‘Action Man / takes the measure / of the enemy, // or perhaps / he’s back home / pegging out nappies // wondering, / what has he been / reduced to’.[1] What is the role of poetry in mourning and celebrating the political past. This is a blog on Sarah Wimbush (2024) Strike York, Stairwell Books.

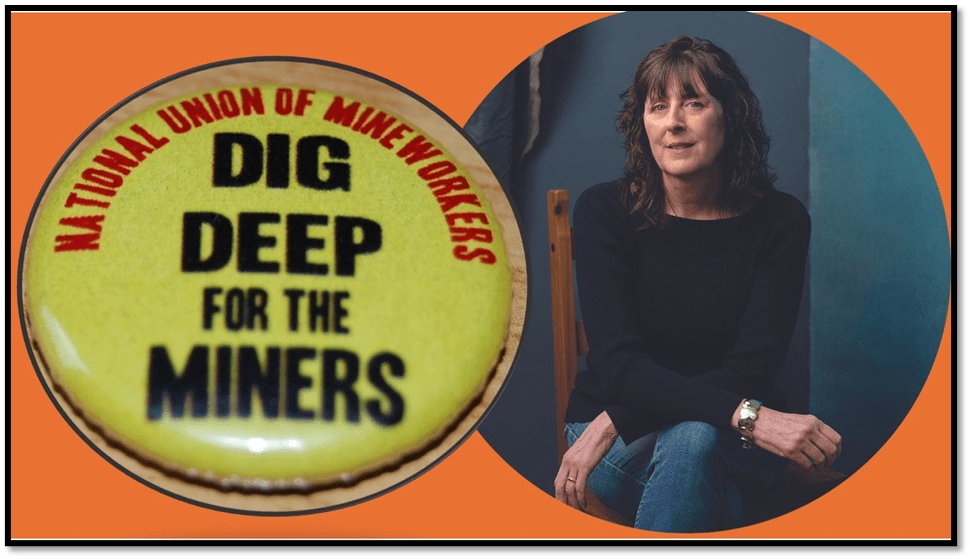

It is difficult to find reviews of this book in that part of the national press that claims to take literature seriously, and if I were generous in my judgement of that I would say it is because it is so hard to say how we should, or can, evaluate as poetry, art that strikes at meanings and feelings, even visceral senses, close to our passions over the whole course of the shifts in culture that occurred in the 1980s. That was my position – among these poems I find prompts to tears – some of joy actually – and memories of involvement with Gays and Lesbians For The Miners, who feature in poems here, as well as the importance all this had to my strong sense of working-class identity then. I remember the badges, the marches, the hatred of Thatcher, ambiguity about Neil Kinnock and doubts about Scargill’s capacity for the role he had, and difficulties about outlying violence against individual working miners – all of which show up in the poems. But the great memory is of unity against mechanisms that showed themselves as they were – oppressive and representing oppressors.

Hence in one review, to which I’ll return by Steve Whittaker in The Yorkshire Times (online) I bridled at what felt like an apology for Sarah Wimbush’s partisanship on behalf of miners. As I look back now, not to be partisan was to be aligned with dark forces, and I will before returning to Whittaker, look at people who are still obviously like me THEN, and to some extent now, writing about these poems from a committed left self-positioning:

Sarah Wimbush’s alignment with the miners, and their cause, is never less than partisan. In her latest collection of themed poems, as in her wider poetic oeuvre, that sense of affiliation is front and centre, indissolubly bound up with the connective tissue of her South Yorkshire roots.[2]

But all three reviews I did find are warm and cheering, None of them guide me and I take my own path with these poems but want to explain why first.

In an online ‘independent international literary magazine called Tears in the Fence Rupert Loydell sees Strike as an attempt to reclaim an interpretation of the time of the Miners’ Strike of 1984/5 and resurrect its political attitude for change for the many in society based on views of history untainted by neoliberalism. The latter is I suppose a view of history that I suppose discounts the notion of class for a view of individuals in competition for resources and control based on their own talents. It, neoliberals might say, is a world where all are free to try for the glittering prizes available in society but which only few attain, These are, Loydell claims using this book, ‘Lies, Lies and more bollocks’ . In the poems he finds a reminder that the many must act together against a society serving the interests of a few and help in doing so by a ‘passionate, engaged retelling of recent history’. But as passionately as I support Loydell’s view I cannot agree that he points to the strengths of the book of poems and photographic pictures from many sources which he sees as ‘full of the complex personal lives of the time’. [3] For of complex analysis of personal lives there is little – rather there is an attempt to see beneath appearances to how the people felt in simple broad-brushstroke terms and invite the reader to see value in these feelings and thoughts – not as a stated political programme or view but of a comprehensive appreciation of the values that make human life sustainable for all.

