‘Here is a wasteland / of past aesthetics’[1]: In a poem that so insistently compare its mission to that of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, and it methodologies of building up the present from the fragments of ‘past aesthetics’, the supposition of ‘a deity in me’ may well imply how models of yearning in patriarchal culture for a Fisher King ignore the possibility of sustainable organic growth in the earth or anything else that is not subservient to the male principle of a highly controlled and regulated world. This is a blog on Rachael Allen (2024) God Complex London, Faber & Faber.

It ought to surprise me that you have to look for reviews of even poets who have already had a feted debut as Rachael Allen has with Kingdomland in 2019, in British online magazines only and from blogs from the United States. It no longer does. At least however that ensures a fresh take on the poet with less hackneyed expectations of poetry. Elliot Mason in The London Magazine, for instance, gives us this refreshing take:

Allen is writing a communist epic, a continuous hymn for revolution. For Allen, breakups and femicides are equally sites where oppression and misogyny operate, producing the classed and gendered experience of loss. In God Complex, that loss is brought together as a cyborg army, composed of the brutalised remnants of river fish, forest fevers, penniless tenants, feminised poets, and the environment itself. The message to those who claim the omnipotence of God is clear: beware the spectre of Allen’s poetry.[2]

Mason is billed in this article as ‘ a communist researcher and organizer’ and well aware of the reference in Marx and Engels’ The Communist Manifesto to the ‘spectre that haunts Europe’, but I do not see that as invalidating the committed reading he gives, comparing this work to Kingdomland, where the central focus is a working-class female cleaner of male offices, servants definitely of a gendered authority such as is a Kingdom, even as in Britain until recently, it was ‘ruled’ by a Queen. The poem after all is a deep act of revenge against a man, and the systems that make women and the ecological systems of the earth prepared for subservience to a man (whether father, husband, lover or God – perhaps even King) for his controlling violence and claim to own the world as his set of commodifiable resources. Such systems are regulated by capitalism after all, which Mason sees triumphing in the fact that it is felt so viscerally like oral rape by the narrator at ‘the edges of my teeth’ as they ‘bleed and taste / metal in my mouth, like a big iron dick’.[3] It is important to see here that though she gags on that imagined ‘dick’, it is imagined from the taste of iron in her own blood: the patriarchal submission learned to the rule of capitalist patriarchy, as I suppose Mason might say. Thomas Higgins does not invoke revolution in the poem in his reading, expressly himself soberly thus:

Allen’s poetry is preoccupied with the parallels between interpersonal and environmental abuses. If people can treat their loved ones with such disdain, how can we hope to repair our broken societies or heal our ravaged planet? While Allen wisely avoids grandstanding, her poems offer new ways of looking, both at ourselves and at the world we inhabit, ….

To not ‘grandstand’ is not to offer the big (or grand’) narratives of feminism and socialism (Mason’s specialty as a political thinker is the work of Judith Butler) in a poem as a solution, but rather a new awareness that queries everything, including, as Higgins goes on to say, ‘the role of poetry in such dire times’. Higgins lists Allen’s targets thus: ‘girlhood, late-capitalism, climate collapse, and the grotesque lurking just beneath the surface of domestic life’.[4]

Higgins cites this self-examination of text of itself:

What’s the point of all this text? I still have to live without you. I watch people who block the ants’ nests’ swirl outside their homes. What kind of god complex is this? Let them live; let them maul the house and surfaces with black trail. Deify them and their paths.[5]

Where the principle of masculine regulated control – home-ownership for example – sees ants as a nuisance, Allen finds her gods in them and their ‘paths’. Regulators are ‘people who block’, on social media or their android phones no less than the ant-holes of creatures with no intent of malice – black only because they are black, not because humans have constructed this adjective as if it had an intentionally negative or secondary meaning to ‘white’, such as it has in Shakespeare’s Othello (see my blog on this issue at this link). The ‘god complex’ is a version of the Oedipus complex – it all hangs on the gender and right to control of the entrained masculine, even exercised by a woman (as it sometimes is).

