Tony Cragg once said, as cited in the catalogue for the exhibition of Cragg’s sculptural work and his co-curation of that exhibition, in the house and gardens of Castle Howard that the ‘disquieting flux and flow of [his] sculptures express a state of mind or a mental picture … I am interested in expressing thoughts as topographies’.[1] Jon Wood thinks that there is a stern contrast between Cragg’s sculptural forms and the art and architecture of Castle Howard like that between, on the one hand, ‘curved biometric’ structures and ‘the building’s orthogonal symmetries’, and, on the other, ‘bold colour, polish and translucency’ to the ‘natural palette of cut stone blocks’.[2] I think, though I take his point, that Wood may miss the aesthetic effect, not of Cragg but of Castle Howard itself in that comparison, for it is a structure of interior and exterior space that, once we attempt to internalise its effect and affect together, as one whole achievement over a long time period in making, also totters on the edge of disquiet.

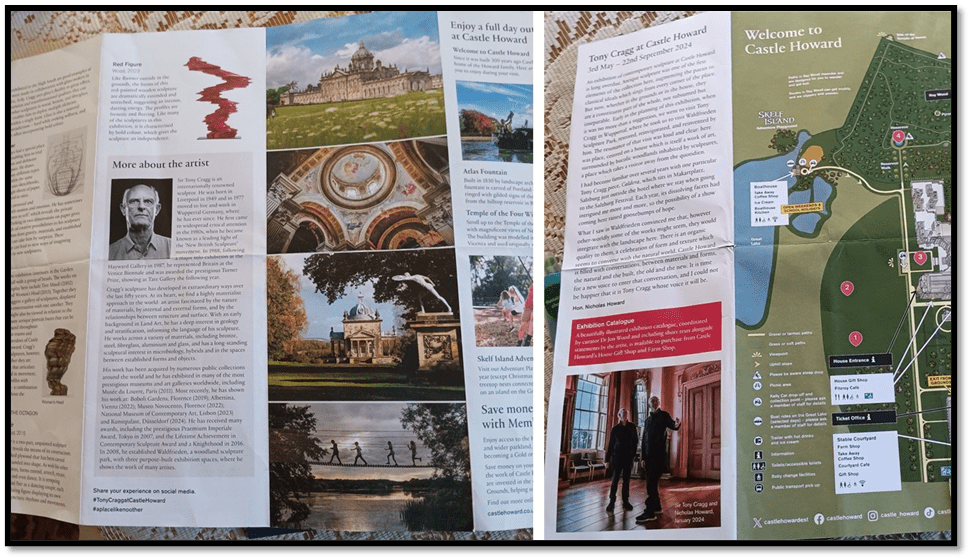

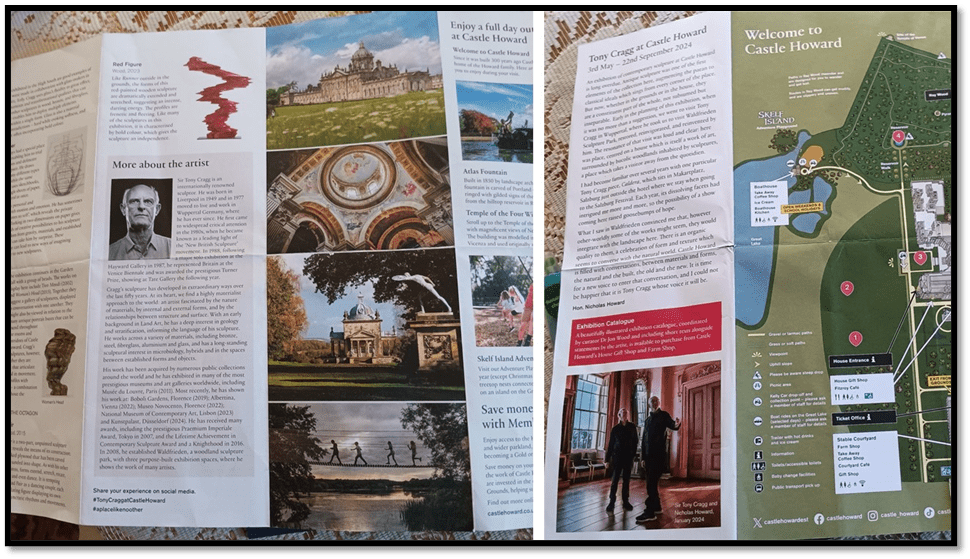

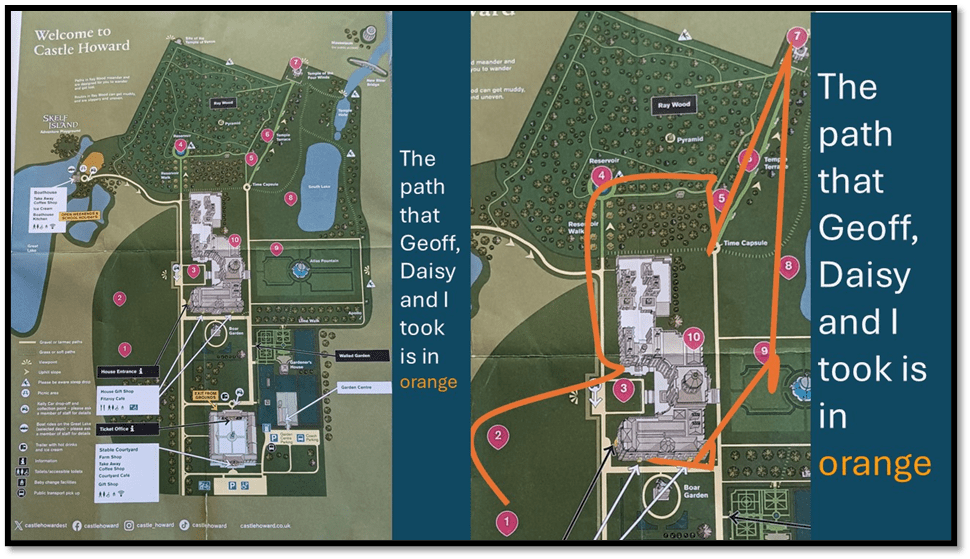

The leaflet used at our trip to Castle Howard. The map made it possible.

I have to start with querying some words by Jon Wood in the fine catalogue (worth buying in its own right – ISBN 978-1-3999-8354-9) not because I am either an art historian, or truth to tell, a true scholar anymore, with an ‘axe to grind’. After retiring, I write blogs, seen by few and read by less, to keep my own mind active and most where I try to orientate myself to art that has opened up new avenues of thought, feeling and sensation for me. I do not so much disagree with Jon as want to be able to articulate just a bit more precisely the effect generated on me by some experience and in this case, I found Jon Wood’s contrast of a venue for art to be seen with the art itself a useful start for helping me comes to terms with my own feelings and much more random thoughts than Jon Wood’s.

The catalogue edited by Jon Wood. The pictures in it are excellent. It helps with the art.

I have seen Tony Cragg’s work in an earlier exhibition – a retrospective at Yorkshire Sculpture Park – and so a chance to catch up with his latest work was appealing, especially since Geoff, my husband, and me had booked a couple of nights stay in York with the intention of going to the PBFA (Provincial Booksellers Fair Association) far there. To return home via Castle Howard seem a plan, extending the holiday and the advent of a bit of sun in the weather. Besides Castle Howard is dog-friendly, so Daisy could come to, even if it meant we had to visit the house separately.

