A great film worthy of the inimitable Lee Miller: Lee seen by Geoff, my husband and I at the Odeon De-Luxe Durham at 2.15 p.m. on Tuesday 17th September 2024..

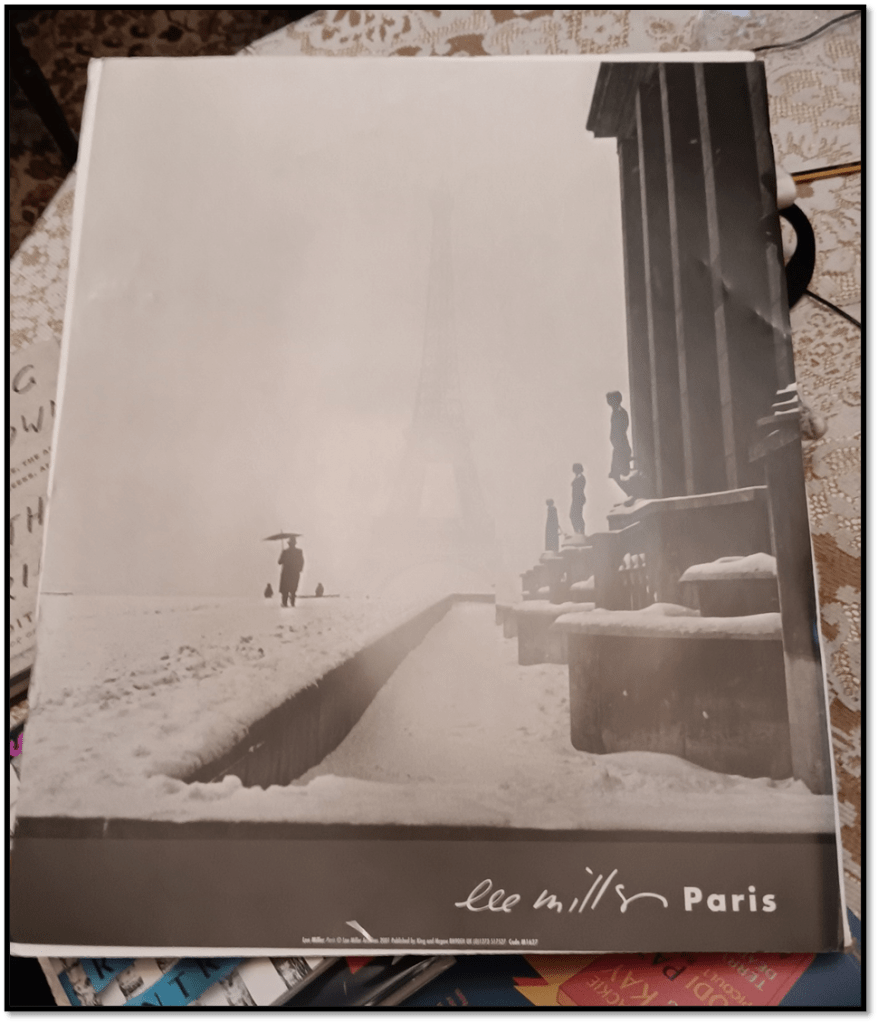

There are lots of reasons why I love Lee Miller. For many years she came up in biographies of artists I read: of Picasso, Man Ray, Roland Penrose. Each time you read her name, or even better saw a photograph of hers, you got the impression of much that lies behind the reference, of a person not really designed for a bit role in another life, but one who ought to be treading forth front stage, spotlighted rather than sidelined. I have a poster of a print of hers of the Eiffel Tower. We are finally getting round to framing it, showing the Eiffel Tower in Paris as a kind of ghostly icon across the snow in the mist and distance.

There is beauty here and understanding that cannot be explained merely by the fact that in Paris she was taught photography by Man Ray, who was also her lover, but of whom she bored, sexually at least.