Reading this book of poems with an awareness of one’s responses good and bad is instructive. Sometimes I felt I did not want to read another heterosexual love poem, or set of poems. about the loss of a man ever again. I felt it hackneyed! But I felt this momentarily; only to find the volume beat me to it by both predicting and validating that reaction as the lyric voice has the same reaction to itself. The female poet is deeply entrained to love poetry, Allen implies, that pollutes her, and the flow of her blood in her veins, as capitalist industry pollutes the waterways and blocks or slows up the flow of natural rivers, and she must rise out of it:

Never to have written a poem about falling in love, which is much the same as moving through a sticky spring stream, the banks of which are made from oil or phosphorous substance: being uncontaminated is impossible. These obsessions with interface reach back in time, which is to say, the form of the past pollutes a future terrain. There is blood in my carcinogens, like alphabet soup,[6]

I started by proposing that Allen’s lyricist uses reference to this male principle not only to understand the husband that discards her and who she learns to see for what he is but also to patriarchal capitalism and the service of that by ‘past aesthetics / patched up with modern tubes’; the inheritance of all poetry from the modernism of T.S. Eliot. After all a river runs through The Waste Land, in its setting on the Thames, its imagery and its flow as verse, and it sees redemption in a male principle – if not yet God and Christ in The Waste Land, although indubitably so by The Four Quartets, in past mythological traditions like that of the Fisher King, whom Eliot writes about in his reference to Jessie L. Weston in his notes to his poem. And rivers are rightly noticed by Higgins, who also points out usefully, that:

In January 2024, a water testing project conducted by British citizen-scientists found 83% of the UK’s rivers contain evidence of high pollution. This followed an Observer investigation from August 2023 that showed 90% of England’s freshwater habitats were blighted by agricultural runoff and raw sewage. Such environmental devastation undoubtedly forms a backdrop for Cornwall-native Rachael Allen’s God Complex (Faber, 2024), an impressive work that reckons with the consequences of human violence both on the environment and on other humans, especially those whom we claim to love.

Many rivers run through this collection, streams which guide the speaker’s journey through the end of an abusive relationship toward the uncertainty of life on the other side. Early in the collection, which reads as an interconnected narrative sequence of mostly untitled prose and lyric poems, Allen’s speaker reflects on the damaged nature of the man she loved: “I came across you / so deep in sadness,” she writes, “a sadness that churned / like a river bottom.” Accustomed to his moods, she diminishes and blames herself to console his incurable sorrow and self-hatred. The speaker loses sight of her identity, carrying the weight of his emotional burden beyond even their breakup: “Immediately after you left, I swam in the toxic river.” Having come out of a toxic relationship, the speaker enters another poisoned environment, “thick with hard-scummed edges, / feverish from farm waste and floating cut grass.” [7]

But perhaps what Higgins misses is the lyricist’s admission that she, and perhaps other poets like Eliot, who urges with Edmund Spenser ‘Sweet Thames’ to ‘run softly till I end my song’, rather give agency to rivers, which are invariably metaphors for the flow of time and duration, that they do not have to exculpate poets from political responsibility.[8] Another issue arises here for Epithalamion, as Eliot exploited it, is a poem about a good marriage governed by a man, as Eliot’s poem is so often about a bad marriage (to his first wife Vivienne Haigh-Wood) where the man has lost control of a woman presented as mad.

I think we are in rats’ alley

Where the dead men lost their bones.

‘What is that noise?’

The wind under the door.

‘What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?’

Nothing again nothing.

‘Do

‘You know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember

‘Nothing?’

I remember

Those are pearls that were his eyes.

‘Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?’ [9]

In contrast to both God Complex is about a woman at the rough end of a bad marriage with a controlling man, which, whatever else they were, is a true description of Edmund Spenser AND T.S. Eliot. Allen rejects their political affiliation with the current powers that were (Spenser to an Imperialist Elizabeth I and Eliot to The Tory Party at prayer, The Church of England). Allen has a different take on the flow of rivers entirely. It is she who ends up in the water not drowned men.

I give the water too much agency. The river doesn’t care to take anyone anywhere; it is fated to move. I was just existing in its movement.[10]

And this applies to ‘History’ too, another thing poets can sometimes fail to take responsibility for, especially for the worst as aspects of human agency it, such as war, poverty, substance abuse, domestic abuse and violence based on inequalities, oppression in the factory system, extermination of species of flora and fauna, the release of new pathogen viruses caused by ecological imbalance, like COVID, and pollution of land, air, and water, and, of course, the heartless production of foie gras as a luxury.[11]

Allen examines even the failure of her poetry, on its own, to address the feminist (the ‘history of women’s stories’) and class concerns that motivate her (even suggesting in the process a revised Marxist view of history);

