Steve Harvy seems a good guy and he has given an opinion of Sir Thomas Browne’s prose style that seems to sum up, quite fairly I think, the way literary thinkers view that writer’s work in the light of contemporary prose writing fashions. [1] Urged to push that Faber published Sir Thomas Browne’s work, even T.S. Eliot replied that:

…. the question of a selection of passages from Sir Thomas Browne has been discussed by my Committee, which was unanimously of the opinion that such a volume was unlikely to have any prospects of popularity.… [2]

Eliot was writing in the 1930s, when Browne would still be taught in schools. Even in the 1960s when I was at grammar school, that school still held in its English Department store copies of Browne and Spenser, though by then there was no hope of either being taught at O or A level. I wondered why then bought recently a second hand copy of Browne’s works:

Harvy makes the point that:

Sir Thomas at times wrote in a lurid purple prose which has long since gone out of fashion though some later writers have been able to imitate and extend it, e g Thomas De Quincey in the three part account of his drug addiction and Melville in Moby Dick. … In general, purple prose runs the risk of bombast and embarrassing pomposity.

Fair as this might be, I hate the term ,purple prose’, though it was stock in trade of teachers of English writing in the 1970s, who still held Ernest Hemingway as the model of the perfectly cut-back prose sentence. Harvy goes on to say that Brown must be kept in his place as an example from a history we can, if we wish, decline to visit. As I read what follows, I remember that the term ‘Baroque’, and more so ‘Rococo’, were ones borrowed from art history merely to point out that writing was unhelpfully florid. Yet Harvy is better than that. He says that writers like Browne (and he includes most of the well known English prose essay writers up to the eighteenth century) actually wrote using the equivalence of visual chiaroscuro and foreshortening, a means of emphasizing the painter’s selection of focus by evident manipulation of light, dark and shadows, as in the developing enclosed theatre-houses of the seventeenth century.

The canon of Sir Thomas’ writings can be best appreciated in the context of the seventeenth century which was the age of Baroque prose. The prose of the late sixteenth century e g Sidney’s Arcadia and Lyly’s Euphues, had been highly mannered and contorted. These writers as well as Shakespeare in the prose parts of the plays were influenced by the Italian, Spanish, and Dutch painters (including Michelangelo and El Greco) who thrived on the distortion of form whereas the early Baroque painters like Caravaggio and Rubens restored the integrity of form. The prose writers of the seventeenth century – Bacon, Burton, Taylor, Donne, Milton, Browne, the early Swift, Pascal, Descartes, Moliere – likewise aimed at three dimensional effects. They used the verbal equivalent of foreshortening and light and shadow.

This is a useful idea, although it still requires us to consider the vast difference between the visually scenic and the writing of embedded prose units in hierarchical structures that foreshorten the temporal relationship between the actin in main and subordinate clauses. The periodic sentence is another term often merely for the long sentence, but that misses out its complicity with the effects of duration. By the last phrase I mainly refer to the psychological components of response duration involved in reading such a sentence – endurance, attentive waiting for meaning, the feeling of suspended flow and the retrospective decision making that untangles a main clause or conjoined (using a conjunction like ‘and’) main clauses from ‘subordinate’ clauses in a single sentence. Of course Milton was the master of this, especially in verse, though he bowed to examples, particularly from Shakespeare’s later ‘romance’ plays.