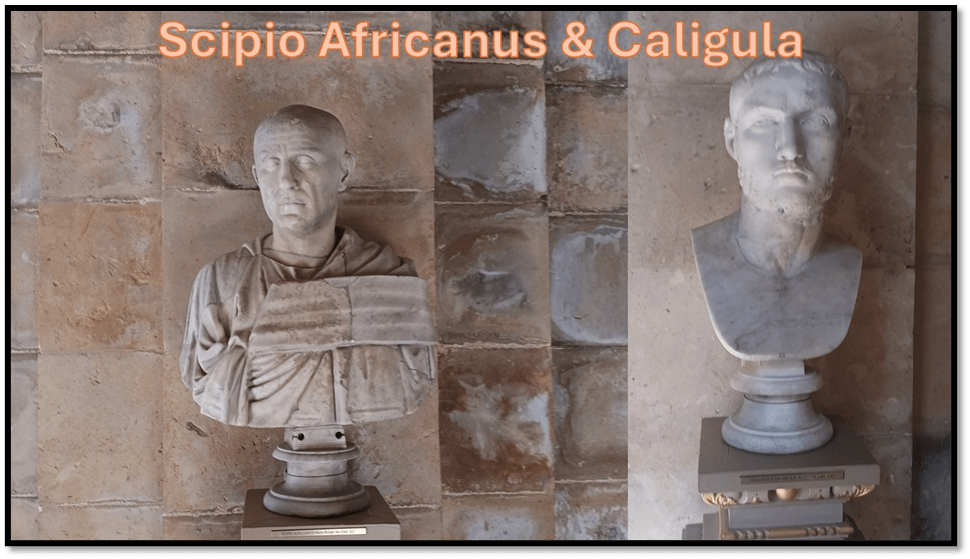

Jon Wood, in his essay, likes comparisons, especially those that speak of the venue chosen to display Cragg’s new art. He refers us, for instance to the Roman portrait busts, with their intense psychological realism, even if in the aid of the mythologies serving Emperors and generals of the Roman Empire, but only in order to contrast them with Tony Cragg’s work. Classical portrait busts decorate the galleries of Castle Howard.

I wanted to focus on Cragg but myth serves its purpose to draw me whilst in the passageway above to identify strange psychological types – whether infamous generals or feral emperors, such as. Respectively, Scipio Africanus and the Emperor Caligula.

Wood says that such examples ‘displayed in conversation with each other’ show that what Cragg is doing is something different, are not even like ‘classical portrait busts’ but:

imaginary configurations that articulate the idea of head and mind in movement. They exchange likeness and celebrity for powerful coalitions of transformation and stasis, flux and form: sculptural renditions of developing psychological states and fast-changing points of view.[3]

This leads him into the comparison of the whole house that is Castle Howard with the sculptures I cite in my title. Here it is all again! We need to start with the artist’s own authority for basin view of his art on the interaction of person, body and mind. He is cited in the catalogue for the exhibition as saying: ‘The disquieting flux and flow of the sculptures express a state of mind or a mental picture … I am interested in expressing thoughts as topographies’.[4] We will need to return to the term topography – which refers to representations pf ‘place’ (from the Greek τόπος (topos, “place”) and -γραφία (-graphia, “writing”).

Wood thinks that there is a stern contrast between Cragg’s sculptural forms and the art and architecture of Castle Howard like that between, on the one hand, ‘curved biometric’ structures and ‘the building’s orthogonal symmetries’, and, on the other, ‘bold colour, polish and translucency’ to the ‘natural palette of cut stone blocks’.[5] I think, though I take his point, that Wood may miss the aesthetic effect, not of Cragg but of Castle Howard itself in that comparison, for it is a structure of interior and exterior space that, once we attempt to internalise its effect and affect together, as one whole achievement over a long time period in making, also totters on the edge of disquiet.

What do I mean by this? In the Castle Howard history of the building online we read the following summary:

The 3rd Earl of Carlisle enlisted the help of his friend, dramatist John Vanbrugh. Vanbrugh, having never built anything before, recruited Nicholas Hawksmoor to assist him in the practical side of design and construction and between 1699 and 1702 the design evolved.

Built from east to west, the house took shape in just under ten years. By 1725, when an engraving of the house appeared in Vitruvius Britannicus (The British Architect), most of the exterior structure was complete and its interiors opulently finished.

However, at the time of Vanbrugh’s death in 1726 the house was incomplete; it lacked a west wing as attention had turned to landscaping the gardens. …. [C]ompleted by Carlisle’s son-in-law Sir Thomas Robinson, Vanbrugh’s flamboyant baroque design would be brought back down to earth by the 4th Earl’s conservative Palladian wing.

From the outside, the unbalanced appearance of the house provoked a mixed response, and many visitors noticed the disjointedness.[6]

The story there more nearly matches my responses to the house than Wood’s reference to ‘‘the building’s orthogonal symmetries’, for my feeling was of a place more compacted by asymmetries – lacking balance in more than one sense of the word, for though the house often refers to classical symmetries and their resurrection in Palladian architecture. As the website summary tells us the origin of the house was in the fantasies of a Baroque architect, who also designed Blenheim Palace, who was also a dramatist. Its classical was often mixed with Baroque fantasy, ‘exuberantly decorated in Baroque style, with coronets, cherubs, urns and cyphers’, in Wikipedia’s words.

The mix of styles in the collected decorative artefacts, the comedy mask to the left of the staircase in collage top-left, is a ribald joke. There is something even of afterthought over-compactness in the domed atrium with his high Romanesque arches and concealed staircases with exciting vistas. This isn’t the idea of a consistent classical response despite the early intention of symmetry by Vanbrugh. The 3rd Earl of Carlisle was a Grand Tourist – like many eighteenth century dilletante’s known for their style and flamboyance, with the rather vulgar fantasy edge of the Kit-Kat Club which boasted both Lord Howard and Vanbrugh as members. Collection and taste were not in the eighteenth century things associated with an austere aesthetic, collections tended to be idiosyncratic in the selection of items and their display where plenitude (or even perhaps a cluttering of ’statues, busts, urns, bas-reliefs, bronzes, marble columns and mosaic tops’) might be the dominant effect.

The Chief curator of Castle Howard writes in the catalogue about how, under Vanbrugh (and his assistant at this early time of his adventures in architecture, Nicholas Hawksmoor – another lover nevertheless of dramatic effect) ‘sculpture and architecture were so closely intertwined that it was hard to tell where one began and the other ended’.[7] Similarly he speaks of the grounds as being ‘filled with sculpture’ a terminology that does not shout out for the effect of ‘taste’ (not that I like that abominable concept).. Henry Howard, the 4th Earl of Carlisle too was a Grand Tourist and Ridgway says that under his curation of the estate there ‘was a real danger of Castle Howard becoming a jumbled storeroom instead of an ordered display space for these treasures’.[8]

In fact Ridgway possibly holds back from saying that, to an extent, his is still an effect of visiting this estate. It was certainly mine, though I like the idea of clutter much more than that of regulated ‘display space’. And I think we get it wrong to see the over-crowding of this house as an accident of history, for the idea of ‘clutter’ is almost a principal of both display and aesthetics in Baroque and Rococo art. Extravagance is seen as a richness not a sign of disordered taste, though it has that effect on some of us who claim to have ‘taste’. I felt more comfortable about this after I had got to the end of my house tour (while Geoff cared for Daisy in the lawn of the house’s café). That, for two reasons.

First the chapel – a cluttered mess to some and ideal to show the disordered Catholicism of the Brideshead family in the film of Brideshead Revisited). There are fine things here but they feel fake and over-the-top, if delightfully colourful. It is as if an idea of infinity where squeezed into a space that had permanently distorted it. But I love it – its utter campness that pretends nevertheless to mimic the classical in Baroque fashion.

But more than this I was fascinated by the last room in the house where just as you leave via a kind of recreated Gothic spiral staircase, there hang some of the many capricci – often ‘Anglicised in the eighteenth century to the term ‘capriccios’. The ones I saw were mainly by Pannini, of whom, Wikipedia says: ‘Most of his works, especially those of ruins, have a fanciful and unreal embellishment characteristic of capriccio themes’. On leaving the room I noticed what I believe to be an eighteenth century mirror reflecting these back to me – capriciously one might say. The effect heightened the delight of the artifice that invented scenes of anachronistic architectural and other artifacts in cluttered arrangement so theatrically boast in themselves – ‘look how clever and cultured I am’.

