‘Real, unreal; inner, outer – always debatable land to her. … He sees his dead daughter. What’s that if not a disputed boundary?’ [1]Greek myth contained numerous contesting stories about its protagonists. The point always was to choose a story that revealed people who experience the world, and describe and act in it in ways that effectively negotiate inner and outer worlds in which we can believe. This is a blog about Pat Barker (2024) The Voyage Home Hamish Hamilton.

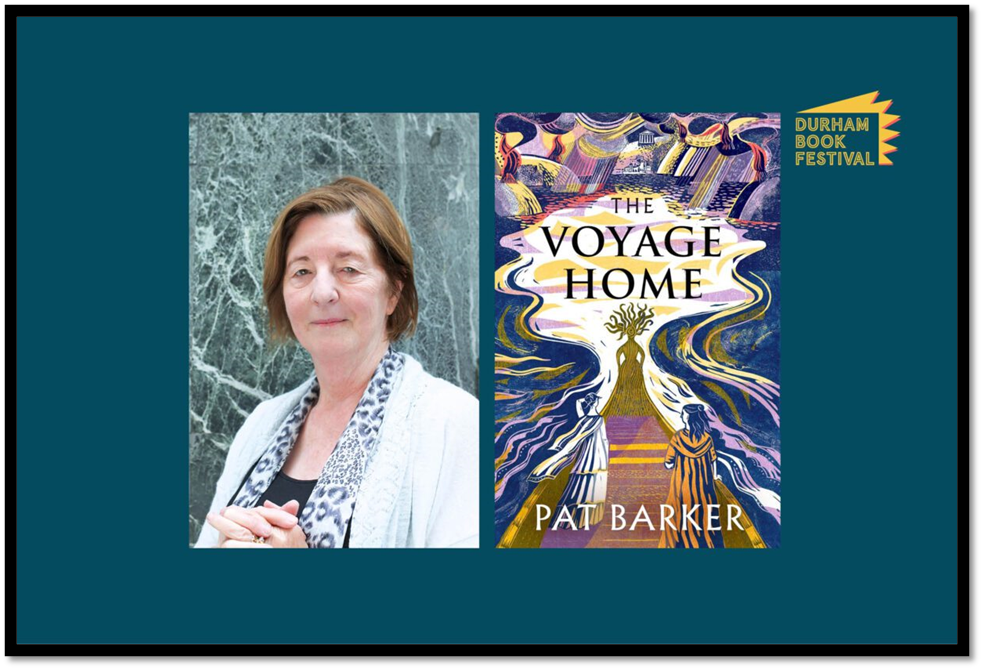

Pat Barker will be present at an exclusive dramatic live reading accompanied by new music from The Shining Levels on Fri 11 Oct 2024 8.00pm at The Gala Theatre, Durham . The performance will be followed by a conversation between Pat and writer Adelle Stripe, in which they’ll discuss The Voyage Home, chronicling the experiences of women in the aftermath of the Trojan War. I will blog about the event afterwards.

During the period over which Pat Barker has spun out her narrative of women of Troy, including the slaves that were the booty of its own wars, I myself have changed as I discovered when I glanced at blogs I wrote about the novels as they came out. Those blogs are linked to the earlier novels’ names here: The Silence of the Girls and The Women of Troy. Those earlier blogs consistently related to the way that Pat Barker has taken on the role of a novelist committed to fair representations of male queer life, but that is not the case with this new novel, which has new fish to fry.