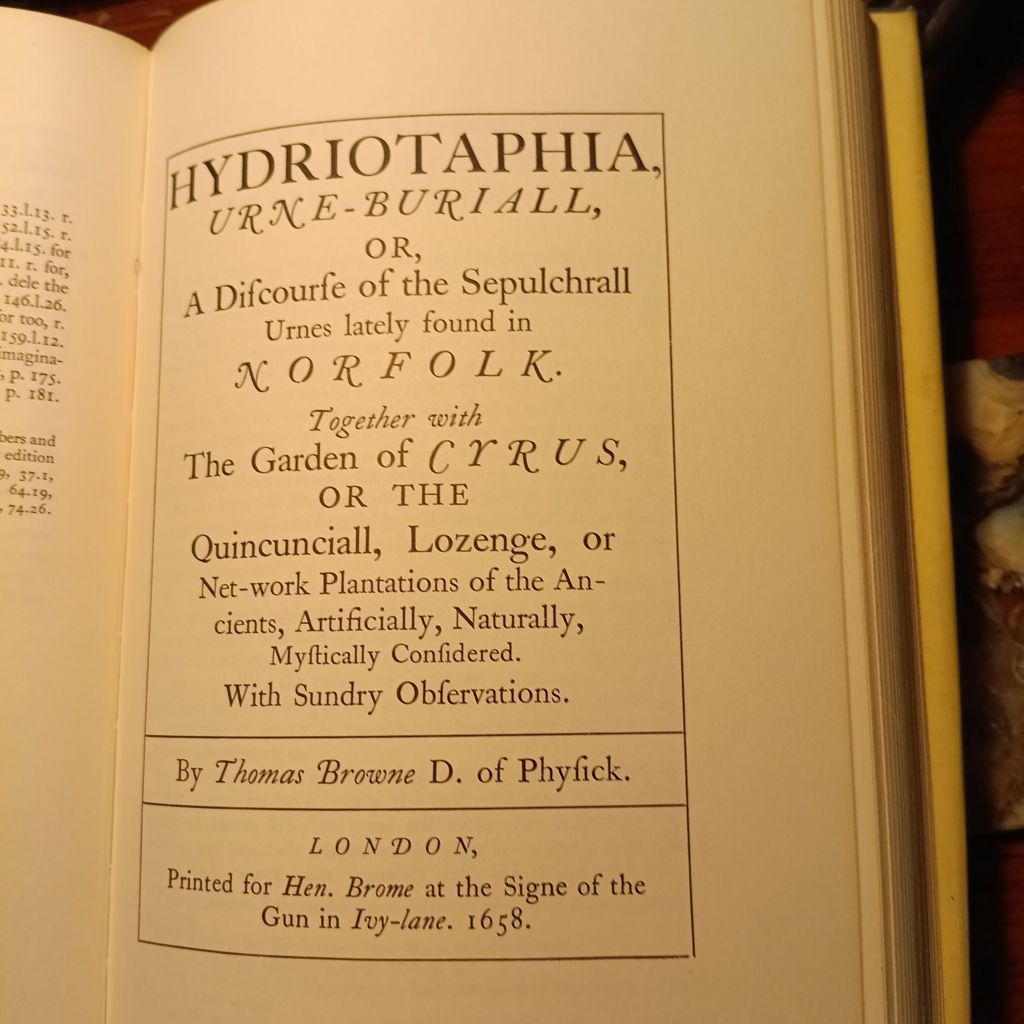

But this blog is just on Browne, and all I intend to do is to take one sentence from him to examine: from a work once taught in schools, Hydriotaphia, Urne-Buriall, or, A Discourse of the Sepulchrall Urnes lately found in Norfolk.

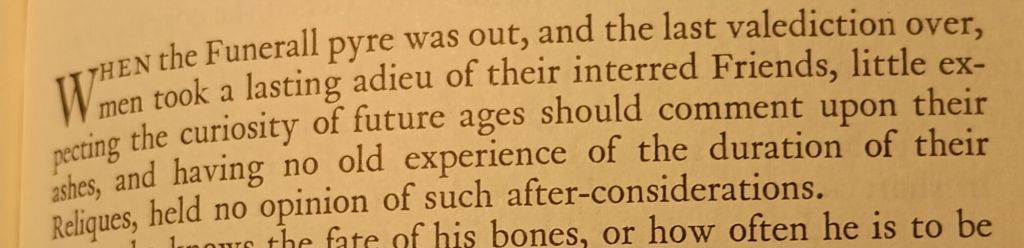

The title alone puts off many, so what of the first sentence, which is also the first paragraph of the work, which I take as my example – not the best by any means of such phenomena, but , like any beginning, it is a good place to start.

