Geoff and I went to York last weekend.

Preview of blog theme: As I watched The Critic, I wondered how or why it was legitimate for characters in it, like Jimmy Erskine, who thinks being in a painting might do it, to desire immortality. Angie Han of The Hollywood Reporter obviously saw this too for she says for she sees them doing so in a world where there is strong evidence of the ‘the encroaching reach of fascism’ which adds a sense of danger that draws ‘pointed parallels to our own troubled times’. In the face of such ‘world-destroying potential’ she insists that the ‘characters’ frequently stated longings for immortality — in the form of a painting, a dynasty, a legendary career — seems not just misguided but futile’.[1] But perhaps that theme, alongside with that of demonstrating one’s personal power to change the world, is there to manifest a larger theme: that of the futility of either art or the command of a press dynasty itself to pretend to elevate the nation.

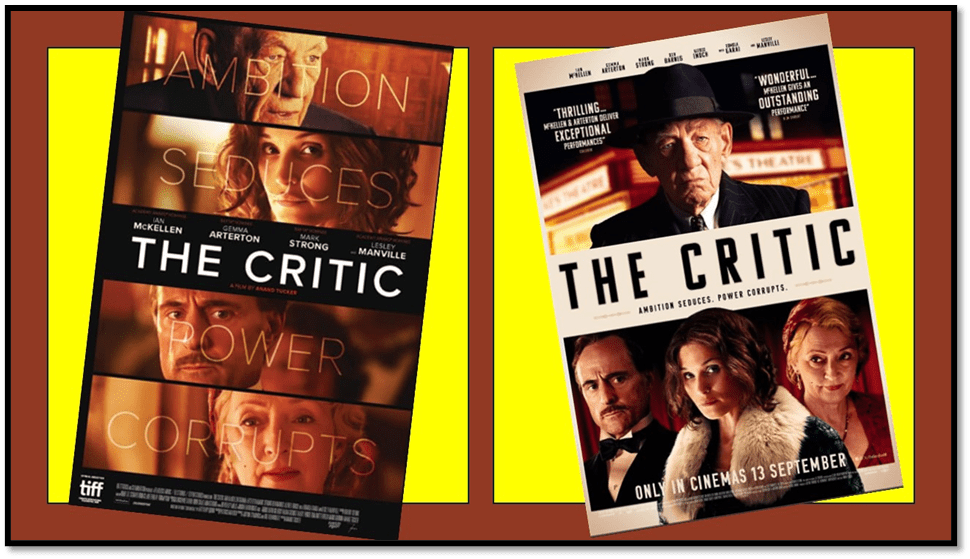

This blog is on The Critic (in cinemas now).

Let’s start with the bad news, for I saw this film in York with my husband, before reading or consulting any reviews. We both enjoyed it for its rather jaunty narrative where the wicked behaviour of a proud man is punished and his machinations foiled, if at the cost of the life of his unwilling accomplice. The Critic has been so savaged by film critics that there is poignancy in Clarisse Loughrey in The Independent defending herself and her colleagues by saying that, unlike the 1930s when the film’s story is set no art critics now ‘hold the same power or respect as they once did’ and therefore she and her colleagues can’t be accused of bias is about the worst behaviour imaginable, and not only in his reviews, being exampled in theatre critic, Jimmy Erskine (played by Ian McKellen).[2] However other critics tend to say that the acting is good, except for Loughrey who says there is not much to the film but ‘plain melodrama’ and even the best acting in melodrama hardly calls for subtlety. Dan Rubins in Slant Magazine also sees the whole thing as ‘trembling melodrama’ rather than intelligent in the way the best of almost any other genre can be, even the rollicking death gluts of Jacobean tragedy.[3]

However, he thinks no ‘connections are drawn between’ such ‘genre pieces that Jimmy attends and his own unscrupulous activities’. I beg to differ for Lands’ unknown lover, David Brookes, the heir to the right-wing newspaper institution that is named The Daily Chronicle, sees her in The White Devil and sobs inwardly at her death in the role of Vittoria Corombona, a courtesan. Perhaps we ought to remember that Lands resistance to act the role Erskine wants her to play is met by her saying: ‘I am not a prostitute’ (not that is Corombona). The Land family know very little about drama after all. Erskine is right of course to put Mrs Lands right when she clumps Christopher Marlowe with John Webster, insisting it matters the former was Jacobean, the latter Elizabethan. The moment of Brooke watching the stage death of Miss Lands’ Corombona is, as yet unbeknownst to us, predictive. The parallel is thin but then so is that of the power structures of the Renaissance courts of the Italian princes imagined by Webster with press barons of the 1930s, though the parallel is there. Is not the Brooke newspaper dynasty not unlike that of Lord Beaverbrook?

