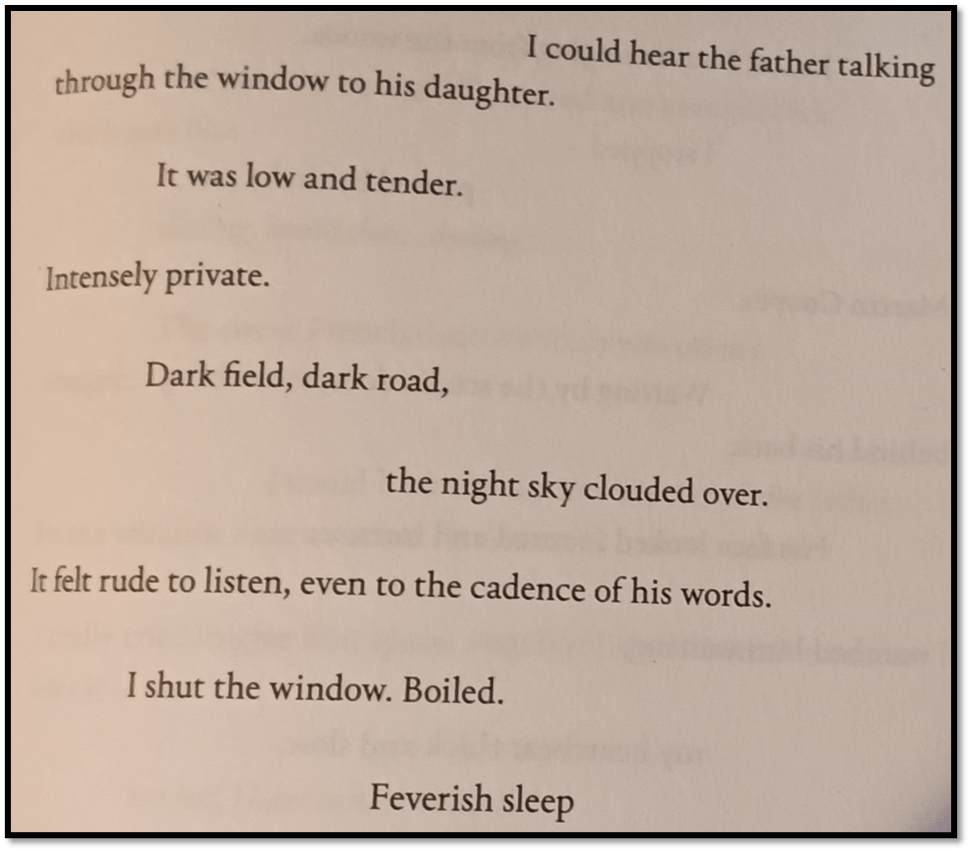

‘I could hear the father talking / through the window to his daughter. / It was low and tender. / Intensely private. / dark field, dark road, / the night sky clouded over. / It felt rude to listen, even to the cadence of his words.’ [1]Speaking to Emily Dinsdale of Dazed (online magazine), Ella Frears says of her new artwork that: “It’s not verse, but I guess when I started writing through this angry voice, I found a cadence that makes it slightly unsettling”.[2] Who do cadences unsettle us? This is a blog on Goodlord (2024) by Ella Frears, Rough Trade Books.

Although the word is ambiguous and its meanings from different domains of usage can further complicate what might be meant by it, cadence in poetry has a specific history becoming more common from 1915 in relation to the schools of thought in poetic form related to vers libre (free verse) and the use of that ‘form’ by Imagist poets, like HD, and sometimes Ezra Pound, for instance. The basis of the sound values of such poetry was thought to be the ‘falling’ rhythms based on patterns of stress irrespective of syllable counts in a line. In Frears’ statement of the poem cadence unsettles because it finds a kind of sad music in the use of words whatever their apparent determining motivation. Snatches of verse nevertheless are scattered throughout the work, if not as largely as references to Thomas Hardy’s story Exploits at West Poley.