The main clauses of each half of the conjoined sense units in this sentence are governed by the same nominal syntactical subject, ‘men’: men say goodbye to the friends they witness buried (a straightforward record of the event) and also could not hold any view that their friends remains would persist in the longue durée , given that they themselves will not see out that time in which a large succession of lives will give way to each other (a more complex reflection on human psychology). I plead with any possible reader will look kindly on my attempt to reduce Browne’s sentence to the many stated and implied messages within it for periodic sentences relish the complexities embedded in them. This sentence depends on the sense underlying it that mortality and endurance are concepts that only have meaning for people if they think not only about events as they relate to them immediately but to people across vast spaces of time in which they themselves will be forgotten and not known and about whom they are unlikely to think. Yet the sentence is about remnants of lives that outlive he original significance of lives – those commemorated by the surprising finds of funeral urns in the ground at Norfolk containing ashes of persons about whom we know little but that they died a long time ago.

A long periodic sentence wants us to realise the psychological experience of how meaning is subject to temporal processes, even in the very structure of the sentence and an ability to make interpretive connections – the type of connections that understands that subject of the verb ‘held’ is still ‘men’, but ‘men’ we have now to think about differently from those stood at a friend’s funeral. They must know be seen as men who illustrate a truth that they are unable to be conscious, for they cannot retrospect on the live so long after their’s that it is unthinkable. It is unthinkable but a periodic sentence can invoke it precisely because its meaning are based in the manipulations of perspectives of events, not available to their syntactical subjects. In face being a conjoined set of clauses ths sentence is less complex than periodic sentences that avoid simple syntactic conjunctions.

Browne is worth studying because he knew how to vary not only meaning but attitude or tone over a sentence, such that they contain playful ironies, sometimes verging on creating laughter around topics thought improper to be laughed at. Take this sentences that turns to ridicule the claims of religion to on its own overturn the effects of profane time by spiritual significance and mission in the long dead, in this case the prophets of Christ’s coming in the Old Testament who are inscribed in the New to return at the Second Coming of the Christ.

Enoch and Elias without either tomb or buriall, in an anomalous state of being, are the great Examples of perpetuity, in their long and living memory, in strict account being still on this side death, and having a late part yet to act upon this stage of Earth.

A modest example, this sentence takes on the meanings that interpret the time scale of the God of Christianity in the role of the Two Witnesses, Enoch and Elias (Elijah) of Byzantine Christian tradition and casts it into periods, where clauses suspend direct movement through the sentence, disrupt progressive motion through the sentence, and cause controversy by seeing ‘Examples of perpetuity’, a grandiose term highlighted by the capital ‘E’, as, in a more sceptical consciousness, ‘an anomalous state of being’. But perhaps it is not controversy because Browne knew the role of Enoch and Elias to be an anachronistic problem in textual scriptures, the source if this duo being apocryphal (mentioned only by the non-canonical Nicodemus).

The physician Browne reminds us that in ‘strict account’ these men must still be alive in order to have a role in the future Apocalyptic times. You ought, you must, notice how Browne takes a rise out of this Byzantine mummery just asin the sentence before he does this with Saint Gordianus, the Byzantine Saint murdered by Julian the Apostate, brought back to English soil where no-one knew where to bury him. Browne is a fascinating writer. The periodic sentence needs him but it had in later times George Eliot, Henry James and latterly modern writers have stopped despising it, though it is no longer the staple fare. It offers a form to thoughts, especially about human experience in time you can find nowhere else.

Of course, without the periodic sentence how would I fill my days, brought short by being held in the vault of knowledge and skill thought as useless in modern times, without their internal music to invoke, the counterpoint of differing clausal harmonies being my music of the spheres. Well, you could write simply? asks a voice tentatively. What? Is there no longer a beautiful periodic sentence enshrined in stars for old fogeys like me.

Bye, bye, my loves

Steven xxxxxxxxxx

_____________________________

[1] a blog available at https://www.sirthomasbrowne.org.uk/thomas-browne-blog/about-sir-thomas-brownes-writing-an-opinion

[2] From a search on the site holding an srchive of T. S. Eliot letters: https://tseliot.com/letters/search/person/Cuthbert%20Harvard%20Gibbs-Smith