It seems time though to sum all that up, for the effect of the artifice of the Baroque is deeply unsettling to notions of measurable time and space: anachronism becomes a means of unsettling our grasp of settled time and space, and great Baroque artists, even the ecclesiastical-serving artist-giants like Bernini were proud to do this. And this is how Castle Howard strikes me – outside and inside and in the unsettling cusp between interior and exterior, so important in Baroque architecture.

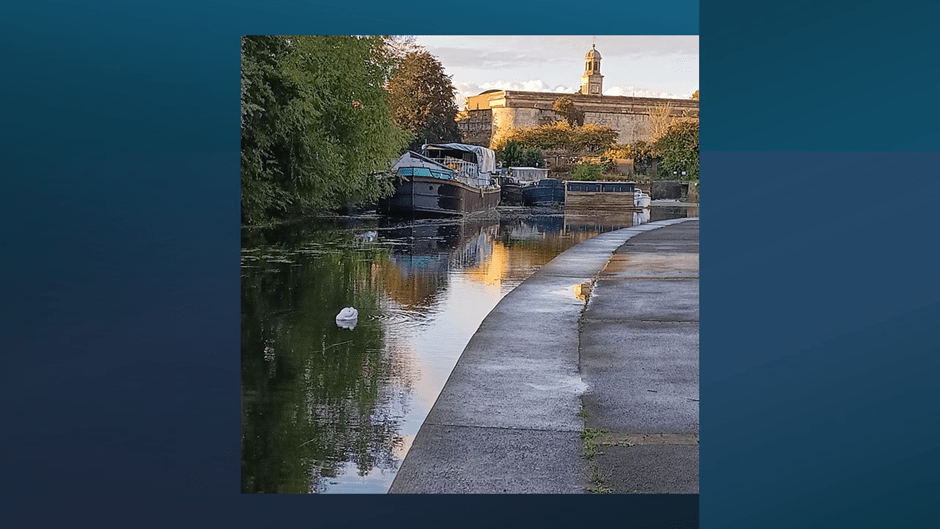

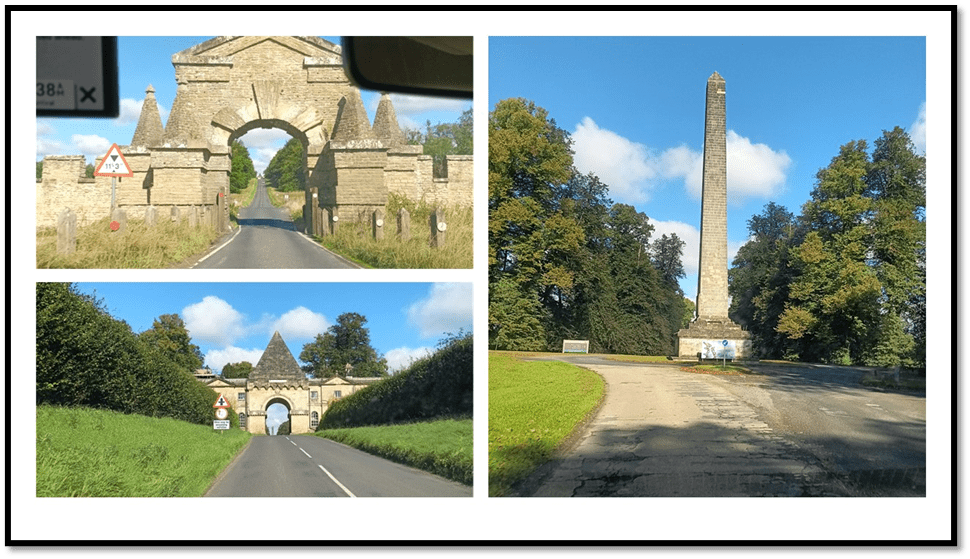

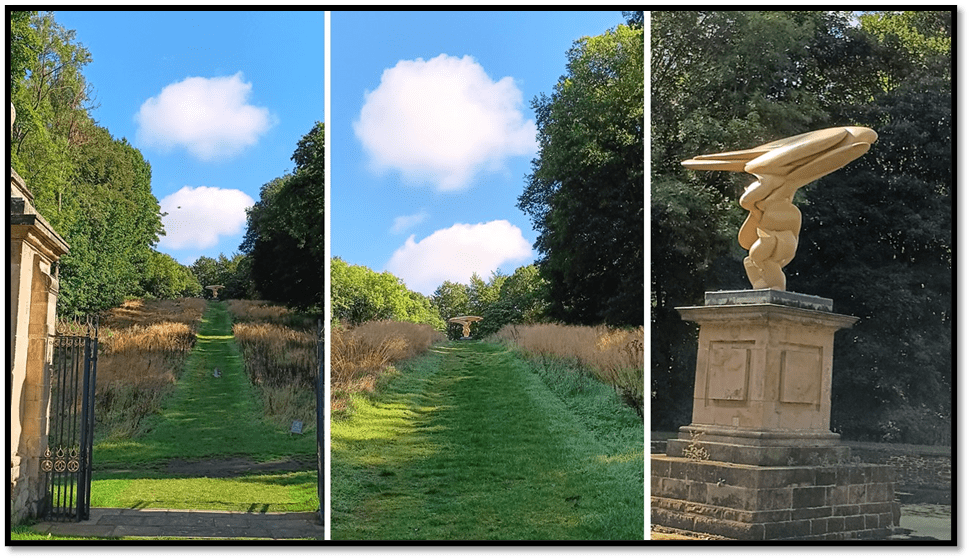

For if I think about even ur approach by car down a long avenue, exploiting the blinding effect of hills and artificial valleys and false boundaries, often no more than an isolated gate or ‘obelisk’, speaking of the architectural fancies of many historical periods and civilisations, you know you are entering someone’s the fantasy. The straight road you enter by once in the estate leads across the face of the building above one of the many entrained lakes offering ‘picturesque’ views up a hill to an entrained wilderness (of which the eighteenth-century was fond (an artificial wildness), of which more when we speak of Cragg’s Over the Earth (2015).

And then the house in the immediate setting, where even the planning of a wave-form declivity, like the levels of a rapids formation in a river but over which only the epiphenomena of light and shade flow, uses the shadows cast by huge trees to create the effect of some kind of unsettling illusion (in the collage below).

