Amy Liptrot in The Observer on the 22nd September says of the film based on her personal story, The Outrun, that it has transformed themes in her life ‘into art, something bigger than me: ….. One of the themes of The Outrun is the link between mental illness and addiction and the desire to reach for extremes. This film-making process has been another example of these extremes. I am amplified, cinematic, extra-real’.[1] Geoff and I saw The Outrun at Gateshead Metrocentre Odeon at 2.30 on Sunday 29th September 2024.

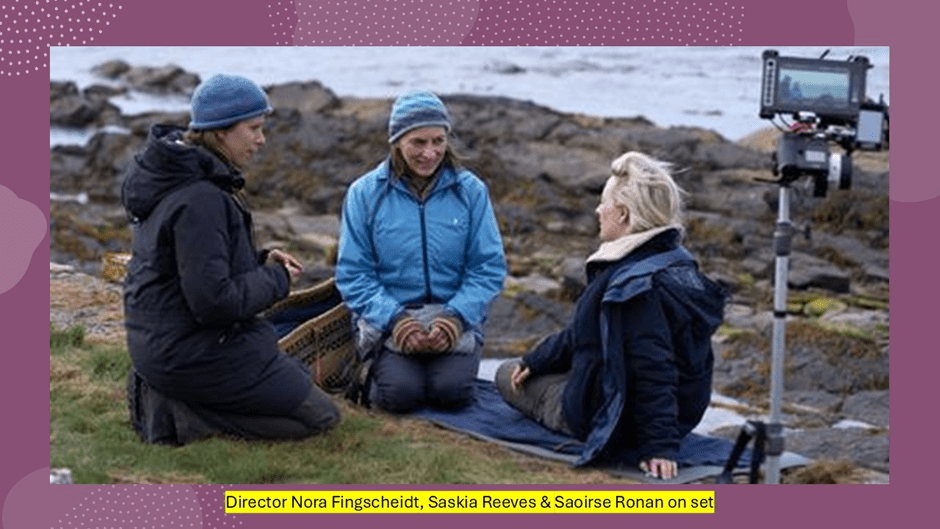

I have already blogged on The Outrun twice – one blog on the book by Amy Liptrot, the other blog on the theatrical version which played at this year’s Edinburgh International festival and staged by The Edinburgh Lyceum Theatre Company (see the blogs by clicking each appropriate link above). The media being so different you expect different things in each but I cite in my title Amy Liptrot’s own view of the film, in which she was involved as co-writer of the screenplay and creative consultant with Nora Fingscheidt, the rising-star German director hired by the producers including Saoirse Ronan who intended to play the role based on Liptrot. Liptrot tells us that she and Nora were determined to refer to the character as if a third party, not related to Amy directly and called her Rona from the start: ‘I began to see Rona as a collaboration between me, Nora and Saoirse: a new entity’, says Liptrot in the interview.1

Emily Zemler of The Los Angeles Times adds new information about the process of the film’s making based on interviews with Nora Fingscheidt:

Because English is a second language for Fingscheidt, she wrote the script loosely, without specific dialogue, leaving it up to the actors to know what to say.

“It was a bit unusual for me to work like that,” says Ronan, who wrote many of Rona’s lines herself. “But because I would love to make my own stuff, it gave me a bit more confidence to know that when it came to that stage of developing a film I wasn’t completely clueless. I could find a way to use my own voice and translate that into dialogue.” (5)

That much of the film was written in this collaborative manner, even with the real Orcadians who Nora cast to play versions of the people of each island, especially Papa Westray (referred to often as Pappay), the most remote and unpopulous of the islands (estimated at 60 persons). Liptrot thought this casting gave greater Orcadian depth and integrity and I think I agree, but it excelled in the treatment of the theme of the book, the play I saw and this film that personal psychology can be redeemed by genuine community that challenges one’s habitual versions of yourself whilst supporting new ones – in swimming for instance or community events. Stuart Kemp in Screen Daily cites his interview with Fingscheidt before the film’s release. The ‘Muckle Supper’ is described in Liptrot’s book but both Liptrot and the director gave way to the real experts on island customs.

To recreate a Muckle Supper for the film, Fingscheidt handed complete creative responsibility over to the Papa Westray people. “They all came together, friends and family, from other islands too. They danced and the local band played and we became more like a documentary unit to film it,” she smiles. “When you think people centuries on are dancing the same dances, it becomes something spiritual in a way and not something that’s just fun and entertaining.” [2]

Fingscheidt’s ambition for a ‘spiritual’ take on the role is very much a characteristic of the film despite the gritty realism of its scenes of the visceral effects of alcohol and drug consumption and the risk of dangerous exposure to sexual abuse, all played directly and sometimes without the kinds of filter we are used to.

