Talbot Rice Gallery, aided by the artist, this year shows us the continuing newness and vitality of the work of the artist El Anatsui for the Edinburgh Art Festival. This blog interrogates the exhibition with the help of Susan Mullin Vogel (2020) El Anatsui: Art and Life Munich, London, New York, Prestel Verlag. It concludes I need to learn more, and see more, of this artist.

Mullin Vogel’s 2020 work on El Anatsui has updated lots of the concepts that critics have used in the past to describe the work of El Anatsui whether concentrating on the use of a new medium in art or his reference to Pan-African themes. These critics include, she tells us in this edition of her book, herself as she first thought and wrote about this artist in her 2012 first edition of this very book. The 2020 edition is a complete revision of El Anatsui in every sense of the word, not only adding reference to works in the period up to 2020, but also rethinking the meanings attached to his work and working methods. She does so in the light of the artist’s emerging practice and the way he increasingly speaks about his practice.

The book has on its cover a towering monumental work that appears as the guest at the Talbot Rice, on loan from its commissioning owners the Royal Academy of London. It is so hard to miss I referenced it of course in my blog on my schedule for the day in Edinburgh (available at the link for light relief if required) wherein I saw this work. There I refer to it thus:

As you leave you have to see the huge 2013 work TSAATSIA – Searching for Connection, which mimes both cartography and landscape and yet references colonialism throughout …[1]

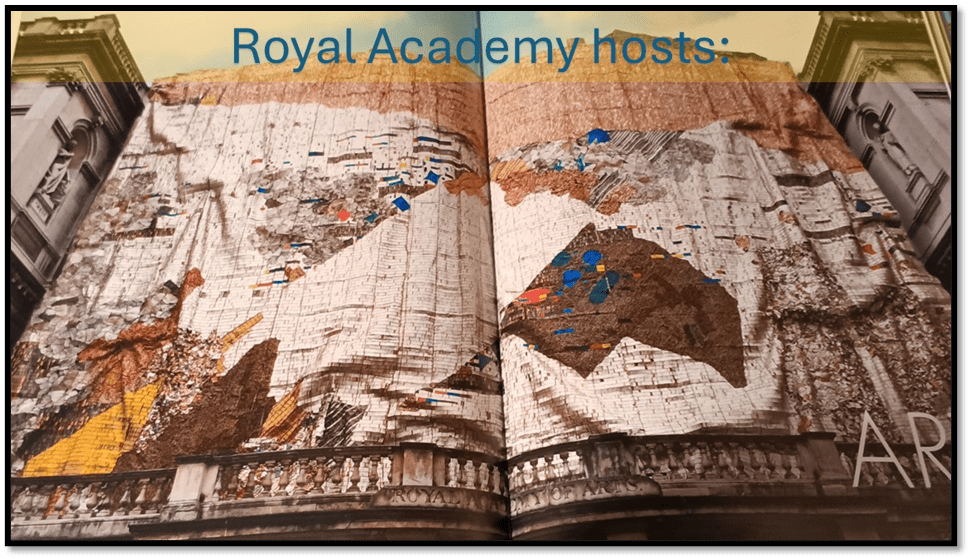

But even, and perhaps especially this work has not stood still – in more than one way. Here it is, from a full section title page in the book, which shows it in modern ‘monumental’ grandeur, responding to the monumental grandeur of a more static kind of Burlington House, the home of the Royal Academy near Piccadilly in London.[2] In her book Mullin Vogel calls TSAATSI-Searching for a Connection, ‘arguably, the greatest of all his works’.[3] It was on its installation moreover in May 2013 ‘one of the most visible artworks in London’.

Mullin Vogel contrasts its intended place of hanging to the ‘modest space’ in Nsukka in which he and his assistants crafted the piece, a low-lying bungalow structure in which the piece was made up from sections and then assembled and bound together from, at that point, eight huge sections, using a stitching technique employing metal wires, in situ at the Royal Academy over a stressful weekend. As it grew, over the period of almost a year of its creation, to its full size of 4,000 square feet, the work could be rolled in temporary storage and in waiting for transportation, making the point that it is an art, however monumental in appearance on a Western venue of colonial proportions, was born from the idea of an art that was communal, nomadic or migrant in its very conception, designed to be moved to other spaces.

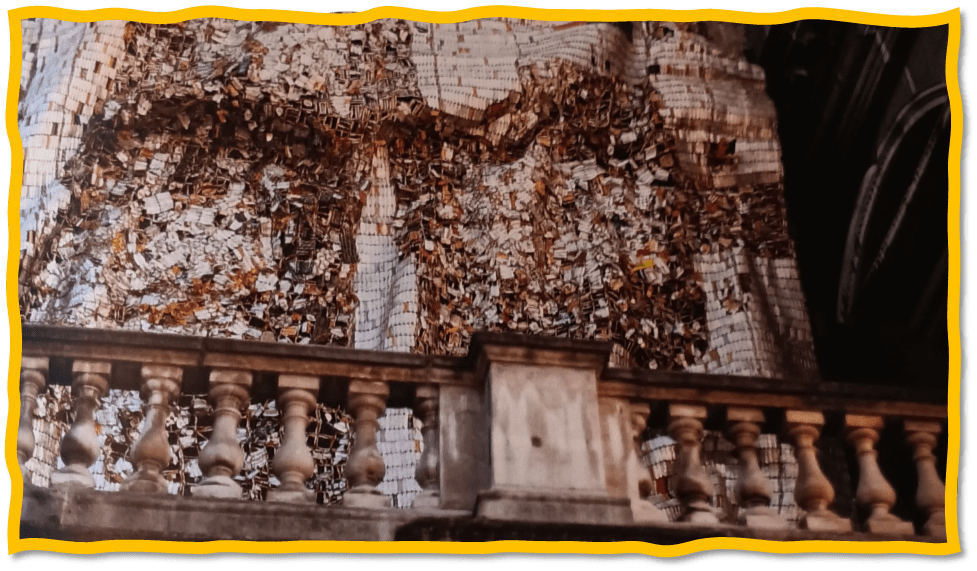

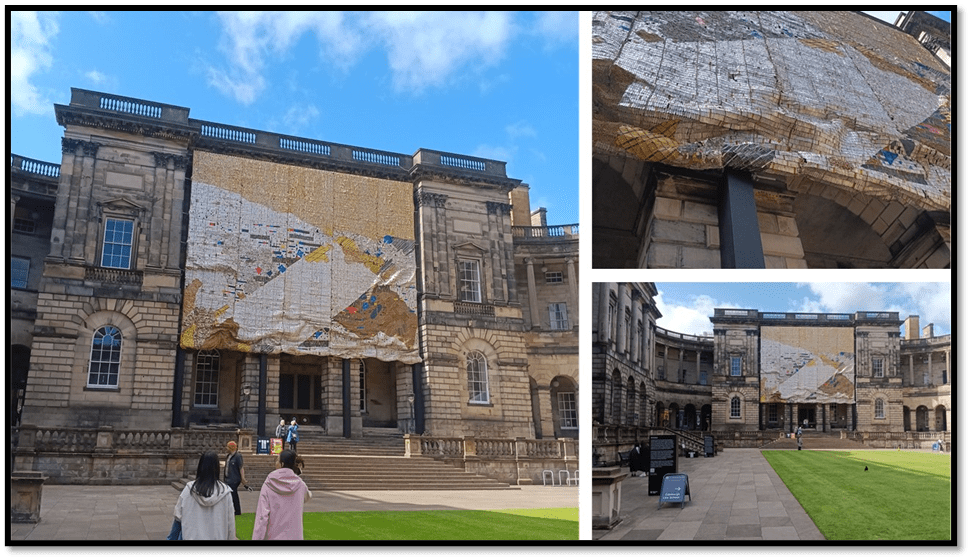

There is however some family resemblance to the Old College venue, both resplendent versions of a rather Baroque version of Classical-leaning architecture. The similarity in the building structure – the piece hanging between the towers fronting the facia that itself looks down upon approaching spectators in their courtyards. The work is about travel through space. It has the look of a landscape representation (‘a vast fantastical terrain’ in Mullin Vogel’s words) across which some huge mobile object or mass is moving, meant to signify the liberatory role of huge migrations on an Africa over-regulated by past colonial administration.[4] However, this motion was conveyed by images that were relatively static in real time and space. There could be some motion given that movement is always possible in these ‘stitched’ metallic sheetings and the idea of real time motion would also be conveyed by the passage of diurnal and seasonal lighting effects in real time. The sheet at the Royal Academy however rested on the building’s architectural features. It may show on its facia the effect of a cascade by virtue of the shimmering relief of multicoloured bottle-tops that, one could say, flowed at its lowest craggy portion apparently onto the floor of a Baroque upper storey external balcony. Looking we might even expected ‘overflow’ from that balcony imaginatively. There is a photograph of this effect in Mullin Vogel[5]:

But take a look again, If you have seen my earlier blog, at my collage of photographs of this work as it appears in the Edinburgh Old College Quadrangle.