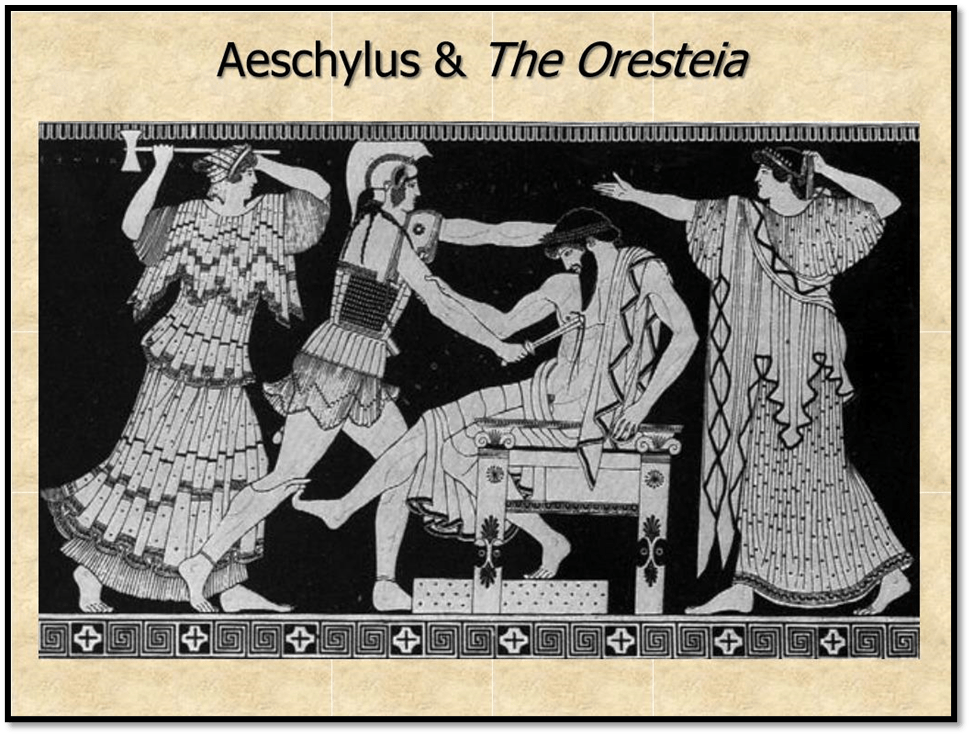

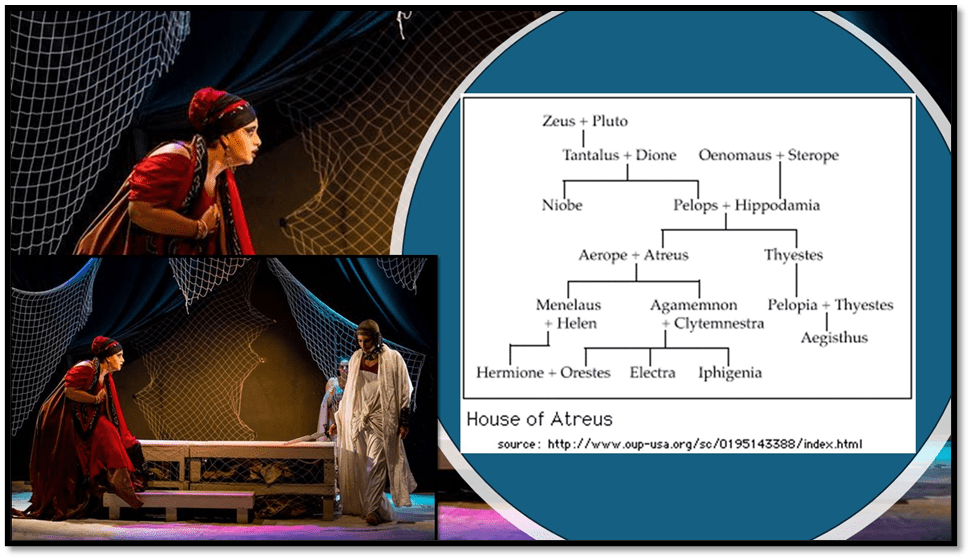

As noted by Fiona Sturges reviewing this novel for the i newspaper, Barker’s current series of novels cover the mythicised histories (giving the term ‘history’ a rather wide interpretation) that make up The Iliad but, of course, not only them. However, The Voyage Home owes more to Euripides (The Women of Troy in particular) and Aeschylus (the first two plays of The Oresteia in particular) than Homer. Sturges credits neither Euripides nor Aeschylus and indeed seems to suggest that the ‘source material’ for this story is entirely in Homer’s Iliad, which it is not. This is a deficit in any critique of the novel I hope to show even though Sturges does make a fine case for seeing the novel not only as at base feminist, which they are, but also compassionate for some kinds of feminist performative types, represented by Cassandra and Clytemnestra, that she, and her narrator, Ritsa do not really like. [2] Of this I have more to say later.

Claire Clark reviewing the novel in The Guardian makes good Sturges’ error about sources, although not thereby noting some of the closeness of the match of some of the storytelling (and imagery) to that of Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, the first play of the trio known as The Oresteia.[3] This closeness is so much the case that people may see Barker apparently adding what seem tonally contemporary details they think could not be in early Attic tragedy that are in fact already in Aeschylus. Take, for instance, the jokey summary of Clytemnestra’s exquisite rhetoric in welcome of her husband, King Agamemnon.

The context of that scene as told by Barker is that what is seen and heard [the speeches of the principal dramatis personae] is filtered through the handmaid Ritsa (Barker’s own wonderful invention). Ritsa is aware of just how far she has fallen socially since enslaved and names her current role, as other Trojan enslaved maids do, a ‘catch fart’, because these ‘body slaves’ must walk at that convenient distance behind their owner. We don’t catch all of Clytemnestra’s rhetorical welcome (any more substantially than we do any real farts emitted by Cassandra). This is so partly because, after Clytemnestra addresses Agamemnon as ‘Great King!’, ‘the crowd erupted’ according to Ritsa.

Ritsa, a plain Jane verbally, has little concern for great personages whose words puff themselves up, whilst the real work of living their grand lives is done by their slaves in service. She scoffs at Clytemnestra’s sense of duty as a Queen, to do and say the conventional thing, whatever the feelings of your audience. The phrase ‘though of course she did’ carries a lot of the suppressed disrespect that people of lower social function hold for those of supposedly higher function:

I mean, to be honest, she didn’t need to say anything else after that, though of course she did. A lot of it passed me by; I was too busy dreaming about cold water and rubbing my sore breast’.

