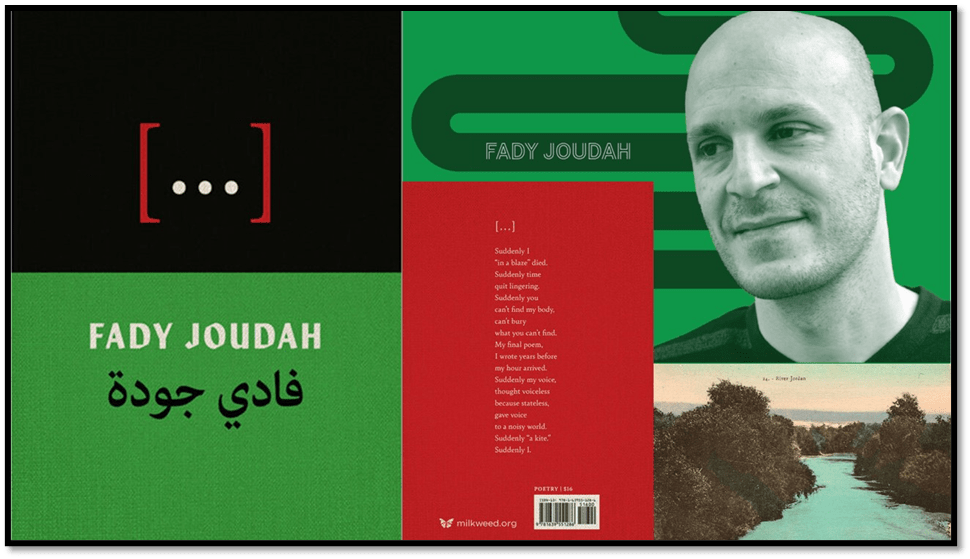

Fady Joudah was asked in an interview by Aria Aber In The Yale Review in February 2024 that was deliberately focused from the start on how the current war in Gaza might have changed his work, ‘What do you think the responsibility of the poet is?’ He replied: ‘The poet does not have a single kind of responsibility, nor is the responsibility defined by the magnitude of an event, private or public. … The responsibility of the poet? … We keep talking about it because it is relentlessly mutable, pluripotent. … I often think that the responsibility of the poet is to strive to become the memory that people may possess in the future about what it means to be human: an ever-changing constant. … A language of life’. This is a blog on Fady Joudah’s volume named […] Poems, London, Out-Spoken Press.

Aria Aber In The Yale Review in February 2024 in her interview with Fady Joudah, a great American-Palestinian poet and translator deliberately focused from the start on how the current and vilest yet phase of war in Gaza prosecuted by the might of a globally padded state might have changed Joudah’s work, Fady Joudah was asked also in that interview: ‘What do you think the responsibility of the poet is?’ He replied:

The poet does not have a single kind of responsibility, nor is the responsibility defined by the magnitude of an event, private or public. … The responsibility of the poet? … We keep talking about it because it is relentlessly mutable, pluripotent. … I often think that the responsibility of the poet is to strive to become the memory that people may possess in the future about what it means to be human: an ever-changing constant. … A language of life.[1]

Ask a poet a straight question and by necessity you get a far from straightforward answer. Joudah speaks in the same interview of varying his writing over ‘multiple registers’ and being ‘obsessed with the dance between clarity and idiosyncrasy’. We set the register of our writing – the formality of the words chosen, and syntax deployed -usually by knowledge of the function this particular piece of writing has in the external world and knowledge of the tolerances of our audience, should we have one in mind. In poetry like Joudah’s, so the poet claims himself, the function is often idiosyncratic, turning on himself and his own formulations of thought and language struggle to make sense to others. It is as if, at certain times, the primary reader, being himself, knows the direction in which his writing heading, and thus allows itself momentarily a merely private function, which he allows other readers to overhear: it is a refined means of talking to oneself, whatever that means. On the other hand Foudah sometimes and mainly chooses an appropriate register that aims to clarify his subject in an appropriate language and to the level of the audience’s presumed capacity to understand what is said, although even here he makes no commitment to keep to a single subject or audience and hence will allow his linguistic register to vary.