The symbolic role is taken on by Orkney – not just its people, but small-holding buildings, boats and harbours and its animal and plant populations. The landscapes and seascapes of its coastal character, and some hybrid forms of those elements that come from a folklore still respected in the Orkneys, at least in the remoter parts, also play a part. Some of this latter element is not to the taste of some critics, such as The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw who compares the scenes he likes about Rona’s time in employment with The Royal Society for The Protection of Birds (RSPB) with the scenes referring to Orcadian folklore:

Ronan’s unassuming scenes with the RSPB, apparently using non-professional actors, are the very best thing in this very good film – better, for me, than the slightly self-consciously dreamy voiceover passages about Orkney mythology, selkies and various legendary creatures, sometimes accompanied by animation.

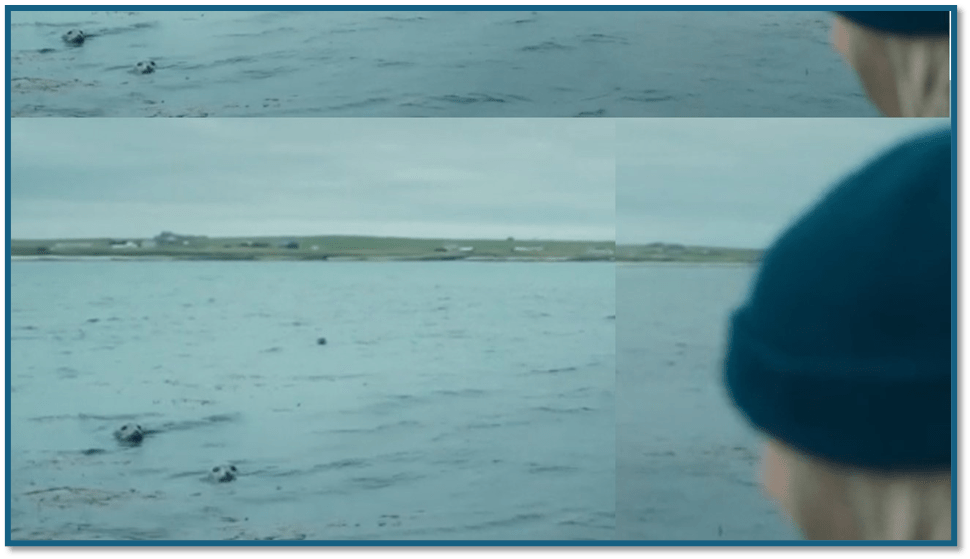

The animation, I have to agree, worked less well for me than the treatment of selkies; mythical creatures from the sea who can abandon their seal-skin to dance as human and naked on the land but who cannot return to the sea if seen and desired by a human being. It does not surprise me at all that seals are anthropomorphised. In the film we exchange gaze with seal eyes just above the surface of water or misrecognise their bifurcated limbs forming a means to swim underwater. These featurs must surely lie behind such sexualised myths and hence I do not have Bradshaw’s resistance to these myths.

The selkies work in the book and they work brilliantly in the film too. This latter opinion is expressed simply and beautifully by Mireia Mullor in her review in Digital Spy, and certainly not antagonistically as by Bradshaw:

The movie is packed with symbolism connecting nature and humanity, as well as science and myth, in order to portray Rona’s state of mind.

It utilises Celtic mythology and Orcadian folklore to frame her story, even indirectly comparing Rona to a selkie at the start of the movie — magical creatures of the sea that, if trapped in human form, are cursed to be “always discontent” since they belong in the sea. It’s a poetic way to explain how it feels to be inadequate in one’s own life, and not knowing why.