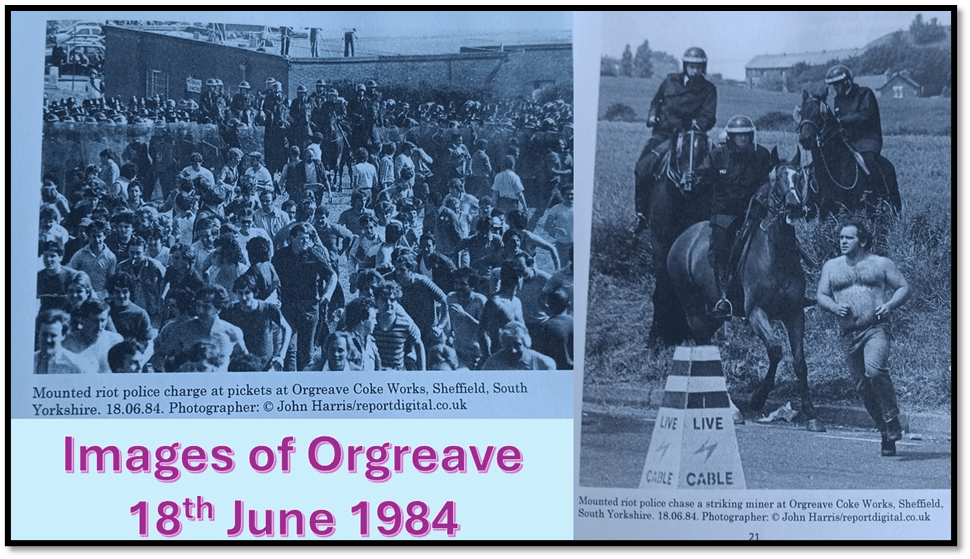

There is a somewhat similar starting point for the review in the left online magazine Culture Matters by William Hershaw. He spends considerable time outlining a left-oriented history of the period, correcting the fact that history is ‘is written by the victors’ of any political struggle. Himself from a Fife mining family he compares the vision his family on the ‘coal-face’ of the contest had with what was a ‘tightly controlled’ view of events on the media, where there were no mass alternatives like social media. In his view the poems are strong in backing such a view, especially a belief that the BBC was part of a conspiracy of silence about the justice of the miners’ cause, that even went as far as explain the way the BBC did indeed as a historical fact that they now admit (but didn’t at the time) reverse the footage of the conflict at Orgreave Colliery so that it looked as if the police were responding to thuggish violence from the miners rather than the other way around. Hence he treats Wimbush’s This is the BBC poem as a factual correction of what happened at Orgreave with the purpose of what it felt like to be one of the miners there: ‘In This is the BBC we are given a sense of what it is like to be victimized and ambushed while all the while being presented as the one to blame:

Record. Rewind. Reverse.

We walk through open gates,

A thud of hooves behind us.’[4]

Pictures each accompanied by its poem, which interprets the picture in the book. Wimbush, op.cit: 19 & 21 respectively (‘This is the BBC’ ibid: 18, ‘Miner running towards a field at Orgreave’ ibid: 20).

Whilst Loydell talks about these images, saying that ‘images of police in riot gear, assaulting unarmed workers exercising their right to strike and picket, will not go away’. He says further that many ‘of these images’ appear in the book, ‘along with celebratory, elegiac, assertive and political poems’. Hershaw goes further. The relationship of each poem to one of each images picture is asserted as giving ‘an important published piece of testimony – an accurate witness account providing evidence from pen and camera, a scrupulous forensic inquiry and work of art, put together through the lens of hindsight and poetry’. It leaves a lot of questions this description with its insistence on the language of the criminal law (almost reversing the position of government and workers at the time, wherein defence of the rule of law was the Government’s stated priority in their defence of police actions). Nevertheless, Hershaw interprets the relationship of poem and photographic precisely right: ‘Accompanying each photograph is a poem; an interpretation of the meaning and significance of the adjacent image’.

But I think he goes astray in locating them as accounts of ‘forensic evidence’. This is because the science of witness testimony, well developed in forensic psychology, can offer no succour to either side who use arguments asserting they saw things totally correctly and that other side saw them totally falsely. The science of witness testimony emphasises that such testimony is open to all kinds of situational and cognitive circumstances that skew any attempt to equate what we see with what is happening or did happen in any circumstance. This is the case for any account from any source and binaries of positioning between truth on the left and lies on the right (or vice versa – which happens more often for ultimately the right own the organs of the media) rarely move the debate onwards. Of course, the manipulations of just these situational and cognitive factors were evident in the BBC at Orgreave in June 1984 as they admitted in 1991 (7+ years after the event). Wimbush quotes them in an endnote to This is the BBC in her volume: ‘The BBC acknowledged … that it made a mistake over the sequence of events at Orgreave… it was a mistake made iun the haste of putting the news together. …the editor inadvertently reversed the occurrence of the actions of the police and the pickets’.[5]

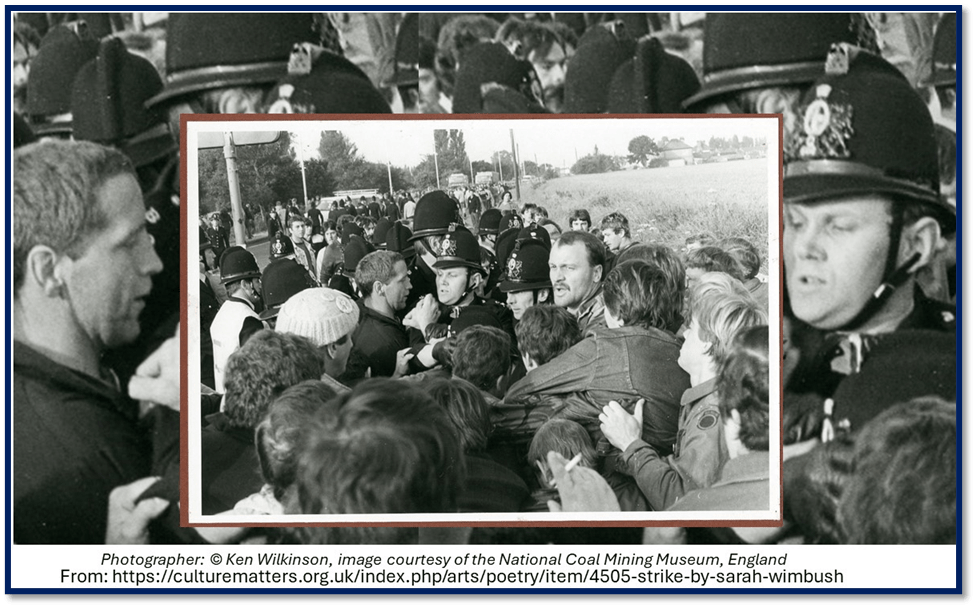

Hershaw’s account provides another image that merely cements the points I make in the last paragraph. Here the camera records a miner confronting a young policeman. At first sight the miner looks aggressive as oft Arthur Scargill did. Like the miner Scargill talked to people – in public but some say in private too – with his up and down wagging finger pointing at his conversant(s). One Wimbush poem nearly says that Scargill was often over-confrontational in approach as he used raising ‘his iambic voice, that finger’ so much.[6] An iamb is the name in metrical verse for a two syllable unit called ’a foot’ in the metrics of poetry – whereof the first syllable is less stressed than the second – which I embolden in my example: Thomas Gray uses five iambs (the line is called an iambic pentameter) in the first line of his Elegy in A Country Churchyard: ‘The cur/few tolls/ the knell/ of part/ing day’. Scargill beat the iambic measure of his rhetorical language (that often forms naturally into iambs) with his finger – hence the blur in the photograph. Many men did in those days, without intention of violence.

The stray-dog-kids are coming, he says, raises his iambic voice, that finger’.

Note how accurately the verse interprets the detail of the photograph. It is how the poems work.