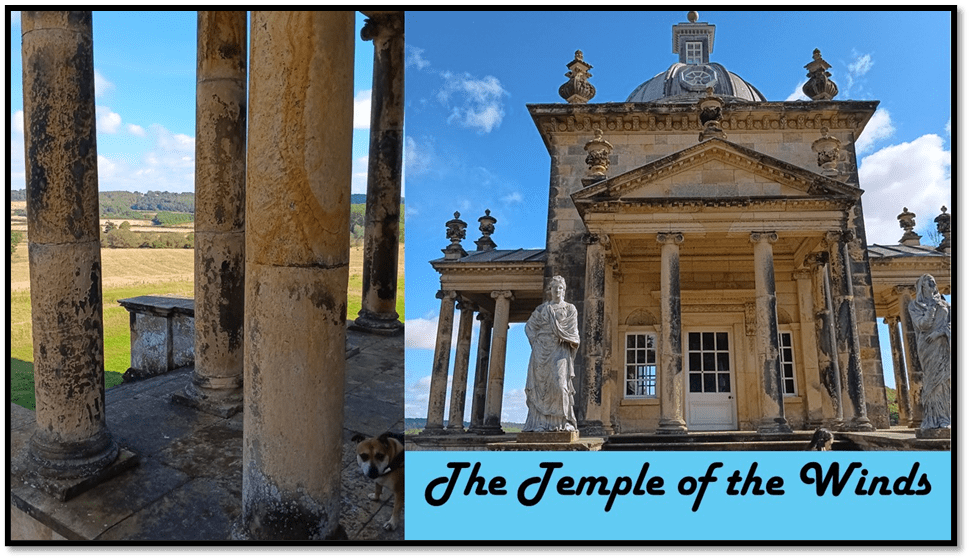

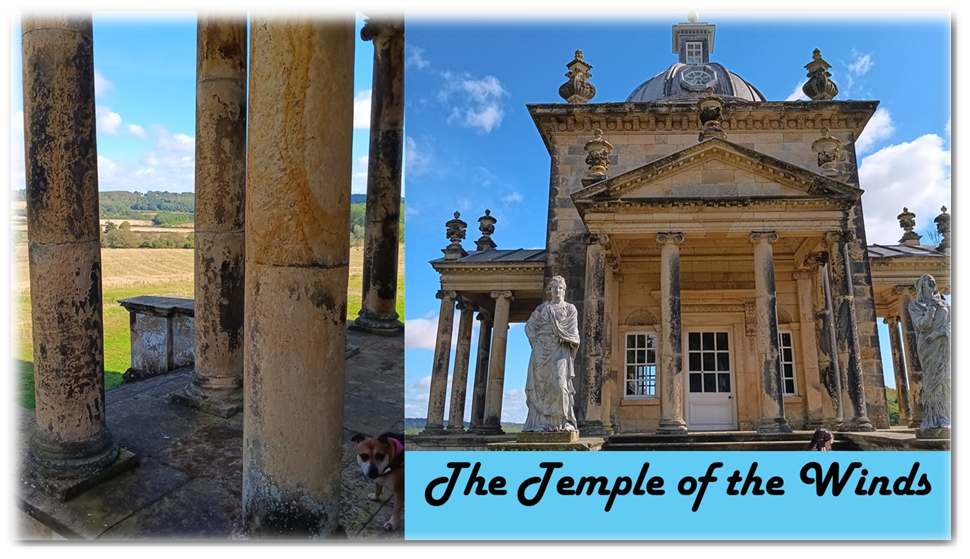

The aim is to create beauty by diversity of landform – wooded hills but not too high nor too rough – plains that seem to extend to infinity, huge water features that seem to interpret the whole world, like the atlas Fountain, where water shoots out of the globe supported by Atlas. And our sense of scale is thrown. A relatively small estate becomes to look as if it is immense, although sometimes immensity seems boxed up – the very idea that excited people about having a Temple of the Winds at your domestic estate’s near extremity, with a side for the wind’s from each quadrilateral measure of direction_ North, South, East and West. Again we will come back to that Temple (Daisy manages to insert herself in the collage below).

Small as the domestic bounds of the estate turn out to be we couldn’t have survived had not a kindly receptionist helped us to the last hard copy of the direction leaflet she could find.

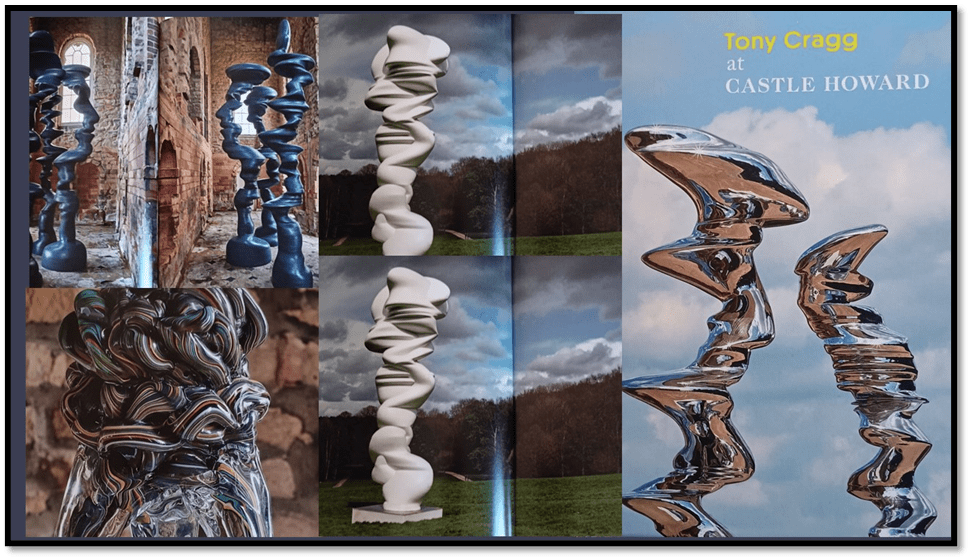

I bought a catalogue here too. Looking at it later, one of the benefits of that is that its excellent photographs show what some of the sculptures look like in different weather conditions – however for us the sun shone, clods herded but only as sheep do with large spaces between them and white in the light. The tangled interactions of his forms helped even looking briefly at the book to interpret for me, some of the unease I felt at this venue. Even the colours of the lass sculptures inside the house though were captured better in this book.

But for now, the leaflet was king, for it had a map and from this we routed ourselves, though Daisy seemed unsettled.

