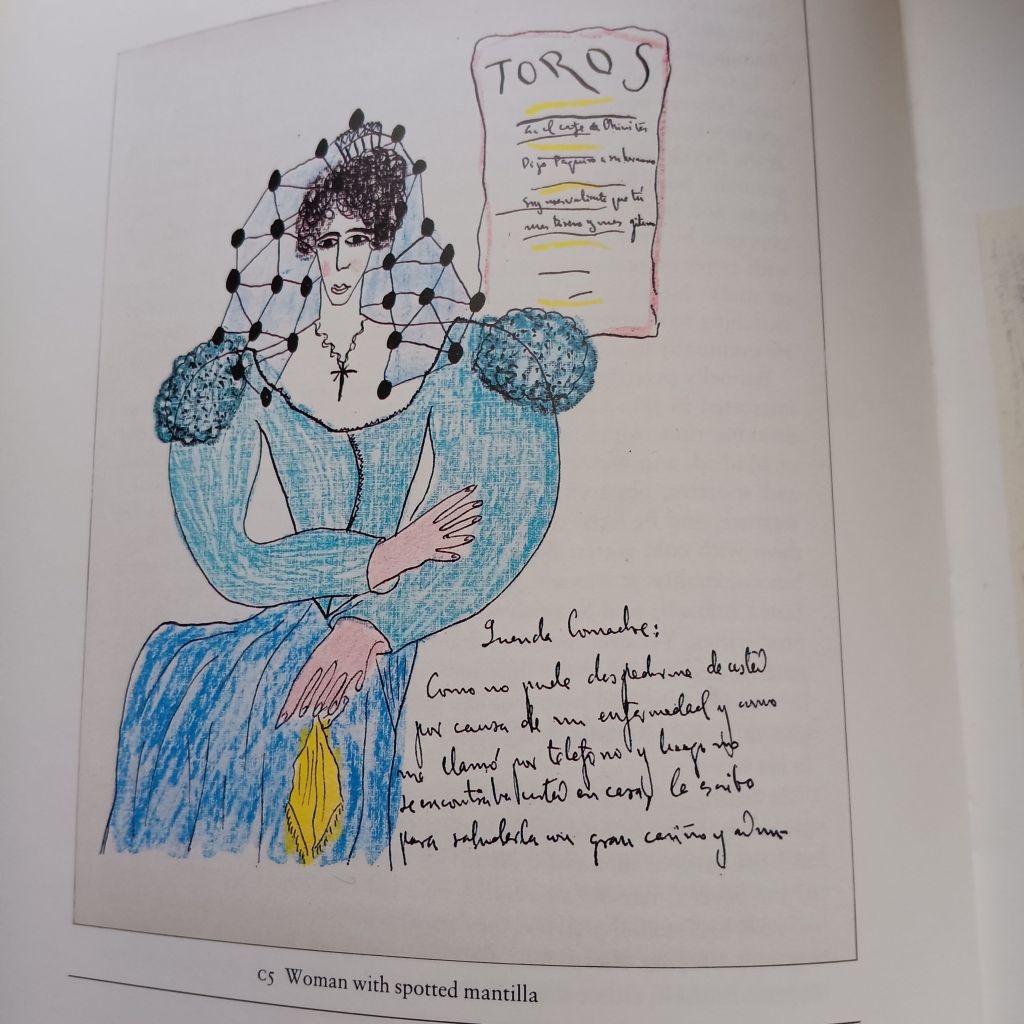

Lorca must have negotiated his issues with roles in male to male sex in Havana, where his sexual life bloomed and that could not have been done if everyone kept to the prescribed rile of the man of being the penetrator of another equally manly body only (for the man would be scripted in the ideology to resist penetration just as much,, even orally. As both Darnaude an Emily E. Quint Freeman show Lorca could explore the love of men for men by coded paradigms and particularly the in-habitation of female bodies by what the world recognised as ‘male’ souls because of the predominance of the coded binary of the meaning of sex in practice and ideological heteronormativity. Such women include Yerma and the Spinster Dona Rosita.

Implicating in those codes was the supposedly generally and widely encoded desire in women (and ‘pansies’) for men, monstrous in size and moral behaviour, notably bull fighters, though sometimes the bull himself (Toros).

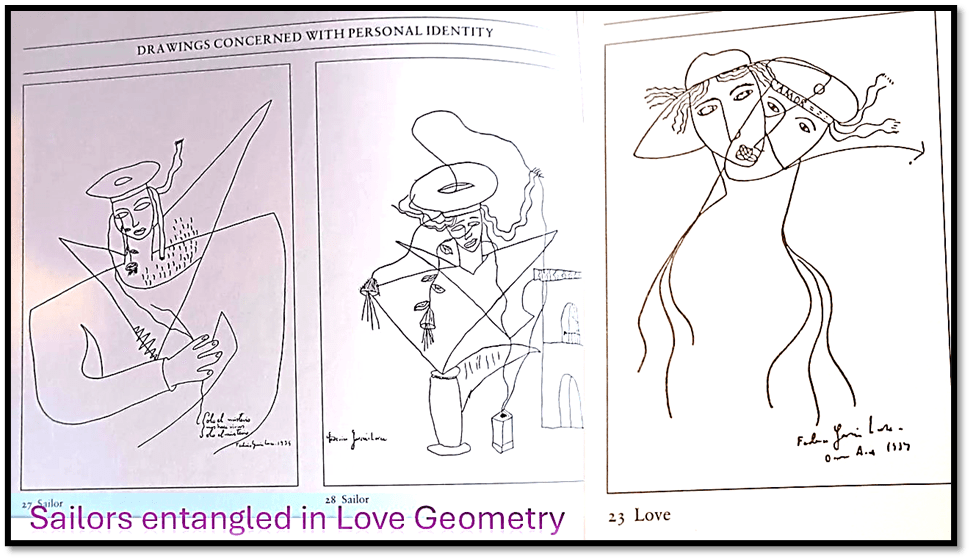

Picasso, too, used this paradigm, though he himself was often coded as the bull itself or Minotaur. Another fantasy resource for queer men was the queer paradigm of the man who crossed sexual and other boundaries, such as the gypsy in Lorca’s Gypsy Songs and the sailor in Lorca’s drawings.