But let us look at the photograph Hershaw provides that is not in the book. It is below. See the miner with finger raised to the policeman, who looks young, inexperienced and frankly frightened by the position Thatcher’s orders have put him in. The miner is apparently pushing against the policeman. But that is perhaps an illusion of the fact that the miner is being pushed from the back by other policeman. In the background detail shots to the picture I separate young policeman from the miner and obscure the pointed finger. Yes the policeman is still literally ‘s…t scared’ but look at the enlarged face of the miner. Any anger we interpreted in it has disappeared. He is smiling not scowling and there is a softness to the face that we, full of stereotypes of how working men are, thought we saw when the detail was harder to interpret.

A picture surrounded by a thin blue line – but for the people at Orgreave that line was thick. Very thick indeed, its strings pulled by Margaret Thatcher

This may seem irrelevant but I think it is not. I think we need to see that without losing partisanship to mining families her aim is not just to ‘combine’ word and image but to use words to describe as well as words can what she sees, and how she interprets what she sees, in each photograph. This is a very old skill in poetry indeed and is described by the Greek-derived term ekphrasis.[7] That Wimbush does not betray the learning implied in the origin of her chosen genre of writing has a lot to do with the determination not to alienate her readership of working men, not all of whom have had even the chance of an entitled education of an extended kind, and less so of the poetic tradition, though it was not always thus, as Edith Hall & Henry Stead (2020), in A People’s History of Classics: Class and Greco-Roman Antiquity in Britain and Ireland 1689 to 1939,brilliantly tell us (see my blog on this book here).

The more I read Hershaw’s account however, the more tugged I feel. He understands the mode of these poems without having to mention ekphrasis as I do. However, his understanding strays in my view in thinking everything in the poems takes us back to a direct and unnuanced political position. Look at this comment:

I began this review with a cliche, so here’s another: L.P. Hartley wrote that “the past is a foreign country”. I thank Sarah Wimbush for providing me with a passport and a means of transport even if the destination I arrived at was depressingly similar to the one I live in now. 40 years down the depressing line Britain is like a rudderless boat in the North Sea. A country of inequality and disunity, of foodbanks, homelessness, drugs, anti-union/freedom legislation. If this is what Thatcher meant by “trickle-down economics” then well done…

But I think he needs the rest of the famous L.P. Hartley cliché quotation, from The Go-Between:

For many of the poems work not by telling us that neoliberalism is the same now as it was then. It is, in fact, but now feels emboldened and about to take victory, creating for instance the conditions of a ‘changed Labour Party’ that tells us that universal welfare rights is a potential drag on economic growth and trickle down wealth expansion. It has changed us all and we can’t fight it in the same ways. If we try to understand 1984-5, we have to understand not the political positioning but the values implied in the behaviour exhibited, for all it means. Hence I defend my use of ekphrasis – for it helps to show how Wimbush uses a traditional form of poetry to make us see better the people and the values that matter in behaviour, and what we see is never binary, though people call the perspective we use in our interpretations ‘partisan’, like Whittaker. He says: ‘Strike’s earnest commemoration, in poems and pictures, of a time of cataclysmic change, is as persuasively distilled as a polemic’.[8] But the phrase ‘as a polemic’ is a problematic one. Whittaker wants us to see the poetry as polemical without saying so directly. There is a negative association to the term ‘polemic’ that there is not to the term ‘description’ or ‘discussion’. But if we learn always to treat the poems as ekphrastic we look only for their ability to help us see what is in the photographs.

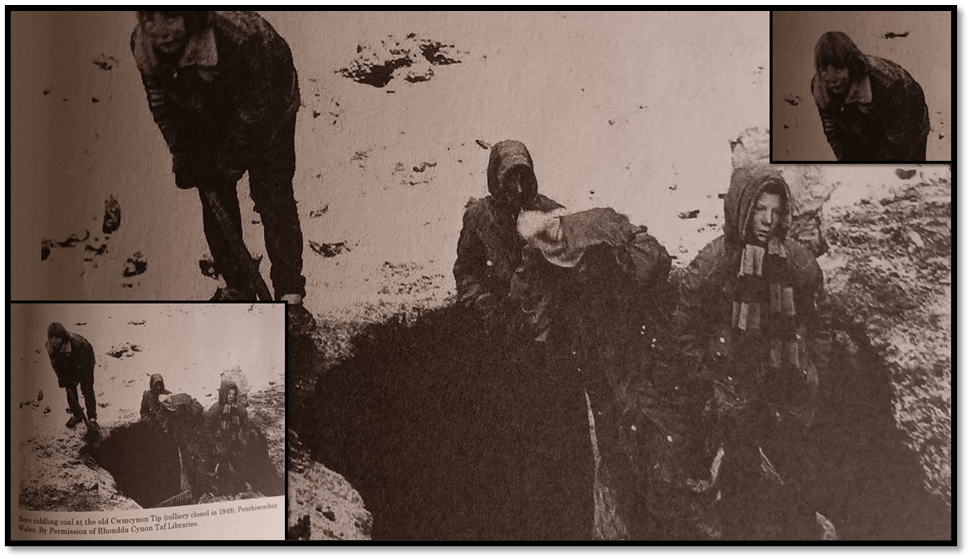

I want to take an example that is clearly not set in a scene of binary confrontation though many are not in the fact of it. Here is the photograph for the beautiful poem Boy Riddlers.[9]

The poem and photograph are in Wimbush op.cit: 62f.

Here is the poem:

No wooden sled or carrot for a nose only soggy ears in a frozen maw. Junior excavators, waist deep in the whiteout on Cwmcynon tip, flattened after Aberfan. Snood-face and lads-lost numb In Woolworth anoraks; spade-boy, hoar-eyed and black-blushered digging for Penrhiwceiber. Spoil riddled through a shopping basket, then topping-up the spud sack with alchemies of compression dripping through their hands.