When we do hear Clytemnestra speak it is with the metaphors given to her by Aeschylus in Agamemnon that cynically reveal the means by which she will murder her husband. She scoffs that he would, had he been as wounded in war as reports said, be ‘standing there in front of them with as many holes as fishing-net’. These words are a free translation of the Greek lines from Aeschylus’ Agamemnon lines 866-69.[4]

The august John Dewar Dennison and, on the latter’s death, Denys Page, in their magisterial 1957 edition of the Greek text, translate these lines of Clytemnestra word-by-word in an endnote. There they also quote another male authority, Sedgwick: “The cold-blooded phrase suits Klytemnestra’.[5] Men, of course hate strong women even in drama and that is what this commentary reveals. Ritsa treats Clytemnestra as no worse than any other upper-class bore with no idea of the value of others’ time. It is Agamemnon’s speech that she rightly turns her anger against, when Clytemnestra’s ends; not Clytemnestra’s like the long tradition of scholarly misogynists. Ritsa says Agamemnon showed no ‘generosity of spirit’ in a way that is a stab at the patriarchal commentaries like that above, which are the norm of Aeschylus criticism. Ritsa says of Agamemnon that:

He even managed to get in a concluding jab at Clytemnestra, whose speech had been, he said, ‘like my absence, far too long’. [6]

This method of reportage, as if Ritsa were audience of an event that passes as happening in real time but sticks closely to Aeschylus’ account of the mythical return story makes us aware, but only if we know the Aeschylus translated text or story in reading or in the theatre, that Barker is deliberately addressing the semi-fictive nature of the events recounted and their malleability to the Ancient re-tellers of the story. So malleable were they that widely different versions, even with differing versions of what happened, were produced.

Barker has, I think, chosen to stick closely to one account of certain events, like the homecoming of Agamemnon to the city, to ensure her own fictional additions, including modes of narration and details of less prominent characters, such as non-aristocratic women, of the Ancient courts, register on the reader’s attention.

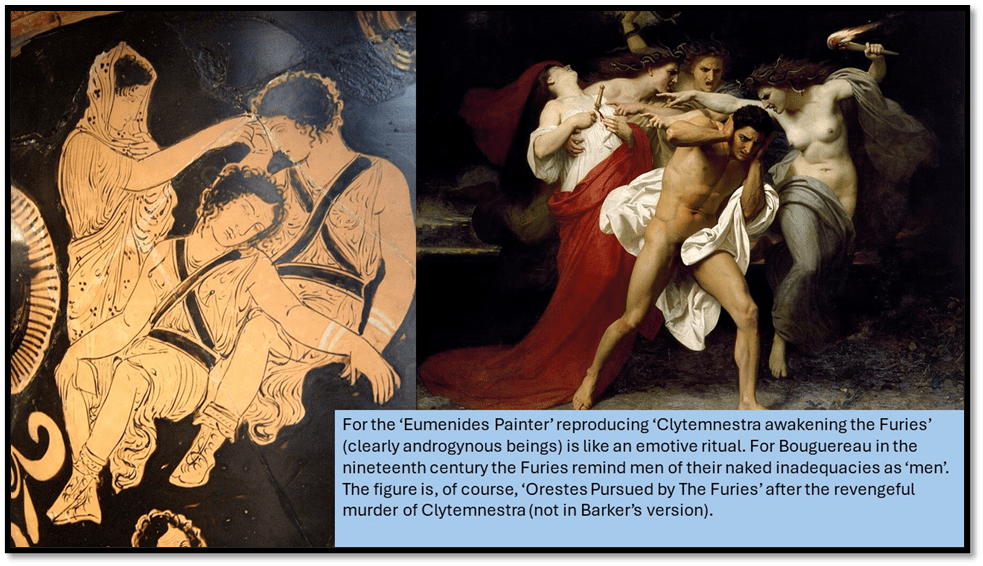

Barker’s additions in fact are attempts to capture the interior meaning of events as well as the events themselves, but that was the practice of the dramatists too. Notoriously, Aeschylus’s The Oresteia has always appealed because, unlike Homer’s Iliad where the interior lives have to be intuited and may be inappropriately intuited, it tells of happenings on the cusp of the intrapsychic and the external world. The classic example of its appeal in literary practice is T.S. Eliot’s The Family Reunion, but we might also cite Salman Rushdie’s Fury. Both texts use their own contemporary slant on the concept of the Eumenides or Furies ( Ἐρινύες [Erinyes] in Classical Greek). These beings inhabit the ambivalent sides of familial (or state) order or disorder respectively.

Pat Barker’s version appears to focus on this threshold of the uncanny, where familiarity and understanding is invoked in the mode of telling the story in order to query the grossly unusual events and sensibilities that respond to the events of which it tells. The Oresteia is, of course, the story of familial madness that turns upon the forms of a religion proud to bear on its face its irrationality. Of these features the Furies are the obvious symbol, though the myth also relies on the irrational vanity of Apollo as part of its explanatory equipment too. It is a set of three plays that invokes the nature of ‘madness’, as the Greeks viewed this, but is recognisable too in contemporary family theory, especially in our post-psychoanalytic Foucauldian century and Barker exploits both psychoanalytic and Foucauldian perspectives wittingly, or not, in her novel of the meaning of madness.

