In yesterday’s blog I wrote, referring to Ralf Webb’s fine book (Strange Relations: Masculinity, Sexuality and Art in Mid-Century America, [2024] London, Hodder & Stoughton) and referring to his section on Baldwin

Of James Baldwin I could not get enough. I will read him again, when I have finished Colm Tóibín’s new book on him at least, but I am reading that NOW. Here books by Baldwin I read, at the time when they were culturally ‘hot’ like The Fire Next Time , I must read again for its contribution to the analysis of intersectionality is clearly seminal, arriving at a time before people even thought of intersectionality or queer theory.

This seems now weirdly theoretical and cold, and that is not the fault of Ralf Webb, but I felt it to be so much more the case after reading Colm Tóibín’ On Baldwin, which is a book about the passion for writing and the reason why writers actually write, embracing its pains like isolation, false returns and their necessary painful revision into something like a witness to one’s experience. Tóibín’s book is as much as about himself, and other deeply committed writers, as Baldwin. Those writers are not all writing always in the form of novels,and although the book steers through the analogies of Tóibín’s experience of growing up queer in Catholic Ireland involving complex placing of the queer man inside a loved community that is as liable to turn against him as his known enemies, as did some witnesses to Black oppression to Baldwin, even followers of, though not the man himself, Martin Luther King.