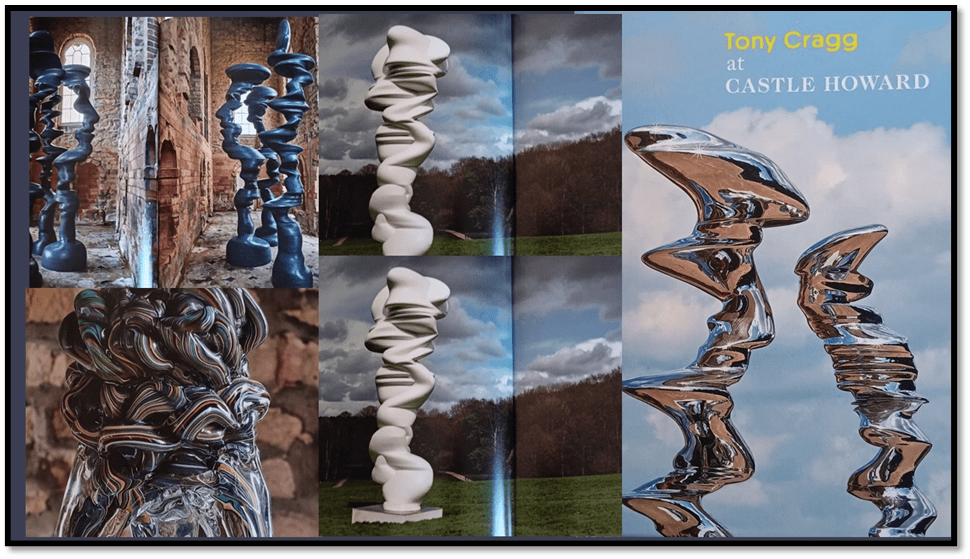

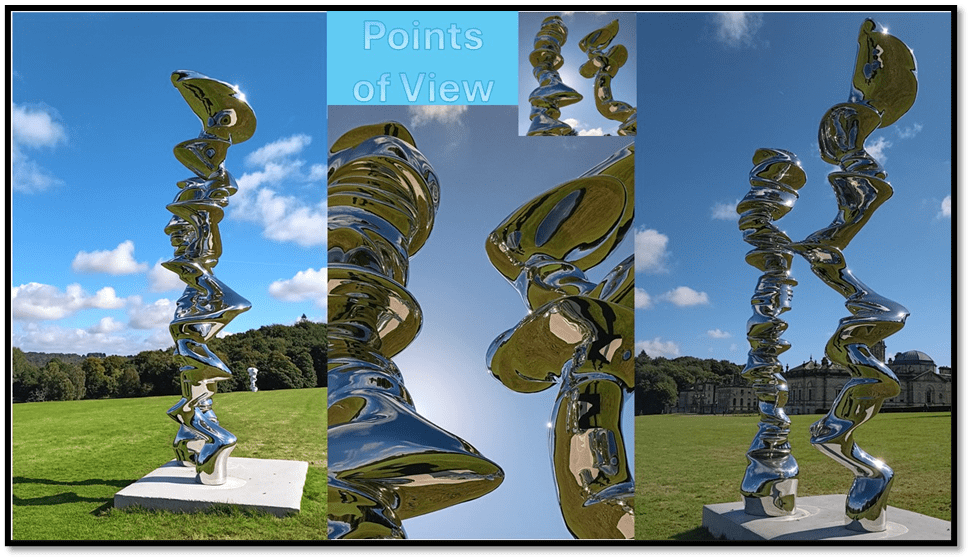

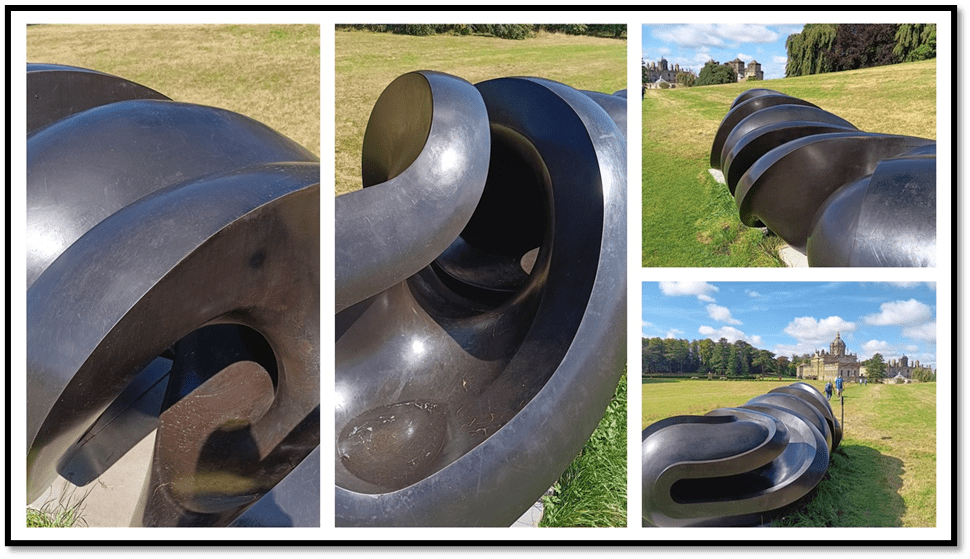

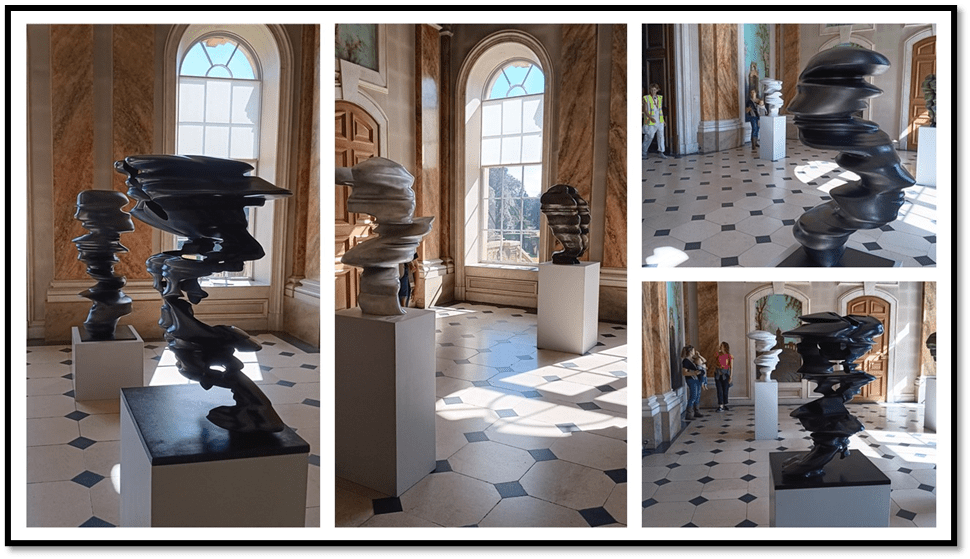

From here on, we tackled the forms that Cragg uses to illustrate so much about the relationship between modernity and deep time, isolation and interaction, and their interaction, including those moments in circling a biform sculpture, such as the magnificent Points of View looks as if it were truly uniform. It is usual to describe such forms as biomorphic but the intention of the metallic shine is to remind us of a kind of unsettle industrial modernity where time and space are in flux. It is appropriate with Cragg to see that any number of forms may become visible to us as we look – but particularly bodies (whole ones or partial) and faces in profile. Light and shadow animate the forms throughout, with surprising declivity such as those I had already seen near the house.

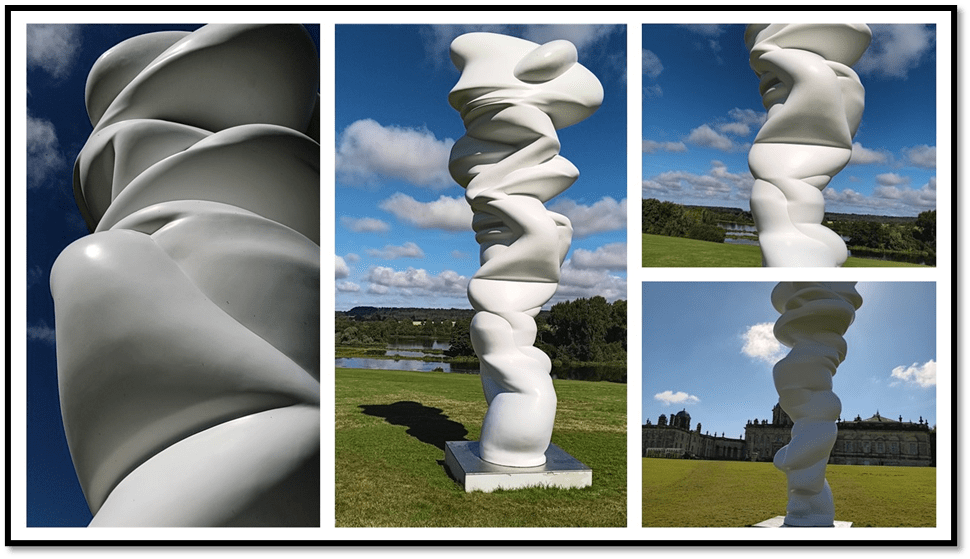

But reflective metals also hold you off, though you can and should touch Cragg sculptures that aren’t forbidden to you – it is part of their aesthetic wholeness. Hence to move from Points of View (1 on the map) to Senders (2) is a wonderful thing, for the fibreglass of this form can seen both soft and hard to sight. Is it an illusion that Senders is warmer to the touch than Points of View, even if the touch is an illusion of the gaze or haptic. It is touch though that seems to validate the illusion.

Both works of art illustrate Cragg’s interest in forms that seem to maintain their posture though seeming to be about to lose it – something he may have meant by saying: ‘I am interested in an imbalance of form struggling to maintain an equilibrium’.[9] In Senders the lack of balance has much to do with what appears to be badly distribute volumes and the weight we falsely attribute them.

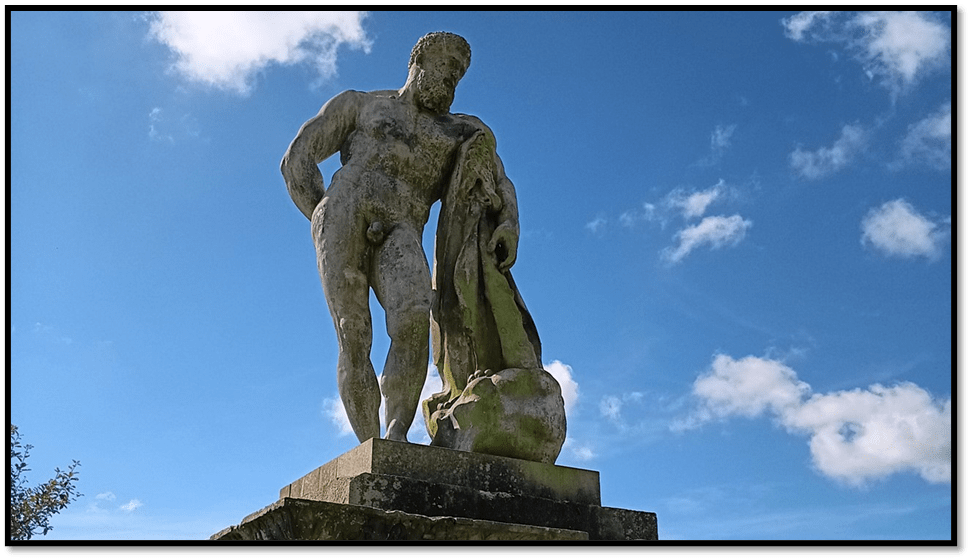

Senders defies us by still standing but not by standing still. To walk around it is to feel as if it were illustrating some inner dynamic of motion in itself, but Cragg knows this is a basic illusion of sculpture. It is just that classical sculpture defies our sense of that by insistence sometimes on frontality and ideal gazing point that matches that frontality. We do not, for instance, even feel tempted to circulate around the Hercules that we see on the garden pathway, wide and tree-lined that leads to The Temple of the Winds. Hercules leans to guide us to his frontal view.

