I had intended not to write up actually seeing Danez Smith, given that I have written up my response to his written poems (at least that is what is I say at the linked blog here), which I love. You can read these responses at the links: on the poem Sioux Falls, and on the volume Bluff on the whole. But a poet like Danez Smith is much more than printed text of his poems. Though some are poems to the eye they are rarer than you think, though many could not be read by voice alone (such as sonnet, pages 910-117), he himself thinks only rondo (pages 35 -41) can be said to be for the eye alone (but then I can’t imagine myself trying to read its sequential footnotes without voicing them). He explained how the broken black line across its pages rep[resented the motorway that cut up the Rondo black community by dividing its space and imposing on it a new time-scale of being knowable to its inhabitants. That was truly illuminating – it has an obviousness now I can’t believe I was capable of missing – but I was!.

This even was powered by voicing – not just the poet but the voicing of invited (and even formally uninvited but culturally embedded response points). Reading anti poetica (page 3) the audience audibly responds to each line with a voiced affirmative, as in the responses to a Gospel Church sermon, celebratory of the truths voiced by the preacher-poet-seer. the responses raised to a crescendo in the line:

there is no poem in the winter nor in whiteness

When I think about why I felt uneasy about writing about the event I wonder if the feeling touched on things I even dare not admit – like the feeling of white exclusion from Black cultural norms. Such feelings are after all clearly those of entitled category – white people – feeling a taste of the exclusion white people have without thinking cerated to guard their own events from Black participation, except on white cultural terms and using White cultural norms that White people themselves don’t see. In my second blog, I pointed out how in Smith’s Bluff , one manifestation of the bluff of white culture is the claim that it is open to all. When Smith read the lines from less hope (pages 16-170 about the compromises White audiences expect of him as a black poet if he is to win their ‘awards’ get from ‘checks’ to cash, such as editing:

... my war cries down to prayers, ... I sang for my enemy, who was my God.

There was an audible gasp of recognition at the communally recognized put-downs to Black culture from White voices, especially a cheer when he asks Satan to:

teach me to never bend again.

But why should White people,and me included,expect never to learn that feeling of exclusion, well earned in their cultural history and inherited forms of current day cultural boundary-making. At a later point Victoria Adukwei Bulley, interviewing Danez, spoke of how badly white critics take to the address to verbal violence in poems. They call them ‘raw’, Smith laughed: ‘meaning “get them edited!”‘. For Victoria this comes in part from a failure of the critics in a white hegemonic culture to understand Black humour and irony, but I wonder if that oversimplifies. For the unconscious bluffs of white culture were to some extent replicated in this event – in the performed closeness of the interviewed and interviewer, the selection from the audience of questions know to be friendly from members of it known personally as a writing colleagues to Victoria. But we don’t notice that usually in events where everyone speaks the hegemonic language of White artistic culture. That an awareness of mutual exclusions, where one is based on greater and wider power over the other, as a in White hegemonic culture, is sometimes mediated by the worst human emotions such as fear and suspicion is hardly surprising, and ought to be expected. To expect it not to exist is naive.

The Southbank venue is a kind of haven of anti-establishment culture parasitic on the mainstreams of European white culture. That goes for class too. I have never felt so working class and Northern in origin as sitting in the foyer of the building amid spectral columns within the building brutal architecture (se above) with mu bags and big coat and harassed lost look. Yes there are enclave archives of resistance, like a Palestinian music archive in the Queen Elizabeth Hall, but not a single member of the everyday staff at doors into the building or on the floor in that building knew it existed (it is on the left as you enter from the raised terrace facing the Thames, overlooking the Purcell Room.

The Purcell Room too has a kind of institutional grandeur, at its portal and then within in its raked institutional elegance.

Inside this is more conspicuous, at least in the fifteen minutes before the show began.

We waited.