This in itself is a common manner of preceding in poetry. John Stuart Mill expressed it thus:

Joudah in the Aber interview cites J.M. Coetzee as a model for his practice, citing this:

The masters of information have forgotten about poetry, where words may have a meaning quite different from what the lexicon says, where the metaphoric spark is always one jump ahead of the decoding function, where another, unforeseen reading is always possible’.[2]

This is different from private meaning of course. It is about alternative meaning. Nevertheless, at this point people who dislike poetry get up and say that is just WHY they dislike poetry, sensing that its foothold in subjective sensitivity to the full range of the emergent meanings of words in concert makes it merely a way of mystifying the world, and allowing any reader to claim that their idiosyncratic reading is worth as much as anyone else’s, if no more. But that isn’t what Coetzee is saying. He is making room for alternative meanings of a word based on shifts of register that can be evidenced, as a way of seeing a thing from many perspectives, even experimental and forbidden or censored ones. And this is the beauty of these poems’ title, […]. However that title is not always well read, its formal uses forgotten. The symbol … indicates an ellipsis, elements (usually words) omitted from a passage of writing. However used bare like this they can indicate an ellipsis that is created in discourse itself, wherein a speaker has their word cut into and quashed by another, or by their own desire to revise what they say or because, for some reason they have lost the thread of their thought or narration process. When surrounded by brackets, they indicate elements omitted not by person who would have been the author of the words had they been said but by another person (or the same person enacting a different role) acting as an editor -or censor – of those words. Joudah discusses this in another interview with Boris Drayluk, who calls this bracketed ellipsis a ‘double erasure’, in The New Inquiry. Drayluk starts by focusing on the title of the volume and many of its lyrics in the contents of the volume:

It is impossible to ignore the double erasure figured by the title of the book and of many of its individual poems: an ellipsis, bracketed. I can fill in the blank with any number of words, but the blankness appears to be the point. “Daily you wake up to the killing of my people,” you write, and then ask, “Do you?” Could you speak about the silence, or the silencing, the title indicates?

Once I begin to speak about the silence that remains, it is no longer a silence. My translation work on Ghassan Zaqtan’s selected poems, The Silence that Remains, honors this. “I am not your translator” is another line in […]. It is an echo of Baldwin’s “I am not your Negro.” As a Palestinian in English, I am not a cultural bridge between the vanquisher and the vanquished. Perhaps […], too, is an exercise in listening. Listening to the Palestinian in English does not mean that the Palestinian is always talking. We also need to learn how to listen in silence to the Palestinian in their silence. So far, when a Palestinian goes silent, it means they are dead or violable, digestible, liable for further erasure or dispossession. English has not begun imagining the Palestinian speaking, let alone understanding Palestinian silence.[3]

Silence is in Joudah’s formulation here is not a richness of possible substitutive meanings underlying language but merely an absence, even perhaps a ‘death’ of what can or should be spoken. To compare his purpose with Baldwin’s I Am Not Your Negro is to launch a challenge to anyone wishing to appropriate Palestine discourse for their own purpose, even those (as we shall see) supposedly in empathy with Palestine, perhaps even Joudah himself, who is not now simply a Palestinian, however much his family has suffered (and some of them died) but an American citizen speaking in a foreign language, ‘in English’ and therefore let empathisers or attackers digesting Palestine, making it ‘liable for further erasure or dispossession’.