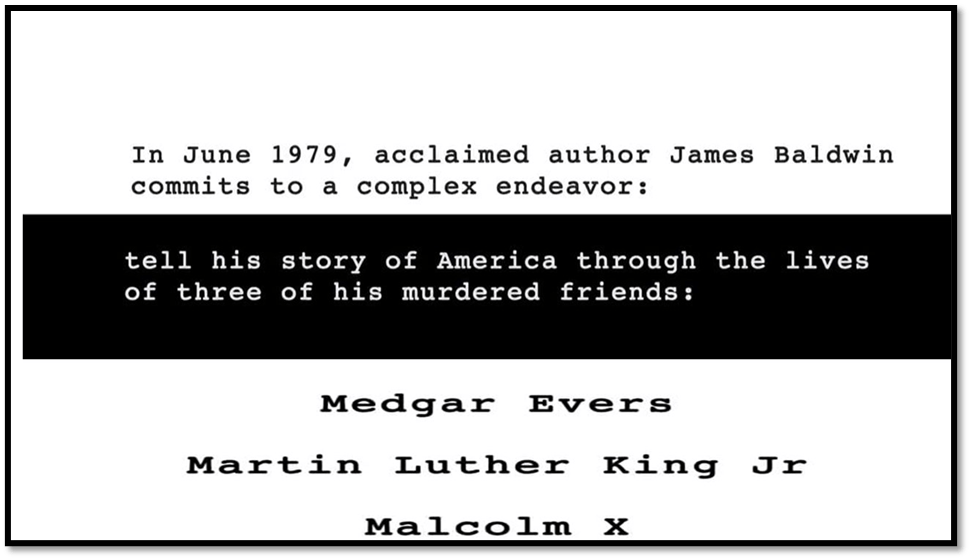

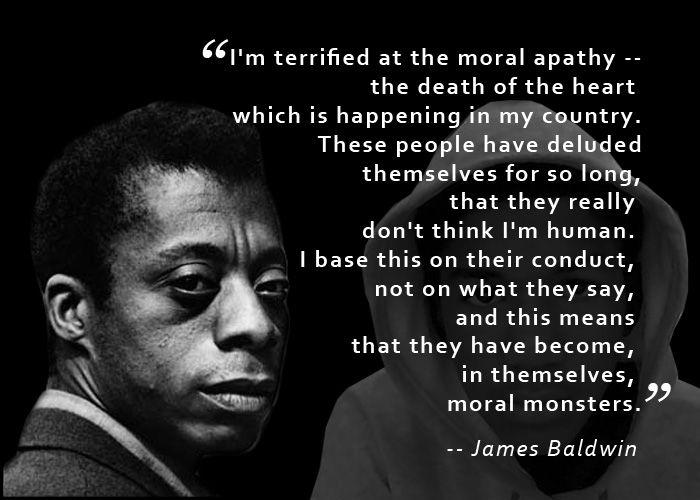

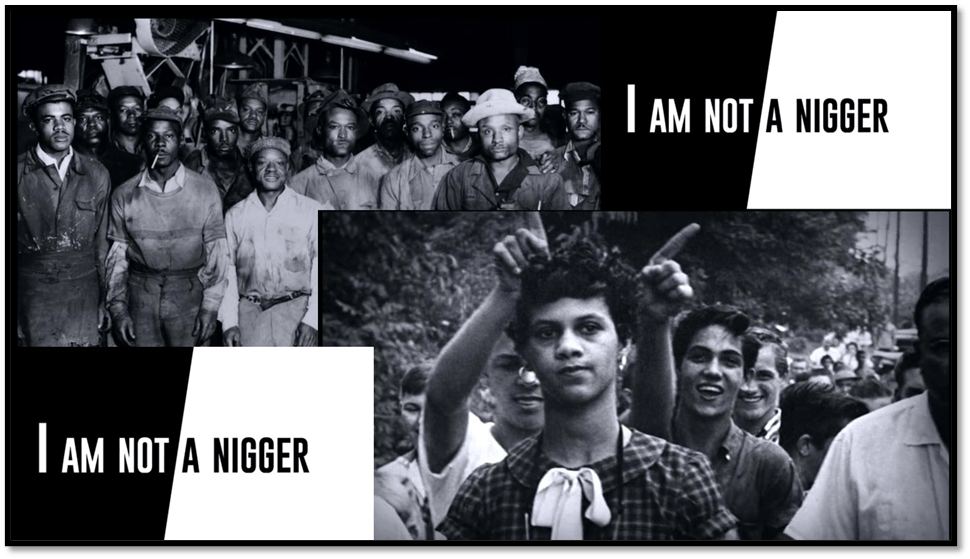

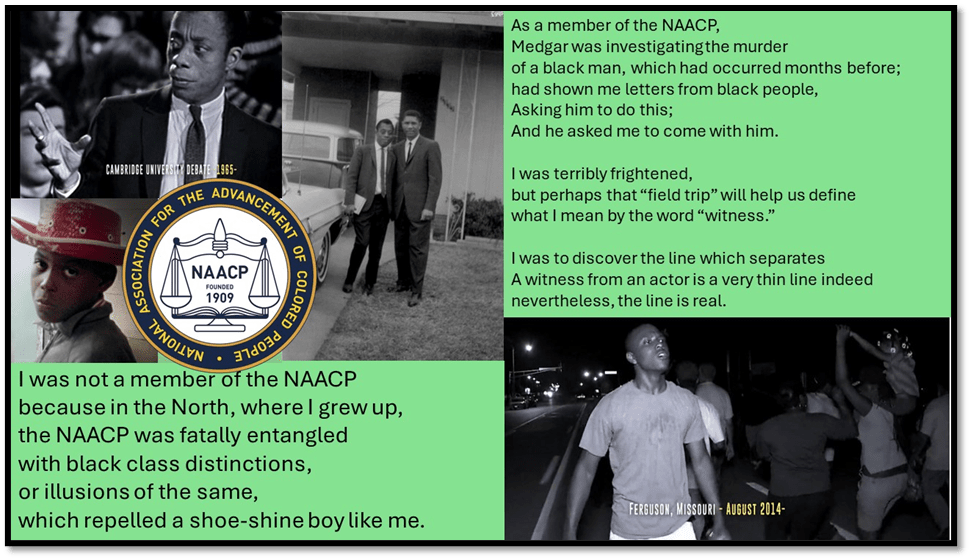

All of this needs separate reflective discussion in another blog. But the book did raise an issue for me. I have been waiting to watch, for to my shame I have not seen it, Raoul Peck’s acclaimed film I Am Not Your Negro, based on an unfinished 30-page manuscript of Baldwin’s found at his death, and entitled Notes Towards Remember This House. Remember This House got no further than these notes and required revision by Peck, and editing by Alexandra Strauss, both of whom provide fascinating accounts of their process and how Baldwin’s practice as a writer justified it in the published text (with stills from the film) of the screenplay [1]. It’s purpose is summarised in captions from the film below:

Yet for queer readers, perhaps mainly entitled White queer readers, there has always been, since the film emerged, a problem in its reputation, and I knew of this and had delayed watching the film for that reason. The reputation can be best summed up in this ending of a review of the film in The Atlantic. It is an idea however that was even repeated in the publicity prior to the film’s recent showing on TV:

This ingenious movie allows viewers to fully appreciate Baldwin’s unmatched eloquence and form a portrait of the artist through his own words, even if the film largely (and somewhat inexplicably) omits a crucial aspect of his work and life: his sexuality. [2]

A lot is assumed in the adverbs ‘largely (and somewhat inexplicably)’ and I should have known that. It is a point Tóibín discuses from his own point of view as a white queer witness to Baldwin’s life, though he treats it with greater understanding than I realised were that I showed in the gut reactions which resulted in my hesitation and delay in watching the film. It relates in part to why Giovanni’s Room, his queer novel, used only White characters. In neither case are these choices ‘inexplicable’ from the point of view of a Black queer man.

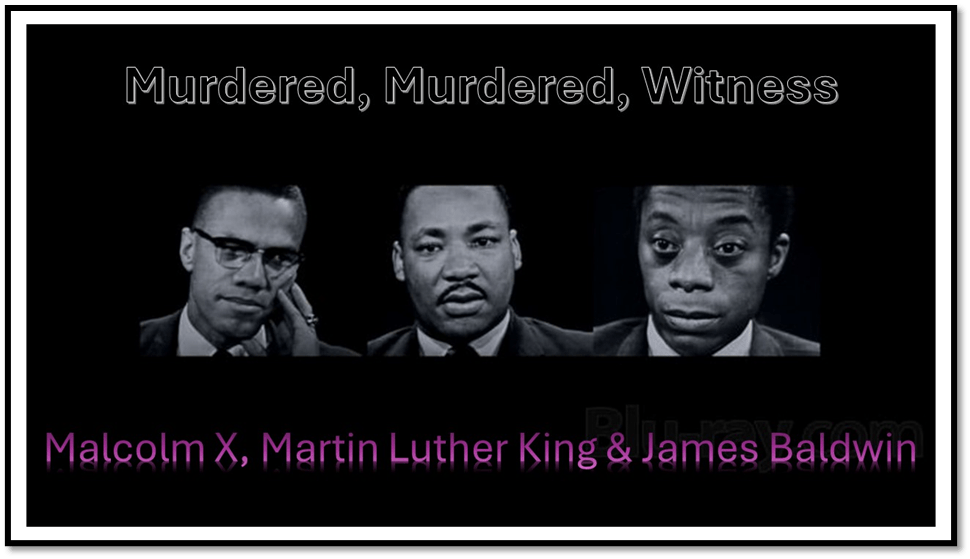

There are many possible explanations of why this film, and Baldwin at this time of his life, might focus on the extreme danger posed by White Racism and the violence of the present moment, not least his understanding that the analogies between White Racism and violence and those of homophobia and hetero-sexism were far from clear and direct ones. As such they were not pertinent in what was a kind of elegy to three men, all friends eventually and aware of Baldwin’s sexuality.