That is not to say that posterior views don’t matter in such art but that they become secondary as part of their aesthetic. What is frontal and what posterior is of course a moot question in Cragg. Even though he is not a figurative artist in an obvious sense, he says that his sculptures are ‘at times organic and even figurative, while others are reminiscent of geological formations’. In my view they can be simultaneously both, or at least some of them can, especially Senders, and Masks (3), which we see next on our pre-planned comforting route.

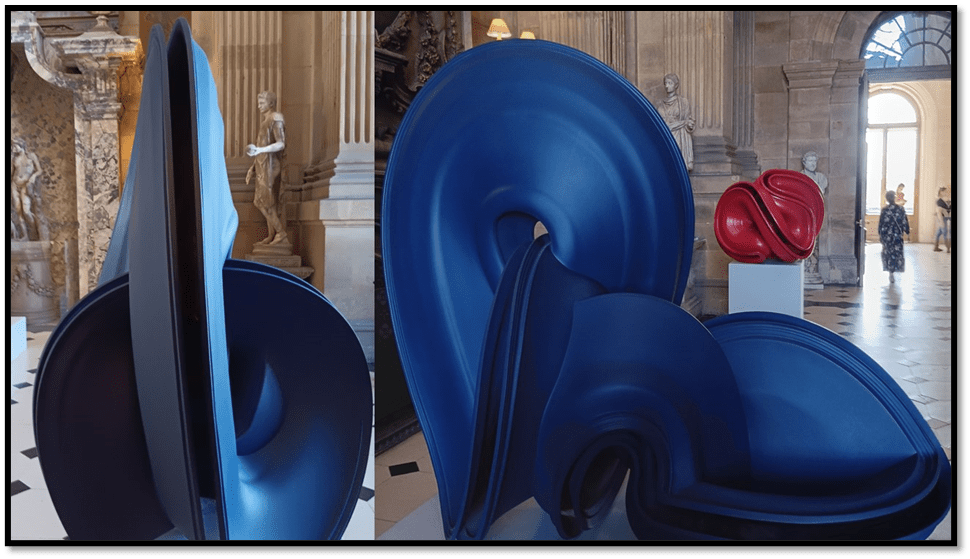

Masks is one of the works Wood relies upon in his contrast between the ‘classical’ symmetries of the house and gardens (or part of them at least) and Cragg. Even Cragg sees Masks as one form that keeps up an illusion of being the tense struggles between two similar forms, which he sees as faces driving into each other – in union or aggression or both. The forms are both biomorphic, psychological concepts and art genres. He says, it is ‘a blend of personalities, a sculpture and a bas relief all at the same time’. He talks about it ‘retaining its geometries’ whilst using the slippage between the inside and outside of things it implies as a concept that no geometry could explain or exp[lore. As we look at it and rotate around it, it seems to be seamed and / or layered at times but not at others: it is bulbous or it is aspiring to the thinness of material with a raised relief only. It intrigues.

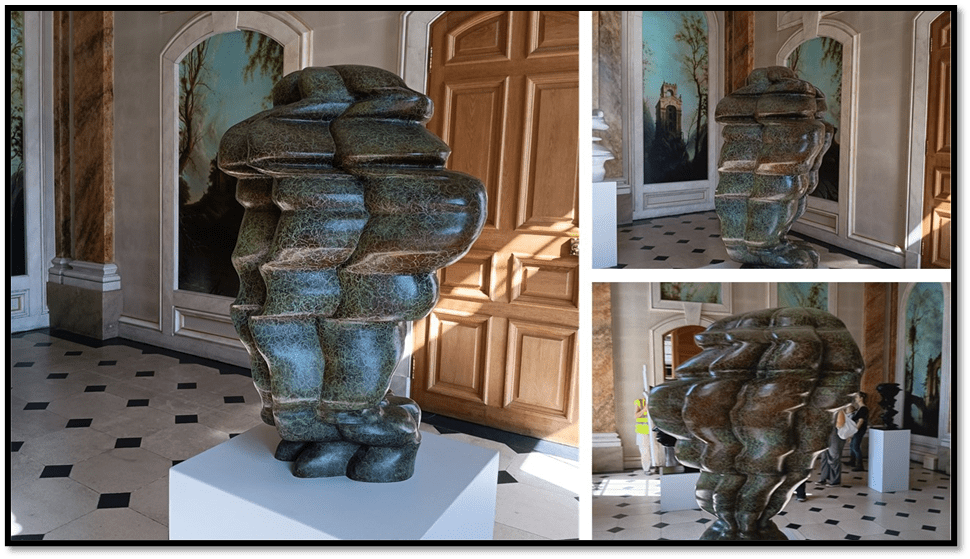

From there we head back to that long extension of the approach drive and look up to Over The Earth (4). From below, it looks like something monumental, yet we cannot see that it is stood on a plinth, in the manner of conventional sculpture, perhaps looking back to the obelisk at the other end of the drive within the domestic grounds, and contemplating its own iconic nature. In fact we will find the plinth it stands on is in the middle of a biologically alive artificial reservoir, Baroque to its stone heart.

Over the Earth stands as if an embodied animal, although its head is a relation of layered strata, with a pronounced and off-balanced curvature. Like Senders, it seems to want to topple, but this time from a height onto which it has been elevated without being asked if it wanted this, as we know Hercules wanted it in the example above. We had to rise up a grassy slope to see it and we may share a little of its fatigue as a result. But having got there we understand that its material (fibreglass) shares as much with the water it stands over, and is reflected in, as the regular geometry of the plinth. At times I see a kind of Narcissus in its posture.

I think I got entranced by the reflections (the photograph in the catalogue emphasises them) but I still prefer to think of that reflection on the water surface battling the pond weed and algae that might fragment the fair image it will never see. It is a conceptual piece that is precisely what makes it need to be topographical for Cragg. It is contemplating the space it is by virtue of its endless unstable action making into a place, a thing we have arrived at up the hill journey and will leave through the wood that surrounds it – a thing, as in all Baroque landscaping both natural and artificial – planned to be a wilderness. Beyond it is the work Versus (5).

Cragg tells us that it is a representation of the sun, but seen in the dynamic of the internal explosions, a kind of natural violence that is barely allowed to be conceived of as natural, that give it shape and form. The point of the identification for Cragg is to show us that there ‘is always an internal dynamic in things. It is very difficult to find static forms’.[10] This gets us near to understanding hoe Cragg’s work conceives of sculpture, which we think of as stilled motion. Its point though is to reanimate that motion that may militate against stasis – in fact must do so. To travel around Versus is to see how the impression of a rounded volume in the sun can be reduced, like Masks, to a kind of bas relief flatness. Yet as we approach to look nearer the colour , shape and interaction of light and shadow on the surface looks to move towards us.

The hill we go down is gentler as we join the path to The House of Winds. But before we get there we might wait to see Early Forms St, Gallen (1997) [6]].

