The White Heat of WES or the STREETING of the Blair Witch Project

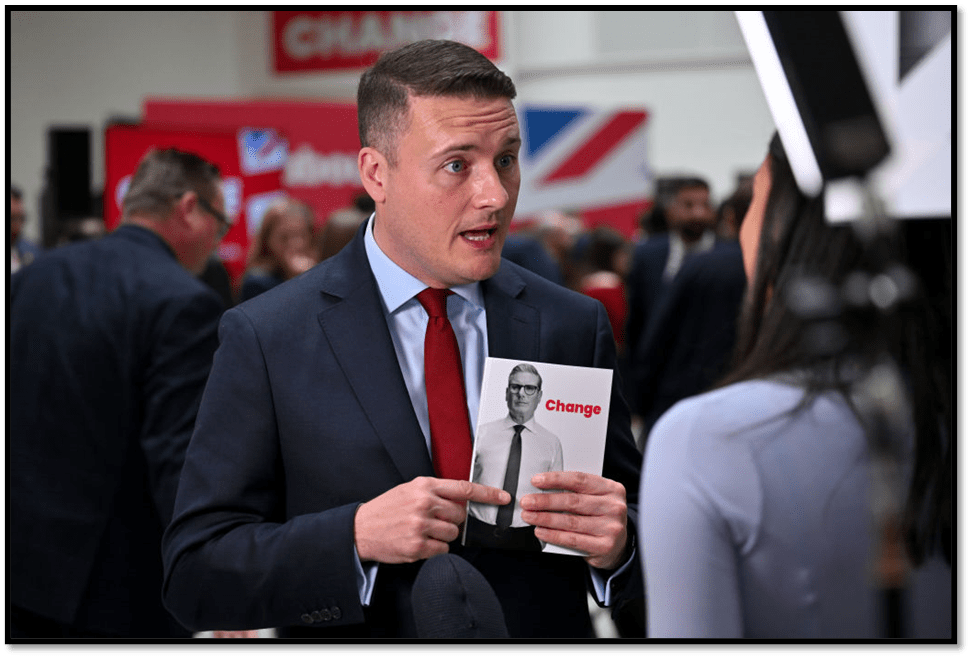

Two days ago Wes Streeting outlined the approach the Starmer government will take to implementing its key pledge to voters – the relaunch of the project called The National Health Service, although it is yet to be seen how clear are the objectives to integrate this with a National Social Care Service, or what ‘National ‘will mean in either putative concept. In the latest announcements the lead concept in understanding the institutional role of the NHS will be the devolution of much service provision to local, called by Streeting ‘neighbourhood’, health services. Here is the vision in Streeting’s words, as recorded by Christopher McKeon in The Standard.

“Our 10-year health plan will turn the NHS on its head – transforming it into a neighbourhood health service – powered by cutting-edge technology that helps us stay healthy and out of hospital. We will rebuild the health service around what patients tell us they need.”

Some areas of Labour’s plan have already been sketched out, with perhaps one of the biggest being the creation of new neighbourhood health centres.

These are intended to be based closer to people’s homes than their nearest hospital and enable them to see GPs, district nurses, care workers and other medical professionals in the same building. [1]

The words have a homely and comfortable ring. However they describe also the Primary Care ‘polyclinics’ set up by the last Labour Government. Theze were experienced by many people using them as being as remote as ever, because too thinly dispersed between large Primary Care Trust (PCT) areas. Some were merely carbon copies of existing inadequate services with gateway thresholds that were not perceived as helpful and involving working arrangements for personnel that never quite got any consensual agreement amongst the professionals supposed to staff them.

There is always an issue with ideas of reform that are conceptually led by ‘buzzwords’ and significant dangers in one of the being ‘neighbourhood’. According to Streeting, quoted by The Financial Times on the 7th September 2024 and echoed by Stephen Kinnock on morning TV on 21st October, the key words for this reform are represented each by 3 shifts needed by the NHS are each from one extreme of an imprecise binary to its opposite. These binaries are represented by buzzwords – and at that point ‘neighbourhood’ was not one of their company.. Community was present however in the reforms started with the NHS Plan of 2000.