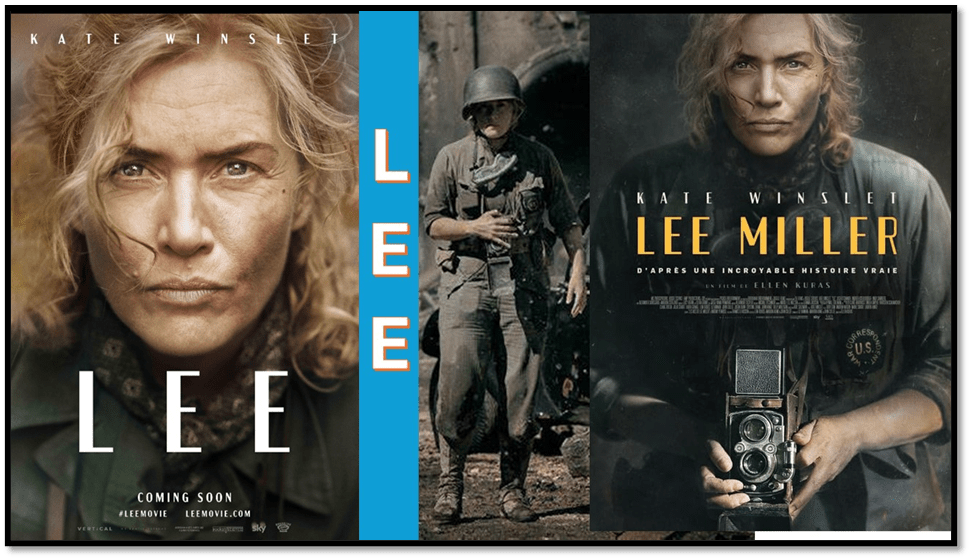

However, Lee Miller kept coming back into my life. In Alex Garland’s Civil War, she is an icon related to its hero female photographer, played by Kirsten Dunst, who is named ‘Lee’ after Lee Miller, as she tells her reluctantly-gained young female protegee in that film. Civil War was a film Mark Kermode disliked at the time of outing, but in praising Lee – quite fulsomely, whilst allowing for faults of over-compression, because ‘it tries to do so much’, by using a framing narrative – he too recalled Civil War as significant.

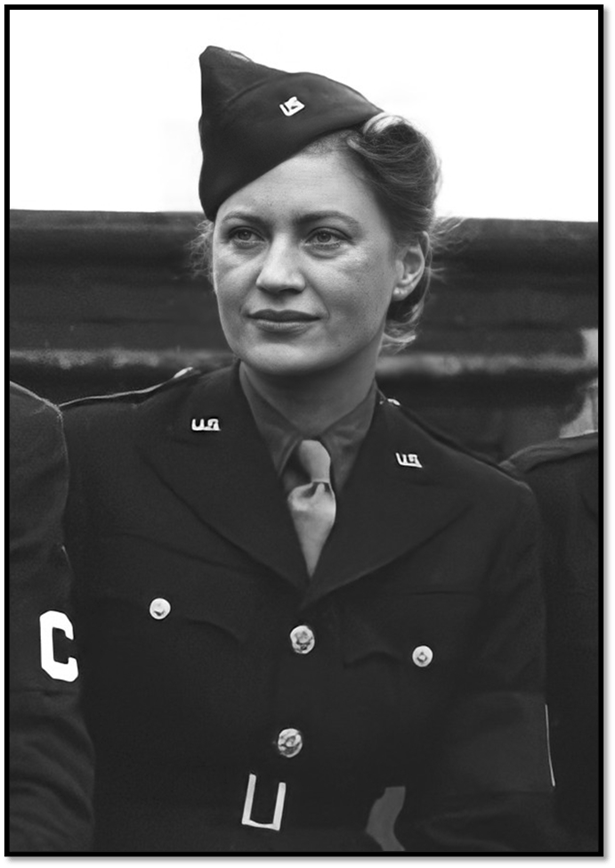

Female war correspondent Lee Miller who covered the U.S. Army in the European Theater during World War II (U.S. Army Center of Military History)

The reference to Miller In Civil War is no accident because Miller bound together in one artistic persona an interest in the use pf photography in art, fashion and art critique, was the associate and equal as an artist of not only Man Ray but also Alfred Beuys and Pablo Picasso who painted her portrait. In my blog on Civil War (see it at this link), I say of the reference to Miller: ‘The issues in framing a photograph are aesthetic and pragmatic … as well as representational’. On this I hang a reading of Alex Garland’s film. Hence, as soon as I discovered Lee’s release, I could not wait. There were downsides to the wait – in reading our copy of the i newspaper last Friday before a break in York, I encountered this rather strange review, in which Sarah Carson says that the film can be enjoyed only because Winslet ‘brings a gumption’ (whatever she means by that) ‘to the fashion model turned war photographer who was one of the first people to record the atrocities at the concentration camps, Dachau and Buchenwald’. Carson continues:

And thank goodness, because she is, sadly, the only dazzling thing in this disappointingly drab biopic about Miller, whose extraordinary life could have yielded a film exploring the professional oppression of women and the ethical responsibilities of pointing a lens at historical turmoil, but instead just feels like a Wikipedia page, a bullet points list of historical facts.