At some level all these poems can do is indicate they will not speak, at least not speak FOR PALESTINE. In a rather difficult (to read clearly at least) review in Words Without Borders, Joyelle McSweeney adds that ellipses may not only be censored material but that which is literally ‘unspeakable’ because we do not yet posses the words in which to speak the truth. The ellipsis indicates then a duration of time in which we all wait for that which we mean to say. In her words:

The title is, to use Joudah’s word, unspeakable. It indicates, as Joudah and as several readers have suggested, a “Palestinian silence,” but also, to me, a silence that implies an interval of waiting, specifically that glyph you see on your iPhone when a message is being typed but has not yet arrived. The iPhone, that deliverer of the worst and best news, the videos of destruction, denial, grief, and glee, has a role to play in Joudah’s poems: “The truth rides photons, always arriving / beautiful, like God, periodically dead or terminated.” Importantly, these photons are not just beautiful, but periodic, as if termination is not final but something that must be borne, again and again. We are nowhere near the end of the end of the world.[4]

If the ellipsis is a duration of, it speaks silently McSweeney goes on to say to the ‘terrible interval’ at the beginning of the genocide in Gaza, where personal loss may be overwhelming but not as much as the sense that the only ending of this ‘conflict’ (so inaccurately thus named) is the extermination of Palestine as if it were the symbol of a species undergoing ecological extinction (a theme the poems rehearse often). I get what McSweeney says here but I feel it, like most formulations that translate Joudah into one’s own critical terms, it forgets that it is not just a period in which we passively await the arrival of words that will be said, but one in which we actually do have suitable words (genocide being one) but that they get externally censored either by enemies who want these truths repressed or by liberal America’s self-belief in its fairness to both sides in any conflict and its distaste for words that denote ‘extreme’ realities. In another interview with The Boston Review (name of interviewer not given) Joudah describes the ‘terrible interval’ denominated by McSweeney as a period in which he couldn’t help but write the unspeakable into a book as ‘unspeakable’, as […]: ‘I needed to survive the hours of experiencing my annihilation livestreamed’. But make no doubt about it, this is not just because he is waiting for or does NOT KNOW the words to say, but because he knows that that part of him that speaks as a Palestinian in Arabic that is untranslated has words liberal America hates – that for genocide included.

The merry-go-round of the Palestinian tragedy is, in part, a function of the denial it encounters in English. There is little meaningful believability applied to what Palestinians have been speaking for decades. From this, erasure and ghosting of Palestinians follow. In other words, I have been living, speaking, and writing these poems for years. But to say the poems needed a genocide to write them? The believability index for a Palestinian in English has risen a little over the last four months. It is disturbing to notice that some solidarity is not much more than guilt over complicity. It remains largely unimaginable in English that a Palestinian knows and has known what they are talking about. We are neither prophets nor mad. The simple truth is sometimes the hardest to see and accept.[5]

There is a sense that ‘English’ itself, the language, censors the statement of truth, and hence in part that part of Joudah that translates himself in English just as he translates Mahmoud Darwish’s Palestinian words. Palestinians are censored not just because they can speak Arabic but because stating a ‘simple truth’, that the aim of Israel in the Middle East is the genocide of people and the appropriation of land for settlement by itself is though ‘unspeakable’, and accused of Antisemitism or worse. English discussion, after all, of Palestine lies entirely under a self-chosen censorship because we want to believe a harsh truth to be more nuanced.

The truth of censorship is felt by Joudah in rather direct ways in the United States he tells us as early as 2021, where in The Los Angeles Times he wrote about his failure to get one of the poems in his volume published in The New Yorker, and of similar experience with other literary organs in the States. The poem is one that directly blames English speaking, especially that committed to complex abstract words of Classical origin (‘dilatory, attritional’) , of refusing to speak truthfully of Palestine, as here in lines, beautiful but painful, in their truth-telling in the pe volume published in 2024:

You who remove me from my house are blind to your past which never leaves you, blind to what’s being done to me, now by you. Now, dilatory, attritional so that the crime is climate change and not a massacre, so that the present ever ends .[6]

When the poem was being refused, it was slightly different, perhaps more conciliatory for in the earlier version the metaphor of the mole further blames human consciousness for its tendency to choose to allow real massacres to occur rather than talk about them. A mole is blind for a reason wherein biology adapts to environmental necessity, whereas humans choose blindness to its own past complicity with extinctions human and animal, finding euphemisms for those destruction that remove awareness of human agency in causing the thing euphemised.

You who remove me from my house

are blind to your past

which never leaves you,

yet you’re no mole

to smell and sense what’s being done

to me now by you.