Speaking at the Financial Times’ Weekend festival in London on Saturday, the UK health and social care secretary said the new government would prioritise moving NHS treatment “from hospital to community”, “analogue to digital” and “sickness to prevention”. The three shifts “are absolutely necessary, and actually existential . . . for the future of the NHS”, Streeting said.[2]

The fact that they are mooted as ‘existential suggests that their alternative is the extinction of the NHS. For a government to say this is of extreme concern for it seems to limit the options, even of a supposed consultation on what these changes will mean in practice. Meanwhile, whilst they remind the government that considerable costs are involved in not only reform but addressing neglected decline in hospital services with funded renewal, health managers, like the Chief executive of NHS Providers, Sir Julian Hartley still praise the direction of movement. His words, to The Nursing Times, are a little more explanatory, and not as relevant on the government’s choice of binary buzzwords, in describing those ‘shifts’ desired of a reformed health service. “The renewed focus on creating a digital NHS, focusing on prevention and public health, and ensuring patients are cared for closer to home is a step in the right direction,” Mr Hartley said.[3]

But the key word is renewed, for all of these plans were those of the last LABOUR Government, and all met serious obstacles. Moreover they also are all of questionable viability: especially the most problematic of them all (expressed in old-fashioned terms by the government) ‘analogue to digital’. The publication Digital Health is much wiser about this specific issue and they point out the dangers of woolly old-fashioned thinking, as if the NHS were starting from scratch reforming an analogue system to a digital one. These digital systems have long been in operation. The point is they are set up so that they cannot speak to each, whether between health and social care or even different domains and regions of the NHS. Digital Health says:

It isn’t as much a shift from analogue to digital, but a move from disparate digitisation to whole-scale transformative implementation.

There are so many great examples across the country of Streeting’s vision of a digital NHS, from North East London Foundation Trust’s approach to virtual wards which uses tech to bring together remote patient monitoring, bed management and discharge services, to the rollout of digital social prescribing across Birmingham and Solihull Integrated Care System (ICS).

However, too often, these are isolated examples that reflect locally driven needs because of the very nature of service demand and commissioning models.

What needs to be prioritised is the right investment and reform to empower the NHS to scale digital and data in a way that it doesn’t continue to mimic the silos already in existence within care settings.[4]

Those silos were intractable in last attempts. Moreover, the supposed need for them to maintain independence of each other is still defended on ethical, especially the ethics of confidentiality for service users, and other grounds of principle by professional health and social caregivers. They rarely get talked about outside the silos and hence are even more resistant to change.

In my experience multi-disciplinary work involving disparate agencies like health, social services, housing, police, can become completely impossible under these conditions, but it is even more dispiriting to see regions of HNS unable or unwilling to communicate, even more so in the case of primary, secondary, specialist mental and learning disability services that don’t talk to each other.

And this stumbling block applies to the other priorities too: “from hospital to community”, and “sickness to prevention”, for how can the goals of such a transition be served when too little is understood about how and why inter-service and intra-service communication breaks down. The obvious example is in child protection where these breakdowns are blamed for every failure of the system. Despite frequent tragedies and reports making that point again that ptofessionals failed to communicate, nothing has changed before the next instance.

Social prescribing, praised by Streeting, involves communication between agencies in many sectors – private, voluntary or not-for-profit. That communication will be essential for better prevention and for community interventions in the sectors of housing, employment, leisure and so on. Yet such inter-agency work raises even more areas of weight relating to the knowledge partners in any one package of care have of their function in any one cate package and the particukar risks or benefits of delivering the service in certain ways for the person or group involved – especiality when impersonality and remoteness, for instance, may be the chosen form of delivery.

So why do Labour governments in particular put such faith in the re-calibration and changed management of services to deliver answers to complex questions? In part the answer lies in the sensitivity of Labour to the charge that they ‘throw money at services’ and thus make waste and inefficiency inevitable.

Another comes from their reluctance to be associated with relaxed attitudes to issues of budgeting and debt. Their answer has been to put faith in the management of public services and to replicate in it some of the features of management in the private corporate sector. That belief system tends to get called ‘managerialism’.