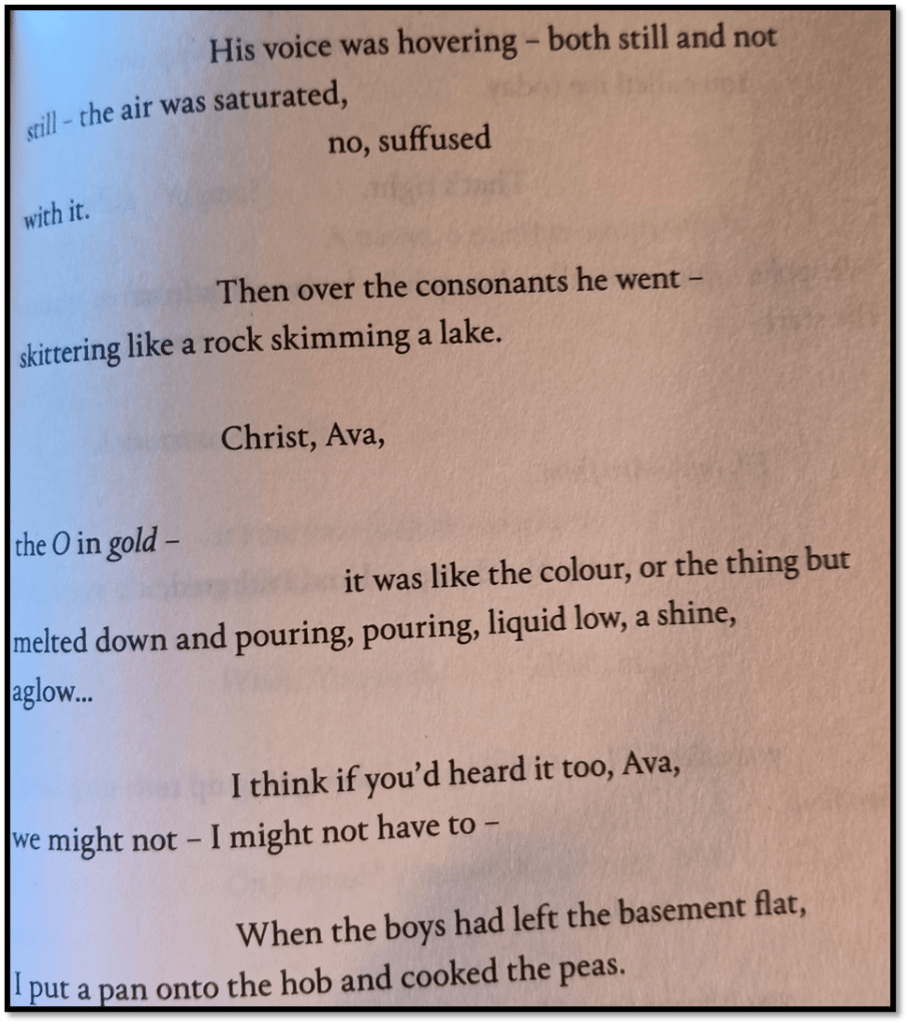

There are sly references to verse lines from Hamlet (the ghost scene), Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Coleridge, one named one from Robert Frost and one other unacknowledged from Ted Hughes’ most famous poem (The Pike) plucked in the story at random from ‘the exam anthology in my bag’ when the narrator was at school.[3] The last reference relates to the narrator recalling an episode from her school life when from a visiting orchestral group, each learner was allocated an instrument for whom they must write a piece of music that would then be performed to the whole class by that instrument. The instrument she is allocated is a baritone voice which produces her setting for a Hughes phrase ‘green tigering into gold’ . Frears’ description of it in the voice of her narrator is full of cadences. In the instance I am about to cite (by photographing the page of the book to give an idea of the irregular delineation style of the words) seems much like what the Duke of Orsini describes as a cadenza in music in the opening of Twelfth Night:

That strain again! it had a dying fall: O, it came o'er my ear like the sweet south, That breathes upon a bank of violets, Stealing and giving odour! Enough; no more: 'Tis not so sweet now as it was before.[4]

In Goodlord, the following describes the effect in the baritone’s voice of a duration of the music following a moment where ‘His voice was hovering – both still and not / still – the air was saturated, / no, suffused / with it’.[5]

From: Goodlord p. 189

The last two quoted lines are there to illustrate the transition in the rhythms, from those of song to those of everyday prose, where flow turns into plod, an aria gives way to recitative in a seventeenth or eighteenth century operatic work. There is something both materially substantial and, simultaneously, not so in this description of falling or skimming liquidated solids or stones in mid bouncing arcs of flight. They might be both densely heavy or light in weight and shine qualitatively like light. It is quite evidently, as imagery and sound, beautiful; touched by light alliteration, repeated words and internal rhyme. The narrator seems to see it as a moment wherein the differences between herself and the letting agent of her flat, represented by Ava her allocated worker, might be resolved. But that moment of resolution is also one where the certainty of things becomes compromised, the solidity of quantitative materials to fade into their qualities to the senses and the apparently ‘settled’ nature of the world we know radically unsettled, moving when it needs to rest and yet finding no safe space to rest in.