In living I wanted to disrupt the history of women’s stories in my life, but it turned out I couldn’t. History is a sequence of repeating patterns so extreme they are inescapable: I watch the way previous histories are now travelled in. They are nefarious pre-fact; they’re writ:[12]

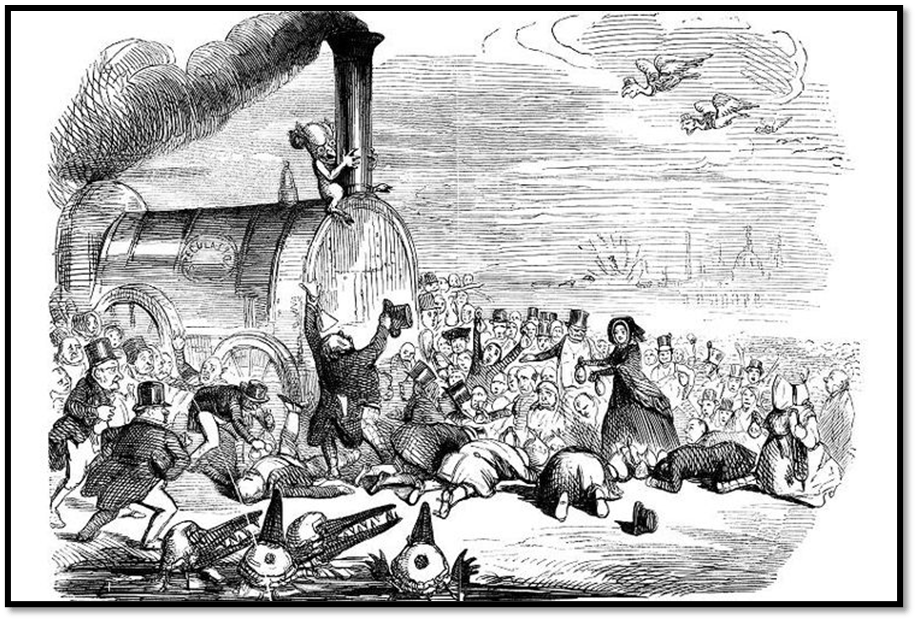

Later we get: ‘History clunks on, with us clinging to its sides’, where History is an industrial Juggernaut, an image as old as even liberal critique of capitalism.[13]

Punch pictures and satirises the ‘Railway Juggernaut of 1845’ : killing even the small capital investors who worship it.

History is full of male ruses, like New Green Deals, and they fool us that this improves on things and yet the poem asks, ‘can we survive this greenly’.[14] And the marriage the lyricist sees end was always soiled though she was not aware of it – like the house they lived in overlooking ‘the bloodbath soil of a racecourse’ where machine economics (‘machinc synchronicity’) take over the horses’ ability to function organically and there is ‘blood in the lungs of the racehorse’.[15]