Now, dilatory, attritional so that the past

is climate change and not a massacre,

so that the present never ends.[7]

The 2021 article that accompanied that version of the poem which then had the title Remove goes on to point out that English-speaking cultures sanitize oppression, unlike Arabic, ‘exterior to English yet born internationalist and shall remain so neither thinking it is the center of the world nor surrendering to the imperial center as the primary source of its future liberation’. The article makes it clear that both internationally operative Western capitalist hegemony actually shuts gates to the truth told in Arabic about Palestine that exist even in the language. Every aspect of Palestinian silence is an imprisoned one, navigating gatekeeping controlled in English. As a result Palestine is ‘ghosted’. And ‘if anyone wants to come out in the light a little. They must comply with normalized stipulations that placate hierarchical structures, editorial controls, and fact-checking rigour, which may or may not apply equally to all writers on Palestine. No wonder Bartleby killed himself’.[8]

The reference here to Bartleby the Scrivener, the short story by Herman Melville is a fine example of the fact that America has some awareness in it of the oppressiveness into which it also allows Joudah to fit as an American writer, provided he does not express truths simply, as in the case of genocide they must be expressed, understood and believed to stop the processes of settler colonialism in ways that could not have happened in America and Australia, for there genocide was seen as an acceptable alternative to the refusal of native populations to conform with their oppression. He has a name for this process, from Herbert Marcuse, ‘surplus oppression’ or ‘repressive tolerance’. In the interview with the Boston Review Joudah expresses the point thus: ‘English writes the Palestinian presence through censorship and surveillance’.[9]