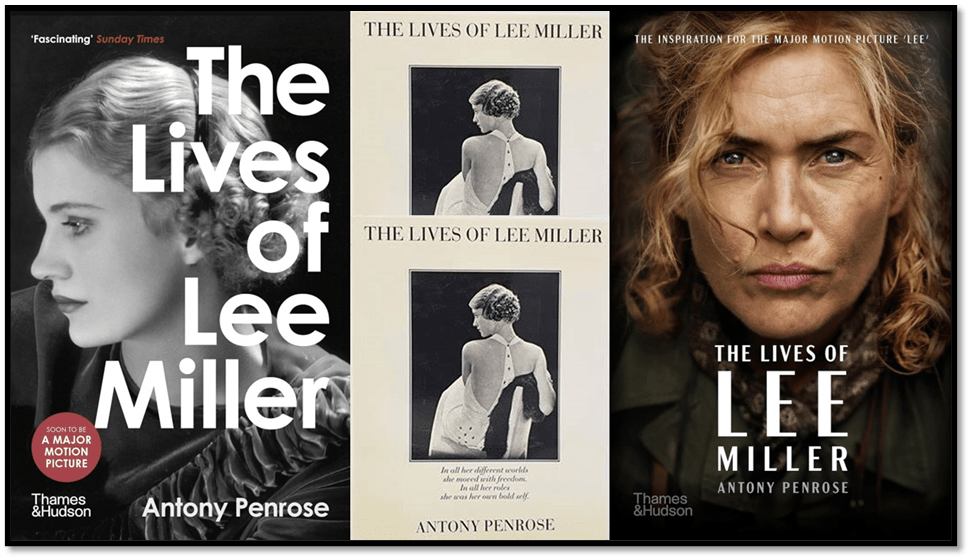

This film was nearly a decade in the making and made possible by the enthusiasm of Miller’s son Antony Penrose (who only discovered the extent of his mother’s extraordinary wartime efforts following her death) – but unfortunately it feels like a passion project gone wrong. “Look,” it seems to shriek, “I’m interesting!”, without any true effort on the part of the film-makers to make the narrative actually work on screen.[1]

Fortunately I saw Mark Kermode after reading this praising the film: no ‘drab biopic’ is mentioned at all and he sees lots of things in the film – great subtleties – missed by Carson. Hence, I kept up my enthusiasm, having booked to attend it on Tuesday 17th September after that, and made Lee Miller a feature of my weekend. For leisure reading I took the book by Miller’s son, Tony Penrose, on which the film is based. It grabbed me, as it must have grabbed Winslet with the stuff of a plenitude of lives rather than of one ‘life’, and out of which Winslet had to decide what to select in order to engage us. The book I read ON Kindle I wish I had bought in hard copy:

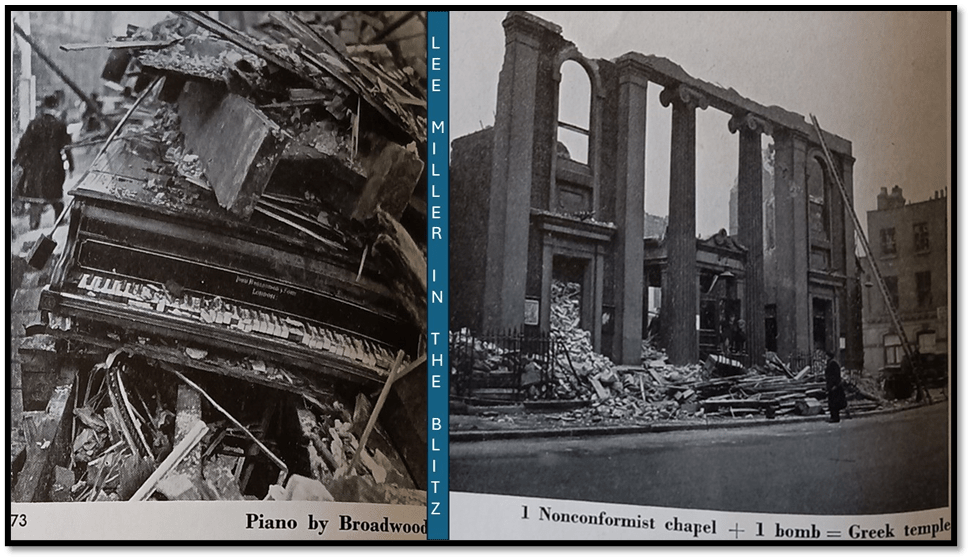

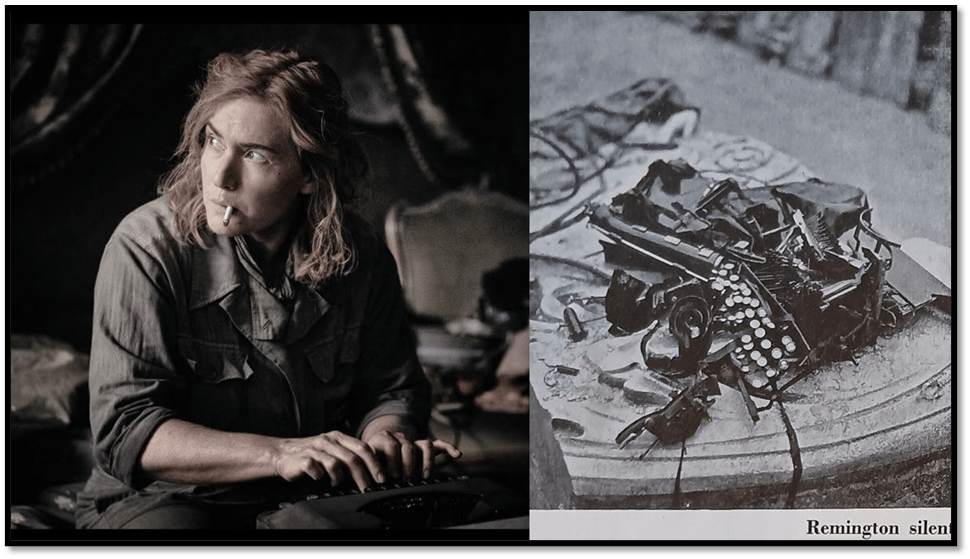

But at York I scanned the stalls at the Provincial Book Fair Association for her books. I found two. Her book on the Wrens, the only one in which she was sole author and photographer (which I could not afford at £150) and one she produced about the Blitz, Grim Glory which contained photographs from newspapers too and text that she found execrable, although her captions were good. At Waterstones on the next day I bought Tony Penrose’s 2023 selection of his mother’s photographs, with a gutsy Foreword by Kate Winslet. It was clear I intended to enjoy the film. The photographs, especially ones I had not seen, assured me I would, especially Silent Remington, which appears in one of the later collage graphics in this blog.

As for Lee’s wonderful captions – see the one on the right below from Grim Glory, expressed as an equation: ‘1 Nonconformist chapel + 1 bomb = Greek temple’. Miller constantly ties the tragedy of war not only to overwhelming response to mass death but also to the symbolic destruction of what she knew as culture. Hence the architectural joke but also hence the ‘Piano by Broadwood’: The smashed jaws of this grand piano will never sing again.

Sarah Carson might look at these photographs and say :Precisely! These are what the film misses!’ But that would not be true. If you know the photographs you will see the film mimics their making, overtly as when she arranges models for the photograph known as Fire Models of 1941, or of the soldiers wrapped in facial and hand bandages with the ‘lovely eyes’. Moreover, there are London street scenes in the film where, unless you know that the photographs are recreated as if the fact of Lee’s present in the film not the subject of art, except in the film’s own terms.[2]

I loved the Penrose biography and learned from this what a wonderful writer Lee Miller was, something I did not know. She used her skills to undermine in rhythmic prose the jingoism of many readers of Vogue with their easy and entirely fictitious English nationalism. Speaking of her work in the War Hospital she says:

The wounded were not ‘knights in shining armour’ but dirty, disheveled stricken figures – uncomprehending. They arrived from the frontline Battalion Aid station in lightly aid-on field dressings, tourniquets, blood-soaked slings – some exhausted and lifeless.

The doctor with the Raphael-like face turned to the man on a litter which had been placed on upended trunks. Plasma had already been attached to the man’s outstretched left arm – his face was shrunken and pallid under the dirt – by the time his pierced left elbow was in its sling, his opaque eyes were clearing and he was aware enough to grimace as his leg-splint was bandaged into place.[3]

But clearly film is not a medium that might convey this nor can it tell the story of fragmented lives in chapters for each of them. There is much you understand better if you have read the book, but do it, unlike me, after the film and then see the film again. There are aspects her multiplicity – even the bare facts thereof – that we miss, even though they might be referred to. Hence we only hear of her parents in passing, as of her apprenticeship and love life with Man Ray including his jealousy – a thing men who knew often became acquainted with, and her marriage and life in Egypt with Aziz Eloui Bey. We pick up her life only in 1937 where we have, if you don’t know them, to wonder at the identity of her friends – though the film helps by concentrating on Paul Eluard, the Surrealist poet, and his wife Nusch, gliding over Max Ernst and Michel Leiris. We start her life-story from her first meeting with Roland Penrose at a picnic:

The real Penrose, Eluard and Nusch in Miller’s photographs and the filmic telling of high-life in Paris before Miller leaves for London with Penrose abandoning Aziz in Egypt.