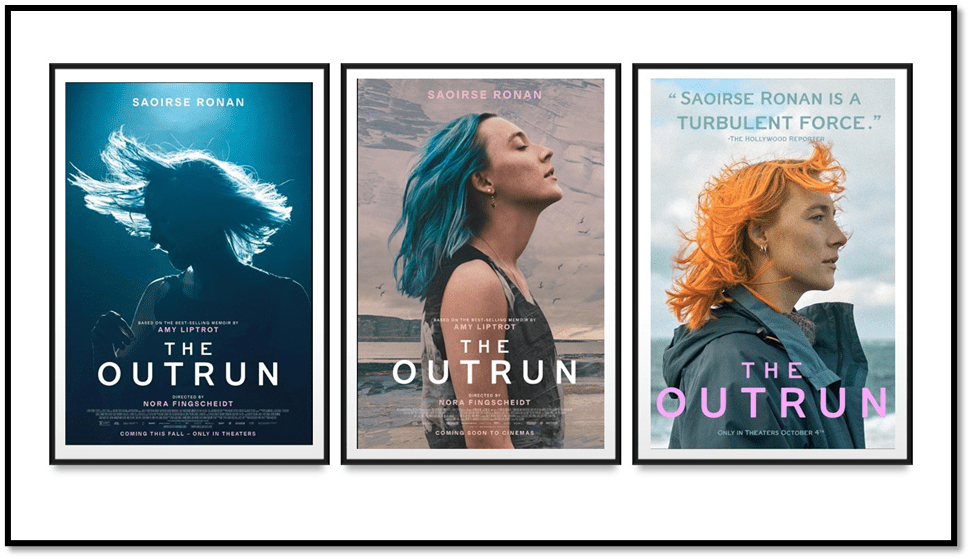

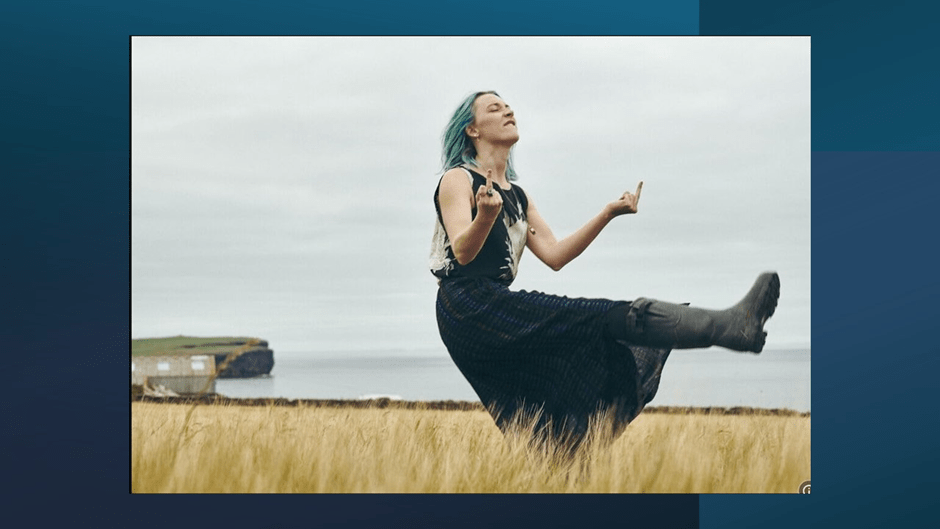

The idea that Rona is a lost selkie connects with the significance of her ever-changing hair colour, which tells its own story in The Outrun.

The blue hair gradually disappears as she sinks deeper and deeper into her addiction. Her connection to that blue (which might symbolise the sea and perhaps her true self) is severed as she loses herself and her hair turns orange.[3]

I think mythical symbolism is possibly the perfect way to deal with the theme of the cusp between our perception of a world to which we are habituated and one by which we can still be surprised and has the feel of fantasy. The transition to the fragmented world of enduring mental illness and its link to alcoholism and other unregulated features in human desire and appetite takes hardly a moment from recognition of that contrast in how most humans at some point see the ‘real’ world.

I think it is more difficult to do such symbolism in a play, even Ibsen fails us sometimes, or a film, and in many ways it was absent as a feature to be expressed in the Lyceum Company’s play at Edinburgh. They substituted for it an explicatory framework based in intensities only of interactive human family and community dramas. But in the film, mythology is often evoked purely through the collaged and serial symbols of pounding, raging seas, the structure of cliffs and bare landscape, and mounting threatening clouds. Speaking to Aoife Daly of The Irish Independent, the film director points out that this is so, in part at least, because the chaotic and wild in nature can so easily take on a psychological aspect for a character looking at it, and feeling,it within in less easily visible interior spaces. Daly quotes Ronan to say, for instance:

“There is this sort of chaos and wildness to the Scottish land and the weather, and the weather on the Orkneys in particular, which sort of serves as like a mirror to her emotional state.”[4]