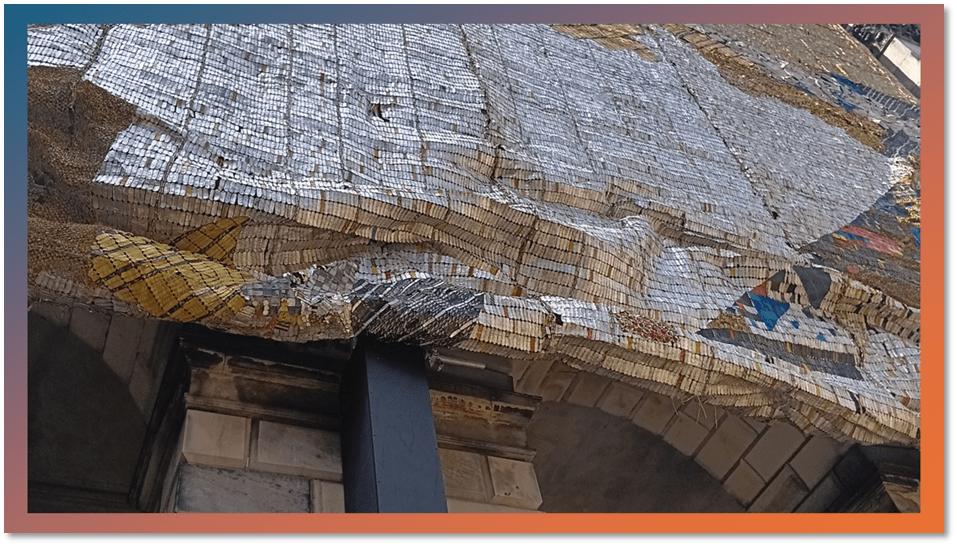

Of course this work falls, when it fully does so, only to the columned portico across the front of the building facia. Any visitor (and many come only to see the college architecture) may pass at this level, the lower level of the work itself, unlike the situation in the Royal Academy. Moreover, clearly in photograph reach all the way to the flooring, nor can I testify to the fact that it ever does. However, its main difference to the Royal Academy installation is that here El Anatsui and the curators have allowed for a mechanical process which unfurls the hanging structure in slow motion. We see it therefore in motion that is also definitely in real time rather than just imagined time, though the motion is so slow we must still mainly imagine it. The bottom of the sheet is still furled therefore at most times it is seen and bears folds in its rolled state that are quite other than those worked into its relief structure and could not be entirely predictable (of relief structure we can speak more later). It deserves that photograph of the furled sheet to be seen in full:

You feel, walking at this level beneath it, as if its weight might be bearing down on you, quite unlike the light sheen of its imagined motion from a distance. It is clear then that, even since Mullin Vogel’s second edition that El Anatsui’s curatorial and aesthetic process and intentions have succumbed to an evolving practice, for even in the short times since its publication (four years only), El Anatsui’s work is following some new directions of which the book has no coverage, or even predictive power. And in the matter of TSIATSIA the difference here is less than in the effect of the whole wonderful Talbot Rice exhibition, about which I am still reflecting,

One effect of this it make using Mulllin Vogel’s book both exciting and necessary. It is necessary because it seems authoritative in its research technique and interpretative direction but necessary. But it excites for its recognition of the things the book did not know in its first edition because history has superseded it, ensures we know that such supersession has already occurred in the period leading up to this fine exhibition, the catalogue for which (other than in a fine free pamphlet I use here) has not yet been published. I will have then to do a lot of guess work as I proceed, as (to be honest) I have already done above.

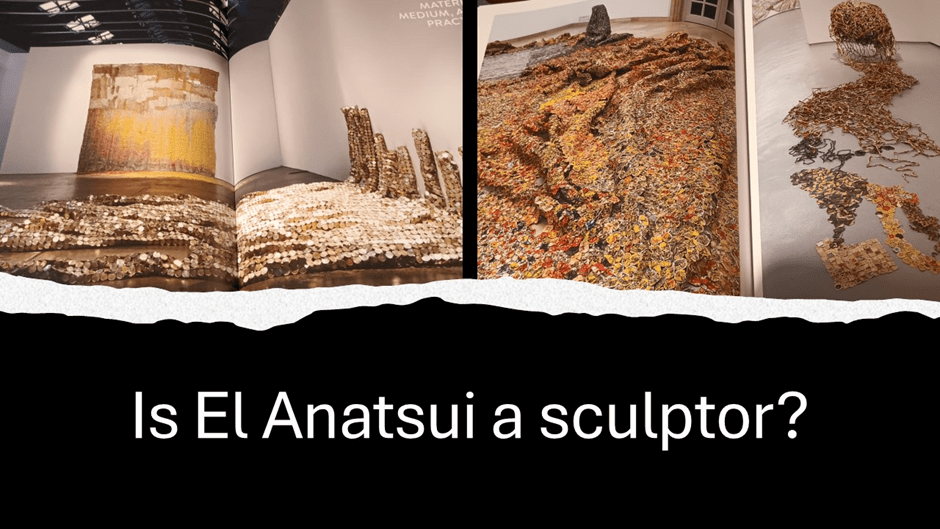

It is worth however showing how much any visitor to this show could gain from Mullin Vogel, even given my last point. From her preface, Mullin Vogel argues that El Anatsui’s practice is changing fro, an ‘art to be read’ with messages about colonialism and the distortions of hierarchical power to an ‘art to be experienced’, whose meanings are emergent and imminent and complex, not like those of simple text.[6] In one sense this could be spoken of as a move from a materialist art to one that claims some kind of ineffable meaning, and a final chapter of her book claiming that a kind of transcendence is achieved also in which ’metaphysical transformation’ is aimed art. By this I take it that Mullin Vogel points to ontological and epistemological in art’s apparent being – never, of course abandoning art’s right to use ‘illusion’, such as those created by shadow) as if it were material. Art here claims a different way of knowing the world it stands in and a different kind of apparent being. Ineffability in El Anatsui’s art is caused by quite simple things. It is an art that denies its viewer simple or singular interpretation of what it is and whose meanings are more a result of cooperative process, in which many agents exert freer choice than is traditional, than a process descending from the authority of the artist alone. The characteristics Mullin Vogel picks out are about an art that is still being negotiated at every level at which it operates – its workshop acts of making by the hands of many persons of many different social classes, skills and aptitudes, and the deconstruction of expected forms. Hence the art refuses prescribed definitions, even definition as either ‘painting’ or ‘sculpture’ though it uses the means of both.

Its curation and its interpretation are also cooperative in ways that refuse the artist’s monologue as a determining factor. The emphasis on non-industrial product and handcrafted hard work that embraces the effect of mistakes made in following plans and other more contingent uses of freedom to alter things ensures this is not art by ‘blueprint’ or prototype.Even changes that occur in a work because a metal shape is draped differently in different settings (as between the Royal Academy and the Old College above) matter here.