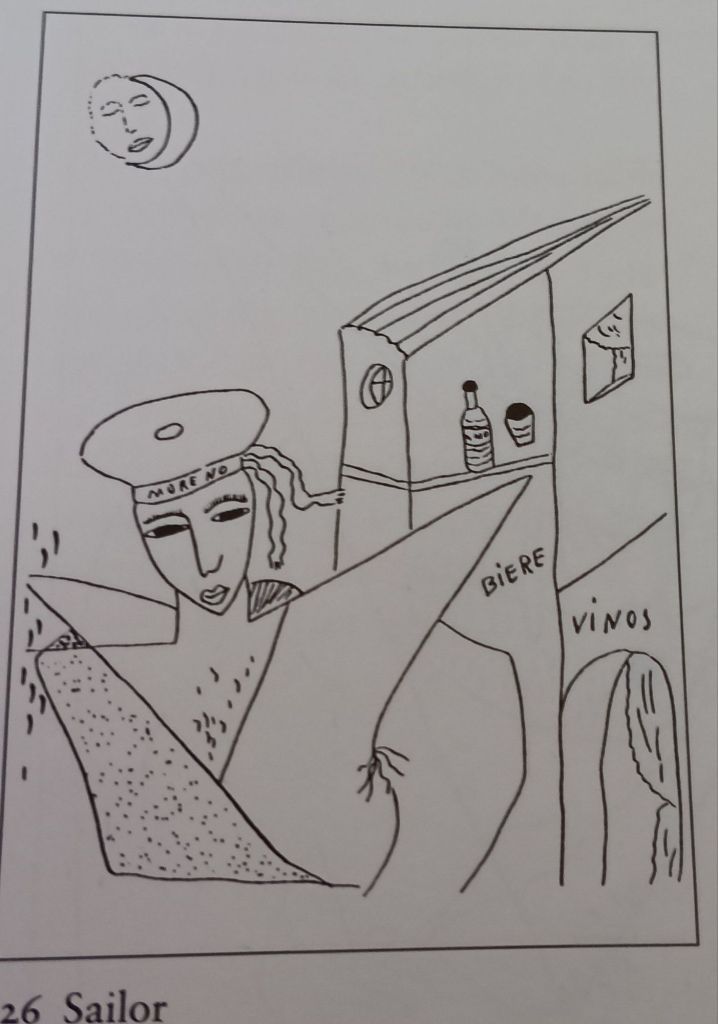

Pictures from Helen Oppenheimer (1986) ‘Lorca: The Drawings,’ London, The Herbert Press. A prized book in my collection.

The sailor could be coded as androgynous in sex and gender as in the drawing on the right in the collage above, where both heads are implicated in the androgyny of the drawn lines beneath them which suggest breasts. One head is entirely androgynous but it shares a mouth with the sailor, more typically iconograpphically male. This fantasy alemows the mouth one kisses or that is penretrated by the male phallus be both male and female simultaneously. It is a perfect resolution of the queer male dilemma of thirties European sexualities.

His lone sailors may be more clearly masculine (left and centre), but they have very fluid boundaries that constantly play games with the icon graphic representation of male and female, inside and outside and interpenetration of self and object boundaries. See, for instance, that hole through which a borderline is threaded. One such borderline leads to a bedroom window. Helen Oppenheimer sees this as typical of the fluidity of the representation of sailors by Lorca. She writes:

The sailor is another visual symbol through which Lorca explores the question of identity. Here again, as sith the severed hands, sexual freedom is identified with the notion of creative freedom. The sailor has much in common with tne gypsy in that they are both outside society and to a certain extent they both represent freedom and the natural life. … The word ‘love’ is often written on a drawing of a sailor, and sometimes there is an inviting bedroom in the background. (2)

In fact, the sailor , though as abstract a being as Oppenheimer says he is, is in Lorca conceptually rich associated with beer and wine as might be expected but also with books of poetry. They are ambiguously feminine at times, with huge shoulder blades and like the ‘old moon in tne new moon’sarms, in the picture below:

The marks that constitute the hairs on this sailor’s chest are not unlike and rhyme with the tears that fall beneath the moon.

Dalí died with the words ‘My friend Lorca’ passing his lips, though Lorca himself was now the victim of Fascist Spain as a known queer and socialist man. Lorca’s life cannot be seen as a queer tragedy as well as the political one it was. The only tragedy in his queer life was that knowledge of it was suppressed by his Patricia family after his death in order to, they claimed, ‘protect his reputation’.They even claimed, quite falsely, that his sexuality was ‘irrelevant’ to his art and a ‘morbid’ subject to discuss.[3]

As nearly always queerctragedies are less those of natural life than of imposed heteronormativity.

_________________

(1) Cited Ignacio Darnaude (2024: 16) ‘The Love Song of Lorca and Dalí’ in Gay and Lesbian Review (Nov.-Dec. 2024, XXXI, No.6.), 15 – 19.

(2) Helen Oppenheimer (1986: 53) ‘Lorca: The Drawings,’ London, The Herbert Press.

[3] Darnaude op.cit: 16

_______________________________________________________________________________