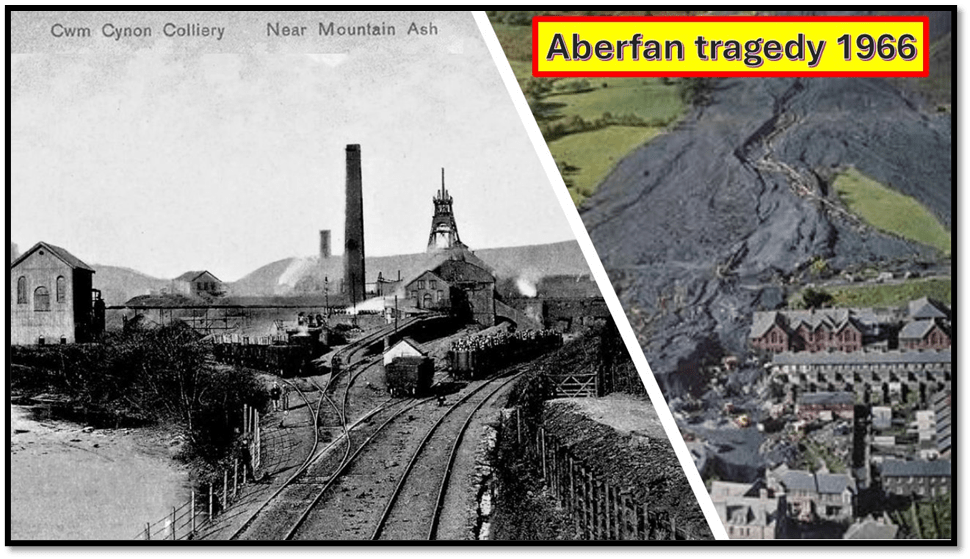

Penrhiwceiber is geographically precise enough and other photographs and poems show the life of this pit, as once was, and its associated community in a ‘foreign country’, though ‘they do things differently there. Not because it is Wales but because it is a mining community in the 198s that is washed out of the Wikipedia link to which I referred you. Everything in the name Cwncynon speaks of the past – a colliery, a tip that is all that remains of a slack heap of rejected coal materials, that buried children at primary school in Aberfan in 1966 (only eighteen years before the strike). The tip is commemorated now in an archive of photographs of children collecting coal, And see how this bit of coal ‘slack’ like the words here is the equivalent geologically of the compression (and oppression) of history. And yet the value of our history and its resources is ‘dripping’ through the hands of boys who riddle. The world is at fault here. There is something of greater need of ekphrasis in this photograph which is a ‘black hole’ in the middle of a ‘whiteout, the tip covered with snow.

Though the activity is riddling coal through something that stands in for a sieve (a ‘shopping-basket) to collect only the biggest nuggets of burnable coal, the sense in which riddles means someone who tells a ‘riddle’ that must be solved is also present, as we gather the clues that picture a snowman without actually naming one, as riddles do. Relying as riddles do on double meanings the ‘frozen maw’ relates to the open moth of the boy on the left and the snow-surrounded hole penetrating the black remains of the flattened tip. The poem interprets but only by suggestion the expression of all the boys in complex metaphoric adjectival phrases built entirely of nouns or a noun and an adjective in reverse order to emphasise the loss of childhood (ladhood): ‘’Snood-face and lads-lost’ to further modify the adjective ‘numb’. However, many kinds of numbness are indicated here – numbness to ideologies of warm protected childhood, of lad-play free of the burden of adult work.

They dig not only through ‘spoil’ (a term for the contents of a tip in the mining industry) but are themselves unearthed ‘spoiled’, spoiled by the maw of the pit-system that kept their fathers in holes in the ground, black holes like The Black Hole poem that follows this one in the poem and shows the hollowness of the miner’s pride in ‘this Welfare Hall’, which will be, when the miners voting to return to work ‘with no agreement’ ‘full with empty spaces’, as will many hearts. There is there most brilliant poetic move in this latter poem:

when there is only the stroke

of a muffled drum,

we will bear our white eyes

and grey faces –

the ground rushing to meet us,

windows blown apart by the sun.[10]

Of course the last metaphors are wonderful but so is the dulled assonance of ‘stroke’ with ‘strike’, together with the fact that a ‘stroke’ will be, and has been the fate of many older miners ‘struck’ (the genuine past tense of being passively stricken) by ‘stroke’.[11]notwithstanding the fact that the poet herself tells us, if we didn’t know or didn’t remember, that the ‘muffled drum’ is a quotation from Auden’s Funeral Blues.[12] The fall at the end is, after all the fall accompanying a stroke. It makes us see the raised hands in the photograph to which this is the ekphrasis as quite ‘empty’ in the saddest of ways, as if the light shed through the windows were searching these bodies for weakness which they refuse to show, and did refuse to show:

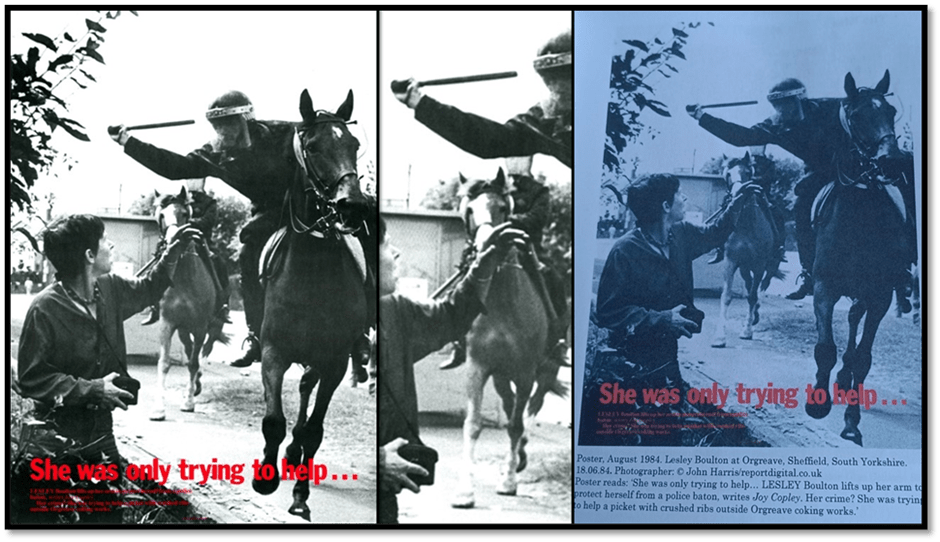

NUM and Strike Support Group posters could emphasis police violence as a threat to everyone in our democracy, as in the poster shown in the book of the attack on a female journalist Leslie Boulton who tried to help a miner who had been struck by a mounted police baton at Orgreave, as below. However, shocking as this picture is in showing a middle-class woman as victim of male police violence, this is not what Wimbush interprets the picture as though she acknowledges the appalling violence implied.