How you see this work changes much in the conditions in which it is seen. The catalogue captures the length of the form better in its photographs than I try to do. The form veers between suggesting the biomorphic(a worm perhaps) and the industrial instrument from even early forms, like the Archimedes screw used in the Ancient Nile to get irrigation water. Even on this hot day, as you see centre in my collage above, puddles of water collect in the interior coils of the shape, that looks as though it ought to have an interior connecting passage. The shape invites you fo follow with your gaze into its grooves to find a hidden path. All you see is involution and layering, capturing the cusp of our concepts of inside and outside – which are hardly binary concepts in this form. Again hard and soft appearances coalesce as do images of a living thing resting and a ruthless mechanism driving on. I love this early piece. As you approach The Temple of the Winds (see it again below) its role as a site marking a boundary of something that is conceived of as without boundaries in the Baroque intentions of the grounds is clear. The motion of the air as winds ought to be uncontainable but here humans attempt to do so. It uses a natural eminence in the land to raise you higher on its external dais to see the last of the Baroque follies in the grounds – an Italian style bridge for instance, whilst accessing the flattened landscape, seemingly endless beyond that – the land that cemented the idea of aristocracy into English hearts.

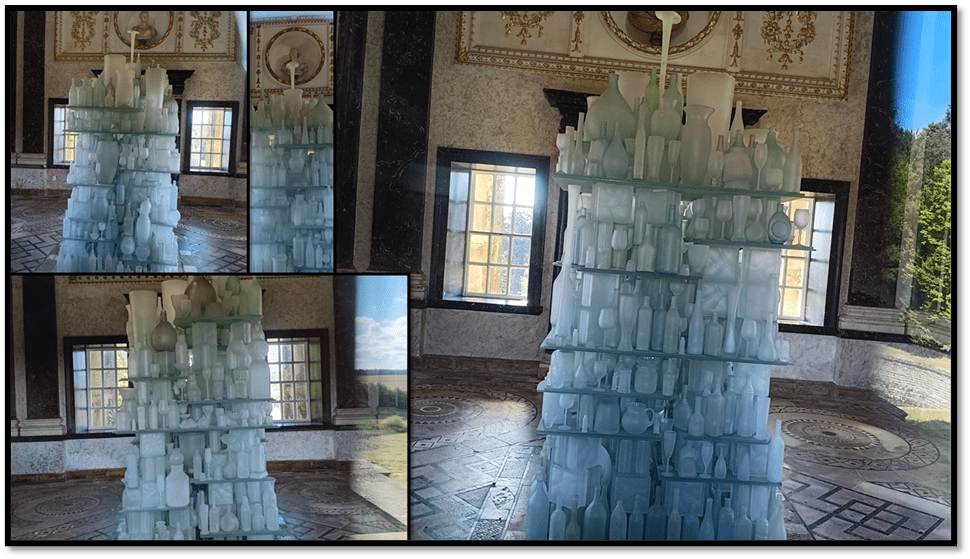

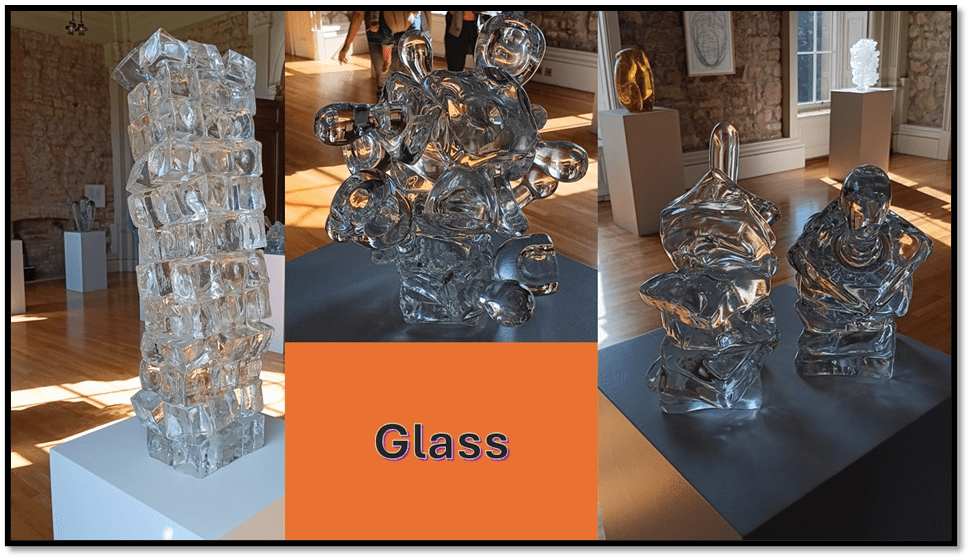

From the balustrade that runs around the temple we get views through the many windows into the interior of the ‘temple’, though the interior is closed to us, The work inside is called Eroded Landscape (7) – 1999. It is an early work in glass – we see more contemporary glass inside the building later – in the form of a tottering unstable tower, made of up layers upon which manufactured old glass forms stand – bottles, glasses, and crowned by a huge up-ended flute glass. The instability is enforced by the angle you take the structure from. The ‘professional’ photographs of the catalogue miss a feature of how this thing is seen, which you catch in my collage below.

Because it is seen through glass, only the photographer’s own shadow on the reflecting glass allows a clear vision. See how my photograph details are often then visually bounded by a strong reflection of the outside of the building, landscape and sky in the glass. The effect is almost magical. Whilst Baroque gardens are far from natural, the position if its natural elements in the border of these pictures next to the idea of the social implied in the validation of alcohol, alcohol served to the rich by the poor in this form of endless trays of drinks, as at the centre of human sociality made the whole a picture of the drunk destruction of our not only the idea but the reality of nature in the outside world – the erosion (itself a natural process) made catastrophic by human selfishness. Of course my reading may be fanciful. You linger a fair time to see this wonderful piece.

Returning by following an unauthorised path to the lakeside one that is authorised, we take another look at the St Gallen piece before confronting Runner [2015] (8). Looking at the catalogue now I wish I had taken more photographs around the piece but those blow give a taste. A multiform structure, made up in some aspects in geological layers as it seems, it looks at first like just two structures entwined that in their play create space between their attached closeness’s. The leaflet says that, though not figurative, the piece is ‘like athletes jostling for position in a race’, creating as they do asymmetries of captured shape in a process that is dynamic and ever-changing in feel, if not reality. You need to circle it to get more of the feel of motion, but this is genuinely a piece where I do not find figurative interpretation helpful. Cragg says of it that it manifests his interest in ‘the emotional life of form and its geometric and rational structure’. [11] This is good as long as we see how the geometric or other measured rational abstractions are reformed by emotion continually – how inner and subjective forces relate to what we like to think of as objective measures of the world. That is an idea not far from those of the playful and theatrical forms of the disturbed Baroque.

After glancing at the Atlas Fountain (see the image at the end of the blog) – as disturbing an image of a preformed world of the fluid playing over human shapes, even of the globe itself re-conceived in human thought – we ended our outdoor trip with a shape similarly, disturbing, Industrial Nature (2024) [9]. Daisy gets into the middle picture.

Cragg says that he conceived this form as a tension between an internal one that looks like ‘a structural geometric form’ but built extensions around it that ‘develop out into space’. I love that modified verb phrase ‘develop out into’, containing the issues of what is internal and external, present and emergent, and the projection of the introjected.

The issue of contain insides outside probably stopped us seeing the last ‘external’ form by Cragg, for we never found it – housed as it is in an inner courtyard in an outbuilding, Points of View is a triform maquette in wood, painted matt blue of other works with that name. the catalogue pictures are exquisite. I failed to see it, blame it on the weather. We decamped to the café at the house taking a seat outside on the lawn. After coffee I did the first inside tour, Geoff waited and followed after.

Given the circumstances, I felt I must work fast and though I looked carefully at each Cragg work, my summary here is deliberately selective. Starting in the Great Hall I saw McCormack (2007), Outspan (2008) – my favourite – and Red Square. Like Baroque art these pieces examine works caught up in folds, grooved valleys and seams, playing between the biomorphic and geometric, depending on angle of vision. McCormack is gorgeous.