Moreover, the art exploits the difference between the materiality of the artwork’s parts and material resources, as seen in close-up, to effects of seeing it at a distance of the hint of representation or meaningful (rather than just ‘significant’) pattern. Most often effects of appearance in later work and certainly in Talbot Rice objects appear to dematerialise the artwork by a process of communally negotiated perception that Mullin Vogel calls ‘uncanny transformation’. There are illusions of the work transcending its material to suggest the means used by another material, even light. For instance, the folds and fall (but especially transverse folds) of cloth, or distortions of light and shade.[7] Traverse folds have been preferred by El Anatsui to decrease the illusion of a hanging curtain or clothing and increase that of relief cartography or sea swells.[8]

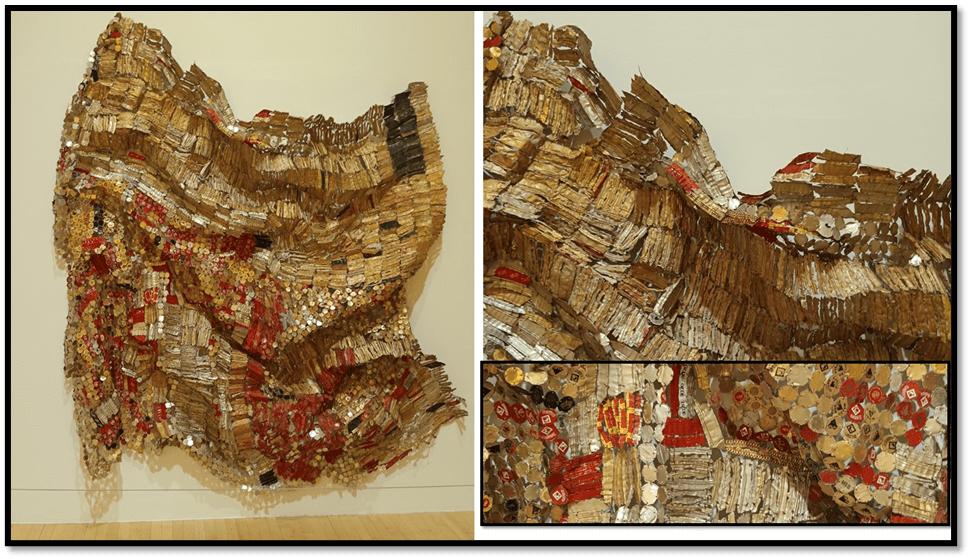

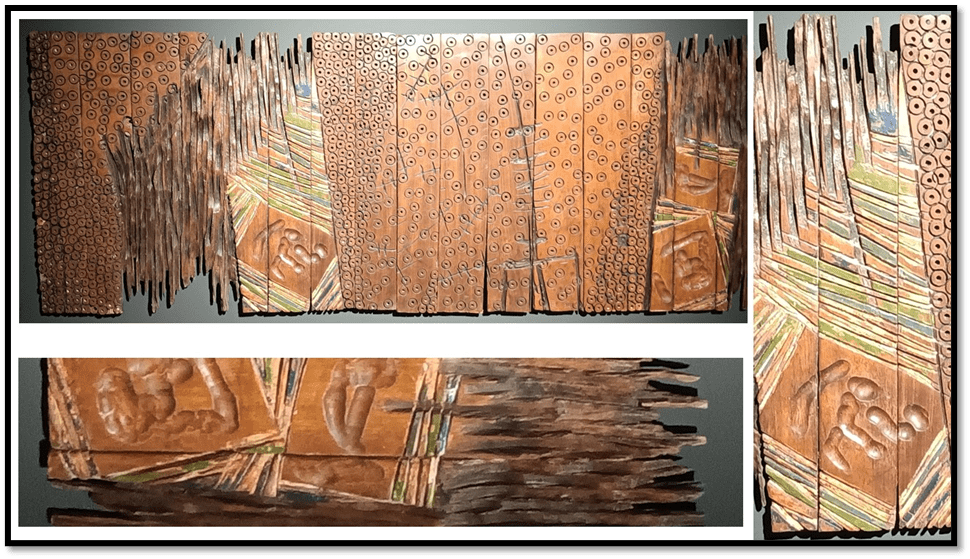

Let’s try that idea out from art at the Rice Talbot show. Below is a collage with details at different levels of focus of a work from 2009 in the Rice Talbot called Bukpa Old Town, that appears on the wall of the Balcony to the White Gallery, the first a visitor enters, although the balcony itself will be some rooms away.

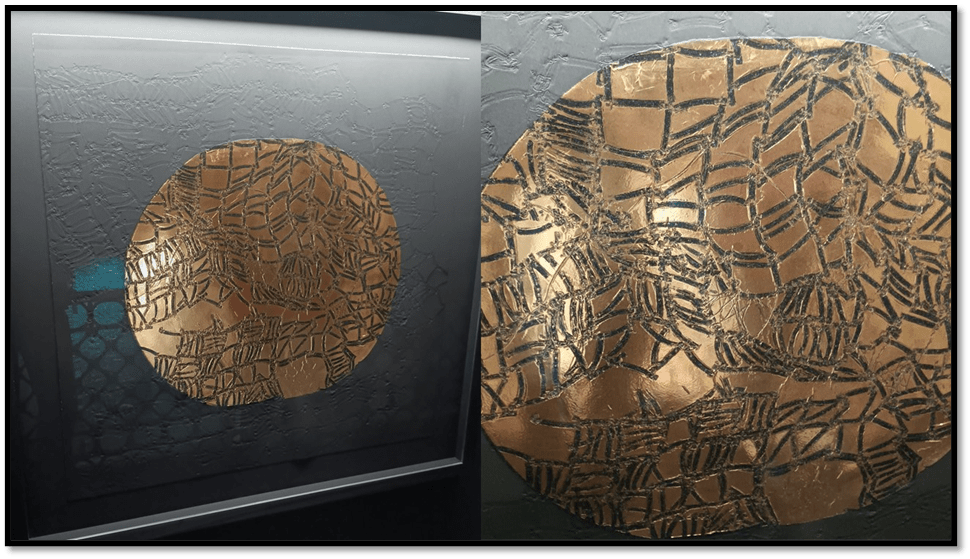

Remember, this is a piece before the noted changes in Mullin Vogel’s book. This piece may then be more tied in its materiality to its intention of being ‘read’ rather than ‘experienced’ more holistically and apprehended numinoulsly. That may, indeed be indicated by the preservation and focusing of the printed text on the aluminium bottle tops. The piece was a companion to another Bukpa New Town, of the same year (but I have not been able to find an image of it). Nevertheless that very comparison suggests a readable message about time and change. What characterises Bukpa Old Town however is that the rich palette (both of colour and bottle-top style sheet binding emphasises areas that are tightly bound and those not so, It is a piece that uses the space between its metallic materialics a great deal, and which causes it to fold in varying levels of rigour. A piece of gaps and absences may well evoke the Old Town and the presence of ‘trade liquor’ bottle tops.

Trade liquour was so called because, referring at first to rum it was part of the trading triangle that included slaves in return for spirits from the West Indies. VBut, of course, it then played its part as with Native Americans, in maintaining the poverty of native Africans in the colonial Gold Coast. Are those gaps reminiscent of the bizarre topography with its dark and shady areas of an old town? That could only be a ‘reading’ open to dispute, but I do sense, given the prominence of the alcohol trading labels, the shadows, danger, drink (sometimes the same thing) of that oppressed geographical outcrop. It fits with El Anatsui’s documented early interest in the fragmentation and ‘brokenness’ (originally devised for early work in ceramics) of African individual and social life consequent on White colonialism and its trade-based excesses.This was Mullin Vogel says a theme featured in the artist’s:

lifelong oeuvre: because breaking is usually unintentional and unpredictable and the fragments are inherently unstable , these ceramics – like the bottle-top hangings – can be read as a frozen moment in an event that remains incomplete.[9]

Mullin Vogel has a summary of this theme later in her book which treat rupture, breakdown, corrosion and decay *and sometimes destruction by fire) as both tragic and hopeful elements of the warp and weft of art.[10] Yet even thus early a bottle-top sheet can whether hung or collapsed as a standing sculpture (dependent on curatorial readings arrived at collaboratively – point to the holes and absences in it as part of both its process of facture and its potential meanings, in relation to the fragmentation and ‘breakages’ in lives (social and individual) it may record. And, as part of this (look again at the collage) shadows falling on the hanging and creating presences behind, below and to the side of it become part of its aesthetic, and even facture at the level at which it is installed in one of the many venues at which, like any migrant, it is mobile.

I think we see in The Talbot Rice collection (here even in an early work) that sometimes the design utilizes the immaterial – the fall of light on a work that contains gaps and omissions or the depth of a fold, or trough and swell of a surface. These enter into the meaning of a work. What Mullin Vogel asks us to look for in the later work in particular is the idea of an immanence of meaning that utilities its silence as a work (sometimes represented by gaps between text on coloured materials) as does Anish Kapoor, whom El Anatsui admires,in order to create a sense of a monumentality that instead of bolstering it, deconstructs the authority it is based upon. El Anatsui, she says, He aims to use the base nature of his materials to aim at a suggested state that is ‘exalted’ as in religious ritual (without being religious).