Another reason is that Labour fears being viewed as an old-fashioned party tied to the ideologies of socialism from the nineteenth-century. It wants to be the part of applied science in particular – a believer in new cultures, ones that sweep away old institutions, old beliefs, and hide-bond forms of thinking. It is almost as if the party at times wants rid of the anthem we call the Red Flag to replace it with the verve of Tennyson’s bells in In Memoriam, and even some of his meanings (especially in instructing the bells to ‘ring out’ a ‘slowly dying cause; and ‘ancient forms of party strife’.

Ring out the old, ring in the new, Ring, happy bells, across the snow: The year is going, let him go; Ring out the false, ring in the true. Ring out the grief that saps the mind For those that here we see no more; Ring out the feud of rich and poor, Ring in redress to all mankind. Ring out a slowly dying cause, And ancient forms of party strife; Ring in the nobler modes of life, With sweeter manners, purer laws.

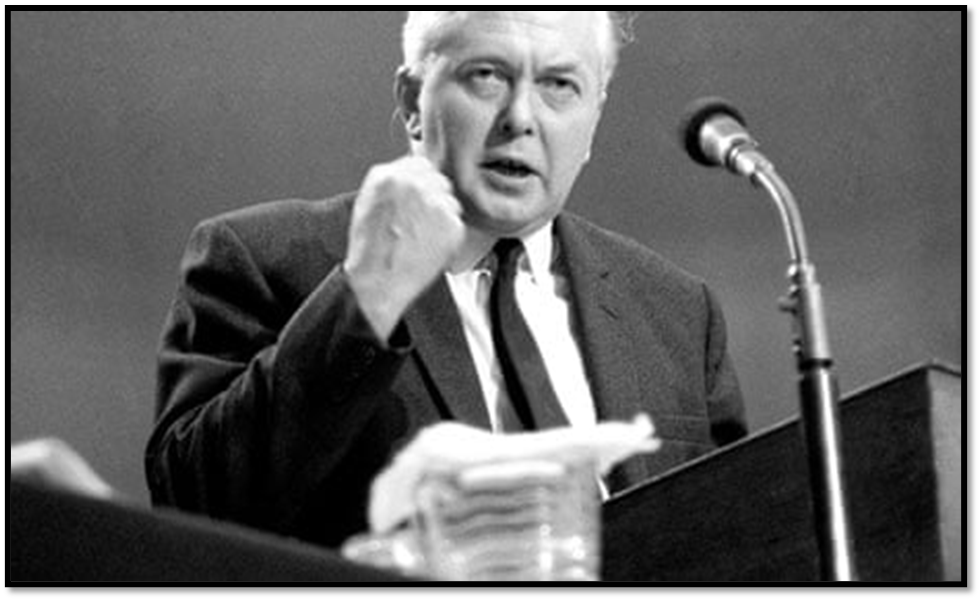

One of the most controversial pieces of legislation in the first attempt at party renewal, in the 1970s under Harold Wilson was an attempt to ‘modernise’ labour relations with legislation based on a white paper called ‘In Place of Strife’. Wilson knew he needed to create an ideology that modernised the Labour Party; make it look like the force for something new, not a rehash of what was being thought of as old values.

He chose to enter into in a debate between C.P. Snow and F.R. Leavis, one representing the culture of science and technology, the other harking back at a time of past values. Matthew Francis described that debate and Wilson’s entry into it in a Guardian article in 2013:

In 1959 the novelist C P Snow had used his Rede Lecture to claim that British social and political elites were dominated by “natural Luddites”, whose ignorance of science and engineering made them singularly unfit to govern a world in which technology was becoming ever more important.

A book based on Snow’s lecture quickly became a bestseller, and the debate was reopened in 1962 when the literary critic F R Leavis dismissed Snow as being nothing more than a “public relations man” for science whose “consecrated public standing” was out of all proportion to his intellectual gifts.