Hence, in this novel, childhood and familial experience cross (as I will explore later) with issues of both power and sexuality and encounter each other, often in external violence and/or the internal disorder of either the repressed depressed (notably in Agamemnon) or externalised ‘mania’ like unto ‘madness’ (certainly in Cassandra but perhaps Clytemnestra too). In both forms there is an encounter between internal and external worlds. In my title I quote from a moment when Cassandra awakes as the dominant point of view in a chapter set in the King’s bedroom on the trireme Medusa on its way back to Mycenae. Agamemnon has fallen on her, after much insensitive sex, lying entirely on top of her, such that she struggles like all of the great king’s conquest to find space to call her own – although this time it is only the space available on a ship’s cabin-bed, though it be the King’s cabin:

… Agamemnon’s fallen asleep on top of her, as he often does. Wriggling, she manages to free the fingers of one hand, … She waits, tries again, this time gets a whole hand free and begins to explore, a mouse venturing out in the vastness of the night. All she can see are purple and orange flashes on the inside of her lids, but they’re not real, they’re not like this patch of bedsheet she’s managed to recover – that’s real, that’s outside herself. Real, unreal; inner, outer – always debatable land to her. She can only marvel at the lives of others for whom these are clearly established undisputed borders.

And Agamemnon? How does he experience these things? Is he secure in the world of touch and smell? Lying underneath him in the dark, his fuck-sweat clammy on her skin, she finds it difficult to credit him with any kind of inner life. But he obviously has one. He sees his dead daughter. What’s that if not a disputed boundary? ’ [7]

When last did we read a definition of female oppression so comic and yet so precise. Lying under the literal sleeping, if not dead yet, weight of a man who professes his patriarchal power in every realm of the world – including his body, even his fuck sweat and in the very next sentence his ‘thickening’ cum, as well as his military and regal power to make slaves out of princesses and coerce them to his will, even in sexual service, Cassandra fights in debatable land’ on the border to exert some little influence.

The term ‘debatable lands’ is a strong one for a writer from County Durham for the county once was one between Scotland and England if not as much as the long known lands of this name just north of Carlisle in present-day Cumbria. But the point is that there are ‘debatable lands’ between other supposedly defined entities and binaries than Scotland and England, ones between male and female consciousness, the world of the external senses and inner words where what is seen and felt may not be there at all in physical form, a haunt of ghost and other embodied memories, reason and imagination and, of course, the real and unreal.

Cassandra is a ‘seer’, the pupil of Calchas who appeared in the earlier novels. The Greeks knew such persons, the most well-known being Tiresias, by the term “mantis” [μάντις (mántis)] meaning “soothsayer” or “prophet”. Whether Cassandra is a’ prophet’ of future events is a moot point in the novel as her denial of a coming storm that every worthy sea-person knew to be coming, and did come, shows. Yet her central vision of the bloody death of herself and Agamemnon at the hands of a woman does come true, although Cassandra herself manipulates the situation in researching Agamemnon’s bathroom preparations as devised by Clytemnestra, involving a ‘net’ and an early straitjacket designed by Clytemnestra herself.

Both Sturges and Clark, critics I have mentioned before, see the central point of the encounter between Cassandra and Clytemnestra (Sturges sees it as an echo of the imagined meeting between Elizabeth I and Mary Queen of Scots to decide, under the radar, whether they are ‘rivals or accomplices’) as an examination of two kinds of powerful woman, powerful in different ways. Cassandra is attached mainly to the inner world of religion and the sexualised divine (Apollo spits in her mouth to ensure the divinatory powers he gave her with a kiss will be believed by no-one). Clytemnestra is attached on the other hand mainly to the outer world of power, riches and the determination to enact the same role a man would play, however impossible her patriarchal society makes this.

Once Agamenon is home, the Queen’s advisors desert her – her power is quashed. Clark says that Barker creates a ‘shrewd and capable ruler’ and capable mother (at least one that tries hard against the father-fixated children she bore Agamemnon) in Clytemnestra., whilst the ‘yellow-eyed Cassandra’ is ‘unlikable’ and made so by Barker. She is a woman determined to prove by her own story that all women are victims of male power. In effect I think Sturges correct in that in both depictions Barker shows ‘immense compassion for the women she depicts’ – even the ones men see as monsters, even and especially Medusa.[8]

However, in my view both of these women, though loved and understood, when they allow themselves to be seen as they are (less so with Cassandra), are polar examples of rogue forms of what calls itself radical feminism in the twent-first century and which differs from the practical thoughtful respect for women’s selves and value in Ritsa, the slave narrator. Cassandra wants to see herself as the iconic female victim and aims to precisely become that – a kind of J.K. Rowling, I think. From the beginning Calchas sees Cassandra as a ‘sacrificial goat; her ‘yellow eyes’ ‘reminded him of a goat’s eyes and he says that she had the same numbed look of a sacrifice’.