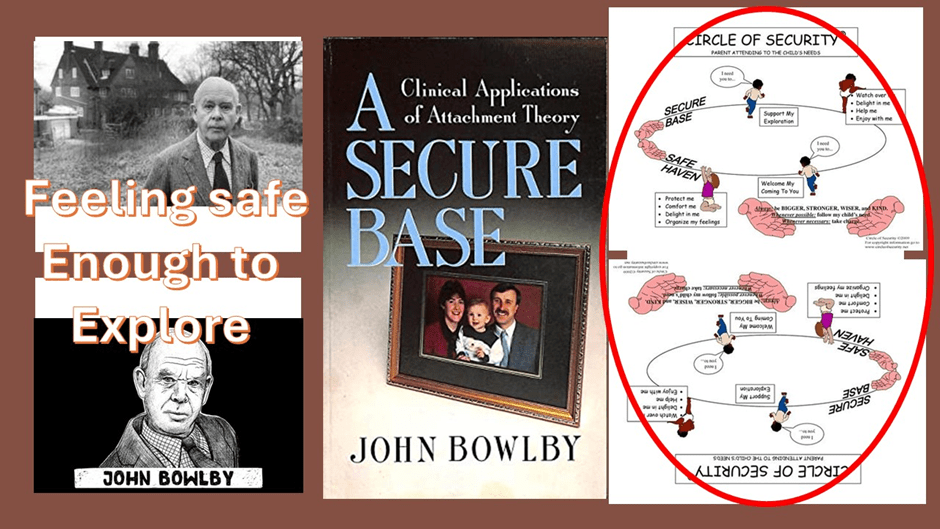

For me, the key feelings and images in this novel-cum-poem-cum- …, well lots of things, are about the search and inability to find a ‘safe space’. According to John Bowlby, a ‘safe space’ (in his terminology ‘a secure base’) is an internal cognition, built from sense, emotional and cognitive data by the very young infant into an image of security that has different forms, but most usually that of being ‘home’ or at home’. It promotes exploration in the spaces that are other than itself but remains a thing we can return to, at least internally if not in reality. In fact in adults, this space isn’t (or doesn’t remain) any one place, though it takes that form conventionally in settled times socio-economically , socio-culturally and psychosocially but is transferable because projected outwards from its original form that was introjected in childhood. Things get edoted in tjese processes of transition. Home may be entirely an imagined mental-sensuously-emotive space that is accessed only mentally. When things become unsettled in adult life – in disruptions of unfamiliar travel or more enduringly in forced migration or homelessness, or in mental/bio-neural trauma like depression, generalised anxiety, dementia or other form, ‘home’ is any space that makes you feel safe because the thing that once was ‘home’ is now unattainable in reality or even memory.

In Ella Frear’s account of the real circumstances of herself as she was occupying unstable rented spaces as the ‘equivalents of a ‘home’ is the origin of the feeling that one’s sense of a secure base and safe space’ or ‘home’ is at risk or even already in the process of breakdown is the motivating force of the poem. However. this does not apply only to the renting of property in which to live. Emily Dinsdale addressed this in her interview with Frears thus, saying that the narrator’s sense that her boundaries are being encroached upon, by environmental noise, men visibly peeing in the space below her window, or the demand to register with an letting agent’s online means of improving its functions that Goodlord proposes to be. Dinsdale says (her words in bold):

It really evokes the feeling of people encroaching on her in various ways, and the sense of her boundaries being very permeable – not just her personal and physical boundaries but also her living spaces. There’s a transience in her life as a tenant, she doesn’t have a safe home anywhere. Was that a conscious correlation on your part, or is it all bound up with the same feeling for you?

Ella Frears… As soon as I started following that anger about housing, it didn’t take long for me to follow that uneasy feeling into other places where that feeling occurs as well. And mostly that has to do with boundaries, with the body and interactions that feel atmospherically similar to what the housing crisis was doing to her.

… When you live in that rental aesthetic, it does something to you. In trying to figure that out, other elements came in and, for me, they meet atmospherically in ideas about the body, housing, aesthetics and patronage. All of those things feel connected.

…. If you’re on your own in the countryside, it might be a more romantic setting but you’re not necessarily any safer or less lonely and there’s this overriding pressure where the trust sponsoring her residency in the book acts almost like a landlord.[6]

It really appears from this account, covering diverse episodes in the work that the safety of spaces we inhabit is often illusory – even illusory, we will find, in the internal space the narrator constructs to live in in her sleep, the Big House (of which more later). The trust at the home it sponsors for resident artists at Boatswain’s Clench (which really does sound an unsafe space) watches and checks up on her through the eyes of a gun-carrying landowner – so much so that she even has to construct a model ‘double’ to enact her staidness in her quarters. But doing this makes her no safer from intrusion, in fact less so.

As the excellent discussion in Dazed above shows, not only houses have intrudable boundaries but so does one’s body, mind and sense of aesthetic creativity. The idea of being ‘unsettled’ in this work is the impossibility of ever ‘settling’ into one secure ‘safe space’ or’ secure base’.