The identification of the enemies of progress as ‘Luddites’ was a key symbol for Wilson’s rethink of Labour as a movement. No longer antagonistic to the symbols of technological innovation and the advance of capitalist production it facilitated, he spoke to a scientific conference leaving his best known lines to the end: ‘Wilson warned his audience that if the country was to prosper, a “new Britain” would need to be forged in the “white heat” of this “scientific revolution”’.[5]

Of course for Labour the ‘old-fashioned’ bulwark of the ‘dying cause’ was Conservatism and Wilson had a point – the Tory party was mainly patrician, male and aristocratic, until Margaret Thatcher took up similar cudgels with its old guard. But, be in no doubt, Wilson wanted to align Labour too with a party of government – not of ‘protest’ -: a force for the middle way that would embrace and redeem the worst excesses of capitalism and humanise it but NOT destroy it.

After Thatcher, however, it was not possible to characterise the Tory Party as that of aristocratic and backward looking values rooted in the land. Thatcher had made her party a party of business and science (she credited herself as a scientist). The best of leaders for Thatcher was someone who managed the nation as a good business person managed a profitable business, with foresight for trends and adaptability to changes in the market. And there was nothing in the world that could not be characterised as a market, nothing good in the world that was not best treated as a commodity for her.

And yet, though Thatcher represented a new entrepreneurial class she could be accused, as Tony Blair knew, of a kind of closedness to modern technocratic and meritocratic values, other than to anomalies who emerged through a rotten system like herself. She was not going to aim to breed an army of Thatchers, for her aim was to implement the neoliberal cause: to reduce the value of the ’state’ and ‘society’ as agents, freeing up the energies of individuals and families. There were only individuals and families whose value differed as if by virtue of the biology that actually created, in her view, the class system.

For Tony Blair on contrast, modernisation was the theme and it would be served not by one leader alone but the principles of modern governance in all domains. Blair was not even totally antagonistic to neoliberalism but felt the role of the state was to facilitate and manage fluidity in society that ensured interchangabity of persons in social or work roles by virtue of social and class mobility. Hence ‘Education, Education, Education!’.

And the content of education was to be modernised too, and would teach how a fluid society was both to be appreciated and managed to avoid chaotic counterflows of energy battling against each other. The ideology of Blairism – the modernism of the Modern Labour Party – had to be called ‘New Labour’ to identify ‘Old Labour’ as an enemy of progress and good management of party and nation. At last, Blair must have thought, I will ‘Ring out the old, ring in the new, / …/ Ring out the false, ring in the true’. It is a mistake to think of Blairism as the opposite of Thatcherism. They had so much in common that some analysts discussed both under the term, ‘Blatcherism’.

Blatcherism can be defined as an emphasis on free market policies, support for Privatization or the private ownership of former public services, a monetarist/neo-classical economic policy and a retention of anti-trade union legislation. … Under Blair’s leadership, the party abandoned many policies it had held for decades and embraced many of the measures enacted during Thatcher’s tenure as Prime Minister, including the Building Societies (deregulation) Act of 1986. In conjunction with Peter Mandelson, Gordon Brown and Alastair Campbell, Blair created the New Labour ethos by embracing many aspects of Thatcherite beliefs into Labour as the “Third Way“.

Both ideological positions clearly prioritised the free market, and deregulation as a route to it, and the optimisation of any regulation which was thought of as a ‘restraint of trade and production’. Consider that Keir Starmer too called recently for ‘a bonfire of red tape’ in a business conference, without any sense of how such a policy under Cameron led directly to the bonfire that Grenfell Tower became. Both parties are committed to the ideology we call ‘managerialism’ now.

The best definition of ‘managerialism I found recently was in an article in Studies in Higher Education, In its onset managerialism was crucial in revisioning many human change practices in which plasticity of identity matters, in mental health for instance. Sue Stafford in that paper puts it thus:

Managerialism … represents a certain worldview or ideology, where the latter is taken to mean a ‘consistent integrated pattern of thoughts and beliefs explaining man’s attitude towards life and his existence in society, and advocating a conduct and action pattern responsive to and commensurate with such thoughts and beliefs’ (Lowenstein 1953, 52). Thus conceived, an ideology is action-oriented, intended both to influence opinion and to justify and legitimate a course of action (Gerring1997).