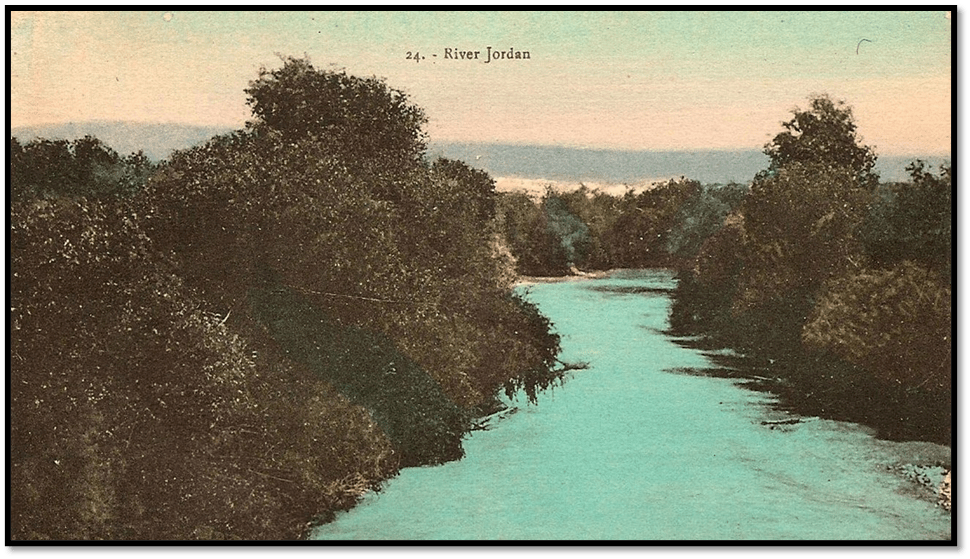

Among the most censored of phrases in the discussion of the Palestinian world is mentioned by Aber in her interview with Joudah. Ashe says: ‘We are in a moment of severe censorship; language feels charged and flammable. In Germany, for instance, for example, protesters are forbidden to shout the slogan “From the river to the sea”’. She says this before in her own way going on to ask why the volume of Joudah’s title is […], which she describes as a thing that ‘ruptures and silences’ discourse. Joudah’s answers to Aber seem sometimes to strive to undermine the surety of the discourse between them, so that when she changes tack in her questions to ask about hope’ in the poems, he gives an answer so gnomic that returns us merely to the issue of what is meant by being able to use the phrase ‘from the river to the sea’: ‘The role hope plays in […] is from the river to the sea’. I cannot be sure that this exchange ever reaches a resolution. What I think he means by the description of hope thus, and in the context of their talk about censorship, is that the phrase ‘from the river to the sea’ is unlike the naming of nations and empires in the past civilisations of the globe. The Jewish reading of the phrase, accepted by Western governments, is that it calls for the genocide of Jews in Israel to establish an entirely Arab and Muslim state. Joudah is I think insisting that the phrases refuses such a hopeless scenario for something where boundaries are fluid – literally so – the river Jordan and the Mediterranean sea. This is surely what he means by:

Civilizations come and go. Hope has no ethnicity, no nationalism, no identitarian limitations, no monopoly on time. We can make that choice about hope.[10]

Contemplate the River Jordan, as it looks below and we do not see a human boundary, with all the false geometry of colonial and settler nation-making with their dream of separated populations in identity categories governed by human constructs like nation, identity, and ethnicity, but a natural phenomenon, like the sea the river sends us from its banks on a journey too across the historical Palestine without the Apartheid-like laws of Israel as it currently is, intended to favour one group over another.

From the river …..

And this is where the ‘language of life’ that poetry might be meets the language where borders become porous between nations, identities, ethnicities, even genders and the species of living biological forms. To the Boston Review, he stated it well. It is a moment when even language (often seen as the repository of symbolic humanly constructed identity diversities but for no good reason is no longer certain of its own boundaries. For, he says in that last named interview:

Language dies when it is too certain of itself. …. As for my relationship to Arabic and English, I live in both. They inform each other. It is a great feeling to exist in the domain where languages no longer discern or insist on where one begins and the other ends. This is how language lives.[11]

This is clearly not the aspiration of a practical or even pragmatic politics in our present world and hence Joudah remains in the realm of the double ellipsis – both choosing to be and made silent, both aiming for a Palestine that does not recognize only human identity constructs but the hope of developing communities across and between different kinds of boundaries and fluid in their meeting points of sameness and difference. So how does this relate to reading […], which names itself by a flow of dots between two banks like the River Jordan. This is then a poetry that must in a sense go beyond rational boundaries Its aim is to SURVIVE the present rush to catastrophe, not only in Middle East politics but in the politics of the ecology of living and non-living systems. Again the Boston Review interview is clearest on this:

Through art, in a time of genocide on livestream, I am leaving a record of a Palestinian’s words beyond the documentary and outside the audition for my humanity in English, which in any case is more easily received when I am a spectral existence. I found it easy to juxtapose poems of desire, eros, and ecology with those of disaster. I wanted to write a book of survivance.[12]

Let’s take the opening poem […], which sets up the lyric voice naming itself ‘I’ as incomplete – spectral if you like. The whole plays upon the notion of being ‘unfinished, which even from the get-go hovers between life and death. The ’business’ that ‘did not finish me or my parents’ is a matter that leaves me still alive for a business that finishes you, kills you potentially. But that business bothers and unsettles all the named family members her – the enjambment between lines through the whole of the opening refusing to rule out ambiguities where my parents bother my children, just as in another reading the ‘business’ does, presumably in part the business of war in Palestine. But maybe ‘I’ is the voice of the lyric itself, momentarily claiming incarnation and writing itself, perhaps with a ‘feather’ to use as a quill pen. But in the poem ‘quill’ is a verb, which in one of its meanings refers to the business of folding paper to make original art or design works or embellishments thereof, rather than writing on it.

Does the lyricist, or the poem ‘forget Palestine’ as it labours to make itself whole, finished, but perhaps too finished in the sense of ended, dead and now inert, no longer in living process. The enjambment in the lines forces us to realise that what we forget is not Palestine as a whole but its own method of ‘remembering’ (or putting things or ‘members’ together). The poem and quilling is a kind of art that involves marks being made on paper or other resource, but ‘marks can also be bruises’, the remnants of violence.