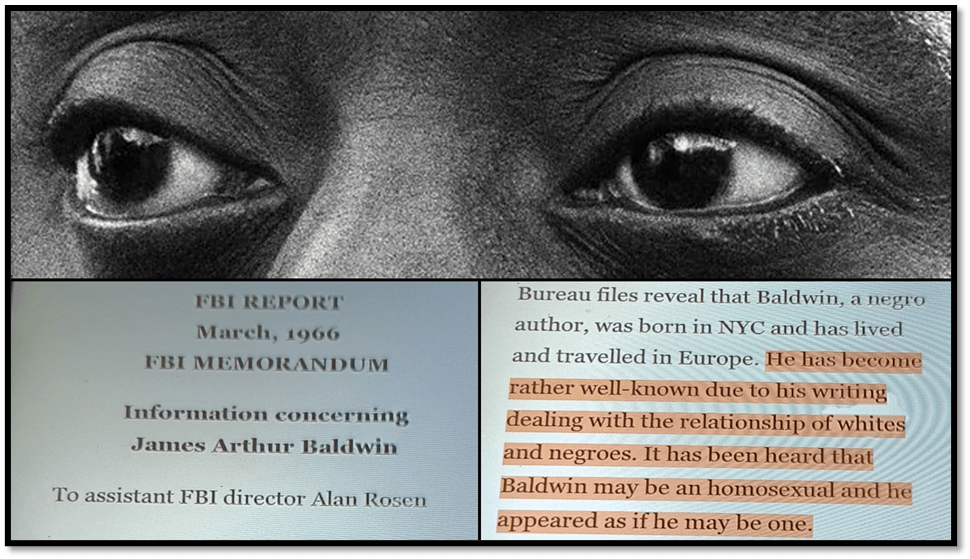

Moreover, to say “largely omits’ reference to his sexuality is to ignore the force of the fact that the film uses a caption from the FBI files on Baldwin showing that because ‘it was heard that Baldwin may be an homosexual and he appeared as if he may be one”, he was even the more so considered worthy of being listed as a ‘security risk’ and hated by Herbert Hoover, himself closeted queer but safely White, so that no-one much cared to fear him where there was indeed cause.

On top of this Baldwin cites quite casually in the film the names of his male partners at the times when events on the civil rights of Black people flared, including the Swiss bisexual white man, Lucien Jean Happersberger. After all, Giovanni’s Room could have left no doubt of Baldwin’s sexuality even in the public realm, and I Am Not Your Negro had specific work to do beyond the exploration of autobiographical intersectionality. This is a book with a specific ‘mission’ to covert those who might listen to him, whether on the Dick Cavett Show, or through his books. He used every form of rhetoric to be expected of a preacher’s son to fulfill that ‘mission’, a boy designed for the ministry in his father’s view, a fate explored in the wonderful early play Amen Corner. For a mission’ involves a ‘journey’ both to and from foreign places in need of conversion and a return to something you call ‘home’, although the alien and the homely can sometimes get confused.

The return ‘home’ begins as an exodus from artistic exile in Paris, where Giovanni’s Room was written and set, back to Harlem where his family still lived. He missed the way people who loved him and who had ‘dark faces looked at him in particular. And yet home feels unfamiliar, unhomely (unheimlich or uncanny), and he has become a ‘stranger’ to it. [3]

I missed the way the dark face closes, the way dark eyes watch, and the way, when a dark face opens, a light seems to go everywhere. ... Now, though I was a stranger, I was home.

Clearly his ‘journey’ and ‘mission’ required he take other roads, moving farther back in the time of his dark connections to a home in which he never personally lived: the American South. Which road can he take? ‘The “road” means my return South’, he says, continuing, in the rhythms of verse still: ‘It means, briefly, for example, seeing Myrlie Evans and the children’ (the wife and children of Medgar Evans and then on to those of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X). And then he clinches his sense of a mission. Indeed, he makes an analogy of his role with that of St. Paul the Apostle in the New Testament:

It means exposing myself as one of the witnesses to the lives and deaths of their famous fathers. And it means much. much more than that – a cloud of witnesses, as old St. Paul once put it.

The purpose of this is to redefine the meaning of Baldwin’s life in terms of a mission that is as religious in intent as the Apostle’s: a thing made precise by the context of his reference to the Saint, a Saint in whom he had no connection of faith in truth. The context in which Paul spoke of ‘a cloud of witnesses’ was in his Epistle to his coreligionists, the Christian Hebrews; the purpose of it to show them that both Gentiles and Jews could witness to the divinity of Christ and be numerous, putting pay to the notion of a chosen ‘race’ or ‘nation’.

Wherefore seeing we also are compassed about with so great a cloud of witnesses, let us lay aside every weight, and the sin which doth so easily beset us, and let us run with patience the race that is set before us, 2 Looking unto Jesus the author and finisher of our faith; who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is set down at the right hand of the throne of God. [Hebrews 12: 1-2.]