Ritsa sees her as having the potential to be ‘the eagle with sunlit eyes’.[9] And Ritsa would make her so. She alone refuses to see her as a ‘victim’ on her death, for it is, Ritsa going through the motions of religious services for the dead overlearned by all women under Greek hegemonic power, feels fear of the consequences of the death of Cassandra, but also some genuinely feminist anger against that model of feminine life-performance she was. She says:

Most of the time I just felt angry. With the gods, yes, obviously, but mainly with Cassandra, who I still thought could’ve lived if she’d wanted to. Perhaps that wasn’t true; perhaps she was doomed from the moment Agamemnon said he wanted her to share his bath. But no, she’d wanted to die; she’d chosen death and she’d got what she wanted![10]

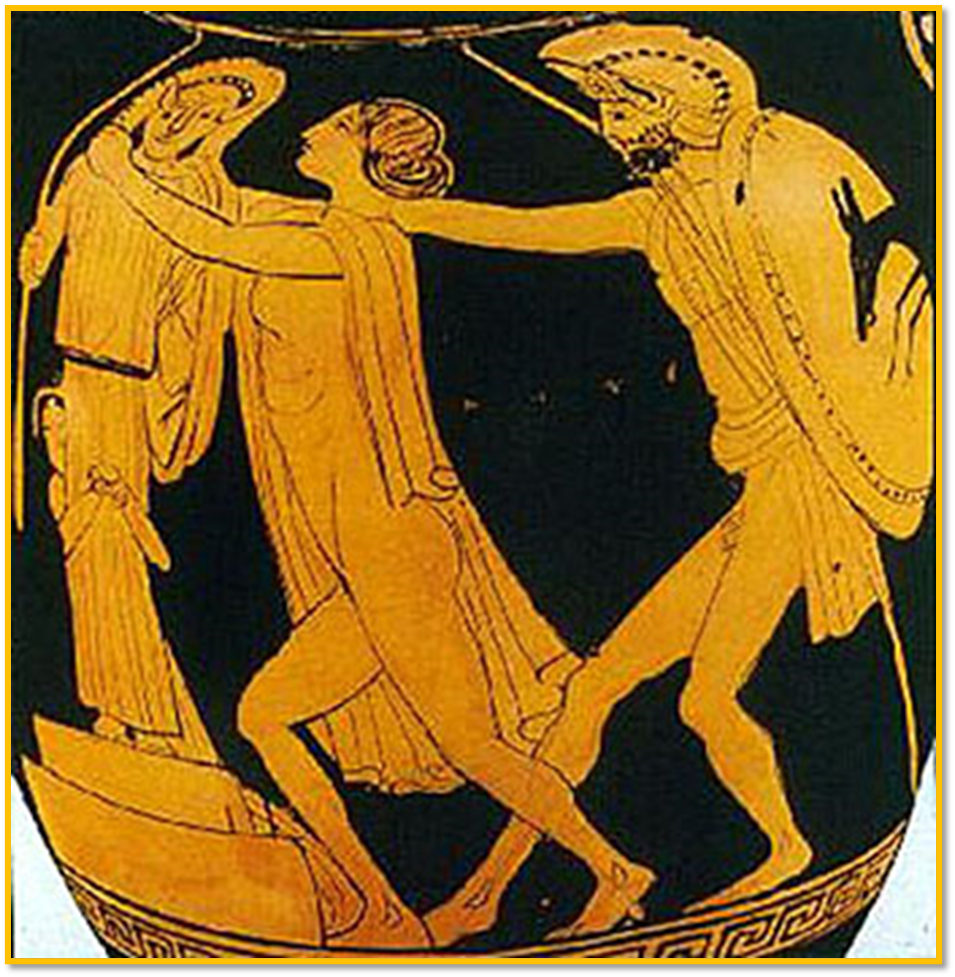

This Greek vase presents Cassandra’s death as a rape

At no point was she doomed by prophecy, though Ritsa admits that Agamemnon’s determination to have sex in the bath with her in front of his wife possibly ‘doomed’ her, but even then Cassandra knew the instrument of her death would be a vengeful angry woman, Clytemnestra. The latter gives Cassandra an extra unnecessary cut to kill her baby, another orifice in a hated woman, to express her jealousy through the death of the prophet’s unborn child, as Ritsa realises.[11]

Cassandra dies by Agamemnon’s sword, in fact the sword inherited in patriarchal fealty from his father Atreus and this matters, but no less than the fact that the sword is borne by a woman. Clytemnestra is another of the bipolar images of an irrational male-inflected ‘feminism’, not based in ‘victim-ideology’ as Cassandra but the avenger who takes on the role and weapons of patriarchy. In this novel, unlike Aeschylus’s, Aegisthus, her lover and also part of the house of Atreus line (another son of Thyestes) is there to supply the male militias he controls – yes – after the event of a legitimate King’s death, but also to be a foil to Clytemnestra’s manliness claims. When Aegisthus claims he should be the one to kill Agamemnon because “fighting comes naturally to a man”, Clytemnestra says, with Barker’s full agreement I think but with a well-chosen word of refutation for the woman concerned: “Bollocks.” When Aegisthus say in reply, “Exactly” and Clytemnestra (for the story here is from her point of view) admits: ‘By his standards that was almost clever”, the stall on which Clytemnestra’s assumption of bollocks for herself has been set.