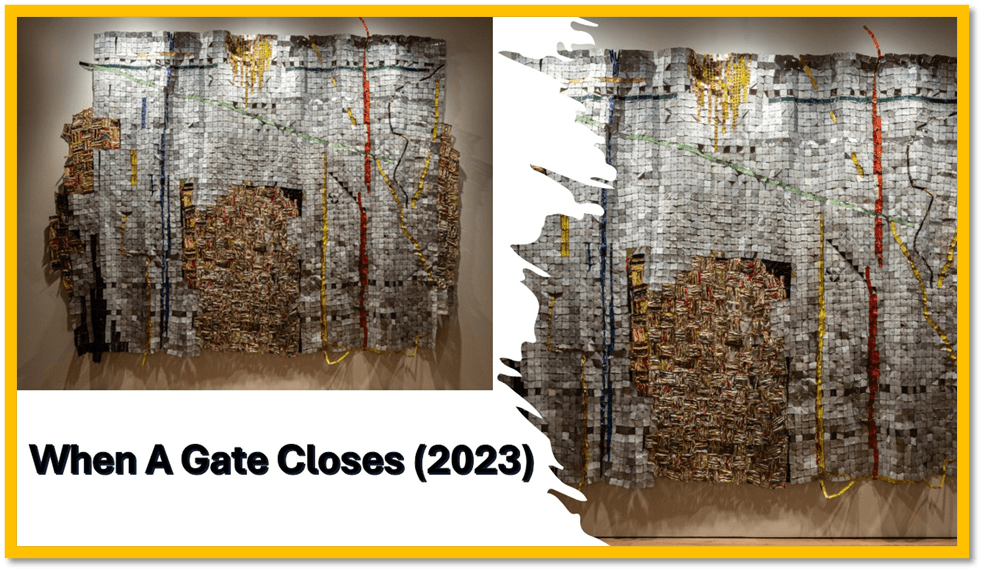

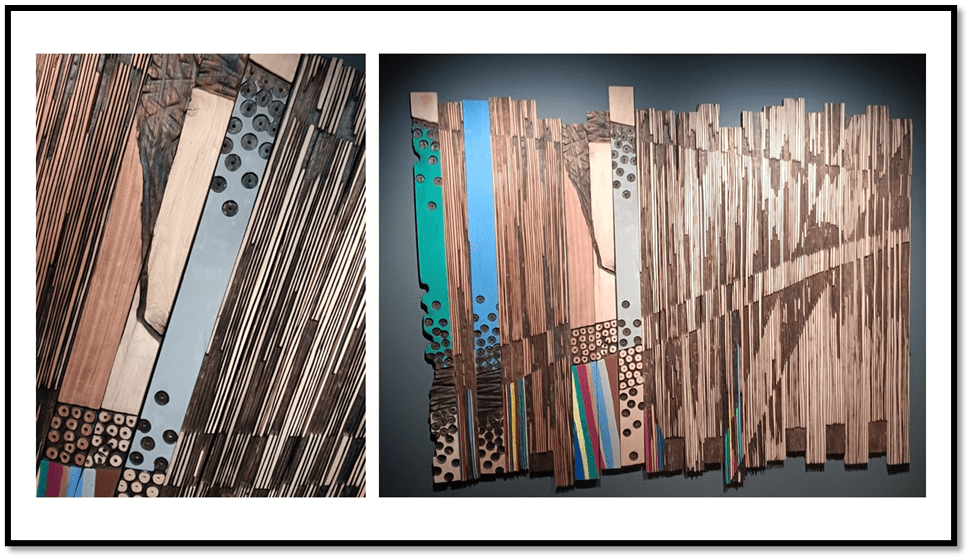

This seems important to El Anatsui as a way of using the bottle-tops from the alcohol ‘trade’ (once implicated in real slavery and perhaps in metaphor still implicated for those in poverty), for instance, which have brought many low (perhaps unintentionally) but certainly to the effect of exalting the colonial white few in contrast to the lowering of the many, people in the mass, debased by systems always intended to advantage a few, as we have seen.[11] But let is test Mullin Vogel’s sense of change in the art against a later hanging, she could not have included because it was completed only in 2023, When A Gate Closes. This, to me, clearly metaphysical was situated near the end of the exhibition (and is perhaps valedictory) in the ground floor of the Gardner Gallery (I will supply maps of the museum layout later). Gaze at it with me in the collage below:

This work uses tighter binding (although the materials – aluminium and copper wire are exactly those of Bukhpa Old Town – and, as Mullin Vogel suggests he might, employs illusion more – of depth or sheen, or reflectiveness (it uses the back of the bottle tops on a lo of its visible surface, through interrupted by icons of rivers or straight roads in full colour and its seams of connectivity). But it also uses colour palette effects based on the stitching of its sections to create more three dimensionality – in real space in its folds and seams, in imagined space in its depth effects, including the ochre are we might treat as a door closed in out face. The aim is to celebrate, I would say the space of travel that migrancy involves and the shifts in interior responses as well as in the seen. The sheen of the metal surfaces suggest a mirror in which we might see a ‘fractured’ (and certainly a factured) image of ourselves or many such in its defined particles. But note too the effects of shadow, on the surface of the taut sheet registering real differences of relief height between its parts but mainly, in this one on its margins.

On the lower margins, these shadows help fringe the art with something definitively uncanny, a sense of something hiding behind a curtain. This is one of the few that uses folds as they are used in Western Baroque painting to suggested the hang of cloth, for the illusion of cloth returns here from El Anatsui’s past work. Mullin Vogel had said in 2020 that the artist was:

particularly unhappy to see a sheet with vertical folds falling earthbound all the way to the bottom, evidently because their curtainlike ripples connect them to prosaic domestic things, like drapes and laundry, …[12]

Yet here, though the vertical folds are not consistently ‘all the way to the bottom’, they are suggested. This suggests that, El Anatsui is inclined now to see more of the use of mystery associated to drapes in Western art, either in Baroque forms or in Henry Moore. The shadows contribute to the silent immanence of the piece which both celebrates and mourns endings as we all must, for without them there are no beginnings. The title When A Door Closes seems to invite thoughts of closure and disclosure, the closed and the open in art, that is near to what I think might be meant by the metaphysical transformations seen in the art.

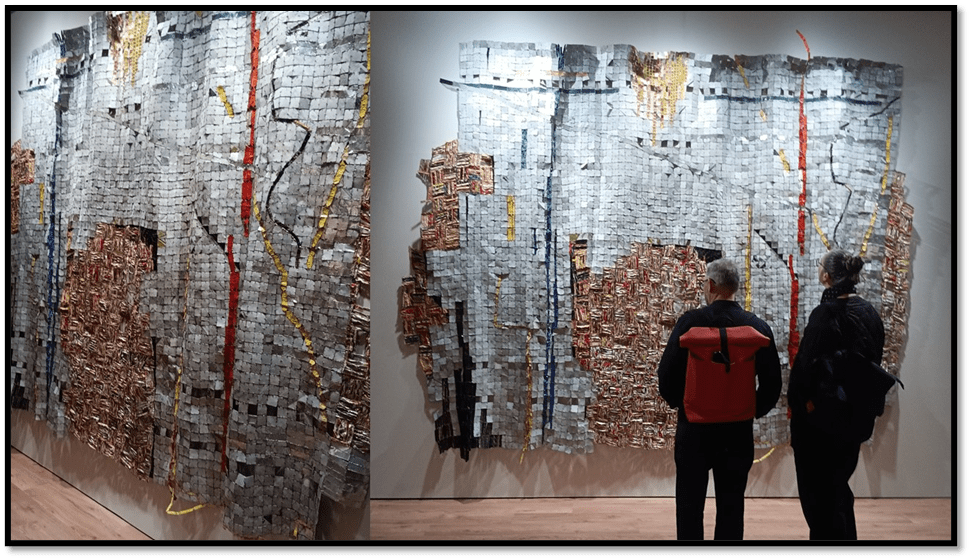

Of course, all this depends on so many actors. These sculptures are only such once installed and, as we have seen this is a collaborative process. But even installation is not an end. For viewers see things differently. At first we do not need think of subjective response here yet, for in my photograph above we can see people looking at this piece in the Rice Talbot. They chose that space and stayed there and moved on, but is this how we see sculpture. Granted we cannot walk around wall sculpture, but we can vary our angle and distance of looking, oft then chiming with differences of seeing. Looking and interpreting art ideally remains thus cooperative despite the infantile search for evidenced readings that still predominates in art history. I like to look from queer angles: and many of them.