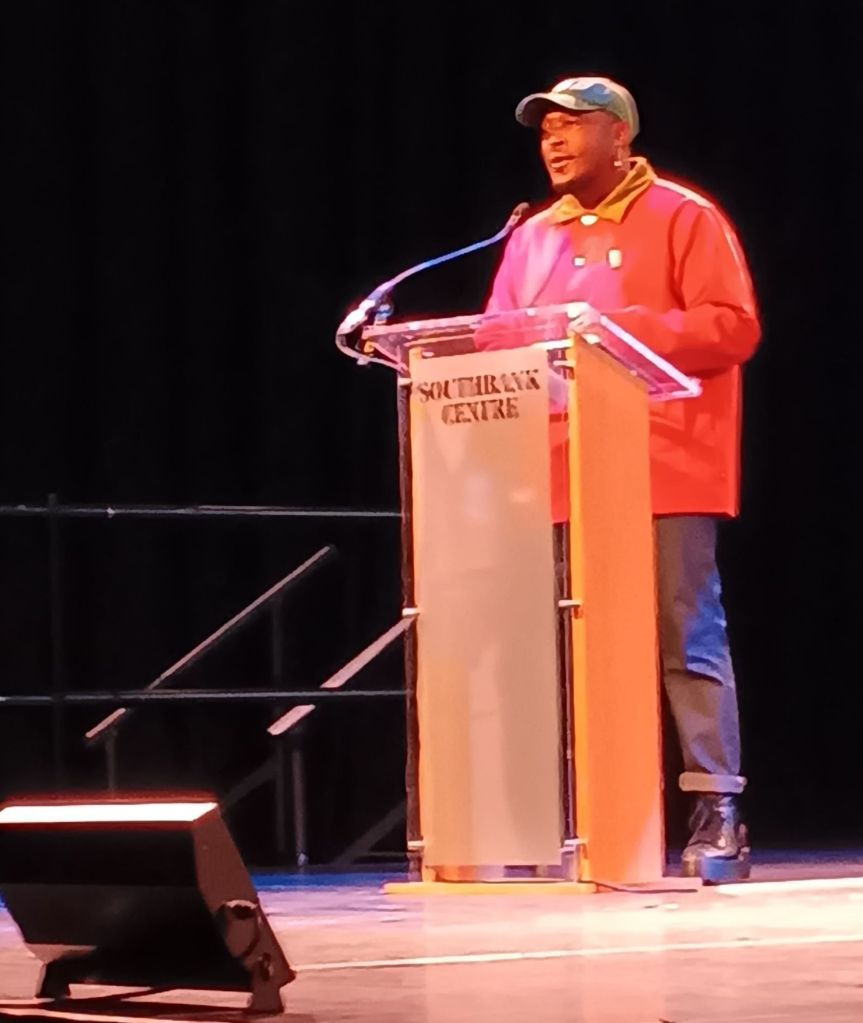

The seats were empty, and then Danez entered making straight for the lectern, until he realised his interlocutor was not yet with them. Meanwhile he told us about getting caught up in the police action protecting the English Defence League action in central London protesting the arrest of Stephen Laxley Lennon, that white middle class racist who calls himself Tommy Robinson to appeal to his racist supporters the more. How much more ugly, said Danez , is that kind of hate than in the face of old ugly white men – maybe! Though the Black face of the Tory party can be as ugly at the moment it puts on White airs. I feel a need – felt one then – to get beyond the nuanced binaries, though we have, we just have, to understand the main responsibility for this lies in whiteness of the ideology of the benefits of White cultural history bluffing us it is the history of all of us and not just the privileged few.

Once Danez was reading the world stopped, especially in reading Sioux Falls. It is probably, in my view, nearest the greatest poem of the half-century we will find when we get there, if I do. However his explanations of poems of place amazed, and the event wheeled inevitably, guided well and correctly by Victoria, to that wonderful long poem soon (pages 120 – 136) which Danez spoke of as a poem about love that sees a future beyond binaries, ‘somewhere my Black can fall off’. That somewhere eden isn’t here yet and never has been. Nor is it visible or sensible in any way or ways, as true edens are not; a utopia ( a no-place’) that is some place sometimes whenever but not yet -soon perhaps. It is a poem, Danez says, about the sins of ‘us and them’ as they both give way to a fuller transition fom here and now to a time and space where the question – ‘is i we’? – can be answered in the positive. This is a brutally intelligent poem pared down to just what counts.