Clytemnestra is a driving avenging force against patriarchy in every one of its embodied icons and material symbols but especially the phallus and balls. When she straitjackets Agamemnon and then nets him, she has him at the mercy of death by his own sword – and the symbol of that with which he fucked the pregnant Cassandra in front of his wife, raising her ire further. At his death, Agamemnon bears the sword of his father, Atreus, the man who had killed and butchered, for their father Thyestes (Atreus’s brother), his own cildren to eat. The phallic sword symbolises the patriarchal line, although it had also been used by Agamemnon to murder (or sacrifice depending on how you see it) his own (and Clytemnestra’s) favoured daughter, Iphigenia. Clytemnestra milks the feminist drama here for all its worth as she stabs Agamemnon, and we see his dawning awareness why:

… Only when he sees her pick up Atreus‘s sword does it start to make a kind of sense, the kind that cooks children and feeds them to their father.

“Look.” She’s holding the blade in front of his eyes. “look, darling,” she says again – the same demented cooing sound – “Daddy’s sword”. Do you remember what Daddy’s sword does?”

,Daddy’s sword’ as well as being the implement that sexually subjugates, symbolically at least also kills the children it fathers, especially girl children but not only those. Here is the venatrix armed with a phallus and a net as all good masculine goddess ‘huntresses’ (the model being Artemis) should be. Barker understands what makes women choose Clytemnestra as much as Cassandra role as ‘feminists’ – it is patriarchal ideology mistaken for biology that regulates the training of adults, but she prefers a rational feminism – the kind of Mary Wollstonecraft, the Unitarian Harriet Taylor (the real power behind John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women) and Margaret Fuller.

Mary Wollstonecraft, the Unitarian Harriet Taylor (the real power behind John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women) and Margaret Fuller.

That both models of patriarchally skewed feminist paradigms, is shown by the fact that Cassandra and Clytemnestra, are both irrational women – ‘mad’ one could say, where we mean anger turner into irrational symbolic forms and passing as a way of life. Their model is Medusa, which is the name of the ship that carries Cassandra and Agamemnon to the port serving the polis of Mycenae. I see Barker’s feminism in the mode of that as yet not fully appreciated in A.S. Byatt and indeed I think this novel references through Ritsa, Byatt’s volume from The Frederika Quartet, namely The Whistling Woman.[12]

The illustrator of the cover of Barker’s book, Ellen Warner, has obviously too picked up the ways in which Clytemnestra is based on the paradigm of Medusa and made her power radiate out like the venom of snakes passing as a hairpiece.

Medusa, of course was the symbol in Freud of the irrational fear in MEN of the supposed power of the female genitalia to turn men to stone (the meaning of hardness being the obvious common denominator of the symbolic transference) and to overwhelm and castrate them – the theme of the vagina dentata in psychoanalysis. That is why the novel tames Medusa eventually. As a ship, the Medusa is well named thinks Ritsa because it jerks her about by its ‘sudden movement’ to and fro. [13] Seeing the figurehead of the Medusa as the woman’s head after whom it is named, Cassandra jousts with the man who owns her about Medusa being called a ‘monster’ only because men favour an ‘objectionable little prick’ (another joke) like Perseus to be made the ‘winner’ with the right to ‘monster’ his victims.[14] Eventually Cassandra is moulded by her intent toward death as a ‘second figurehead’ like unto Medusa herself.[15]

Ritsa’s feminism, as that of the rational but power savvy women (mainly slaves rather than enduring aristocrats) of the earlier novels, is about the understanding of unequal structural divisions of power, that covers class , sex/gender and race. It bides its time, undermines dramatic protestations of male power, notably in the enormously ‘thick prick’ (for once the term which is a terror otherwise, applies) meet with the end they have unwittingly courted but of which, in their narcissism they felt themselves immune.

Barker does have sympathy for Agamemnon, precisely because he does have an inner life, entirely absorbed by the daughter he sacrificed. The latter pleaded with him as her ‘Daddy’ as she was murdered by Atreus’ sword at Aulis (as Euripides tells us in one of his plays although in another she escapes murder with the help of Artemis and becomes her priestess). But essentially the madness of patriarchy, that infects Cassandra and Clytemnestra to such degree that they still feel ambivalent about him, is embodied in him and his psychotic visions of a daughter he abused.

We need however, in considering Ritsa’s feminism to GET BACK TO THE FURIES! The issue in particular that Pat Barker emphasises in this tragedy is the fate of children in the hands of men of power, or women acting as their agents. The fall of Troy is more focused on these victims than of women as in the last two of this series of novels although it tries to take in special acculturated link between women and children too into its remit. The fate of Andromache’s son, Astyanax (Cassandra’s nephew) from Euripides’ Women of Troy is there but only to indicate that he was one of the many genocidal child deaths associated with Greek settler colonialism, as with Israeli settle colonialism: my mind keeps shifting to Palestine as I read, for there are useful analogies in the situations described, for those exposed to such dread conflicts only from afar.