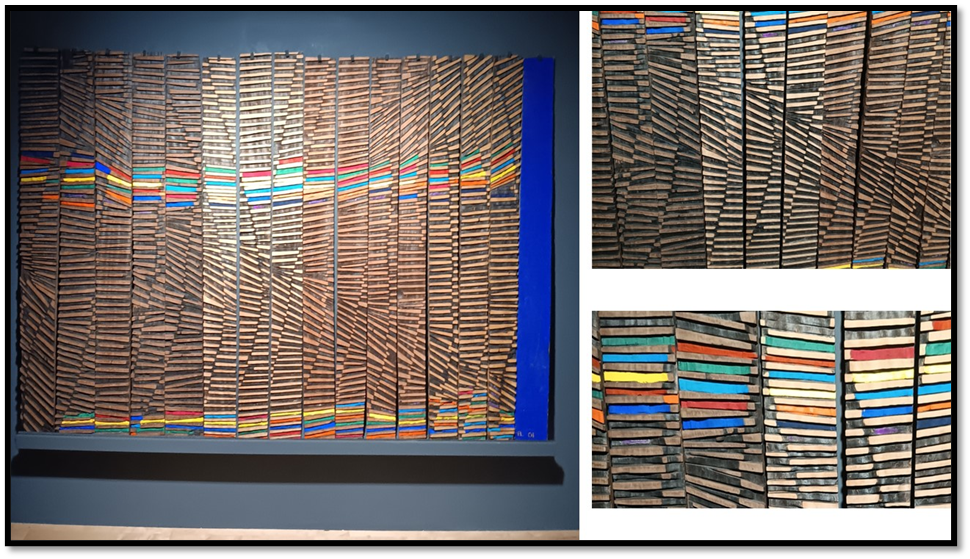

But enough of this prologising. My intention is to take you through the Talbot Rice exhibition with selected stopping points. But before that let’s consider some very obvious (unlike those above) advantages of having read Mullin Vogel. First, she reminds us that El Anatsui was the first, or so it seems, person to choose bottle-tops as a primary medium (though other media are in this show – some startling different as in the Gallery Balcony as we shall see) and there are things it might help us to know about how we might craft with them following his practice. However, I do not intend to summarise these, just point you to the existence of the gazetteers in the book for that purpose. There is a wonderful chapter on the methodologies of used in the materials, including his start with metal-can lids sewn together with metal wire, but leading to a taxonomy (called a palette of the kinds of different binding used with the bottle tops. As with all taxonomies, they have limitations in art if they are used only to categorise rather than help see how they ‘connect’, for connection is El Anatsui’s theme. But you can use them intelligently. Here is a sample of the ‘Bottle-Top Palette’, showing the gazetteer portions.[13] I have added Talbot Rice pieces to show the need for more than classification to the bottom of my collage.

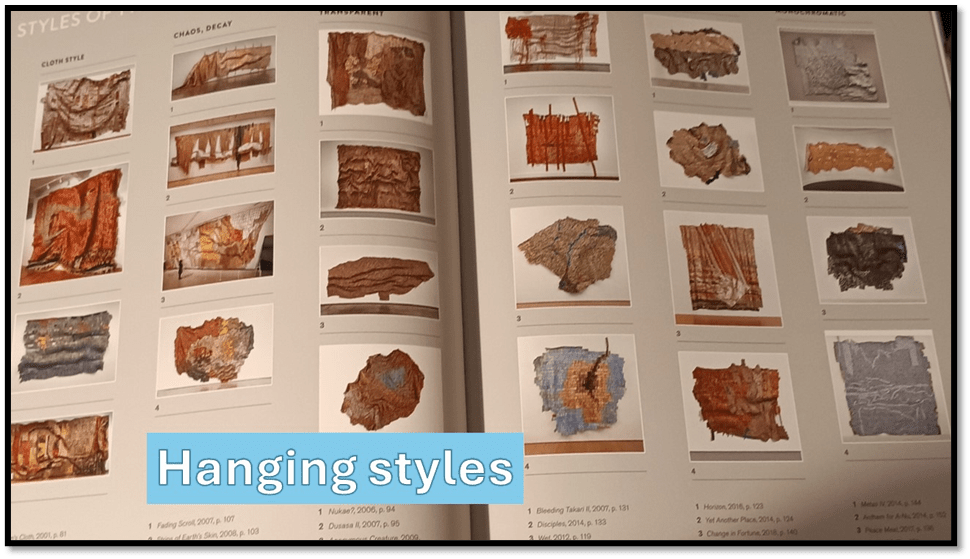

There is another taxonomic section – this time of what Mullin Vogel sees as the differing STYLES of bottle-top completed artworks, but it needs even more of the same caution to use it well.[14] However Mullin Vogel’s text falls into none of the traps she might be setting herself here. For instance some of his techniques, such as mosaic technique are meant to recall the Roman practice with tesserae, as part of their meaning, where the form of connection is entirely different.[15]

But let’s look at some of the means of binding and connecting in more detail, if without further comment:

Another theme hangs on this issue of style however before we begin a tour of the Talbot Rice. As I have suggested El Anatsui gives curators considerable freedom in the means they drape or present his ‘hangings’ as sculpture, although his voice remains in dialectical play with these curators. As Mullin Vogel says: “Every time the metal sheets are moved or reinstalled, they must be acted upon and must change. They are not visible as works of art unless’ that happens.[16] Sometimes curators have hung the pieces so you can see the fall of them on each side, or collapsed them into floor sculptures or hung them with a refined lighting of their own devising, perhaps even draped them across a floor near-horizontally rather than vertically.

These are all features of the art’s ‘form’ that Mullin Vogel calls ‘NON-FIXED, NOMADIC’.[17] The art is hence replicating the features of adaptation required of all nomads. Yet even he admits that it took him time to discover that a thing is still sculpture if you can’t walk all around it. Nevertheless, as I looked at photographs of other exhibitions in Mullin-Vogel I have to admit I rather like the drama of these earlier exhibitions, for the drama at Talbot-Rice is perceptual and based on the imaginatively kinetic rather than the kinetic in obvious space and time, although I have already shown that we need to vary our looking-stances to see El Anatsui’s work in all its splendour. However, look at the exhibitions shown in my collage (from the book). As I looked at these examples of other exhibitions, after I had seen the exhibition in Edinburgh, my first response was of a little retrospective disappointment that this current exhibition had such a conservative use of three-dimensional spacing and mainly examples of art hung on walls. However, latterly, I will explore before my next examples, I think my first response was more naïve – in believing that sculpture that utilized and filled more of the three dimensions of space, rather than largely two, was more appealing. For to think that is literally to think entirely superficially.

Left: ‘Five Decades Exhibition’ at Carriageworks, Sydney 2016 (bid: 156f.) & Right: ‘Tiled Flower’ 2012 at Haus der Kunst, Munich 2019 (L) & ‘Uwa’ 2012 at Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University exhibition undated in source (ibid: 178f.)

There is a childlike fascination in art that crowds three dimensional space. How conservative for instance on first glance appear scenes from the Georgian Gallery floor (seen from its balcony, on the left of the collage below, in comparison with the floor spreading standing sculpture top right and the free standing assemblage of sculptures bottom right of my next collage.

Left: 2 views Looking down from Georgian Gallery Balcony (my photographs) & Right: top; ‘Waste Paper Bags (2003) both at Brooklyn Museum exhibition 2012 (ibid: 175) & bottom: Logolili Logarythm (2019) at Haus der Kunst, Munich 2019 (ibid: 173).

There is something satisfying about an artist (or even the artist & curators) having commandeered my space and thereby guiding me through it, but, though this increases the sense of something exciting and new ready to fulfill the urge to use all the space around me it reduces certain freedoms from the viewer – to choose their own point of views on the artwork (and choose to vary, in whatever pace they also choose, their point of view to other loci).In fact, I became grateful for an apparently conservative use of space (except in non-changeable spaces, like the ‘Round Room’ of course, which is part of the basic architecture of the gallery. Empty space is really not empty but free space. It allows the viewer to take up perspectival, and indeed conceptual and emotional, positions in relation to the art, or so I believe anyway.