The image she tells us, on this poster is ‘The face that haunts / a thousand pits’. But that disguises that is the face in the preceding line of ‘The woman who lives’. The detail she wants us to see is in the dynamic of seen and unseen relationships that occur in the spaces between people – shown in the still picture or not, for they are a later event in the whole drama. There is horror hanging in:

The space between What was and what Might have been In white and black.

But in the real-time events (not in the binary of black and white, so to speak, other actions occur in other spaces:

The hand that grabs her by the belt pulls her back

Some Orpheus (male and female they) has rescued this Eurydice, whilst the Orpheus that is Wimbush pulls back woman so she is not used as a stereotypical victim but as a witness to what a politicised police may be capable of doing. Indeed the poetry about women is about disrupting too the binaries of male and female. Women stand by the side of men not behind them and ‘pull their daughters forward’.[13]

Men in the Miner’s Strike are realised in new light, even by themselves – sometimes in a awakened consciousness of the toxicity of some prior stereotypes of masculinity, at other times, perhaps not in the case of the ‘Bastard NACODS Scabs’, who ‘roars like a lion / but acts like a mouse’.[14] This is by the way the only picture’s ekphrastic riddle you might not get which is buried in the interpretation ‘built like a brick shithouse’ (bald a brick / and part of the house’), well known in Yorkshire.

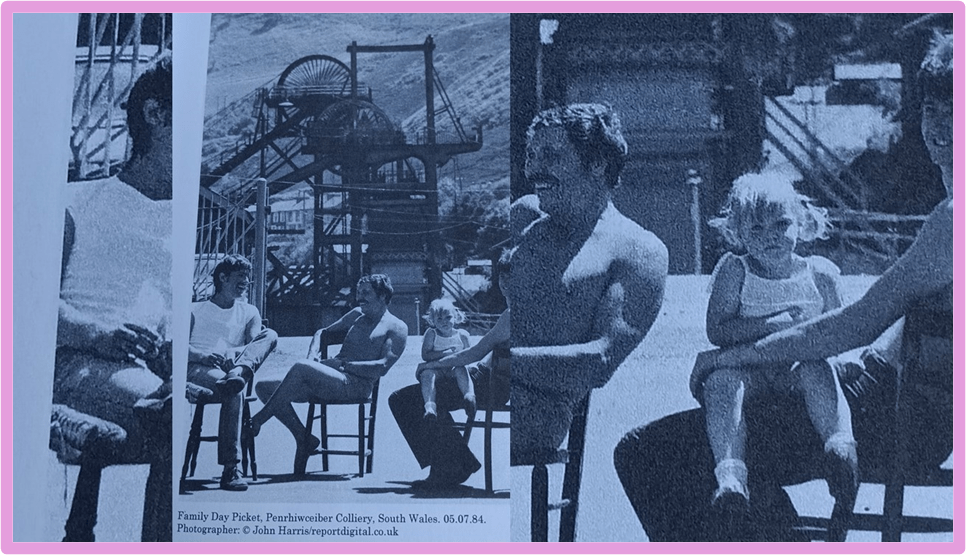

The ekphrasis for the photograph Family Day Picket, Penrhiwceiber named Picketing at Penrhiwceiber contrasts the scrubbed up pit lads who sit not like stereotypical men but men on holiday lacking ‘slack’ in their hairline, where ‘slack’ is another name for coal debris. They are spruce, and scented as conventionally ‘real men’ think they should NOT be, and their slim beauty supports each other and ‘my daughter’s chubby legs’, taking on roles that men in public did not in the mining valleys. The toxic male body they have left behind is the mine ‘splayed / beside cogs and cables / iron and steel – ‘ dour and rooted and still’. Conventional masculine identity was also apparently ‘rooted’, static (still) and silent (still) as the pit is now. But these men have mobile flexing legs no longer splayed apart but resting in their beauty.

And women are not victims but like pit props – they support. In Women Against Pit Closures, they leave men, as they are in the photograph, blurred: ‘In the shadows – / her husband / her father her sons, a ‘New Aphrodite’, who will ‘clamber up, up, up’ not stay at home.[15] And working women in this volume have working independent voices, able to appreciate the history of the working male but also pushing it into a new order My favourite female figure is the woman who passes in modernity for ‘Mother Mary’: ‘Our Lady of the Pit Canteen. Look at her. She reflects back to men their strengths and their camaraderie even when they are naked with each other in’ the pit-head baths’, whilst remembering too they could get a rise out of being in drag (‘dressed up as a bunny girl / at Butlins for a laugh’) but have suffered for their hard work, but they could still be our lady’s ‘garters (an this in Yorkshire accent and idiom): ‘but I’ll ‘ave tha guts fa garters / if them dishes aren’t brought back’. Our lady exists in my background and was formative.