Outspan is transformative however, like a huge almost mythological shell out of which a goddess might emerge, it can also look like a conception and the material reality of industrial process. From a certain angle (see the left detail in the collage below) it looks like the access to a huge ear, . No wonder Cragg says, (of the later smaller Red Square, which has no square in it – that ‘we only see the tip of reality. What’s under the surface of things?’ [12] In my photographs Red Square is seen only over the shoulder of the other pieces in The Great Hall.

Beyond the Great Hall is the newly restored Garden Room in which the psychological and profile form of personalities interact, in works like Bent of Mind (2002), Hollow Head (2013) and Level Head (2005). There is great play in the cusp of the most terrible of human binaries – the normal and abnormal – here.

I favoured the beautiful Woman’s Head (2015) in bronze but with an external appearance of stone. The Baroque fold – in sculpture and painting – is rarely as rich as this, where fold and layer meet as concepts of joining and continuity. The Head is one form but also many – purely beautiful but ever so unsettling, like the contradictions involved in a grieving mother being seen and performing self-management.

The next room, though the catalogue deals with them last, is modern works in glass. This whole room is enchanting for the beginning and the end of each sculpture is compromised by their dependence on light and the interaction between outer and inner forms, beautiful in each form – sometimes moulded from semi-melted existent forms (drinking glasses) ar merely suggestive of them, all radically destabilised in appearance and apparent structure. They stand tall only to the sound in one’s head of glass falling and smashing, fragmenting almost into tiny mirrors.

Nowhere is the internal and external form, changed anyway by how light falls onto and into the object as in Bodies (2021), I cannot get the effect out of my mind.

Sometimes the relation of internal and external is more legible conceptually, as in the following work, whose name I failed to record. It has the boldness of a growing fungus.

But how beautifully does light and shadow create complexity in this piece, called gnomically Visible Man (2016), in which a troubled portrait bust might be present. It is for me – more troubling than Caligula.

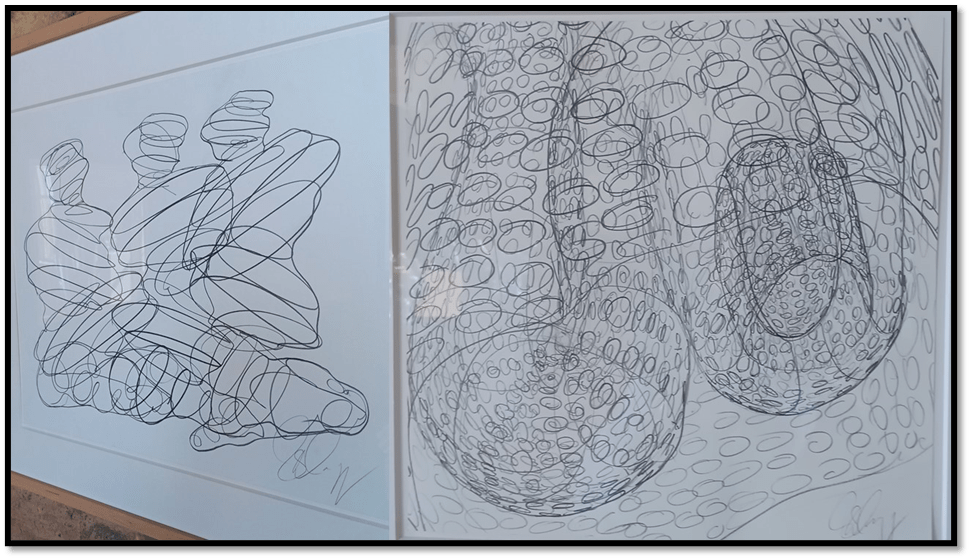

In the same room are the most beautiful works on paper. These can be treated as preliminary studies for glass for they have the same interest in transparency in overlaid forms, as the geometric becomes organic – as human figure in the example on the left below, but of marine animal in the second, where folds and grooves that mediate between inside and outside are compared. The catalogue chooses other examples to illustrate but of those I choose they are both called Untitled, (from 2005 and 2015 respectively).

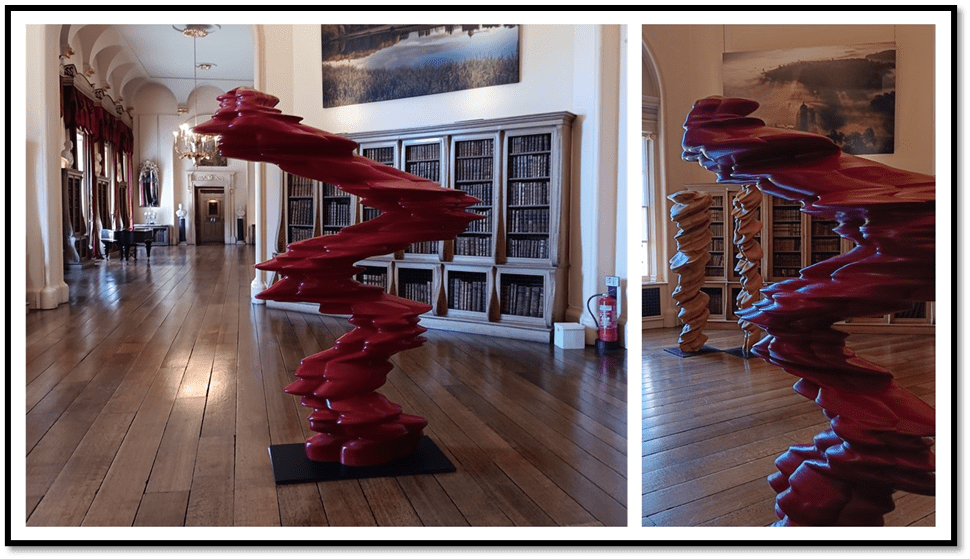

In the final room (a long book-lined gallery called the Octagon for its central feature (seeable better from the outside) are toe works of strange beauty. Pair (2015) an unpainted wood sculpture formed I think from plywood pressed together but so polished the layers look like wood grain are described as dancing forms, but like the Runner the concepts may be more abstract than figurative. Yes, I see ‘rhythms and movements’ but also a study of the interplay of proximity and distance in all relationships as we look around them – wholeness and fracture.

The one I leave till last called simply Red Figure (2023), feels to me highly disturbing, perhaps because of its blood-red figure, but more because of its recall of a posture of felt pain and agony – physical and / or psychological so the join between those modes of lived pain can’t be seen It is intense but it is also defensive, crouching for an attack in reaction to fear. I didn’t like it but I also loved it.

And yes, in that geometrically conceived room (the only holding most of the capricci), it seemed incongruous – or did it, for, even in that interior the settled id disturbed by external light, causing those aristocratic rooms to echo with their historical fragility. And go back to the window and look out at the Atlas Fountain. Isn’t it rather clear that the world Atlas holds on his shoulders, as well as his inner world, spouting fluid all over his apparently solid body, and fired at from cornucopia from the fringes of his world is not as stable as he’d like to think he is.

History of Castle Howard webpage picture: https://www.castlehoward.co.uk/visit-us/the-house/history-of-castle-howard

The Tony Cragg exhibition closes on the 22nd September. You will need to be quick in planning to see it. But see it, you ought. Castle Howard is a joy after all.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Tony Cragg cited in Jon Wood (Ed.) [2024:27] Tony Cragg at Castle Howard Castle Howard Estate Ltd.

[2] Jon Wood (2024:8f.) ‘Tony Cragg at Castle Howard‘ in Jon Wood (ed.) op.cit., 6 – 11.

[3] Ibid: 8

[4] Tony Cragg cited in Jon Wood (Ed.) [2024:27] Tony Cragg at Castle Howard Castle Howard Estate Ltd.

[5] Jon Wood (2024:8f.) ‘Tony Cragg at Castle Howard‘ in Jon Wood (ed.) op.cit., 6 – 11.

[6] https://www.castlehoward.co.uk/visit-us/the-house/history-of-castle-howard

[7] Christopher Ridgway (2024:83) ‘Sculpture at Castle Howard’ in ibid: 83 – 86.

[8] Ibid: 84

[9] Jon Wood (ed) op.cit: 16

[10] Ibid: 28

[11] Ibid: 39

[12] Ibid: 56