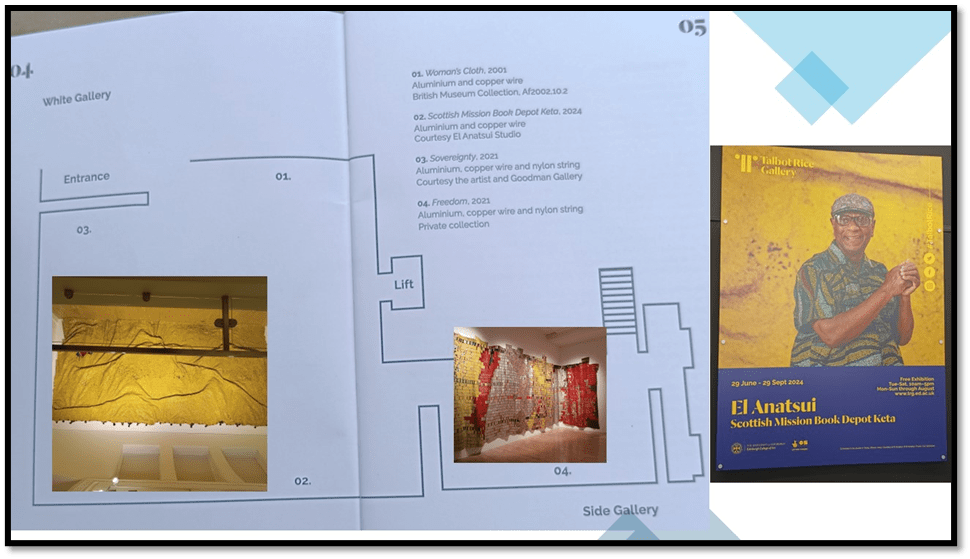

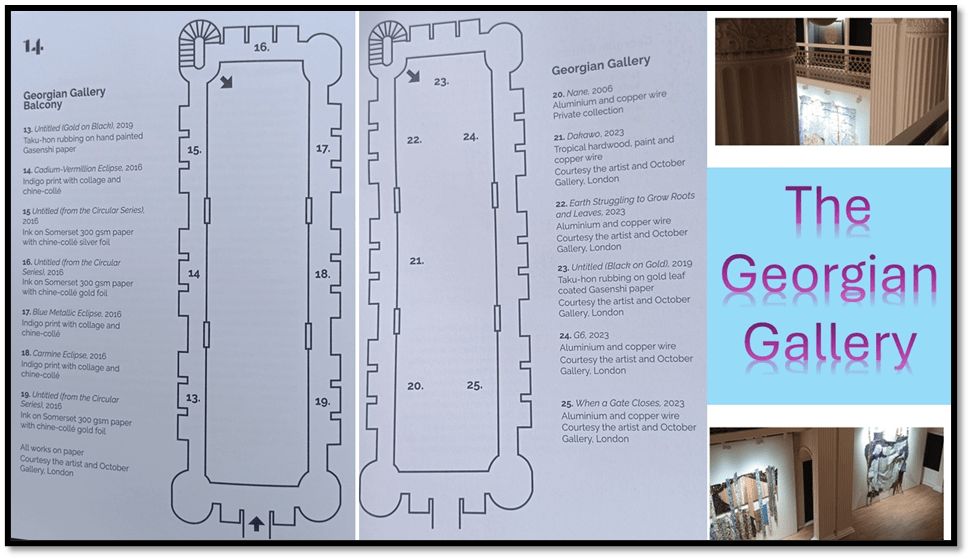

But it is time for a tour, stopping at selected items. I use the free catalogue’s maps to guide this in a collage. Let’s start where all visitors start – at the White Room, and move on from there:

There are three works of art in here but it is difficult not to be overwhelmed by the star of the show that immediately faces you and gives its title to the exhibition – an autobiographically determined title: Scottish Mission Book Depot (2024).

A collage creating an impression of the work Scottish Mission Book Depot (2024)

Referring to a time when Anatsui (before he adopted the nom de plume, El), this work might be said to also reference, and is by El Anatsui currently, his childhood in a expanse of space that looks unvaried but is not, perhaps a time when the richness of perceptual life can be forgotten. The bright coloured marks on the right are , El Anatsui says, to allow us to capture the excitement of young Anatsui being gifted crayons by the Scottish Presbyterian Mission and thus beginning his yearning to create art and make his marks on its surfaces. But it also insists that the life was not so plain nor as un-enriched as it might seem though framed by the poor resources that colonialism allowed to the colonies through supposedly charitable mission houses. For Anatsui the connection to Scotland begins here and the Presbyterian minister, his uncle, who adopted him. In creating this art work for Scotland, El Anatsui wants. to reference all this.

This work might look like a drape curtain masking something, just as it also conveys a huge, animal-unfriendly and dry landscape, but its detail and its features from a distance all create a sense of the uncanny. Folds in a curtain rarely transverse across the surface on which the formed and these look more like rifts and valleys, or engulfing sand dunes, or a sea that is unnaturally dry in its captured appearance of odd swells and troughs in calm conditions. To look in detail allows you to see how shadow is employed to make these rifts rather more uncanny and forbidding, such that they can appear as cracks and fissures of a whole connected thing about to fragment. The bottle tops themselves are laid like tesserae, but vary in colour (some by using the verso of the bottle cap, others by effects of light on the folds and gaps), but sometimes because in the tessellated an alien colour is trapped and isolated. Even the tesserae (connected of course) seem to want to use the tension of a fold to pull apart (see the top right detail in the collage below).

In the details above, you may also see how deep and dark the shadowing is within these holes – as if the sheet had gaps, absences and holes, Sometimes, as in the next details there are clusters of multi-colour (not as dramatic as the ones representing a child’s vivid crayon marks) but effective, as if alternative forms of queer connection were happening in the whole and exerting pressure on it to change. These clusters (and even some bottle-tops preserve the serrations of a beer bottle, as if the fact that edges spaces are sometimes a problem in connectivity was an idea forced upon us, if we look closely. But notice too the shadows at the edges of this piece which emphasise the gaps in the connection of its base materials and show like the reflection of lace. It is a very delicate aesthetic effect.

Of course, the other works in the room also interest. The dramatic Woman’s Cloth – below – (2001), a companion to Men’s Cloth in the British Museum has much in that comparison to say about sex / gender in African psychosocial life, but I don’t intend to pursue that having never seen the comparator, It is a most beautiful work that employs not only folds but fold-overs that suggest something both concealed but perhaps also the product of fracture or collapse caused externally, by men perhaps, and, at another remove by trade alcohol.

A newer work, Sovereignty (2021) clearly does refer to national identity. In my college I include the whol;e and two details. Recalling a flag at some level, this piece is also a map that attempts to show the falsity of borders and edges, just as it implies the violence that guards them. There is something like a flow of red blood over dried blood in the whole that is absolutely fearsome. Borders are always incomplete, sovereignty incomplete. There seems seams of otherness that actually attempt to give life to the idea but, on the whole this work is dark and aspires to unusual flatness, for a work by El Anatsui. In his childhood home where sovereignty was pursued mainly by competing European colonials, this piece seems to me like a car on the soul of Africa.

We move on to the Side Gallery. Here one piece increases its dimensionality by being hung around a corner o the small gallery. This work Freedom returns us, the free catalogue asserts to the critique of the colonial alcohol trade (the name ;trade spirits’ was used) that has been so implicated in the deliberate and active under-developing of Africa by colonists eager to take the rich resources available whilst seeming to favour the cultivation of the African spirit. The names on the bottle-tops are often of liquors implicated in the trade.

Freedom (2021)

This work is spirited in every sense, its rich palette (of colour and of bottle binding variations) and complex margins, and external (at margins of the whole piece) and internal shadowing effects, it unusually allows identification of itself with a curtain with ‘natural’ vertical folds. To me this emphasised the sense of duplivity and cover it also dramatically signifies, a freedom forever compromised bt what other people call ‘natural’ and ‘realistic’ but which to the person on which such freedom is imposed (to drink alcohol for instance) has the feeling of a cut across skin and a staining of blood.

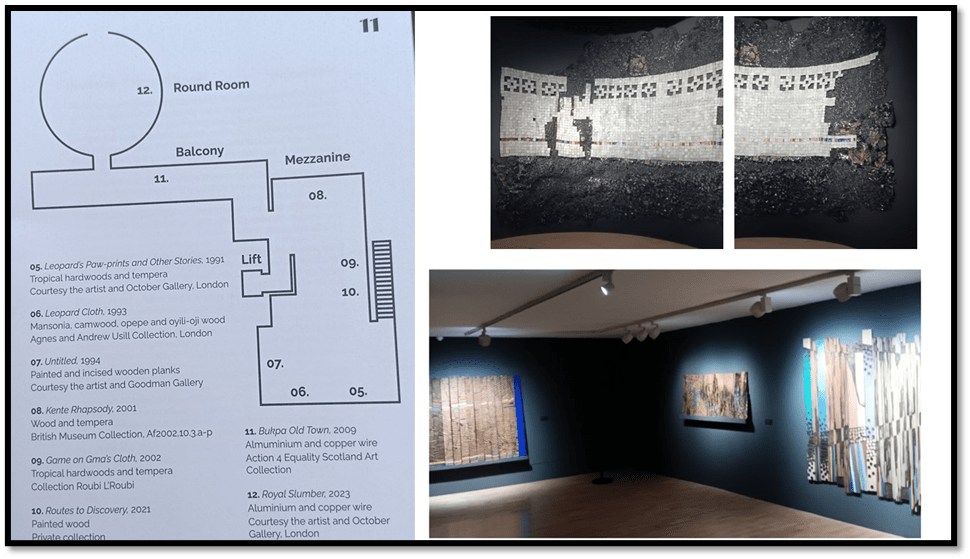

We take the stairs now to a room on the next floor, the gallery calls the mezzanine because it split the original room to create two storeys at the side of the White Gallery. The Mezzanine Gallery is given over to an earlier phase in El Anatsui’s work, which strained towards indigenous forms, but not in any straightforward way (see the room on the bottom right of my collage, the top right showing the Round Room) .