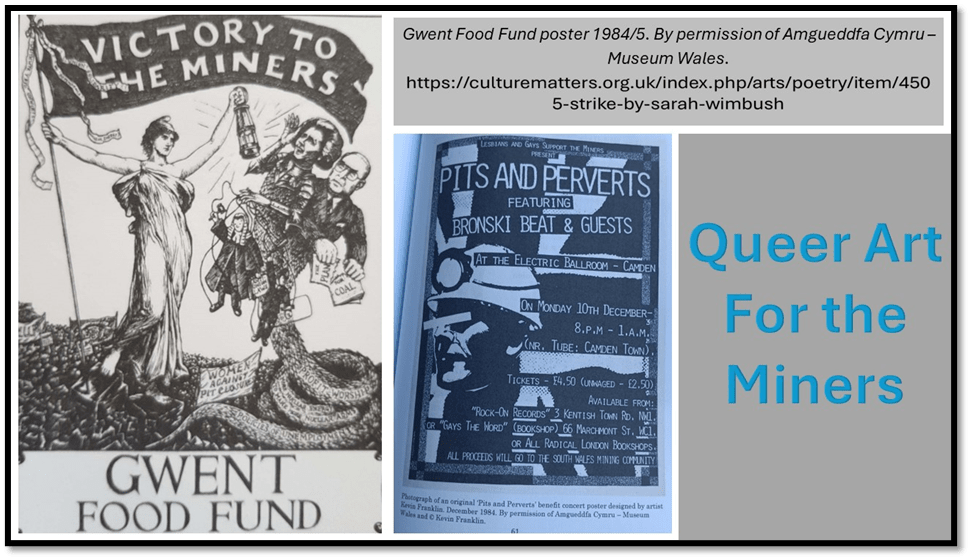

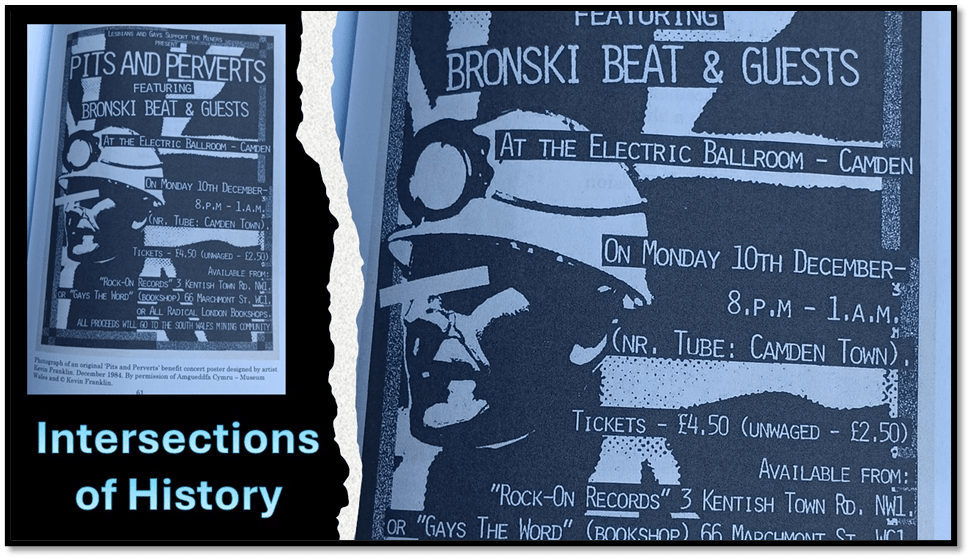

And though the socialist reviews I’ve cited see the poems about the Queer Community Support for Miners, a thing I was part of in London, involving Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) and the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE was usually hard to rouse) from West London. The historical moment of the 1980s was wasted but there was some kind of unification across intersections of left and radical movements (the Labour Party remaining shy of that appellation) and populations of the marginalised, that looked again at how negative images of groups that challenge the hegemonic powers that be at the time, that may now be lost. Whilst traditional left poster art with its portrayals of the capitalist Hydra of puppeteer politicians and placed American entrepreneurs employed to close the coal industry as a mas, there were also new alliance. We were happy to call ourselves ‘Perverts’ in this because the aim was to show that media labels were not representations of the truth but nevertheless would not repress the fun of gay sexuality not out in the sunlight of a shocked public sphere.

The Pits and Perverts poster allowed the ekphrasis of it by Wimbush to animate nearly every queer group attending the Camden Town benefit concert (all spelled out in an end-note by the poet) but also to insist that some miners found that diversity existed in the pits themselves, and that categorical norms would ‘Relax’ as in the Frankie Goes to Hollywood song these categories ‘Spin me right round’, so that miners recognised not only ‘Gay’s The Word bookshop’ but also the ‘queens and kings’ in their own ‘underground’ just as they recognised how social undergrounds where created that divide us. A slogan goes both ways as in this beautiful line: ‘no surrender, forever proud’. These moments I would call Intersections of History for a wide political movement suddenly had it perfectly illustrated that there is no rue Unity or Union with respect for and embrace of diversity.

And I think harder still in the poems is the recognition that scabs are human too – some of them for they too are diverse, and that Silver Birch, Chris Butcher, ‘Maggie’s Judas’ and a ‘Faustian whitedamp Dorian Gray’ who sold his soul to the Daily Mail as the voice of anti – strike ideology is a media creation in reality, though I have some questions yet about the use of the anti-queer language to describe him (‘rimmer of the night’). But other poems show the divide create between working and non-working miner as based on manipulations by power from different quarters, exploited in different ways by Scargill, Kinnock and Thatcher.

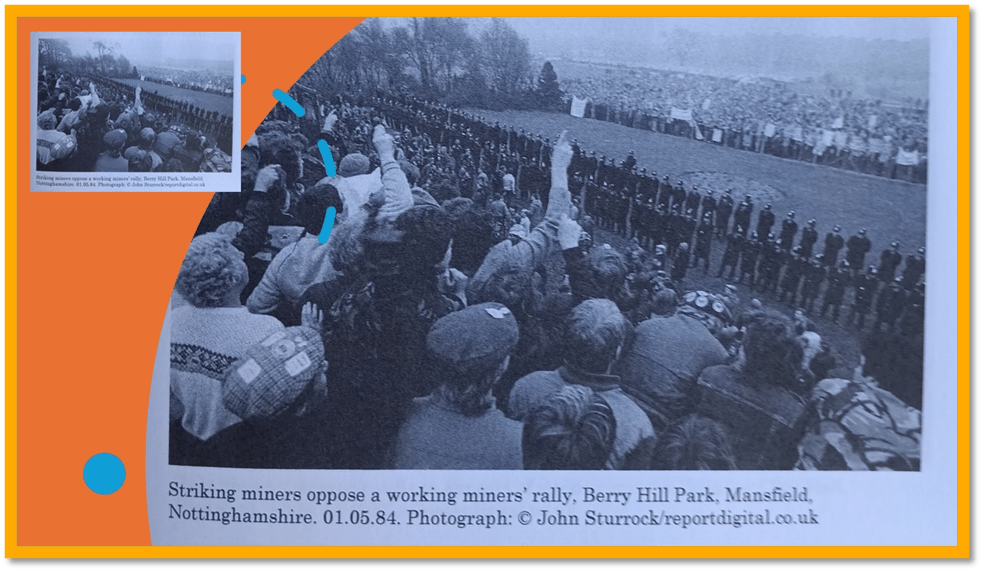

At Berry Hill in the photograph the opposition of striking and working miners is defined by lines of police creating a gap, which Wimbush interprets as productive of the awful crime against strike-breaker Michael Fletcher, who she honours regardless. This is the only truly political poem that shows how ideology can divide us when it is imposed from the top. Here is the photograph:

Can’t you feel the layers Of neo-liberal chaff forming a scab Now an island? And lads, look, see, The black picket fence is smiling.[16]