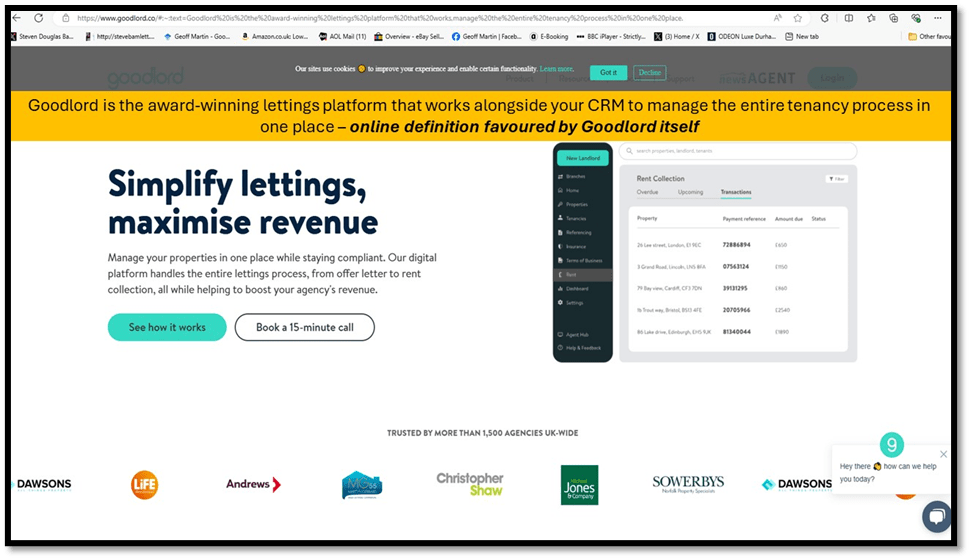

Goodlord in the title is the means in particular in which patriarchal capitalism intrudes on the life of persons. In fact, Goodlord refers to a real online tool used by property letting agencies and Frears’ description of it is accurate, including its means of generating income from the service it offers to letting agencies by commoditising the huge database of persons, who are literally forced by their letting agencies to sign up for it – as the character Ava tries to persuade the narrator to sign up. Such ‘big data’ is a rich resource on the internet, as ‘big data’ consumer information helping capital to be invested in order to achieve enduring large profits based on that data. For big data guides capitalists to make money from commodities that consumers can most easily be persuaded to desire: ‘it’s capitalism on capitalism, Ava! I implored’.[7]

And it is patriarchal because even the language of rental administration is male or acts in male fashion: landlords, Goodlord, God or Gods are all male, even if only in symbolic name. And men like to be known, even assumed to be good. Yet it unsettles that Ava, clearly a woman, is the agent of something male, as it does the narrator when she discovers that of herself or other women too in the book. As it opens, we don’t know if it is the ‘Good’, the ‘lord’ or the combination of both that unsettles Frears and gives her writing such cadence:

Dear Ava, It’s not your fault this caught me like it did – Goodlord – the name disturbs me most. As though we’re meant to pledge ourselves, to call our faceless landlord good …or God, and I should – should I? – feel graced, or blessed to live under this roof?[8]

Never once is masculinity qualitatively identified here, but it is assumed. Indeed this opening of the book cuts deeper when we hear of the narrator living alone in a borrowed house of a landlady standing in for her dead husband and pretending to be its caretaker and of its paying guests that she hears a father reassure his daughter presumably of her safety – but possibly not because the conversation being ‘intensely private’ is therefore suspect. I cited this in my title but here reproduce the text as published in its ‘unsettled’ delineation. Even if the father whispers reassuringly, we know that his wife, her mother, has been murdered without clarity as to cause or agency. It not only ‘unsettles’, it is chilling: [9] This is the more so when the woman in the work itself, is obsessed with a buried child – one within her, dug in deep by mechanical ‘diggers’ that dig their own graves, as we shall see.

What do I mean by ‘unsettled delineation’? I think this matters because feeling ‘unsettled’ is central to the work’s themes of being ‘houseless’, ‘homeless’ , insecure or unsafe or haunted by ghosts or ‘madness’, like being temporarily in the bed of a boy who will soon after commit suicide (in one of the most unsettling episodic memory scenes in the book).[10] It is a feeling called in the word ‘housesick’, an important derivation that unsettles the word from ‘homesick’.[11] We read, as we see, by virtue of the use of an eye mechanism that operates by continual saccades, which become in the event entrained to shapes and designs that are expected or predicted top-down in our mental apparatus from its introjected and recalled stores of models of the ‘readable’. So durable are these mental stores over time that we associate them with the natural, the right and the settled. In reading, for instance, the eye is trained, settled, to read lines of prose and verse from left to right and top to bottom.

This is at least how it feels – but it is a feeling easily disrupted by attempting to read a non-Western language, where script is organised from bottom to top, and right to left, as in Arabic or Hebrew. Such writing unsettles the unaccustomed Westerner. But so does text that refuses an order placement in delineation, that tries to make sense of space in order to locate beginning and end points for reading of lines, looking for a common pattern between them or a meaning for being as they are. That effect I describe here is less felt in the opening lines of Goodlord, which look very like a settled verse form (though with enough internal disorder as in all good poetry) unlike the delineation in the scene cited by photograph above which veers between enacting what it means from the more conventional comforting ‘line’ with ‘cadence’ in it [and which is about ‘cadence’] to other lines disjointed in different ways – like the last two lines.