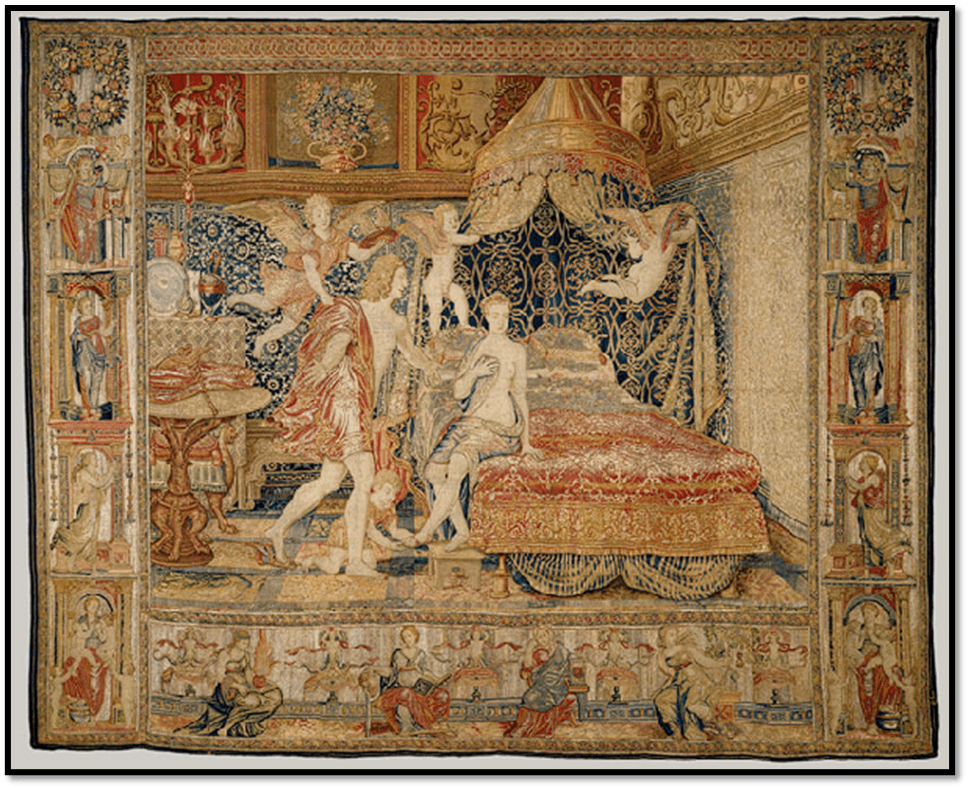

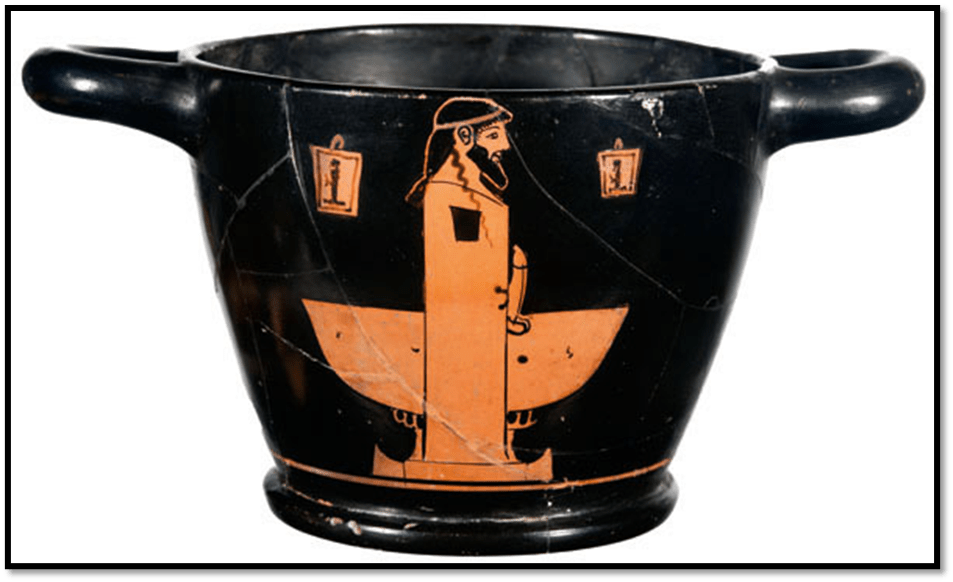

In a bad marriage a man encourages the introjected ideology learned from her father by each girl in girlhood that she ‘saw [him] divinely’, as the God of a hearth – a phallic Herm as erect as those of Attic Greek households.

She learns that, addressed to him; ‘Sorry was the language I learned’. She sees him always in a landscape where ‘you loom larger’. Even his mother apologises for him and his capacity to punish errant women by having their ‘hand pressed to a red-hot grate’.[16] The only revenge is to dram of violence in return: ‘and drive and drive / my thumbs into your eyes’.[17] He is no more a deity than the ‘Small Christ in shit’ she later imagines him as.[18] He is no Fisher King either. He exposes her to floods, to alcoholic drink and ‘renal failure’.[19] If he is a domestic God, she is the God spelled backward: a Dog.

In a hair shirt crawling through a vast and febrile state, I was learning what it meant to be subservient to someone, miraculous, the dog.

That is a phrase only men usually sentimentalise, preferring the loyalty to themselves of one, whilst meaning something entirely different by calling a woman a ‘dog’. But it is with the reform of poetry to that suited to the voice of independent women I want to stay, reading this volume still as in part an attack on the effect of T.S. Eliot. The poem of greatest attack – on the patriarchal generally is that which compares the way a stream disperses and accosts the eggs of a woman with the way ‘a man approaches, / or how a hand slaps water, or skin, / in play, or not play’.[20] Of course she wonders about this: ‘How should I know? What do I care?’ But care she must, it is woman’s only security. And not only women. In my opening collage I quoted those lines wherein the lyricist speaks of needing ‘metaphor’. It is a moment of desperation, as the ‘starving’ woman seeks nutrients but of the worst most toxic kind – sugar, the sweetness men associate with a good woman or Spenser of the Thames.