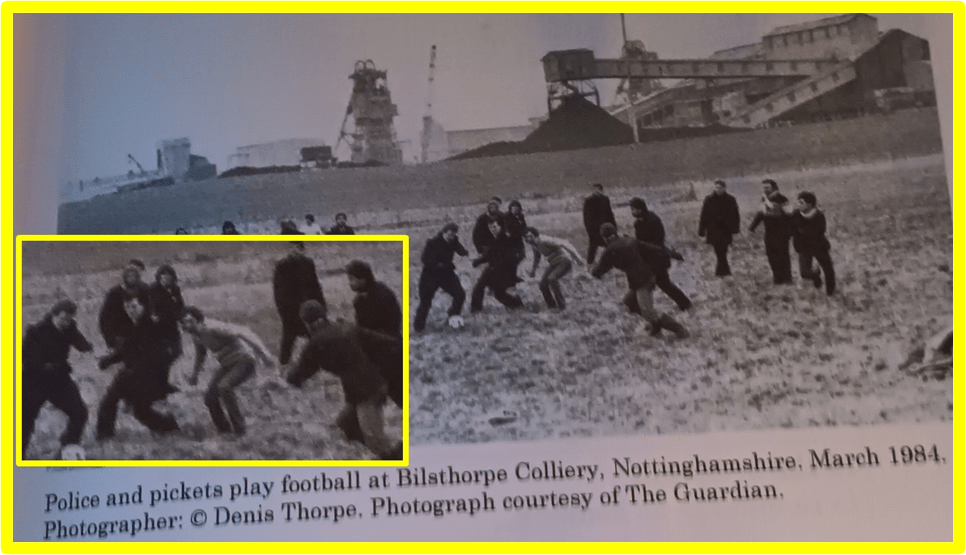

This is a rich poem, suddenly the police in black illustrate the method of a ‘picket’ line (bet here a defensive fence) and we see that scabs are not evil men but formed like those on the skin of the body, and infecting the whole island of the UK (of course many islands but the idiom is forgiving) . The point was to see that even the police smile not in evil but because they had become puppets to neo-liberal threat from above which is never an ideology of freedom for all. At the beginning of the strike, the government had not introduced its flying pickets of specially trained armed police and the police and strikers, all known locally to each other, could play football when off-duty (as in the poem and picture Kick-off). The evil is in process erupting in the viscera ruled by Thatcher – ‘the belly of England’ where it was always intended to create ‘a strike to end all strikes’ but meanwhile the lads remain boys on both sides playing Subbuteo when they co not imagine themselves as ‘Keegan’, which most could.

But in the end, The Miners’ Strike mobilised the toxic masculine ideologies frequently too. This is the case in the poem I use in my blog title:

Action Man takes the measure of the enemy, or perhaps he’s back home pegging out nappies wondering, what has he been reduced to.[17]

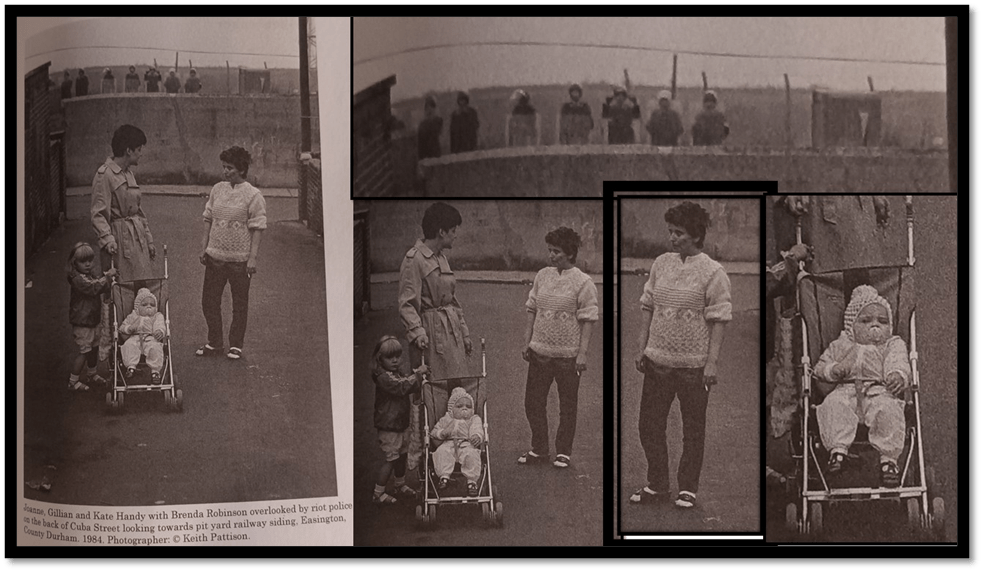

What is the tone of the identification of the men of Easington Colliery in The Police, The Miners’ Wives, Their Children. Who is it who identifies domestic work by men-on-strike as being ‘reduced to’ women? Is it the police, the wives, the children or the men themselves. In my reading the voice is the defensive and fearful one of the police, showing themselves afraid now of these strong women and hiding behind ‘Adrian’s wall’ (get it ‘Hadrian’s Wall’ not far from Easington Colliery where this photograph is taken) preferring to make fun of the striking miners than face these tough supportive women and children. But the most wondrous moment in this poem is where we catch the miner out, just before the enjambement changes the sense entirely of the sentence of the male miner wondering ‘what has he been’. Beautiful. Sonorous reflections crowd into a bathroom mirror.

For:

Easington Blanks Southern occupation –

And these police were imported from Southern forces, unable to penetrate Adrian’s wall, when being ‘blanked’ by the women, anymore than the Romans could face the Scots at Hadrian’s Wall, at least in myth.

And all mining communities are like that, for they had, and in parts still have, a common language that came from mining technicalities but also because of their mining migrant criss-crossing communities. And learning that language is itself a joy of these poems – even the list of closed mines in the opening There is too much to say about the prose poem Our Language, so I will say nothing and hope you buy and read this book. Hershaw anyway is good on this:

An inventory of words forged unbreakably, the opening prose poem of Wimbush’s fine collection gives a précis of what follows: ‘Our Language’ takes sides unequivocally, invoking every mechanism of mining culture, its accouterments and vernacular, its stoicism and its anger, its women. The determiner ‘Our’ declares, as effectively as Tony Harrison in his ‘Family’ sonnets, a sense of belonging, to the class and people of the poet’s origins. On an unremitting journey of demotic terms, bearing defiance alongside ‘snap-tins’, and inferring pathos in all-consuming coal-dust, the language of a lost industry endures.