The ‘verse’ itself cooperates with the creation of a feeling of the uncanny (the unfamiliar within that thought familiar – such as the words of a Dad comforting his daughter and making her feel safe. But men in this novel rarely help to create safe space, except as an illusion to entrap, like the iconic Snake Boy who owns a ‘bar’ (of bars and boundaries more later), the Boatswain with his ‘clench’ , even weedy boys who turn bad and, of course, the awful Norman Cooper, a master of the creation of male threat. Much of the work forces on us scenes of men in groups, from different social classes, being shown for what they can be at their socialised worst – especially in bars, clubs or country pubs, but even old men alone on a train can be as gross, sexualising every aspect of their encounter with a young woman.

Men force themselves on the narrator, although sometimes she cooperates because it is ‘seems’ rightly or wrongly a safe thrill. The narrator calls this her ‘inner barmaid’, the woman who goes along with the thrill of sexualised behaviour in the knowledge that she has a bar between her and the male punters. But bars, like all boundaries, can be intruded upon, or over, at first by safe banter but then by physical action, jokey at first – like the old man on the train who ‘jabbed me in the ribs’: ‘My body shifted cold. My inner barmaid shrank’.[12] This is born of behaviour that Ella Frears discusses in her interview with Dinsdale when asked about consenting behaviour in sexual situations:

Would you say there is an ambiguous place between passivity and consent?

Ella Frears … I am interested in what happens when somebody has desires that are potentially closer to the edge. … incredibly curious about what will happen next with somebody, whoever that is. And so she allows things to go further than you might imagine somebody would, even if she’s not into it. There’s a feverishness to the book. I wanted it to feel like it was constantly vibrating close to the edge.[13]

This ‘living in the edge’ feeling that women know (I have written about it in regard to Amy Liptrot in the blog at this link) as defining their sex/gender experience, in interaction with men, even leads to sex/gender exchanges – such as in the moment where the narrator becomes the depressed boy in whose unwashed bed she sleeps or, later in the work, becomes a successful bar-room physical fighter shaming men at their own game (even the bouncers), or wearing a ‘captain’s hat’ (a constant refrain), or finally and more complexly feeling mirrored by a male neighbour in an identical room made insecure and unsettled in space paradoxically by his mother: ‘ ..- he mirrors us, spatially at least – ‘ and in this way / I feel connected to him. …. He’s sick a lot’.[14]

Men then, as the last example shows, aren’t presented without nuance but as entrained entitled seducers when acting to some norm of socialisation that stresses their ownership of women as some kind of property, like Norman Cooper, who texts her at Boatswain’s Clench, with the words: ‘playing hard 2 get?’ [15] But it this idea of the ‘ownership’ of women as property in a man’s property that is predominant. Propert is where kept women are kept. This can be so even when the ownership is at a distance and vicariously managed by a woman – like Ava and the B & B landlady – that determines the attitude to Goodlord as a name in the business of property administration as a ‘linguistic insult … pointlessness’, to which Ava on the telephone (whilst ‘making faces for your colleagues – I could feel it’) says sarcastically ‘We’re getting deep now’.[16] For some women buy into, may have to buy into to survive economically and psychologically, that male control.