Children in this novel are subjected to the physical, psychological (the source of Electra’s eczema), sexual and other appetitive murders in this novel (direct of course from the Greek myths). Children are subject not only to the violence of family, the internal management of political states’ that foster child poverty (especially under exploitation of its human resources or colonial settlement) and in international conflict. One of the most haunting new features of this novel is it borrowing a symbolic device from T.S. Eliot, and perhaps his his source too, Kipling’s best short story They.

In this story guilty men hear the sounds, and sometimes see the ghosts of their shared children in whose death they were collusive, sometimes distantly. The Furies in Barker’s novels are the voices of children – whether those of Thyestes in the walls of the Palace of Mycenae, or echoing from real children at play or seen in footprints or hand-prints of children who are not ‘real’ but still there, projected by adults into the walls that represent their adult duty of defence and safeguarding, a promise to children rarely kept. [16]

Women rightly want vengeance, but cannot do it by dramatic and personalised witchery, as Ritsa realises as she thinks of the losses of the ‘women of Troy’ at the end of the novel.[17] They want revenge for their children but also ‘for their own suffering, for spoiled hopes’. And this is a just cause. The problem with that specialised revenge built on powerful iconic models is not enough, for in this set of stories in the novel:

Justice. Revenge. Call it what you like, it turned out in the end to be a prerogative of the rich and powerful’ The best those slave mothers could hope for was survival – and not all managed that.[18]

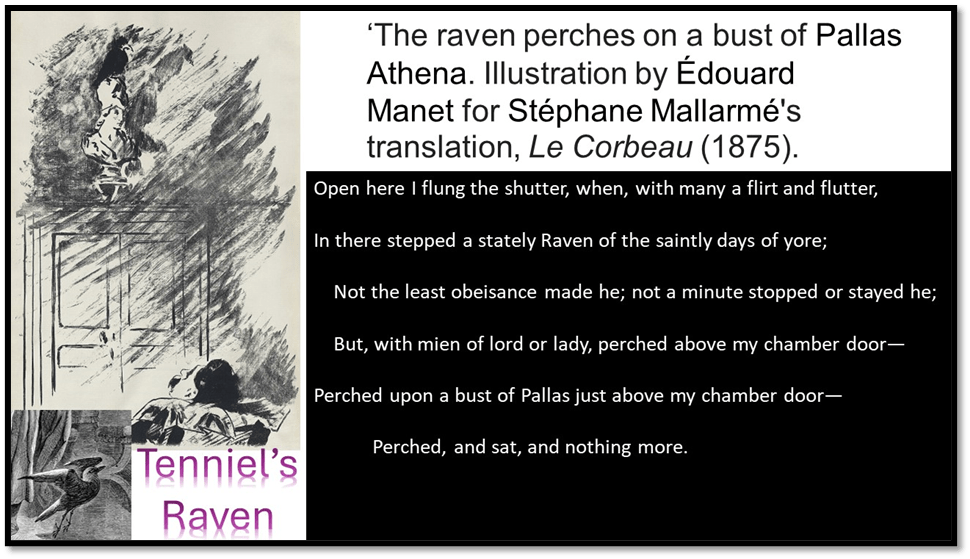

The children, yes those of Palestine too, must be avenged but not by the powerful political voices trading murder for murder, but with a genuine basis for human survival. That is why the children sing haunting rhymes about suppressed violence to remind adults of how they are acting, often the ‘chopper to chop off her head’ is invoked but not only that rhyme. Ritsa hears the Furies as children pleading but not in madness and anger but in a means of strengthening ways of achieving social justice. In men, the Furies take on mad forms – not quite yet in Orestes in this novel, unless there is like to be a sequel (and why not), but clearly in the mountainous depression and violent outbreaks triggered by the psychotic vision of Agamemnon. Sometimes the interest in and meaning of the Furies is seen in this novel in ravens as in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven, for there are ravens a-plenty in it.

But though Ritsa toys with male fantasies that ravens are the Furies, she is too rational to think that for long. To blame ravens is yet another excuse men make for bad governance of women’s lives, as with Poe’s lyricist with regard to the life of Lenore. Sick of the flowing fantasies of caring for Cassandra’s yellow dress, Ritsa seeks fresh air but finds only the visceral lives of palace slave servants butchering animals for food and sacrifice (the two weren’t distinguished in Greece). There she sees ravens such as Cassandra and her male friends have blathered on about as the symbol of Furies:

Piles of intestines stinking in the heat and, gathered in a circle round them, jabbing and darting and squabbling, were the black birds I’d seen earlier on the roof. There’s your Furies, I thought, obscurely pleased by how craven and squalid they seemed, how utterly devoid of the meaning Cassandra had attached to them.[19]

Barker chooses to vary the story by the use of Furies that really are animals who act like the men who as warriors and power-seekers act like predatory or carrion animals. Except some women think the answer is to become toxically masculine. They are never that simple though and that is why Barker, if not always Ritsa, is fair to Cassandra and Clytemnestra as well as demonstrating their irrationality.