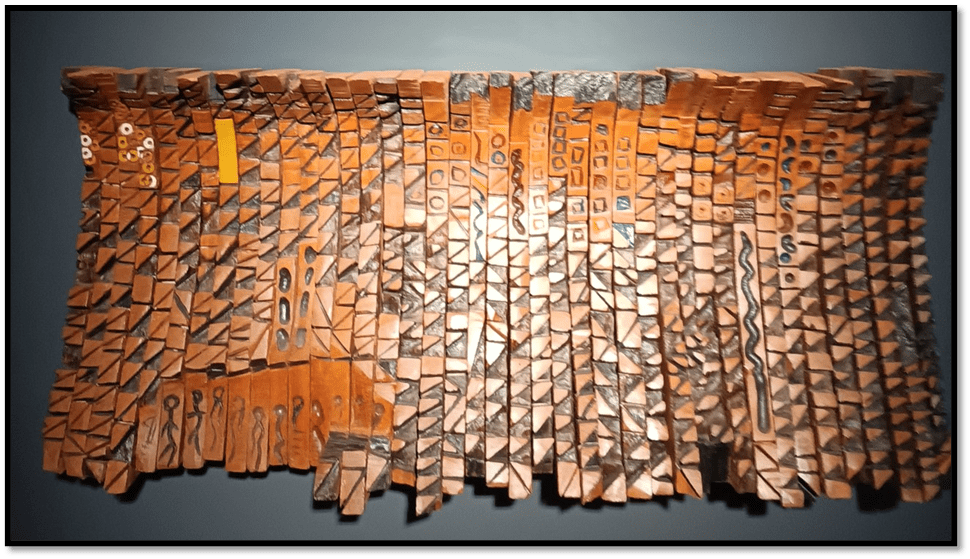

The indigenous art is at its most obvious in the art in cut and burned wood. To a certain extent the desire to ‘indigenize’ was according to Mullin Vogel a reaction against the dominance of western form even in post-colonial African art school and related to the suppression of information in education systems of indigenous traditions. The aim was though not so much as to revert to ‘traditional’ forms as to incorporate them into art that always made claims to global modernity. The belief that there were no ‘neutral’ cultures nuanced the approach to this art and ensured that research into traditional form could be incorporated into freer modern forms, including subjective ones. For instance, in speaking of his art in the 1970s El Anatsui spoke of using adinkra symbols for 4 – 5 years, burning or carving them them onto wood surface,s but then varied them, moving towards creating ‘my own signs after these’. [18] Of a later work, Leopard’s Paw-prints, and Other Stories (1991 – below), the Edinburgh catalogue references ‘Adinkra symbols and his own created signs’.

Only at first do these patterns seem traditional in design. They in fact depend on ruptures in traditional design, gaps on the surface in which new anthropomorphic signs of a connected humanity are inscribed. For my purposes I loved the way these relief structures – varying method between those which built up and those which worked by destructive omission (the burnt margins of some parts to create complex motifs of connection and disconnection. Having little more to say than this, I will just show you the collages I made of specific work and details in them without specific discussion.

The entirety of the overall theme, even in radically different pattern effects is to compare straight, cut And burned edges, embedded symbols that are stranded between past and present and confuse boundaries and margins of the work internally and externally. These works are beautiful but I need more learning to understand them.

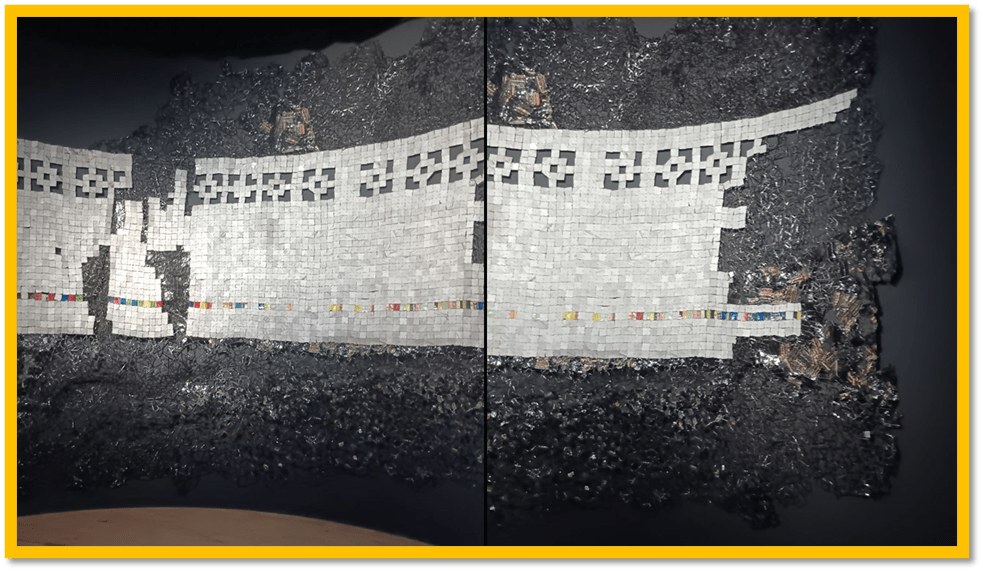

At this point, we cross over the balcony revealing the White Room again beneath us and into the very Gothic uncanny of the darkened Round Room, displaying on the curved wall a beautiful work in aluminium bottle tops and tags linked by copper ware in mosaic form. It is called Royal Slumber (2023). In this room quiet is encouraged so that the sleep of a putative monarch is not disturbed, even if reverentially viewed. The catalogue cites words like this with out irony, but the work itself requires seeing from all kinds of angles including ones impertinent to monarchy. Here is an impression of the whole:

However, I sense irony here. Th white aluminium plates bear printed paper squares cut from University printed paper. What I feel is that El Anatsui is putting authority, especially those authorities that ask those beneath them hierarchically not to disturb their rest under pressure, creating the illusions they need whilst simultaneously undermining them by exposing them to a critical view, one that can see their fragmentation, desire to hide – beneath symbols and signs, and walls, that are nevertheless crumbling, even burnt, as they look, after regenerative fire. It is a transcendent work but it is not so at the cost of analysis, for transcendence is too oft acted out by the privileged as a mask, to stop people seeing their own potential power. It is heady stuff, this art.

You blink in the light of the Georgian Gallery as yo enter its library. Were I to go again, I would spend much more time on the balcony for these new works are stunningly original and yet seem to evoke ancient models.