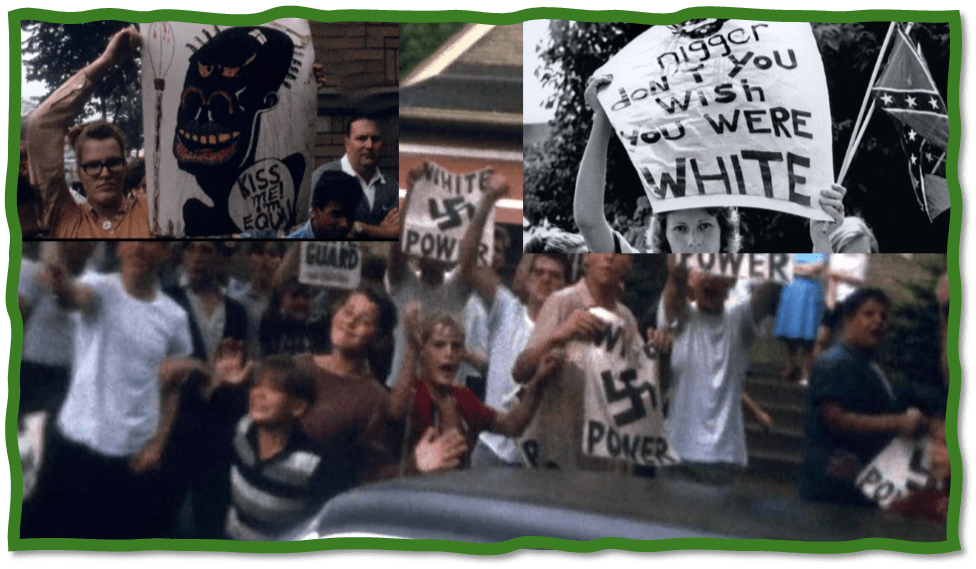

That the mission was one of the spirit not the body was plain to Baldwin, for to him, at the height of his pain at the loss of not only community leaders but personal friends, he needed to maintain, against even Malcolm X, one of the murdered men he was honouring that there was hope for unsegregated communities regardless of the colour of the skin, race or nation. Whilst this film shows the depth of racial hatred turned into action for ‘White Power’ (see the collages below) Baldwin’s rhetoric preaches – no other name suffices – that love must keep hope alive that just being White is NOT the cause of white hatred and violence to Black people.

He says, citing the physical, intellectual and spiritual beauty of his ‘young white / schoolteacher named Bill Miller, / a beautiful woman” that she ‘arrived in his terrifying life so soon’:

that I never really managed to hate white people.

Though, God knows,

I have often wished to murder more than one or two.

Therefore, I began to suspect that white people

did not act as they did because they were white,but for some other reason.

For him it was clear that though white and a woman, Miller too ‘anyway, was treated like a nigger’ / especially the cops, / And she had no love for landlords’. Baldwin was on root for a socio-economic and political explanation of racism that negated that hate should be returned for hate of the most violently performed kind. However his perception had a rigour that let no doubt that so much of the behaviour of a large number of Whites in the USA was monstrous, and that their conversion was as difficult as of that of demons and monsters.

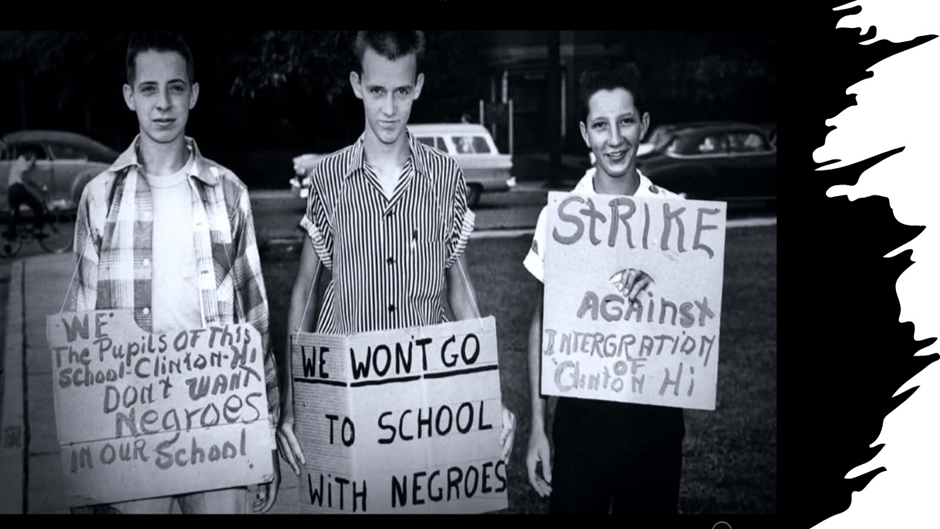

Nevertheless, he was determined to root it in the kind of love thought of as Christian but practised by so few Christians he knew. The heart seemed to have a battlefield already lost because of the refusal to admit to the pain of having been in the wrong, and for so long. Even children supposed innocent, could not be persuaded that their parents’ belief systems were not only wrong but monstrous, and making monsters of them. The photographs in this film are relentless.