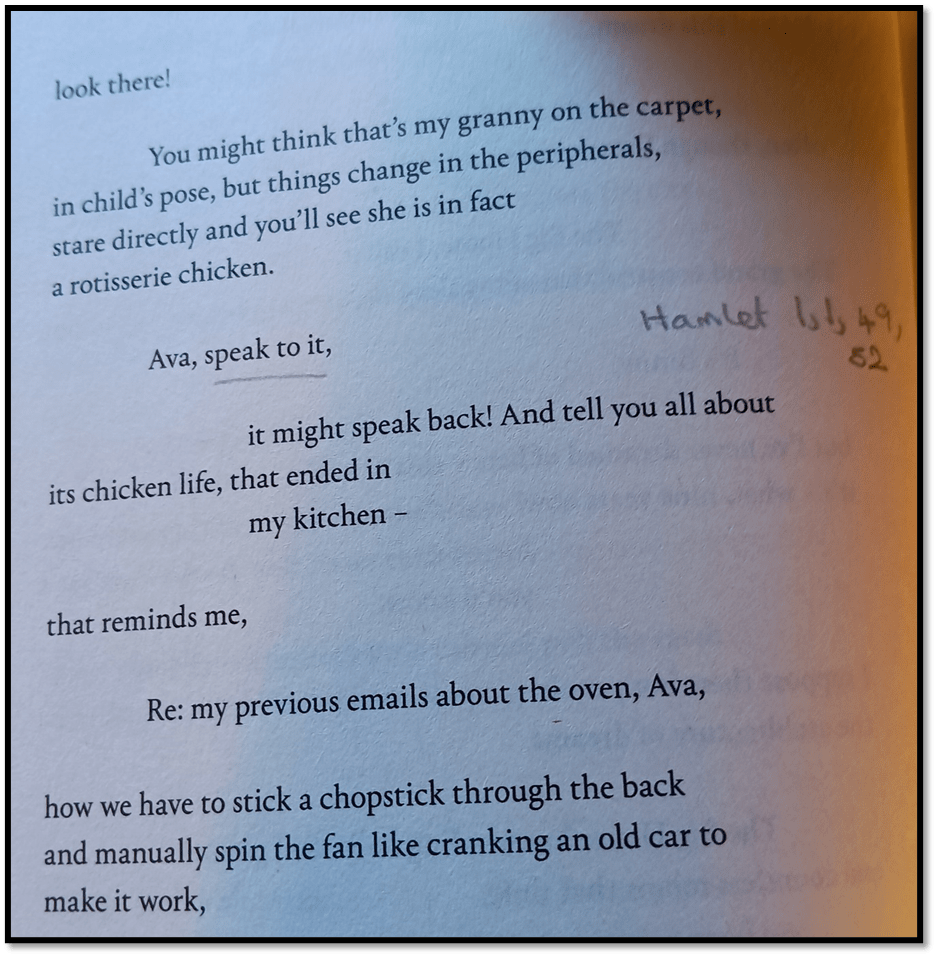

I have moved necessarily a long way from internal safe spaces, but that is because we need context to understand them in this work. They seem represented at first, but less so later for reasons I will explore, by the extended metaphor (ostensibly a product of the narrator’s dreaming and waking fantasy process) of The Big House’. That house is so unlike the cramped stale flats rented out vicariously by Ava. It is described early in the work over a page of text, with its ‘winding halls, and grounds, / and countless rooms that shift’ sounding a bit like both a snake (‘winding’) and a shape-shifting ghost which also haunt the work as the ‘architecture of dreams’: ‘The grand construction of my sleep’.[17] It is a thing where an old ‘granny’ can live on the carpet ‘in child’s pose’ and indeed is a thing likened subliminally to the ghost of Hamlet’s father, for this dream-space is we shall soon learn, far from a safe space but another patriarchal trap, like the relationship of Hamlet and namesake Dad. Here is Hamlet Act 1 Scene 1 line 47ff.(my italics):

MARCELLUS

Peace, break thee off! Look where it comes again.

BARNARDO

In the same figure like the King that’s dead.

MARCELLUS, ⌜to Horatio⌝

Thou art a scholar. Speak to it, Horatio.

BARNARDO

Looks he not like the King? Mark it, Horatio.

HORATIO

Most like. It ⟨harrows⟩ me with fear and wonder.

BARNARDO

It would be spoke to.

MARCELLUS Speak to it, Horatio.[18]

In Goodlord, this is mirrored, where the woman of the dreamt house is reduced to a thing in a man’s kitchen, that the narrator only thinks is hers – a ‘rotisserie chicken’, a natural thought where every faulty thing in your kitchen, even the oven, is owned by a male’s agent who won’t mend it:[19]

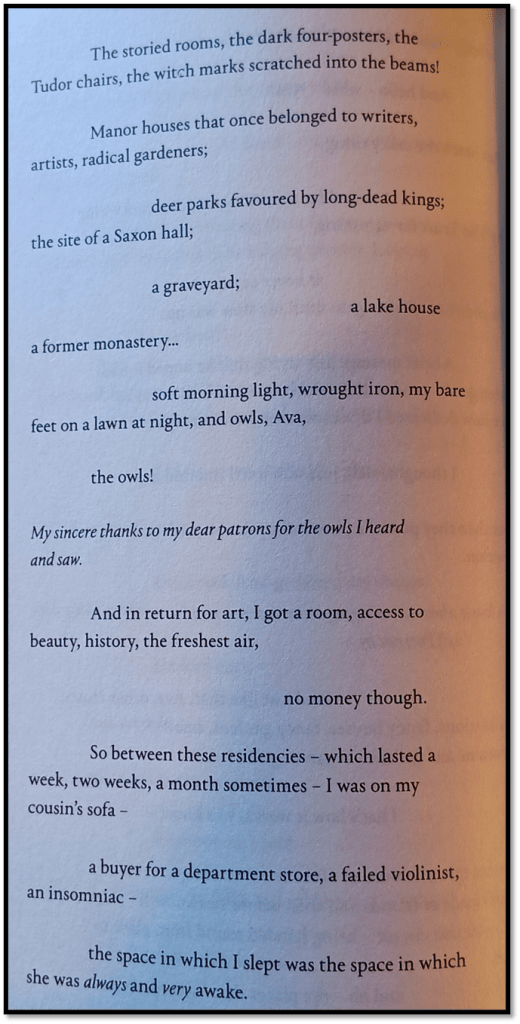

And this unsettling stuff is nevertheless uproariously funny too – on the edge in every way. In fact close reading is even less needed for the story itself will soon show that the Big House is a fantasy built from memories of a house, a father’s house, but also a house in which artists are patronised (in all three of the linked definitions of the word) by male art institutions who act as art patrons. The narrator remembers when she was offered art residencies that have helped her temporarily solve part of her accommodation crisis – for a unsettling short duration – ‘handed round from place to / place’. It is often the more worrying that these ‘big houses’ often ‘belonged to writers, artists, gardeners’ in a rather different past of pre-commercial art:[20]