If time and resources, including ‘human resources’, can be managed better so can anger, depression and anxiety because this is an ideology not a practice as such. It guides practice. Hence, managerialism is an important issue in all public services for both envisaging the content of educative interaction with service users, patients and learners, but also the creation and nzintebance of work teams and its various task in any case in which project management is called for. Notably the services were education, social services and the NHS, with managerialism chosen as the main ideological engine in the creation, delivery and evaluation of change towards efficiency and practice at ‘best value’ in such organisations. But Stafford points out that managerialisation, as an application of magerialism, is applied in specific and characteristic ways:

… via the application of specific techniques or ‘control technologies’ in the form of practical measures (such as target setting or performance management), new organizational structures or propaganda and persuasion designed to effect cultural change (Deem, Hillyard, and Reed 2007, 14)… These management ideas are said to have ‘mutated’ into managerialism under the following formula: Management + Ideology + Expansion = Managerialism. (Klikauer 2015) ….. In so doing, it has provided an apparently managerial solution to what were previously conceived of as political problems (Pollitt 1990).[6]

These factors are I think definitive of what I call The Blair Witch project – witch because it is based on the expectation of transformation of frog to prince through application of its spells. Lots of its mantras are invoked by the present Government under the title it now prefers as the ‘changed Labour Party’ – a party changed by managerial methods.

Its NHS reforms are in the same mould, though not unlike the NHS Plan of 2000 and its sequelae. Wes Streeting is probably the face of that modernisation. Expect from the consultation and the description of the new NHS as an outcome, that many of the terms I cited above will appear as a presribed result: ‘target setting, performance management, new organizational structures, propaganda and persuasion designed to effect cultural change and the driving of the whole through the transition from analogue to digital. Much of the delivery of service, where possible, as well as the process may be digital as an index of ‘best value’, community involvement in ‘care packages’ will consist of much that is no more than signposting to a service that may ultimately not exist or not be appropriate for personalised needs. These ‘services’ will show up nevertheless a service claimed to be delivered and coordinated in a managed manner.

The choice and evaluation of a service will use measurable quantities as its markers and these also may assess for ‘best value’ in a service. The ideology can justify itself quite easily by such measurements which rarely equate with real concepts in health such as the curative, therapeutic, amelioration or palliation, matters based often in the quality of relationships not the delivery of quantifiable units (even if these be measures of satisfaction). More importantly, managers not clinicians or even advocates will decide what works and what does not and will ignore the lessons of importance of relationships in health that cannot be measured.

And this is where Wes Streeting is heading I truly believe – to a modern health and social care service that meets the minimally expressible need. But in health and social care so much is inexpressible, to say nothing of being unquantifiable. But look – this is the future being forecast by sleight of hand. The question as Streeting and Starmer tell us is existential. Take this that I offer and survive services ,,, or have NOTHING AT ALL. Whether you survive or not will only matter if you belong to a sufficiently measurable group of customers suited to the service’s measurements of its prescribed limited availability.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Christopher McKeon (20 Oct. 2024) NHS will become ‘neighbourhood health service’, Streeting pledges | The Standard available at: https://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/nhs-government-wes-streeting-health-secretary-labour-b1188909.html

[2]Franklin Nelson (2024) ‘UK health minister says NHS needs to make ‘three big shifts’ to survive’ in The Financial Times (September 7 2024) available at: https://www.ft.com/content/1e71c913-4dea-4088-878e-4d3e2889b875

[3] ‘Streeting lays out plans for improving NHS and social care; in Nursing Times available at: https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/policies-and-guidance/streeting-lays-out-plans-for-improving-nhs-and-social-care-25-09-2024/

[4] Digital Health (2024) ‘Why Wes Streeting’s shift from ‘analogue to digital’ isn’t the answer (digitalhealth.net)’ (30th September 2024) available at: https://www.digitalhealth.net/2024/09/why-wes-streetings-shift-from-analogue-to-digital-isnt-the-answer/

[5] Francis Matthews (2013) ‘Harold Wilson’s ‘white heat of technology’ speech 50 years on | Science policy | The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2013/sep/19/harold-wilson-white-heat-technology-speech?ref=pmp-magazine

[6] Sue Shepherd (2018) ‘Managerialism: an ideal type’, Studies in Higher Education, 43:9, 1668-1678, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1281239 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1281239 © 2017 The Author(s). Published by Inform Or: Managerialism: an ideal type (tandfonline.com) https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03075079.2017.1281239