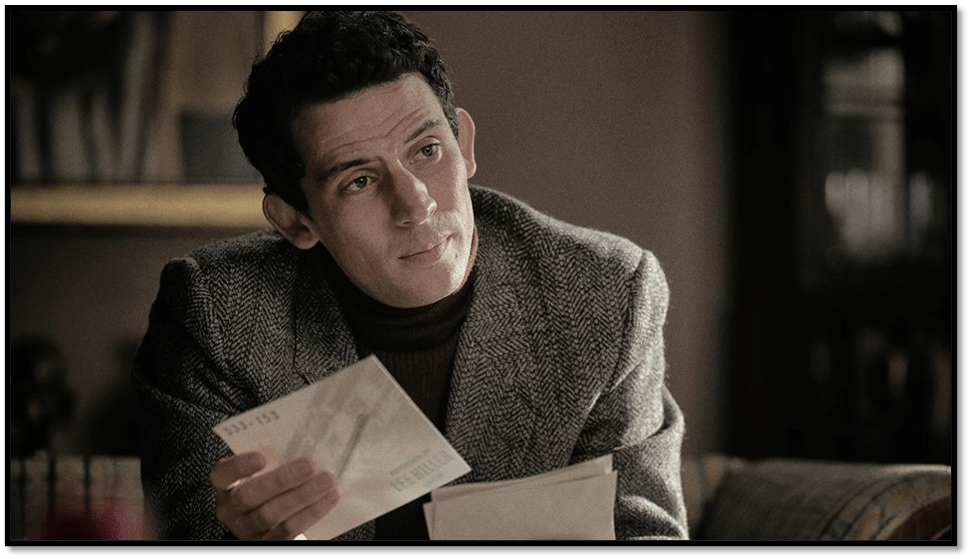

And we do not even get to that start except by the means of the ‘framing narrative referred to by Kermode. In the framing narrative, the elder Miller, brilliantly performed by Winslet who seems always to hold together the character through her often extreme variations, is interviewed by a young man, played by Josh O’Connor. This young man is only confirmed as ‘her son’, Tony Penrose, when she asks him to tell a story about his mother. It is a story that ‘disappoints’ her for Tony feels his mother has always made him feel in the way, a burden that stopped her life from being fulfilled, although Lee shows him documentary evidence (his first drawing and so on kept in a box) that this might not be the case. In fact the whole conversation may be something of a blind alley for both characters for reasons I do not want to state here. The justification for it comes from a postscript from Penrose’s book where he says that:

The Lee I discovered was very different from the one I had been embattled with for so many years, and I am left with the profound regret that I did not know her better. The regret is bound to be shared by many, as lee revealed only a small part of herself to any one person.[4]

O’Connor plays this mediator of Lee to us with a wondrous lightness of the same regrets as Tony. His eyes turn from the letter to recreate the person in his questing eyes.

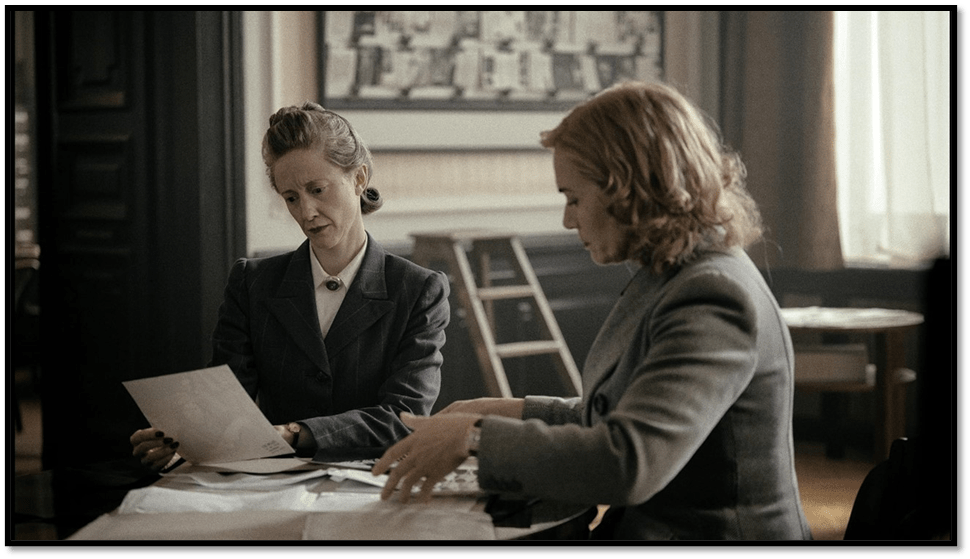

Moreover, Sarah Carson is surely wrong about the film’s commitment, a deep one, to a true feminism – one that does not trap women in the supposed ‘reality’ of biology. The politics of Vogue must have been complex for women and, like the book, the film is unswerving in demonstrating her loathing for Cecil Beaton, and why that was justified, though he too clearly plays a role trapped in gendered assumptions – brilliantly played with all the flounce intact by Samuel Barnett. Beaton’s posing was as earnestly class-bound as was British Vogue itself, but the wonderful Andrea Riseborough surely shows us the perfection of a woman navigating both class and gender barriers, as indeed as an actor she always does. Riseborough makes us love Audrey Withers of Vogue as much as Lee must have done, and is a useful corrective for why Withers put up with Beaton’s self-conscious entitlement n his male persona, despite the fact that much of his life undermined that persona. We see the quality of her aesthetic eye just through her subtle (almost Method-like) actorly looks.

Of other women this film makes brilliant use. Though a small role Marion Cotillard must rightly have jumped at the role of Solange D’Aven, Withers’ equivalent in French Vogue (known affectionately Tony tells using the book as Frogue). There is little meat in Penrose’s book on Solange with this exception about the role of Parisian couturiers under German occupation:

The leaders of some fashion houses were under deadly suspicion of having been collaborators; others, like Solange, whose husband was still a prisoner of the Nazis, were afraid of becoming too conspicuous for fear of reprisals against their loved ones.[5]

That is all there is in the book but the film brilliantly absorbs Solange into the theme treating the terrible double-bind in which Nazi occupation placed women in particular, using Lee’s tremendous pictures of shamed women to tell the story. Working and middle class women had their heads shaved by the Resistance leaders once back in power. The film picks out this historical detail to dive deep into questions of sex/gender and the role of ‘looks’ in the maintenance of female oppression. However, I won’t say a lot, for it is there to discover in this beautiful film so badly mis-viewed by Sarah Carson.