The poem inevitably becomes to be about time – the time it takes to read it (for the reader will’ finish the business’ of reading the poem too in a sense. But the history of Palestine in real time is a history of dismembering (of land, communities and people, and the hope of re-membering what is dismembered (from the river to the sea). The marks of violence don’t even start in the 1948 Nakba ( النَّكْبَة), but the present onslaught through Gaza and its peoples is to many Palestinians a continuation of violence and displacement from then. Hence ‘I’, the spectral voice o poem, poet and the domain of Palestine, seeing its ‘marks’ for life’ registered on it must embrace being ‘unfinished; so that these things can say of their becoming:

I write for the future because my present is demolished. I fly to the future to retrieve my demolished present as a legible past. To see what isn’t hard to see In a world that doesn’t.[13]

The themes I have spoken about above are current here. The denial of genocide is a denial, like that in North America, that will continue to be denied by perpetrators of it until it is ‘finished’, and hence no-one can either know or even ‘see’ the present for what it is,f or the world is entrained currently not to see what ‘isn’t hard to see’. What is denied not that the cityscapes of Gaza are demolished but that they are actively being dismembered, as the claw of the JCB in the collage below reminds us.

And only this way of ghosting through time will I think allow us to find the reason that there is little to say but to remark one’s ‘terminal velocity’, the speed with which the process is being pushed to an end we do not and cannot want, if we are Palestinian … but, no!, If we are human! This is why, as Joudah tells Boris Dralyuck, and which McSweeney quotes in her review: “I am far more concerned about the day after the livestreamed genocide of Palestinians stops. The day after is the longest day. And it is just as unspeakable.”[14] For if the business has finished the aggressor has won.

In the situation of Palestine when no-one really can ‘wake up’ (the word has resonance with awareness not just of rising in the morning) then what people see is never ‘killing’ for the word is ‘Censored, the news. Shadow banned. McCartheyed’ but look instead for ‘Daily, your nuance’. Its nuance treated as a sedative to keep us asleep.[15] There is little hope of clear sight of the kind when at last:

… old tricks find themselves out and genocide is seen through, this year or the next decade, and scholars sign off on it.[16]

Because of this even the word ‘cease’ in ‘Ceasefire’ loses its clear meaning, because we without ‘wisdom’ except as a word we like to use, prefer its repetition without consequence to implementation: Repetition won’t guarantee wisdom, / but cease now / before your wisdom is an echo’. The beauty in these lines are that that they echo the word ‘cease’ as if it were a quotation from the end of King Lear, : ‘Fall and cease! indeed I think it is a near quotation, for in that play too and at that point we are urged to ‘differentiate / between the dead and the not-here’ by Lear himself bearing the body of his daughter, Cordelia.

LEAR; …. That heaven’s vault should crack. She’s gone forever. I know when one is dead and when one lives. She’s dead as earth.—Lend me a looking glass. If that her breath will mist or stain the stone, Why, then she lives. KENT Is this the promised end? EDGAR Or image of that horror? ALBANY Fall and cease![17]

In Lear what Albany wants to cease is the motion of the Wheel of Fortune, but what Joudah exposes is that our wish for peace is as thin of our true memory of the meaning of Martin Luther King’s mission on MLK day.. Instead we hope repetition is all we need for wisdom.

Desire (and even sex) enter into the double ellipsis as well as the subject of Palestine because real consideration within them of the parties involved too is too often substituted for by one asserting power, and sometimes violence, over the other or others. Rape is the equivalent of colonising the colonised – the same binary. The best poem exploring this is poem […], before the Dedication.[18] It is a poem about how in language we differentiate or even conflate one person from, or with respectively from another. Language uses relationships – very fluid ones between words like ‘you’, ‘we’, and occasionally ‘I’. As McSweeney perceptively notices:

It seems wrong but also right that “you,” deployed in English, implies a target, which we call by the euphemism “addressee,” and if no target is available, the reader or poet may insert themselves. Lyric’s intimacy as an instrument of war.