But metaphor grows in this volume to be much more than ‘sugar’, it grows to be a means of imagining freedom. Not all of this is clear sailing. Moments I still find difficult in the poem are those which valorise the sense of smell (and taste sometimes) over that of hearing or sight (the usual recourse of male poetry) because smell detects corruption better, as in the powerful poem, ‘Sense slides into oblivion’.[21] The one (of many powerful ones like the above) I had most problems with in this respect was this, which uses a very problematic simile for me;

Now I live closer to the soil and its mineral bitterness, plugged into its data, and haunt like anyone haunts day to day. I begin to smell compromised, like a worker. ….[22]

This intrigues and trouble. Here ‘smell’ is both an active and passive word. It is about the training of her own sense of smell in the dire strait of a bitter end to a marriage but also about her consciousness of being ‘smelly’ to others. And, here’s the problem for me, why ‘like a worker’, as if a worker joined a list of (supposedly) negative things as the ‘frog’ is, in this proem (prose-poem), thought negative. My own feeling is that this volume is so honest, this moment captures that time when the lyricist still makes value judgements that valorize the high and mighty (those ‘who inhabit the area’ or ‘belong’) over the lowly, little and marginal, amongst whom the ‘worker’ sits at this moment, unlike the woman protected and kept by a richer husband. After all in a poem I consider symptomatic of consciousness change (‘I know a skeletal brook’), the ‘frog, fish or toad’ are emitters of the valid – the eggs of the female. But I leave that to your judgement. I note that Higgins does like me, I think, see this as a volume of poems about consciousness raised in the process of loss. Here is what he says:

In the book’s second section, Allen’s speaker post-breakup begins to actively interrogate her relationship to a damaged world:

The rural military base on the edge

of the beach near the shoreside

firing range. In it, red alert sounds

in the fake suburbs built

to practice catching terroristsAllen’s concise lyricism offers striking moments of juxtaposition, highlighting the fine line between sanctioned and unsanctioned spaces of violence. These lyric fragments work well alongside the collection’s more reflective prose poems, which often read like notes for unfinished essays or hastily drafted diary entries: “The hormones I take live in the water around me and alter the water and me.” Again, the speaker considers herself in relation to her surroundings, her chemical makeup inseparable from that of the river.

The leap Higgins does not take is the one that Mason does: the latter imagines the lyricist (or the poet at least) as a political activist finally, learning the fallacies of the society that sees its enemies always as ‘terrorists’. In the end, the enemy looms and approaches us: but we can fight back. Can’t we?

The dark offshore rigs – big skeletons – look

as though they’re striding slowly

towards us, towards land.

This is an amazing collection. I love it. I recommend it. This Forward Prize judgement is going to be difficult.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Rachael Allen (2024: 1) God Complex London, Faber & Faber.

[2] Elliot C. Mason (2024) ’Rachael Allen’s God Complex’ in The London Magazine (online) Available at: https://thelondonmagazine.org/review-rachael-allens-god-complex-by-elliot-c-mason/

[3] Allen op.cit: 31

[4] Thomas Higgins (2024) ‘A Review of Rachael Allen’s God Complex’ in The Adroit Journal (online) Available at: https://theadroitjournal.org/2024/05/06/a-review-of-rachel-allens-god-complex/

[5] Allen: op.cit: 89

[6] Ibid: 85

[7] Higgins, op. cit: the poems referenced are not sourced but the last two can be found in Allen, op.cit: 7f.

[8] See the section headed ‘Adaptations’ in: Prothalamion – Wikipedia, available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prothalamion#.

[9] From T.S, Eliot The Waste Land, available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47311/the-waste-land

[10] Allen, op. cit; 8

[11] For examples (sometimes as metaphors) see ibid: 7, 13, 14, 27, 31, 36, 39, 41, 64, 69, 79, 83 (foie gras) 89, 90, 92, 99

[12] Ibid: 25

[13] Ibid: 61

[14] See ibid: 27 & 78 respectively.

[15] Ibid: 10

[16] Ibid: 13 – 14

[17] Ibid: 36

[18] Ibid: 87

[19] Ibid: 22, 56

[20] Ibid: 79

[21] Ibid: 69

[22] Ibid: 52

2 thoughts on “Here is a wasteland / of past aesthetics’. This is a blog on Rachael Allen (2024) ‘God Complex’.”