One of Lee Miller’s compassionate photographs of the shamed French collaborators. Lee Miller was virulently anti-Fascist, and for the rest of her life virulently anti-German -perhaps unfairly) but her understanding of women locked in love by men using the entitlement of their gender and the fact of Occupation was absolute. The film deals with this theme brilliantly.

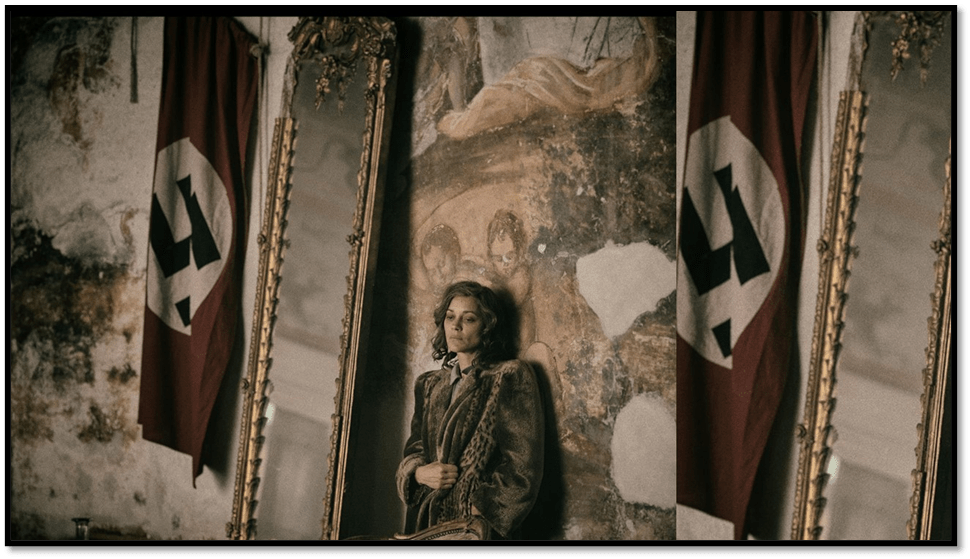

It is however this theme which makes Winslet and director, Ellen Kuras, so focus on a beautiful scene in which Cotillard as Solange steals the film momentarily. Lee tracks Solange to Frogue and in a room once the height of fashion but decorated by the swastika too, she finds Solange broken by her contradictions. Not shaved – women of her stature weren’t, but shamed and lost in reverie about the fate of Jean (whom the film shows us later to have survived and Solange goes back to a conspicuous limelight which caused her danger in the past). Solange is not an exceptional woman like Lee but her situation needs understanding by true feminists – and this film does that. Look at this beautiful still in which the art décor of Vogue offices, mixing the swastika with Baroque art frescoes , makes us see Solange’s shame as if a thing created from mirrored and reflected appearances. Only Cotillard could have played this bit-part so well.

As for Lee, like Civil War, this film equates her with the framing of photographs, as in the still below. The camera that hangs at her midriff becomes a tool and a weapon that she learned to use in moments of great tragedy with trepidation, at first, for her intrusion, but one she will use with great boldness in her pictures later of the piled-up dead from the ‘liberated’ concentration camp of Dachau – here she is picturing a group of displaced orphans and mothers in post-war Germany, staring (she follows their carer through the streets as she arms herself with bread from the Allied occupiers) out frightenedly, letting the eye of her camera do the dirty work for her of framing misery whilst feeling the scene in her eyes.