Every Gothic instance in this unsettles, even the witches marks when it is possible that you living there might be one of the evils this apotropaic mark is meant to ward off by male institutions of ‘long-dead kings’ or a ‘monastery’ and which has, and has the feel of, ‘a graveyard’. Owls are ambivalent, for though they may be witches’ familiars, they are also the symbol of Female knowledge, of Pallas Athene. Women in patriarchy remain like children, unless they ape male socialisation as raptors, and rapers: nevertheless they end up kicking what looks from the outside like ‘a giant pile of leaves’ (a sign of declining seasonal time) but in which she realises ‘there was a child / concealed inside’. Like Bertha in Jane Eyre, women are forced to have someone (a man) who ‘boxed your inner child and / shoved her in the attic?’[21]

Space that is owned and settled by others makes the settler in debt to its owners – payment of rent, or a kind or tolerance of disruption is demanded. Even if some of its gifts of being allowed to settle for a while are beautiful, they don’t add up to a secure living in temporal or monetary terms. You are still ‘unsettled’. Houses that once stood on the ground are dug from underneath the ground by diggers that go so deep they cannot be retrieved and must in part dig their own graves and stay there, buried alive.[22] In the end we all.seem to live in basements. The study of unsettlement is a learning offered by many human experiences, regardless of the gender of the learner. For instance the narrator stays one night with a friend of her mother’s in her absent suicidally depressed son’s bed. The narrator learns fom tbis that she would never want to be a boy but he for a time possesses her, like suicidal ideation itself. Like his bed and his room this posession is ‘pitlike, cavelike. / Desperate and damp’.[23]

Goodlord is a work in which, though a story of displaced adults ‘greedy for those spaces’ where the self might expand to the larger limits of a Big House, is still ‘restless’, and ‘bored’ like thecteenage experience in the last story Ibtold from it. All possession of people, things and spaces is at a distance, owned by a lord’, it is a ‘lot’ you have to accept but that is merely mortgaged or loaned to you, as she says directly but pleadingly to Ava:

I couldn’t stop glitching over the one same truth – Goodlord. Goodlot. Goodloan.[24]

And the mark of the existential fear, a word that get some mileage in conversation in the book, is the fear of passing time, that sometimes feels like a train you MUST board in a dream, encouraged by a male doctor. As a child, the narrator had hallucinations of ‘clocks, where no clocks were, the hands spinning / at a weird speed, too fast but also sort of … lagging’, in some sense this describes the metrics of the ‘verse of this work too, as does a ‘ceiling collapsing’.[25] These childhood visions, early in the work, return much later, but are implicit throughout, when the narrator reflects that: ‘It’s strange to be a child and fear time’ (though this theme is in Carroll’s Alice books) – and it’s also a reflection on poetic metrics.

Vivid in the dark, they’d rush and lag and stretch the night as though to say, no amount of counting, portioning, measuring will help you here- all this cannot be quantified will not be stopped.[26]

At the end of the work are attempts, of which art is one (as in the Yeats poem often cited to Ava) to ‘still time’ or find ‘still time’ that is both motionless and silent, the stuff of art according to Keats speaking of a ‘Grecian Urn’.[27] In Goodlord these attempts only meet with more feverish haste – ‘sickness unto death’. I link the latter to Kierkegaard not to claim a Christian existentialist resolution, for such is NOT available in this work unlike in Kierkegaard.

What the work is left with are moments of feverish madness, the playing about on the edge of adventure and the fear of being overwhelmed where all bars and barriers no longer hold back forces of any kind, and people confront life as an existential ‘hole’: ‘I felt the pain again – another hole’, although that refers to a hole in her tights from a man’s inability to maintain boundaries with his cigarette, or his penis.[28] Men promise continually to feed her, until they show that that it is their sex that needs consuming. This seems to be the root of the narrator’s obsession with ‘gummy worms’. As she stuffs her own mouth with them, she is confronted, ‘worm in mouth’, with the ‘watchful eyes of a man’ / who seemed to know me’. He turns out to be ‘the first boy / that I ever blew’.[29] In this moment an obsession on the edge is bared.

And the pain for the narrator is the certainty that Frears still echoes in saying to Dinsdale that her work is definitely not verse, though still able to say that it is one of its potentials: “somewhere between an epic poem, a novel and auto fiction, as told by one long email to an estate agent from a sort of rage-filled, slightly unhinged tenant” .[30] Yet there is the desire for the epic poem that takes the unlikely focus of a ‘passive woman’. It is a theme that leads the narrator to make her own female Golem-cum-double out of a shop mannequin (and that gendered name is significant).[31] Frears says to Dinsdale:

I’ve been interested in a passive female protagonist for a really long time. … You can find yourself in dark, unsettling – or beautiful – situations. / As a poet, there’s an element of being an observer, which I guess has done something to my writing voice… there’s an observational quality and it’s less active than you might encounter in other works where the protagonist is making things happen… And that is a really interesting place to find anger within because it’s more complex than just non-consensual. … Because when you allow things to happen, there are always peaks and troughs in terms of desire, …