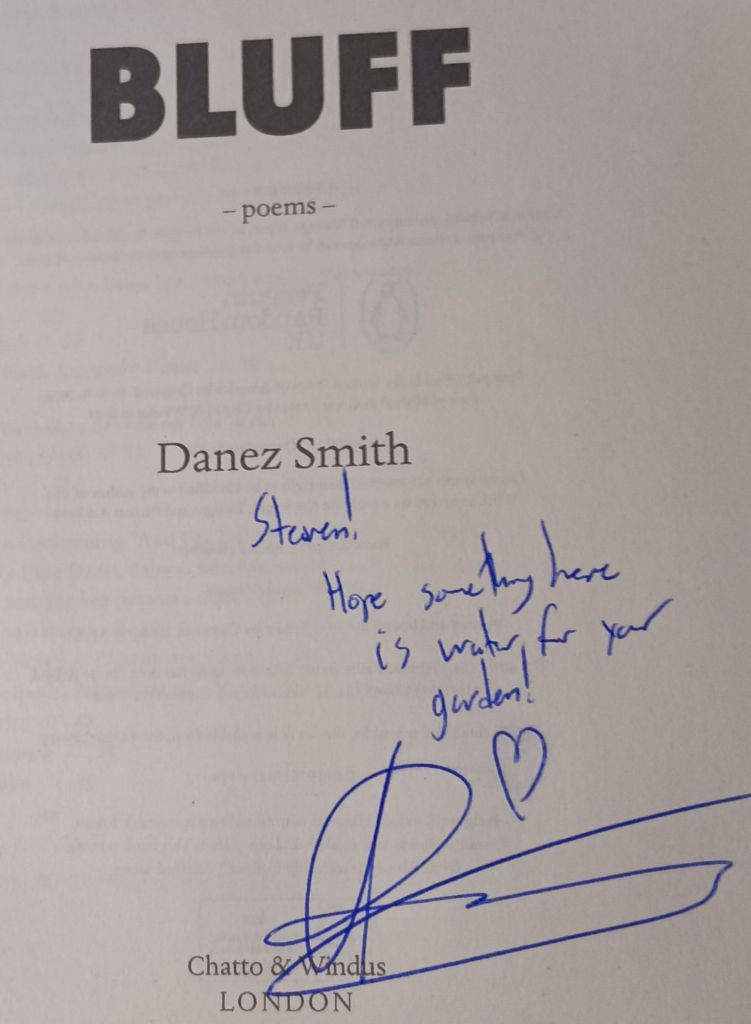

Danez signed my Bluff. I will find hope in the water that runs between us.