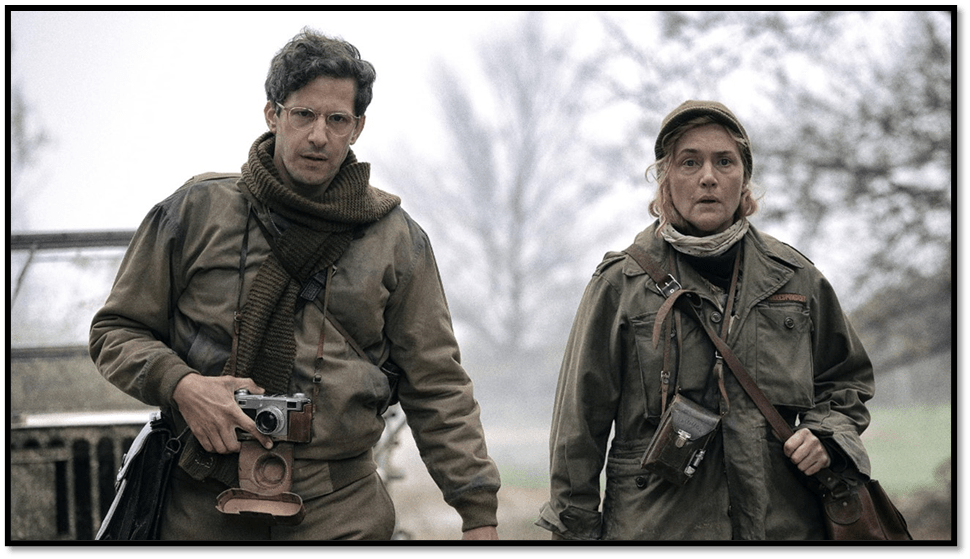

And the role of David Scherman, an American Jew who only belatedly learns he identifies with the fate of those in Germany is crucial, having sometimes still to ‘lend’ to Lee the entitlement that his sex/gender gives him (‘you are only able to go to war because you have balls’, the disgruntled Miller says to him in bed, lusting for ‘adventure in the most knight in shining armour way). He lends entitlement to her by getting her into places that women are not allowed. He lends it to her when she eventually realises that she and David must relearn responses labelled ‘feminised’ by patriarchy. I find the still below intensely moving, where Lee realises she has not yet learned to cope facially with the perception of the horror of war.

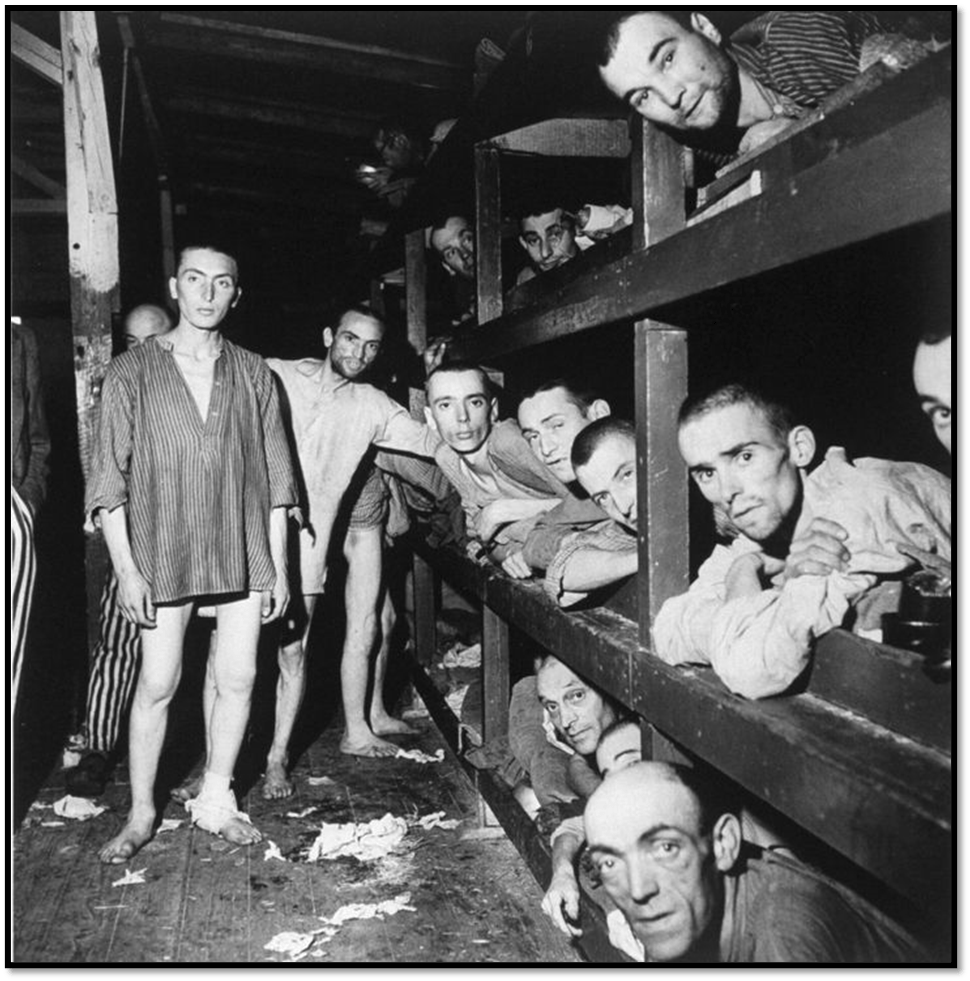

An yet, she registered these at Buchenwald (there are worse – the film forces you to linger on them often, even of piled corpses which were there because the camp’s ‘crematorium’ had run out of fuel):