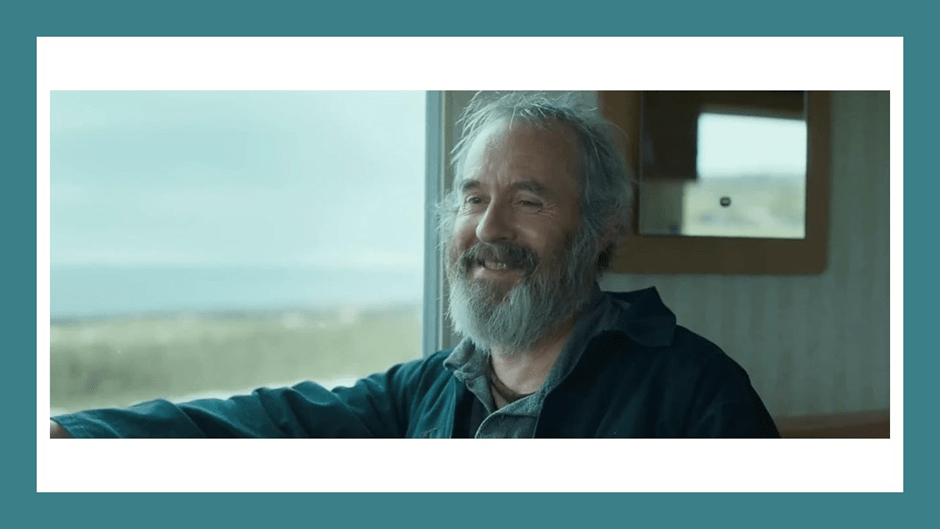

But surely more than a flat mirror, for the turbulence in the island is within (in those cavernous hollow underground spaces where the sea resounds). The myth of the Muckle Worm, shown as an animated cartoon to simulate a child’s understanding in flashbacks, tries to show this idea perfectly, though its timbre fails to fit the film’s orchestration of the emotions involved. The fear of a father who in extreme mania rages at external nature is better seen as sucessor to King Lear, but who at other times is a more peaceable patriarch, who does not cope with turbulence well. Stephen Dillane is brilliant in the role.

In Liptrot’s book the narrator’s Dad finds some accommodation with the swings of his mental condition outside of medication. The last we hear of him in the character based on him in the film is his false accusation on the telephone to Rona that it was she who told the police to attend him leading to his hospitalisation under a section of The Mental Health Act. Rona is unable to shift that fixed belief in her Dad, at keast whilst he remains mentally ill.

I do not know whether it is an issue we should care about that Liptrot’s Dad finds more resolution in the books description of his fate than does Rona’s. The point of it all is that redemption of any kind in life can be sketchy at the best. Rona’s mother, in the hands of a brilliant Saskia Reeves, is a much more empathetic character in the end than the mother in the book; at least when not seen in the dark light of her patronising young circle of young people who have found God and a sickening showy contentment.

I think Daynin (played with tremendous power by the gorgeous Paapa Essiedu), Rona’s lost love in London is in the film allowed some light of resolution in his friendship with Rona that seemed absent from the play version and, I think, the book, where his equivalent character has a more realistic refusal of engagement with the narrator if he is not to prompt co-dependence. The treatment of the character’s refusal of co-dependence is stunningly beautiful if idealised in the version that is Daynin, as are visions of him in a kind of selkie-like imaginative life in Rona’s undersea imagination later.

The film though deliberately shifts other characters from any limelight they might ever have had, except as representations of the issues that help to manifest Rona’s interiority, and perhaps some of its causation (at least in the case of her father). The scene where she is remembered as a child observing her Dad violently confronting an Orcadian storm, and inviting it into his house, his family and into him through a window he, as he drinks, shatters, is meant to be indicative I think of a facet of what Rona introjects and never quite loses. There is nothing quite like that in other versions of the story I have read and seen. It stunned me emotionally.

By the way, the process of film-making enters here into our interest because it emphasises how important was that exterior symbol of Orcadian wildness to the film’s thematic content. The actual mildness of Orkney’s very unpredictable weather at the time the crew visited was a major problem, especially given the impossibility of transporting huge heavy wind machines to remoter islands. Stuart Kemp’s interview with Fingscheidt captures the dilemma brilliantly and shows the lengths to which it may be necessary to go to make the symbolic use of weather work in a major budget film:

One of the biggest challenges shooting on Orkney was the weather was too good.

“We wanted and needed storm roughness,” Fingscheidt says. “Our main shoot was in summer, Orkney was blessed with really good weather. We had very little wind, wonderful blue sky, sunny days.”