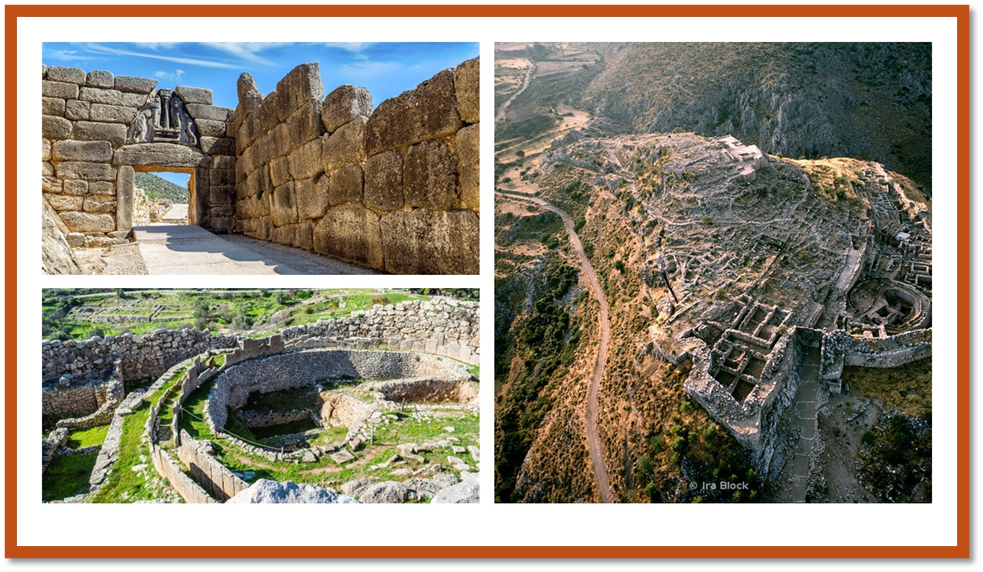

I have, I think, said enough, except to point out that the way in which the palace of Atreus is psychologised by Aeschylus in Agamemnon is unpacked as a product of strange male symbolic architectures in Barker that are ‘real’. Unlike Aeschylus, Barker has clearly trod round the hot ruins of Mycenae as I have. It has been, unlike the Mycenaean architecture of Minoan Knossos (over-exposed by Arthur Evans), carefully excavated with many of its dark passages leading to infernal depths (or so it seems) retained. Its magnificence is also a physical constraint, its ‘labyrinth of corridors’ conducive in their darkness to fantasy of self-loss.[20] Everything is smaller than the grandness you expect, even the ritual lustral basins – the baths in which Agamemnon meets his end. But we see here that the small mindedness of power was a material thing for Bronze Age Greeks. Even the Lion Gate, seen often in the novel, is smaller than expectation. Barker absorbed that and realised how else could one think but in near-Gothic insanity in such circumstances. This is a book that still puzzles in the ‘debatable land’ between the real and the unreal, as in life we all have to.

Do read the book. It is wondrous. Her best yet. I will report back on the Durham event.

With love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] Pat Barker (2024: 44; 45) The Voyage Home Hamish Hamilton

[2] Fiona Sturges (2024: 42) ‘Female-focused Iliad comes to an end’ in the i newspaper (Friday 9 August 2024), 42

[3] Claire Clark (2024: 51) ‘Parting the veil’ in The Guardian Culture Supplement (Saturday 10th August 2024), 51.

[4] Barker mentions a ‘fishing-net’ that is imported into many translations (by Richard Lattimore for instance) when a land-hunting-net could as easily be as intended and was as common. Robert Browning, I think, probably gets it right:

And truly, if so many wounds had chanced on

My husband here, as homeward used to dribble

Report, he’s pierced more than a net to speak of!

[5] Cited John Dewar Dennison &, Denys Page (Ed. 1957: 144, note to 866 ff.) Aeschylus Agamemnon, London, Oxford University Press.

[6] Barker 2024, op.cit: 142. This references lines 315f. of the Aeschylus.

[7] ibid: 44f.

[8] See Clark op.cit & Sturges op.cit.

[9] Barker 2024 op.cit: 1

[10] Ibid: 266

[11] Ibid: 254

[12] See ibid: 151

[13] Ibid: 55

[14] Ibid: 64f.

[15] Ibid: 107

[16] See ibid: 122, 158, 170f., 179, 210, 227, 286ff.

[17] Ibid: 283

[18] Ibid: 284

[19] Ibid: 168

[20] Ibid: 157

2 thoughts on “‘Real, unreal; inner, outer – always debatable land to her. … He sees his dead daughter. What’s that if not a disputed boundary?’ This is a blog about Pat Barker (2024) ‘The Voyage Home’”