Though not speaking of the poem I talk about here, the same applies. The poem I refer to ‘you’ in the opening can be the other he addresses, perhaps a lover to whom he is conjoining, or an aggressor, perhaps Israel, but it could also be the reader, or even himself thinking himself as usual as ‘unfinished business’’: ‘You will be when we be’. Will our separate identities depend on our conjoint identities, fluid internally? There is a love match here but also a threat of unwanted intrusive penetration:

We absolve you of reparation, promise you forgiveness. How long before you enter us to leave yourself?

Sexual penetration leaves a trace of the rapist in the raped, but there are various ways in which you van leave yourself’, including just abandoning me by retreating. A coloniser enters a colonised land to leave settlers, this was the process prior to and in the Nakba. The lyricist does not know if ‘we’ are separate or different or somehow dual: ‘we a camel / that went through. One lump or two, what’s the difference’. The reference to the parable of the entry to Heaven, in that it can be easier for ‘a camel to enter the eye of a needle’ is also richly there, perhaps varied by any presence of the parable in the Quran. The reference to political ‘vanishing’, well established in Israeli Defence Force practice is cruelly there in: ‘You will miss what you vanish. ? You will be when we be’. Is it not that the poem proposes that no forced entry can ever be a victory for no-one gets the chance to be ‘we’ in a significant and shared way.

I will leave my reading of that poem, although it casts light on the discussion of the relationship of oppressor and oppressed in […] on pages 26 -7, which even gets trembling near the negotiations in the Palestinian situation now, though terms like ‘hostage’ are clearly metaphors with potential wide-ranging reference. What is clear it is about whether the oppressor who claims to be one with us, ever can be, whilst our past history remains hostage to the fortune of bloody war. If Israel’s claim to ‘host’ Arabs, or America’s in hosting a Palestinian like Joudah, safely in each case means anything, it becomes part of this mix in the distinction of who is intended by pronouns like ‘they’, ‘you’, ‘I’ and the ‘we’ who never emerges in this poem:

“You’re among the lucky ones,” they said. “Your oppressor’s heart is your host. And it recruits.” “But I’ll have to wait my turn,” you said, “before my story, held hostage, is released.”

And as we know many US publishers refused to ‘release’ Joudah’s story in his poems, and they refuse to ‘release’ control of the story of Palestine to those who experience it first-hand. The you last used in the last quotation is so fluid it could be anyone speaking, even Israel awaiting the hostages it creates no chance for the release thereof.

There is too much richness in these poems for me to pretend I cover their themes and their devices for engaging us in what I have said. What is clear is that this is poetry of a high order that cannot easily be ‘finished’ off with a meaning that will satisfy everybody. The point is in the reading engagement with the poems – only that releases meanings held hostage with them. These poems are about how we read each other, even accept the statement that the poet will not appease you or make you feel you are in the best of all possible words.

One poem insists:

Top conscience, I’m not okay. We’re not okay With your genocide bouquet.[19]

The conceit in this poem (I mean the literary critical notion of the conceit here as explained in the link) is that invasion and genocide is like conducting an unequal relationship and insisting to another that neither ‘I’, nor ‘we’ are okay, unless each person says so and genuinely feels so. A bouquet bought from the garage on the way home will not do the trick of making everything okay at home, but when the bouquet masks an invasion of mass arms this is no loner a literary conceit but a real invasion of claims of ethnic or national superiority.

In my view a great poetry will never be a ‘finished’ business but one that continues into repetition of our reading through the repetition of the themes and their dispersal into different contexts of meaning-making. If there can be winners in poetry, this volume must be a winner! The meaning of these poems I do not want to further discuss but its secret lies in the prose-poem ‘Dedication’. Meet me there and discuss it,, or better still, let us feel it reverberate in our conjoint silence, interrupted only by the music of our own bodies feeling each other ‘s commonality and difference. My feeling is that one of the most important process in the metaphors in the poems is the comparison of ‘scale’, the difficulty of discerning what is small and what is large when the subject is belonging or not, pain and suffering which indicates a means of comparative measurement, a musical continuum of sound and something about the inability to understand magnitude’s overwhelming effect on one (the phrase ‘orchestra of thirst’ stays with me. Compare this moments in Dedication, where a disease helps descale suffering, but not in a way that comforts with a poem about whether killing children is a little or a large event in life:

‘To those with dementia: may it save you from the full scale of terror. To forgetfulness when a mercy.[20]

They did not mean to kill the children They meant to. Too many kids got in the way Of precisely imprecise One-ton bombs Dropped a thousand and one times Over the children’s nights.