In the end, the production got lucky. “On the very last shoot weekend, there was a little gale. You also always have to balance if it’s too windy, you can’t go with the film team close to the cliff edges but you need a certain amount of wind that looks dramatic on the camera.”

Another occasion required a gale to be blowing and rain lashing against the cottage windows. “In reality, it’s a leaf blower and hoses spraying water against the windows,” Fingscheidt smiles, …

It is very much a film about Rona, and, as a result perhaps more interesting psychologically, in exploring that theme of the ‘on the edge’ nature of the narrator in Liptrot’s book. This is even explored through wonderful cinematography on the edge of Orcadian cliffs. Think through, for instance, the director’s insistence on threatening her crews safety at the edges of cliffs in the quotation above.

Mainly demonstration of inner wildness is done in the film by the reflection (hence the mirror metaphor), as Ronan says in a quote I gave earlier, of the supposed ‘chaos and wildness’ of Orkney landscapes and climate. Stuart Kemp cites Fingscheidt as saying to him: “The islands are a character, nature is a character in the book”, and it seems her ambition was to make it more so – the only symbol universal enough to be capable of summarising Rona’s interior life of orchestrated wildness, something she lives in, even in ‘sobriety’, and which shows that sobriety is not the word that truly characterises Liptrot’s narrator nor Rona.

At the end of the film shots of the island are intercut with the highs of an alcoholic’s party life, huge waves are seen to thunder, though we are reminded that even they can rage only to a certain height before collapsing. Rona is seen to conduct (orchestrate even in the metaphor I used before) images of wildness and chaos around her as her proper medium. You need to see the film to experience that alone. Stills tame the effect.

But Rona on the edge of a sea that is made to look, by inter-cutting to crashing waves, is how the film has to end and it is beautiful, chaotic and wild. It symbolically integrates into Rona’s sobriety some of that wildness and dissatisfaction with the tame that drew her to her addictions. The reflective Rona is also on a literal edge at other times. She ends the film with her hair colour orange, as above, and wedded to the sea like a vibrant selkie and Muckle Snake combined, raging fire at her head. At earlier points that relationship is literally a rocky one.

But elsewhere we see her reflectiveness as drawn to other dangerous edges, even the most hairy one of the balcony rail on which she sits and from which many in her position might have lost their balance, with or without deliberation.

And I think the collage above shows other edges – even interior ones in a darkened house, where Rona, through Ronan’s most exquisite acting, finds edges. The earphones through which music rages to fill her soul too are even important though the wild music is heard without them at the films most precipitous edge, the end of the film. At one point she stands at a window in her Pappay (a shortened version of Papa Westray) home and steers her room through a chaotic storm, as if from a ship’s bridge.

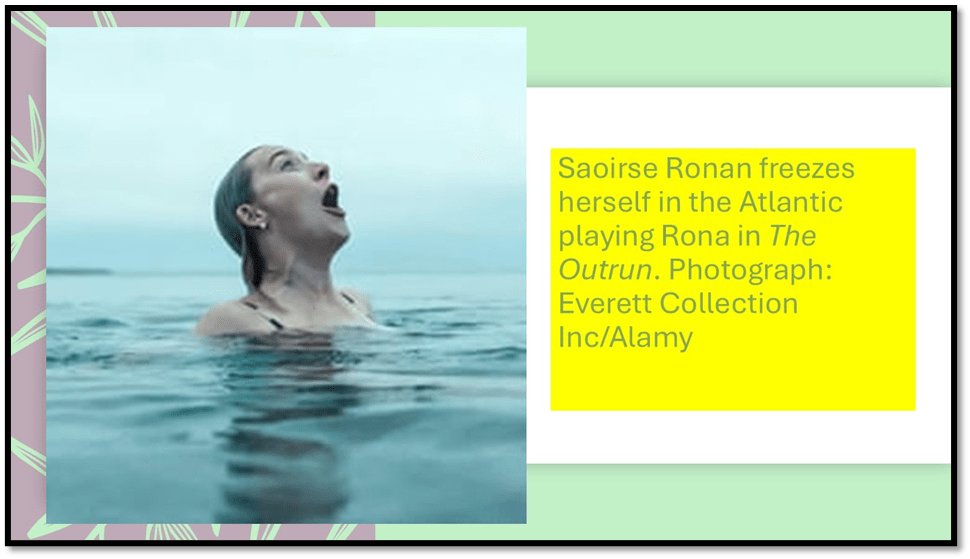

It is a telling moment but much more safe in fact than the wildness at the end, where only the illusion that you are conducting the elements as you would an orchestra stands between Rona and the wild seas to which, like any selkie she wishes to return. Though she does return to them, if only in accompanied swimming with a community. And those swimming scenes are exceptionally good.