Angie Han, like most other critics (except Loughrey who says McKellen merely ‘luxuriates’ in his bitchy role) excepts Ian McKellen from a critique of the thinness of the acting expected by this piece, though also saying that McKellen, presumably and by implication, puts the rest of the cast in a dark shade around the bright lamp of his capabilities: ‘That McKellen makes his rare flashes of sincerity convincing only renders the emptiness we see the rest of the time more disturbing’.[4]

To be fair though, in the main the attack om the film is not on actors, as Jimmy Erskine’s is on Nina Land, played by Gemma Atherton, whatever she plays in the theatre, but on the non-acting creative crew– its direction under Anand Tucker, its screenplay in particular by Patrick Marber and even, by Loughrey again, the cinematographer, David Higgs, for ‘turning London into a fog-choked proscenium, never quite real in its existence’. In fact, while Loughrey is on a roll, she even blames her predecessor film critic at The Independent, David Quinn, who wrote the novel Curtain Call on which the film is based, although indirectly by showing how its extant theme about the social power of cultural criticism, for it is a story in which there is not the ‘substance’ she expects. Dan Rubins in Slant says the novel itself has a ‘haywire plot’, even if he finds McKellen a ‘wicked delight’. Wendy Ide of The Guardian, who always has her ear to the ground in the film industry says:

This adaptation of Anthony Quinn’s 2015 novel Curtain Call, with Patrick Marber as screenwriter and Anand Tucker (Hilary and Jackie) directing, should be lurid fun….. But despite reported reshoots and a fresh edit after the film’s coolly received premiere last year, its sour spirit and a cluttered, clumsy third act remain a problem.[5]

I suppose Loughrey has a point about substance in terms of the novel’s realisation as a film failure to address the racism against Jimmy’s black younger lover that it merely toys with. It does the same you might think, but no more than any noir thriller with the heavily gendered violence throughout.

I suppose I have to be honest in that I saw this film mainly as a kind of ‘noir’ spoof and rather enjoyed its exaggerated stereotypes, though their implications are horrific if you work them out. This could be just fun. But then there were these hints at something serious. At the film’s heart is a kind of Basil Hallward, a married man named Stephen Wyley (played by Ben Brandes) whose father-in-law is David Brooke. He has a secret longing too, like his father-in-law, with Nina Land (Gemma Atherton) but because of his connection to Brooke must drop Erskine from the group portrait he was painting. This painting Erskine had joked would give him ‘immortality’. The role of Basil Hallward in the picture of Dorian Gray is to give the eponymous protagonist immortality, but he will give it in a form that turns into a nightmare.

Hallward shows Wotton his portrait of Dorian Gray, that will make his youth continue living.

On the edges of the motivation of artists the endurance of a name and of some beauty that have or have created is a version of immortality and this is pursued by Erskine, even if with a hint of irony at himself. Later he speaks of having lacked the beauty that would have attracted Oscar Wilde or the closeted queer artist Henry James. Wilde, he says, walked by him at a theatre door without looking twice because he lacked that kind of beauty attractive to him. The love of immortality drives Nina Lands, mainly through the inspiration of a younger Erskine she will reveal. It drives the Brooke newspaper empire and it dives Stephen Wyley.

Wyley and Lands lying on the floor with Wyley’s art around them

Immortality is achieved by shadowy people’ in this film, who write the plays all of these characters watch or talk about – Webster and Shakespeare – or paint lasting pictures or newspaper industries that pretend to be enduring. Actresses seek the immortality of the parts they play. In my title I say that, as I watched The Critic, I wondered how or why it was legitimate for characters in it, like Jimmy Erskine, who thinks being in a painting might do it, to desire immortality.

Angie Han of The Hollywood Reporter obviously saw this too for she says for she sees them doing so in a world where there is strong evidence of the ‘the encroaching reach of fascism’ which adds a sense of danger that draws ‘pointed parallels to our own troubled times’. In the face of such ‘world-destroying potential’ she insists that the ‘characters’ frequently stated longings for immortality — in the form of a painting, a dynasty, a legendary career — seems not just misguided but futile’. Butas I reflected, because I had liked the film, I took Han’s statement a bit further, for if indeed it is obviously futile to seek futile in the world of this film, is not futility itself a theme. For if so, what we watch is people who have no chance of immortality, who are in a world so exaggerated that an audience of today losses any sense of it ever having reality because the temporal duration of that world is so well known to us. It is as if we see characters as puppets playing out scenes where they cannot hope ever to matter in a significant way to anyone, even themselves.

What strikes me in the film is that McKellen’s Erskine is at his most vulnerable when his queerness is challenged, and its rights (to love or meaning) degraded even by his cruising and cottaging. The park cruising and cottaging scenes are the most unreal and dream-like of all the scenes, the bit of ‘rough’ he desires even seems to dress like a ‘pearly king’ of Cockney mythology. There is just humour in the way Erskine and the working-class man he picks up peer over the bushes to see young men solicit in in the park being arrested by police. This is a world of pure contingent luck, where it futile to expect anything much else. But the same goes for Nina, Stephen and Nina’s aspirant mother (played by Lesley Manville). The acting we see is wooden at best and so is Stephen’s art, especially that of The Daily Chronicle ‘greats’.