She attacks this in Goodlord with a deeply layered reference to Orpheus, the trans-poet in the extreme. She refers to the fact that Orpheus was active enough, to his doom, to look back for Eurydice but it may be too that he is able to look back to the past of great epics constructed out of lyric motility. When the narrator says it doesn’t matter who she has ‘grinding’ on behind her – the language covering dancing and passive anal sex from a man, I think the ‘grinding’ references too her voice, a grinding not a mellifluous one, for no poet now can be Orpheus. Check the section out for yourself. It is so subtly on the edge of these meanings.[32]

The upshot of this poem after all is also on the edge. It is a lyric plaint such as those Tudor poets excelled in, a thing Frears plays upon by having the narrator, say her ‘email’/ poem’ is a ‘complaint’ – / a formal one’, playing too on the meaning designating aesthetic form or genre.[33] Had Edmund Spenser being using the word complaint, we would know he meant a pastoral elegy, as in the unambiguously entitled Complaintes of 1591.

The first page of a text on Spenser: Spenser’s “Complaints” and the New Poet on JSTOR (https://www.jstor.org/stable/3817877)

A complaint to Spenser is a formal elegy of the effect of passing time on human aspiration to all manner of things and so is Goodlord, with a wonderful true feminist angle, that also addresses the problem of masculinity married to its temporal moment of entitlement. One such story is that of the beautiful Paul, whose story we hear from the narrator’s friend, ‘regressed’ as she is to the smallest of basement flats. He owns the home the friend was living in but is no great shakes as a conventional man. He gets ‘stitch’ on a run: ‘A little / puddle of a man. She felt disgusted but walked back to check/ on him’. He evicts her from his love, his life and her home at that moment because he hasn’t loved her ‘for some time’. The woman who waits on male time has all the more reason for plaint against time, formally – even to the misnamed Goodlord.

But this work (damn it – to me it’s a poem!) is actually about the way patriarchal capitalism in its present advanced mode grinds all of us so that we get erased in its mechanisms, especially the young, but even if we are wage-slaves to the system like the airhead Ava. Kate Simpson, surprisingly in The Sunday Telegraph, says it quite well:[34]

You will see I could write forever on this luminous and numinous work of ghosts and monsters behind the housing crisis and the crisis of sex/gender relations. The new Labour government is addressing the continuing crisis by freeing up the private housing market.

Do read Frears’ work. It is compelling HOWEVER you read it. Read it as you!

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Ella Frears( 2024: 153) Goodlord, Rough Trade Books

[2] Emily Dinsdale (2024) ‘Goodlord: How an ‘unhinged’ email became a rage-filled novel’ an interview in Dazed [online] ‘available at: https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/62988/1/goodlord-ella-frears-email-novel-estate-agent-rough-trade

[3] See respectively for the (sometimes subliminally) cited verse examples; Frears op.cit: 10, 44, 100, 118, 167, 187.

[4] Shakespeare Twelfth Night Act 1 Scene 1, lines 4 – 8. Available: https://shakespeare-online.com/plays/twn_1_1.html

[5] Frears op.cit: 189.

[6] Emily Dinsdale (2024) ‘Goodlord: How an ‘unhinged’ email became a rage-filled novel’ an interview in Dazed [online] ‘available at: https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/62988/1/goodlord-ella-frears-email-novel-estate-agent-rough-trade

[7] Ibid: 191

[8] Ibid: 7

[9] ibid:153

[10] For that last scene – see ibid: 157 – 159

[11] Ibid: 11

[12] Ibid: 108

[13] Dinsdale, op.cit. My italics

[14] Frears, op.cit: 174. For the best ‘captain’s hat’ moment see ibid: 193

[15] Ibid: 140, see from 138 for introduction to him in ‘a group of rowdy men’.

[16] Ibid: 191f,

[17] Ibid: 9f.

[18] https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/hamlet/read/1/1/

[19] Frears op.cit: 10

[20] Ibid: 161f. (below is photograph of page 162)

[21] Ibid: 169

[22] Ibid: 8

[23] Ibid: 159

[24] Ibid: 166

[25] Ibid: 14

[26] Ibid: 12f. (author’s italics)

[27] Try out ibid: 208, 215

[28] Ibid: 182

[29] Ibid: 112

[30] Cited Dinsdale op.cit.

[31] See ibid: 146ff, 160f.

[32] See ibid: 195f.

[33] Ibid: 164

[34] Kate Simpson (2024) ‘An email to make any estate agent terrified’ in The Sunday Telegraph (9 June 2024).

2 thoughts on “Speaking to Emily Dinsdale of ‘Dazed’, Ella Frears says of her new artwork that: “It’s not verse, but I guess when I started writing through this angry voice, I found a cadence that makes it slightly unsettling”. Why do cadences unsettle us? This is a blog on ‘Goodlord’ (2024) by Ella Frears.”