But that woman puffing out as she rises from the sea is a selkie born into a world in which she remains uncomfortable. The abrasive, defensive Rona (a joy to watch because she is abrasive) is what she is with two single fingers up (one on each hand) to show what she thinks of the bourgeois world and what she seeks in alcohol time out of time, or later the imagination:

Bradshaw is spot on when he says: ‘Orkney is not sentimentalised as a rural place of innocence’. The crew went to Orkney at lambing time in order to show a lamb really being birthed with supposed assistance by Rona. It is a wonderful scene for it does not hold back from the blood, slime and edge of life and death prezent at any birth, a brutal moment. Neither does it spare us from seeing a dead lamb discarded into a huge dirty plastic tub.

Orcadians must be proud of how their islands are shown here – provided they do not buy into the sentiment sometimes associated with them. As they walk around Stromness, I expected to see the ghost of mild, timid George Mackay Brown hiding within the heart of an alcoholic lion his raging at the ills of life. But instead we get the nearest art has ever get to a noble womanhood of the Shakespearean kind, that he associated with noble men.

Rona is no Cordelia. Neither is she Goneril or Regan. She is woman exposed to the edge of terror by her own creativity and longing for all kinds of explanation for the terribleness in the world – but not to settle on one explanation (from science, mythology or psychology) but to orchestrate them all in a wild music.

Mullor expresses this aspect of the film best:

She often frames her ordinary existence with larger-than-life stories to make sense of her world, while also occasionally resorting to science to find some rational answers, like the technical explanation of why alcohol is addictive. Sometimes our problems are too big and unbearable to process, and our minds need different frames of understanding.

Do watch it. Yes, it has differences, large ones, from one’s expectations of a great film. Narrative takes too many inward turns perhaps but so you might expect from a life on the edge. To Emily Zemler of The Los Angeles Times, the director admitted that she had though that:

at first she thought the book was “unadaptable.”

“I had no idea how to structure this into a movie,” Fingscheidt says via Zoom. “Half of the film is this woman by herself on a tiny, remote island and it could easily become boring. But because [Saoirse] is one of the few actors who has the ability to hold that space, it gave me confidence that, actually, yes, this can work.” (5)

But it works. It works beautifully for me. I await my next viewing of it and purchasing the DVD.

With all my love Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Amy Liptrot (2024) ‘The Outrun: My real life as an alcoholic, played out on the big screen: My memoir is in cinemas this week, but what’s it like to see your life turned into a movie?’ in The Observer (Sun 22 Sep 2024 14.00 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/sep/22/amy-liptrot-outrun-life-as-alcoholic-on-big-screen

[2] Stuart Kemp (2024) ‘German filmmaker Nora Fingscheidt had never visited the remote Scottish islands of Orkney before directing Amy Liptrot’s 2016 memoir The Outrun’ in Screen Daily (online) .Available at: https://www.screendaily.com/features/shooting-the-outrun-in-orkney-nora-fingscheidt-on-unpredictable-weather-and-scottish-hospitality/5196241.article

[3] Mireia Mullor (2024) ‘The Outrun review: Saoirse Ronan is a force of nature in poetic addiction drama’ in Digital Spy (online) [24 September 2024] Available at: https://www.digitalspy.com/movies/a62328358/the-outrun-review/

[4] Aoife Daly (2024) ‘Saoirse Ronan realises childhood dream as Scotland becomes ‘second home’ after secret wedding in Edinburgh’ in The Irish Independent (Sat 21 Sep 2024 at 02:30) available at: https://m.independent.ie/style/celebrity/saoirse-ronan-realises-childhood-dream-as-scotland-becomes-second-home-after-secret-wedding-in-edinburgh/a107669324.html

[5] Emily Zemler (2024) ‘Why Saoirse Ronan’s time has come’ in The Los Angeles Times (Sept. 25 2024 3 am PT) Available at: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/movies/story/2024-09-25/saoirse-ronan-the-outrun-blitz-interview#:~:text=Saoirse%20Ronan,%20already%20a%20four-time%20Oscar%20nominee%20at%2030,%20crashes