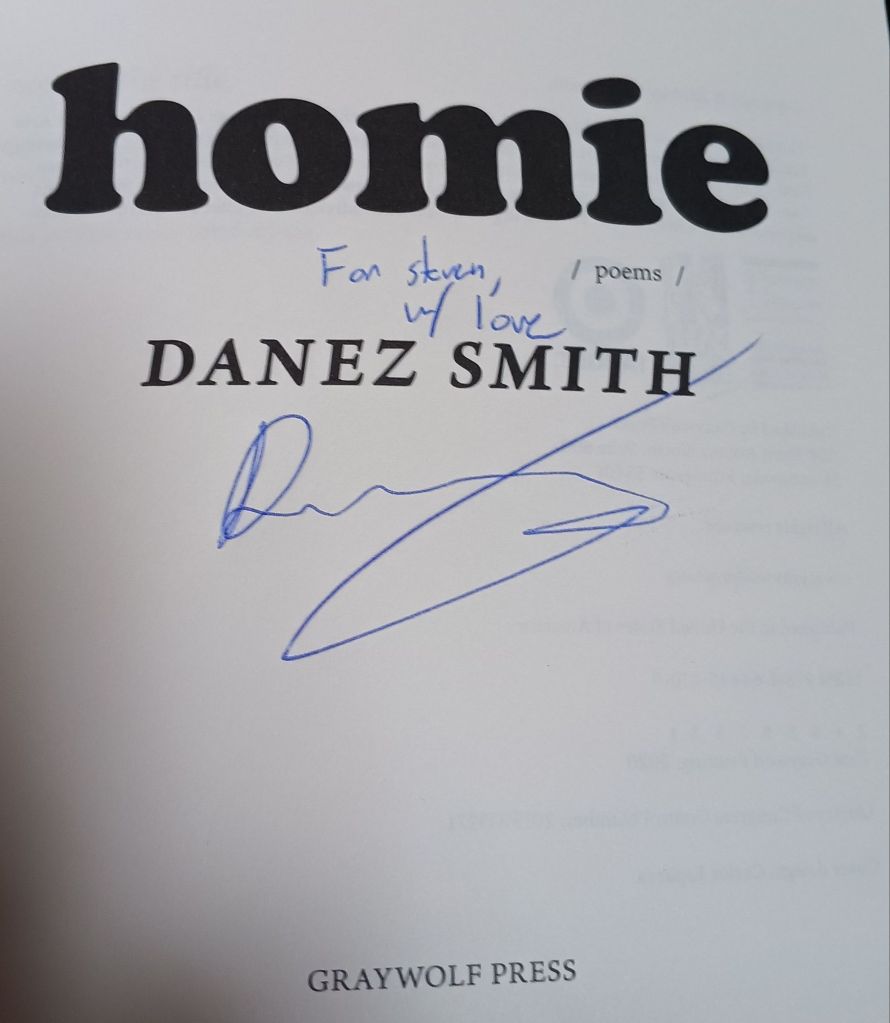

He signed my Homie and I love the love I feel in it.

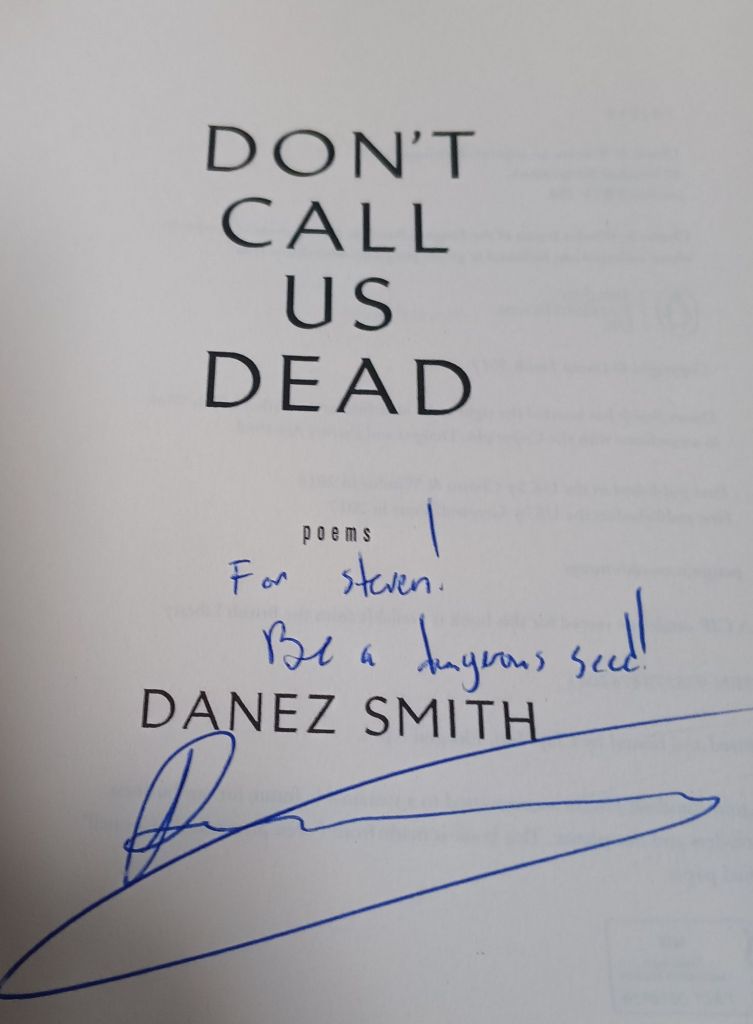

He signed my Don’t Call Us Dead and I feel already a more ‘dangerous seed’ than I was.

And now I am home and wishing I could talk to Danez. Here more about the things he touched on as he spoke – the effect of his HIV diagnosis, the collapse of his ‘marriage’ and his seven-year writing silence, his new lover and to try and drink from the river of his wisdom and intelligence, an intelligence like Andrew Matvell and Walt Whitman combined if you can imagine it.

Love you, Danez,

With love

One thought on “On seeing Danez Smith”