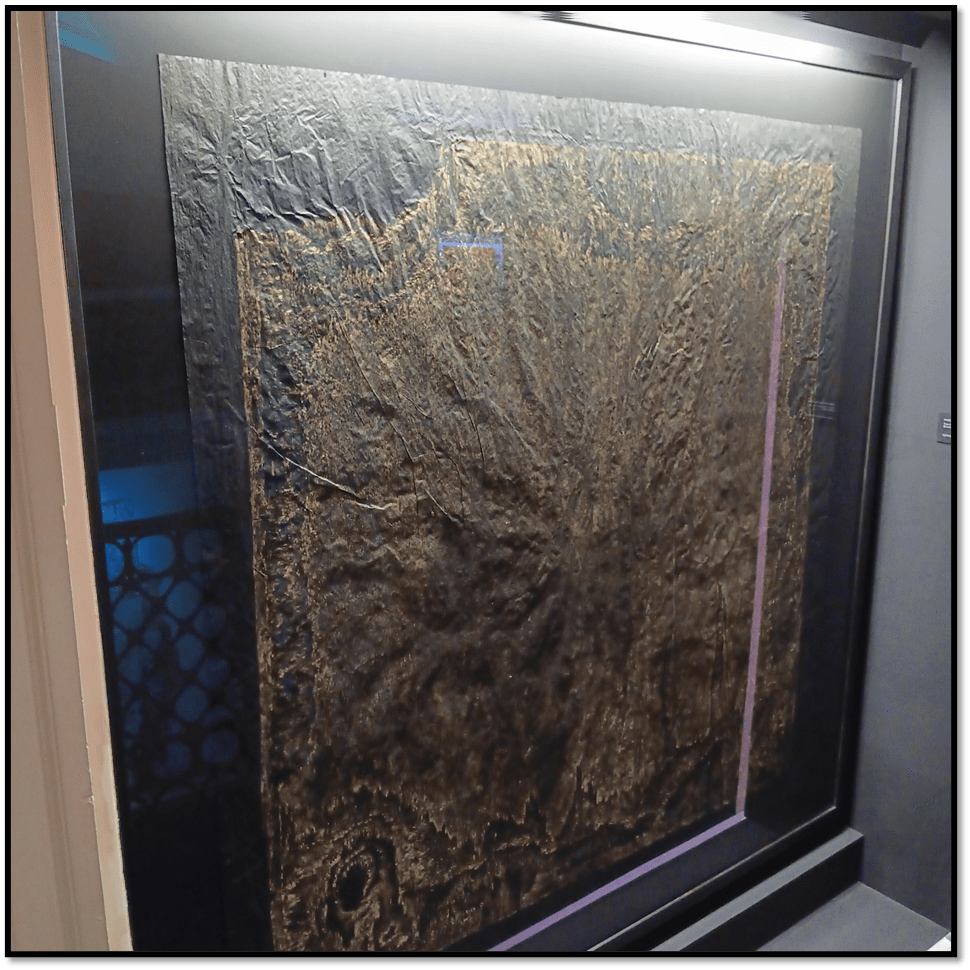

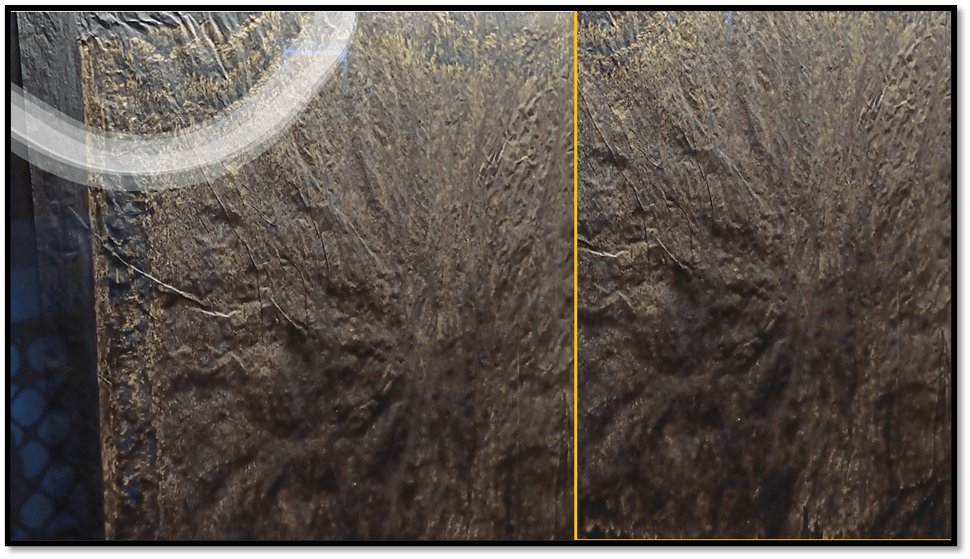

I notice that the Gallery staff photograph these works from a distance, from the balcony distant from them. As I walked around, another visitor shared with me her view that these works were unphotographable. As I looked at my photographs I saw one reason for this was framing them behind glass, an unusual feature in El Anatsui’s art, and which ensured that the lit gallery was reflected back from the perceptual surface offered to visitors. Here is my picture Untitled (Gold on Black) [2019].

The rubbed paper creates its own cartographic relief, but you strain to differentiate what is in the picture and reflected on the glass – for instance the ornate iron tracery of the Gallery Balcony shows quite clearly. I cannot believe that the artist and curators did not themselves notice this perceptual confusion. The point then remains – is it, like the shadows cast by lighting on and from relief sculptures also part of the art. It is this I need to re-examine. After all, these works were collaborative with Factum Arte, famous for their interest in the illusion of originality in anachronistic factures (see my blog on their work in the Bishop Auckland Spanish Gallery here).So for now my offering of my collages with a special plea for the beauty of the eclipses. Again I need more – perhaps the formal published catalogue, but I did ‘experience’ these works for certain without knowing if I could ‘read’ them.

Moving to the Gallery floor down a spiral staircase is an experience in itself but the work down there is extremely beautiful. There is much stress in the catalogue in the likeness of these works to conceptual cartography and to themes of environmental survival, a strand in all the new art. At this point, exhausted, I needed just to look.

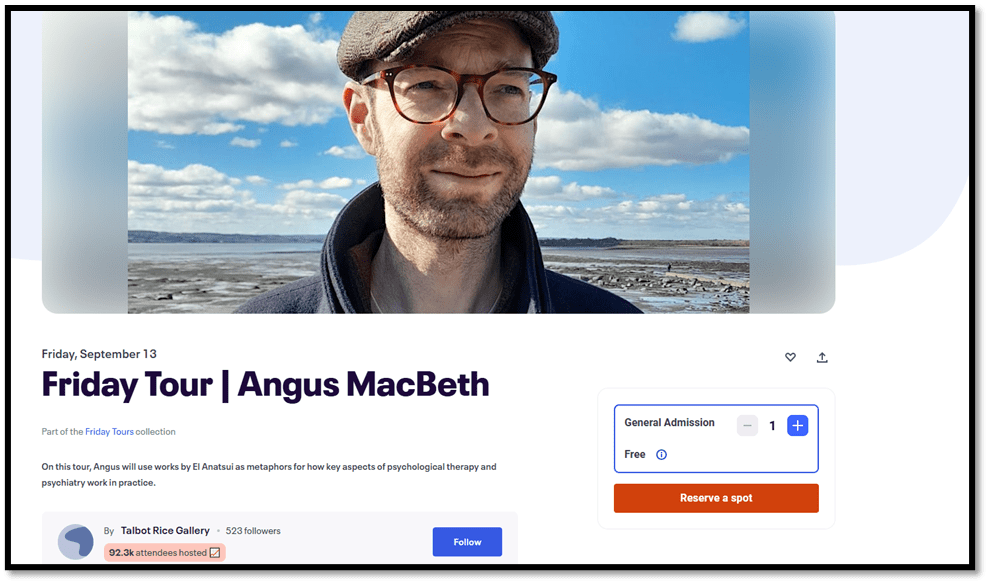

How we see art matters. Earlier in this piece, I referenced When A Gate Closes. Interestingly enough a clinical therapist is going to talk about that work as a metaphor for psychotherapeutic purposes. I can’t go. I wish I could. Here anyway is the event description:

Angus MacBeth is a Senior Lecturer in Clinical Psychology and Clinical Psychologist who researches intergenerational mental health. On this tour, Angus will use works by El Anatsui as metaphors for how key aspects of psychological therapy and psychiatry work in practice, whilst also illustrating how his research applies to global mental health in countries including Malawi. Looking at When a Gate Closes, Angus will talk about how the impact of trauma can be passed on through both biological and social mechanisms. Anatsui’s prints will then offer an opportunity to consider Attachment Theory and the importance of representation in therapy –focusing on the stories we tell about mental health. Closing with Scottish Book Mission Depot Keta, seeing this huge work as a complex tapestry, he will explore how in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy important insights into mental health arise from the accumulation of details, offering a window onto the value of learning how to change the way you think and behave in the world.

Art ought to serve multiple purposes. Why not contact Eventbrite and secure yourself a free ticket. Meanwhile I need to go again I think. El Anatsui has grabbed my heart. His is an art that cannot be ignored.

With love

Steve xxxxxxxx

[1] See: https://livesteven.com/2024/08/25/the-second-of-2-days-at-the-edinburgh-festival-a-blog-covering-events-on-23rd-august-2024/

[2] Susan Mullin Vogel (2020: 154f – spread) El Anatsui: Art and Life Munich, London, New York, Prestel Verlag

[3] Ibid: 15

[4] Ibid: 69, 141, 161

[5] Ibid: 195

[6] Ibid: 6

[7] see ibid: 182 – 185.

[8] Ibid: 24f., for Anatsui’s dislike of vertical folds see ibid: 185

[9] Ibid: 46

[10] Ibid: 162f.

[11] See ibid: 198 – 201

[12] Ibid: 185

[13] Ibid: 75 – 77.

[14] See ibid: 114f (spread)

[15] Ibid: 86

[16] Ibid: 19

[17] Ibid: 159f.

[18] Ibid: 33 – 35