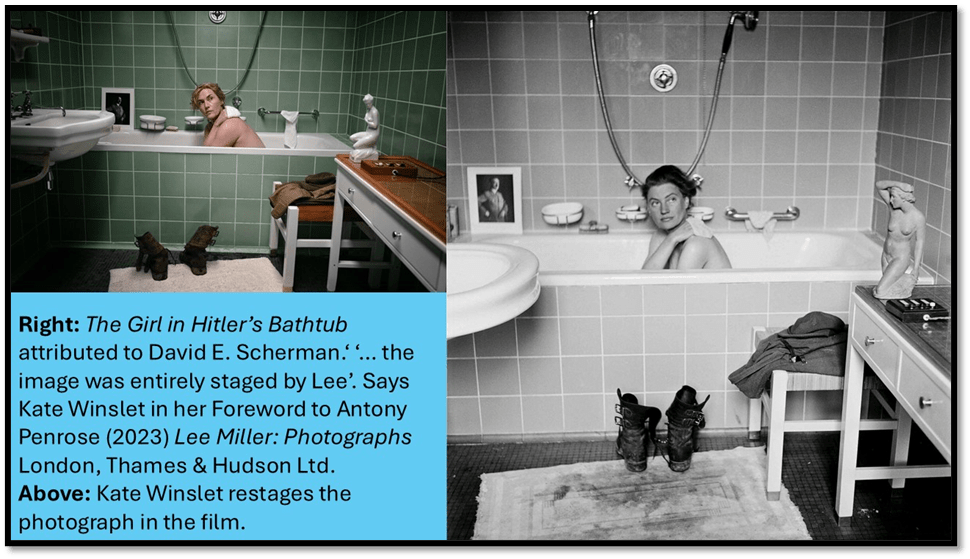

Lee’s trivial collector instinct comes through for this is a honest film. Penrose notes that when Lee got entry into Hitler’s chalet home (it seems transferred to a city street in the film), she and Dave took complementary nude photos of each other in Hitler’s bath, although only the nude of her was published (another way in which appearance trapped women). What also happened is that each took souvenirs:

Dave took the complete works of Shakespeare in translation with Hitler’s bookplate on the flyleaf, and Lee left with a large ornate silver tray with the A.H. swastika monogram stamped in it. This later became the drinks tray in her London home.[6]

The film neglects the Shakespeare and Dave, as with his nude photo taken by Lee, but subtly embeds that tray in the film. It is used in the home by a G.I who serves them both with whiskies. We see the monogram hold the screen if we are ‘noticers’. No-one talks about it. We see it though again, again if our eyes are open, used in a party in the Penrose London home after the war and amongst her memorabilia but not discoursed upon. This is what tells me that the film is meant for noticers not Sarah Carson.

And the bath picture. Winslet in the Foreword to Penrose’s book of Miller’s Photographs points out its title The Girl in Hitler’s Bathtub is hardly appropriate, but then neither was Lee she felt appropriateness was an oppressor. She wanted it to be meaningful even if it got into publication because she hid her breasts while still tantalising with their possible appearance, because she placed an eighteenth century female nude (a pastiche of the nude male classical) by the bath to point up that appearances were a source of evil in Nazism. Just as she propped up a picture of Hitler.[7]

But the film also tries to show us the complex desire for nuance in her as a writer, not just when Roland asks Audrey not to send her more writing commissions because of the stress it causes her, but in the constant recall of her with a typewriter at which she bangs. Though the image is not used, it recalls Remington Silent from Grim Glory (see it below).

Lee knew what it was to be silenced and effectively she still is – for no-one takes Vogue that seriously in the history of literary prose. This prose piece accompanies a photograph of the same baby, but the prose! It is horrific but beautiful in its horror – necessary as a compliance and appropriateness shaker-up, for it mimes the colour description of costume in Vogue.

For an hour I watched a baby die, he was dark blue when I first saw him. He was the dark dusty blue of these waltz-filled Vienna nights, the same colour as the striped garb of the Dachau skeletons, the same imaginary blue as Strauss’ Danube. I’d thought all babies looked alike, but that was healthy babies; there are many faces for the dying. This wasn’t a two-month baby, he was a skinny gladiator. He gasped and fought and struggled for life, and a doctor and a nun and I just stood there and watched. There was nothing to do.[8]

There isn’t much more I can say, for the film demands watching. However to accuse it of failing feminist analysis is grotesque as its fine assemblage of women in control of its art shows, though the men collaborate beautifully. You must see it – but really SEE it. Don’t leave the connection between eye and brain behind for in that belongs its beauty.

With Love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] Sarah Carson (2024) ’Sorry Kate Winslet, this boring biopic feels like a Wikipedia page’ in the i newspaper Text available at: https://www.msn.com/en-us/entertainment/news/lee-review-sorry-kate-winslet-this-boring-biopic-feels-like-a-wikipedia-page/ar-AA1quMpf?ocid=BingNewsSerp

[2] For Field Masks see Antony Penrose Lee Miller: Photographs (2023:35) London, Thames & Hudson

[3] Antony Penrose (2021: 166 – compact pbk ed., originally hbk publ. 1988) The Lives of Lee Miller London, Thames & Hudson

[4] Penrose 2021 op. cit: 326

[5] Ibid: 177

[6] Ibid: 190f.

[7] Kate Winslet ‘Foreword’ in Antony Penrose (2023: 7f.) Lee Miller: Photographs London, Thames & Hudson Ltd. 7–8.

[8] Penrose 2021 op.cit: 217

One thought on “A great film worthy of the inimitable Lee Miller: ‘Lee’ seen on Tuesday 17th September 2024.”