Even the word / name ‘Arthur’ takes on ‘new meaning’ like ‘GIANT or STONE’. But Hershaw also says:

What the book proves is that “Our language still exists” if nothing else.

I’ll end with some verses from Death by Strike:

Strike is a black lily

falling through the air

like a broken house brick.

Strike is the pressure

of a coal wagon

on a picket line at Ferrybridge.

Strike is a caber

tossed onto a Ford Cortina

inside a concrete block.

Each of those deaths was a miner, the last commemorating a man from the mining community driving a working miner to work when ‘two striking miners pushed a concrete block from a bridge onto his taxi killing’ David Wilkie (35).

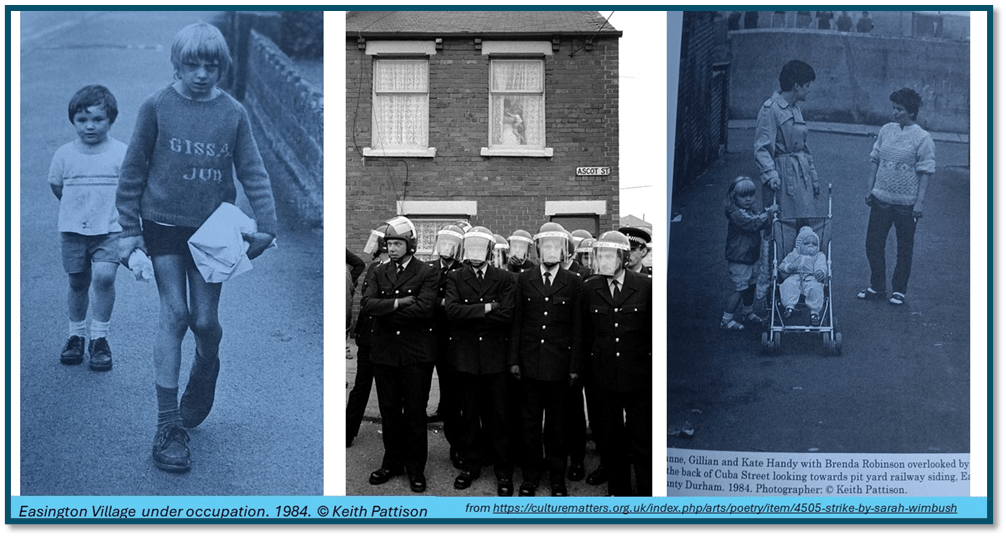

But you can’t leave a mention of mining children without a glance at one particular child from Armthorpe (Markham Main Colliery). The front of his jumper uses the immortal line from Boys From The Black Stuff (that time meaning bitumen – a coal product): ‘GISS A JOB’ (Wimbush wonders what colour these words are for GIVE US A JOB), but the back seen only by the urchin behind says ‘FOR MY DAD’. Hershaw’s extra picture in the middle of this collage reminds us that colliery villages were literally under internal occupation. But look at that boy. As Wimbush’s attempt at ekphrasis says: ‘Is it acceptable to say emaciated in front of a boy?’

Do read these beautiful poems. For poems they truly are. If they are a memorial for you too – all the better. They are to me.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] From The Police, The Miners’ Wives, Their Children in Sarah Wimbush (2024: 54) Strike York, Stairwell Books, 54-55.

[2] Steve Whitaker (2024) ‘Blown Apart By The Sun: Strike By Sarah Wimbush’ in The Yorkshire Times (1:02 AM 12th April 2024) available at: https://yorkshiretimes.co.uk/article/Blown-Apart-By-The-Sun-Strike-By-Sarah-Wimbush

[3] Rupert Loydell (2024) ‘Review: Strike by Sarah Wimbush (Stairwell Books)’ in Tears in the Fence: an independent international literary magazine (9th March 2024) Available at: https://tearsinthefence.com/2024/03/09/strike-by-sarah-wimbush-stairwell-books/

[4] William Hershaw (2024) ‘Review: STRIKE by Sarah Wimbush’ in Culture Matters [online] (Saturday, 16 March 2024 10:52) available at: https://culturematters.org.uk/index.php/arts/poetry/item/4505-strike-by-sarah-wimbush

[5] BBC July 1991. See Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign. Cited Wimbush, op.cit: 82.

[6] Scargill in ibid: 4

[7] ‘The word comes from the Greek ἐκ ek and φράσις phrásis, ‘out’ and ‘speak’ respectively, and the verb ἐκφράζειν ekphrázein, ‘to proclaim or call an inanimate object by name’. From: Wikipedia on EKPHRASIS (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ekphrasis).

[8] Steve Whitaker (2024) ‘Blown Apart By The Sun: Strike By Sarah Wimbush’ in The Yorkshire Times (1:02 AM 12th April 2024) available at: https://yorkshiretimes.co.uk/article/Blown-Apart-By-The-Sun-Strike-By-Sarah-Wimbush

[9] Sarah Wimbush, op.cit: 62f., The poem originally appeared in 2023 in Stand Magazine [Stand 238: 21(2), June-August 2023] (see https://www.standmagazine.org/cgi-bin/scribe?item_id=3202#:~:text=This%20poem%20is%20taken%20from%20Stand%20238,%2021)

[10] ‘The Black Hole’ in Sarah Wimbush op.cit: 64f.

[11] I used to work with mining elders as a social worker in Durham. Co-Pilot (AI assistant for ) answered thus on the issue (12/09/2024): ‘Working in a mine can indeed pose certain health risks, including an increased risk of stroke. Factors such as exposure to dust, chemicals, and physical strain can contribute to this risk. Here are some key points to consider:’

- Exposure to Dust and Chemicals: Prolonged exposure to dust and harmful chemicals can lead to respiratory issues and cardiovascular problems, which are risk factors for stroke.

- Physical Strain: The physically demanding nature of mining work can lead to high blood pressure, another significant risk factor for stroke.

- Stress: High levels of stress, common in demanding jobs like mining, can also increase the risk of stroke.

[12] Ibid: 83

[13] Women’s Support Groups in ibid: 30

[14] Ibid: 46

[15] Ibid: 36

[16] Ibid: 14f.

[17] From The Police, The Miners’ Wives, Their Children in Sarah Wimbush (2024: 54) Strike York, Stairwell Books, 54-55.

2 thoughts on “What is the role of poetry in mourning and celebrating the political past. This is a blog on Sarah Wimbush (2024) ‘Strike’ and The Miners’ Strike of 1984-1985.”