Of course this works by enacting contradictions that play over the meaning of a phrase like ‘mean to’. But it lives too in the quality of the rhythmic measure of the line set against the quantifications over which it obsesses: weights and measures, and concepts of the reliability of our measurements (‘precisely imprecise’).The conceit of this poem is the language of scientific research studies that set quality and quantity against each other.

This is what the bomb-droppers did not know they wanted: to see if others will be like them after unquantifiable suffering. They wanted to lead their own study, but forgot that not all suffering worships power after survival. [21]

To whom does the bomb-dropper want these children’s following survivors to be like? Themselves, or still like the children who had learned to hate the oppressor. The point is that questions of survival will not be meaningful in contexts where to know others (animal or human, men knowing women and vice-versa) is seen as a matter of’ leading’ a ‘study, and the operationalisation of success through the quantification of power after a suffering that is unquantifiable. This is the greatest of poems but the most awful of experiences.

I give up. I am in awe of Fady Joudah as a poet who makes me think if poetry matters and how.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Aria Aber (2024) ‘Interviews: Fady Joudah : The poet on how the war in Gaza changed his work’ in The Yale Review (Feb. 28, 2024 ) Available at: https://yalereview.org/article/fady-joudah-interview#:~:text=One%20of%20these%20is%20the%20Palestinian-American%20poet%20and

[2] Cited ibid.

[3] Boris Dralyuk (2024) ‘When It Takes Root in the Heart: A Conversation with Fady Joudah’ in The New Inquiry (online) [March 11, 2024] Available at: https://thenewinquiry.com/when-it-takes-root-in-the-heart-a-conversation-with-fady-joudah/

[4] Joyelle McSweeney (2024) ‘“Palestine in Arabic is Always Alive”: Fady Joudah’s [. . .]’ in Words Without Borders (March 27, 2024) available at: https://wordswithoutborders.org/book-reviews/palestine-in-arabic-is-always-alive-mcsweeney/#:~:text=Joyelle%20McSweeney%20reviews%20Palestinian%20American%20poet%20Fady%20Joudah’s

[5] Boston Review (2024) ‘“We Are Neither Prophets nor Mad”: An interview with poet Fady Joudah about writing his latest collection, […], amid war in Gaza’ in The Boston Review (February 29, 2024) available in: https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/we-are-neither-prophets-nor-mad/#:~:text=An%20interview%20with%20poet%20Fady%20Joudah%20about%20writing

[6] Fady Joudah (2024a: 71) […] lines 1 – 9 in Section IV, […] : Poems London, Out-Spoken Press.

[7] Cited Fady Joudah (2021) ‘My Palestinian Poem that “The New Yorker” Wouldn’t Publish’ in The Los Angeles Times ( June 7, 2021) Available at: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/my-palestinian-poem-that-the-new-yorker-wouldnt-publish/

[8] Ibid.

[9] Boston Review op.cit.

[10] Aria Aber, op.cit.

[11] Boston Review, op.cit.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Joudah 2024 op, cit: 3

[14] Dralyuck, op. cit. & McSweeney, op.cit.

[15] Ibid: 4

[16] Ibid: 7

[17] Shakespeare King Lear Act V, Scene 3, line 310ff. Available at: https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/king-lear/read/5/3/?q=cease#line-5.3.318

[18] Joudah 2024, op.cit: 76

[19] Ibid: 25

[20] Ibid: 79

[21] ibid: 12

2 thoughts on “‘A language of life’. This is a blog on Fady Joudah’s volume named ‘[…] Poems’, London, Out-Spoken Press.”