In my view the film deliberately places events in lurid lighting that obscures. The three ‘old guard’ from The Chronicle are all closeted queen. As they sit in their club, it seems like everyone’s stereotype of a brothel in its lighting.

Far from immortality, even Erskine luxuriates in decay of everything that gives him meaning. We see him so often in the bath, almost melting into insignificance, neither beautiful nor truly reflective – just flashy like his prose and his jokes.

When Lands dines with David Brookes, they dine in the parody of grandeur neither of them believes in but puts up with for the other – hoping its look will fool them about the reality of what they offer each other.

Han is brilliantly right about the world of the film being one where the pretence of greatness – in Brookes father who has a Union Jack on his coffin at his funeral – lay in pompous idiots who saw themselves as significant but whom were soon rightly forgotten. Their greatness was boorish arrogance, as Erskine’s is. Of the young Brooke taking over from his father, we hear:

Where his father prioritized “strong opinions, strongly expressed,” the younger Brooke has other ideas. His Chronicle intends to dial down support of British fascism, and reposition itself as a family newspaper — one with little tolerance for what Jimmy’s editors delicately term his “proclivities,” which is to say the open secret of his homosexuality.

Everything is being repressed in the new world, even the fascistic implications of some lifes and replaced by the brutish with no pretensions – especially in an world so anti queer. But note too, that though the critics keep saying Erskine’s prose is wonderful wit and beauty, he is no Oscar Wilde anymore than he could attract Oscar Wilde. He certainly could not now. His lover – beautiful man indeed – puffs up Erskine’s sense of the beauty of his prose and insights even when it lacks either. I do not think we are meant to admire the following prose, even though everyone acts as if we should, even though they might find it shocking. Even antagonistic critics of the film like this piece on Lands’ death as Corombona in The White Devil: “when Miss Land finally, blessedly, expires, her death is akin to a deflated dirigible.” This prose is execrable NOT BECAUSE IT IS SHOCKING but because it is merely an outward show of a metaphor that never helps us see why she is a bad actress. Similarly, is Erskin’s lover really admiring prose that uses the term ‘“steatopygous, which he later replaces with the literal ‘fat-arsed’. Dan Rubin thinks the filmmakers want to see wit here but I don’t think so. We see mere futile attempts at showing off, for this is the world of the film for everybody in it, even the working class rent boys.

Critics are right to see the characters as pursuing aims that are nothing but demonstrations of the futility of human desires and aspirations for things that are solid. This is why I think McKellen’s moments of seeing through such showy stuff matter – when, for instance Brooke tells him to ‘tone it down’, he realises the emptiness anyway of what he is – perhaps he always knew. His look seems to say so.

Gemma Atherton was given an impossible part to play – an actress that cannot act and is only good when she does ‘less’ as Erskine advises her and whom is at her best only when drunk as Erskine says finally of her and after her death, no longer then trying to hurt her. But, in my view she plays the role brilliantly whilst being aware that when she does so people will see her acting as lacking in comparison to McKellen or see her as let down by the script. In fact I consider her as brilliant. She returns to water in her real drowning in a bath and the pretend one in the Thames because that sis when this woman is best at life – when returned to the fluid and unstable. Her role captures futility better than any other – her acting is masterful. Her pretence at control is the best acting she does (with Brooke).

But her great achievement is in her disintegration into vapid beauty. Great beauty but with a pouting quality that is as great as futile greatness can be.

I liked the film. I could see it again.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Angie Han (2024) ‘‘The Critic’ Review: A Ferocious Ian McKellen Is Let Down by a Script Favoring Histrionics Over Depth’ in The Hollywood Reporter (online) [September 15, 2023 9:15am] Available at: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-reviews/the-critic-review-ian-mckellen-1235574990/

[2] Clarisse Loughrey (2024) ‘Ian McKellen is too good for this overstuffed theatre critic drama’ in The Independent (Sept. 2024) text available at: https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/uknews/the-critic-review-ian-mckellen-is-too-good-for-this-overstuffed-theatre-critic-drama/ar-AA1qsGV3?ocid=BingNewsSerp

[3] Dan Rubins (2024) ‘The Critic Review: Ian McKellen Is Brilliantly Acerbic in Anand Tucker’s Flimsy Thriller’ In Slant Magazine (online) [September 11, 2024] available at: https://www.slantmagazine.com/film/the-critic-review-ian-mckellen/

[4] Angie Han (2024) ‘‘The Critic’ Review: A Ferocious Ian McKellen Is Let Down by a Script Favoring Histrionics Over Depth’ in The Hollywood Reporter (online) [September 15, 2023 9:15am] Available at: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-reviews/the-critic-review-ian-mckellen-1235574990/

[5] Wendy Ide (2024) ‘deliciously waspish Ian McKellen lifts 30s London murder mystery’ in The Observer (Sunday 15 September 2024) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/sep/15/the-critic-review-ian-mckellen-gemma-arterton-patrick-marber-anthony-quinn-curtain-call-adaptation