The dehumanisation of White people is a consequence, Baldwin insists, of the dehumanisation of black people and the creation of a sub-category of the non-human that was untouchable when it asserted any right of quality in the way we treat, for example, a young women who might wish to get an equal education to a white person in a desegregated school. White boys who follow this girl make signs of devilish horns appearing from the girl’s head, yet Bobby Kennedy said of this very girl’s request, via Lorraine Hansberry and Baldwin, to have a personal escort to school on the day she was scheduled to enter one in the deep South, that it was “a meaningless moral gesture”.

The phrase from the film that uses the N—- word used otherwise to dehumanise Black people at the time is the one the film does not shy from using. This is defiant but not violent, it holds up a mirror to the ‘hate’ filled, even showing that ‘hate’ takes different forms – even humour but certainly pretended innocence, or a need to pretend that the hurt of projected hate is not felt by the Black people to whom it is directed. This is why Baldwin hated the pretended innocence of Doris Day and Gary Cooper, ‘two of the most grotesque appeals to/ to innocence the world has ever seen’ dancing in all-white and light places with all-white and light people.

Hate and smug ownership of one’s belief that Black people are happy and contented merely servicing White entitlement, the film’s illustrative clips and slides continually show, oft without commentary. The aim is by the constant barrage, the soul of White people might be shaken to see itself in a ‘glass darkly’, before going on to see Black People face to face, even James Baldwin, whom they deign to like for his talent.

And the need is for Baldwin to show that these instances of hate hidden and covered up relate to the most atrocious crimes. Hence his focus on the death of friends, even Malcolm X who he was in constant battle with intellectually, though he understood why he said, as we hear him doing in film clips: ‘following the ignorant Negro preachers, we have thought that it was godlike to turn the other cheek to the brute that was brutalizing us‘.

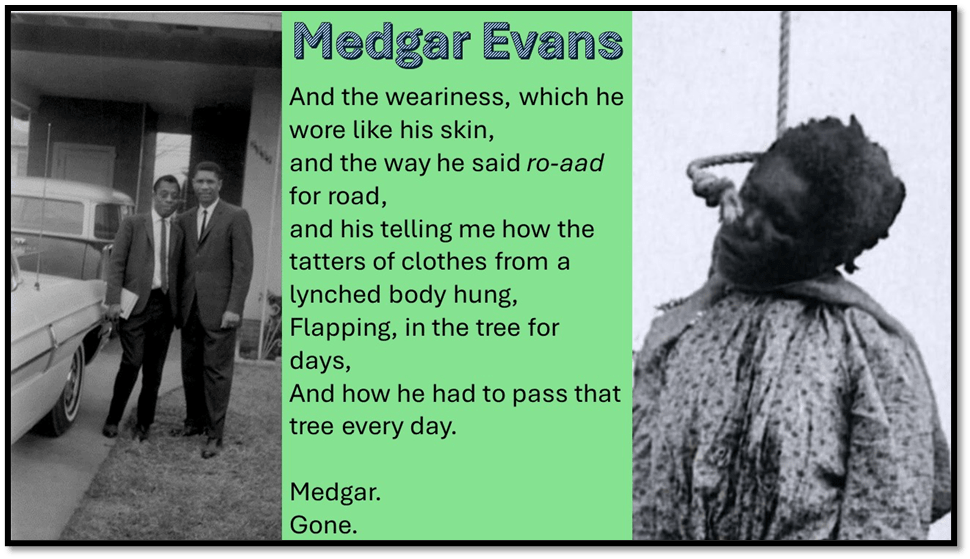

But the murder that pained most, or so it seems in the film, was his closer friend, made into the subject of a protest elegy by Bob Dylan that we hear in the film, Medgar Evers. It is this man who showed Baldwin, the writer himself claims, what it was to be a “witness” and how, though that excluded certain kinds of violent action associated with the Black Panthers and Black Muslim movements (who took up jihad against enemies and included Mohammed Ali although in non-violent jihad). Other action excluded was the over institutionalised conservative activism of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), of which Evers was a prominent member. Yet for a writer to be a witness, a writer of epistles like St. Paul for instance, was still ‘action’.

As Baldwin put it, and as Samuel L. Jackson reads for him beautifully in the film:

but I had to accept, as time wore on,

that part of my responsibility -as a witness -

was to move as largely and as freely as possible,

to write the story, and to get it out.

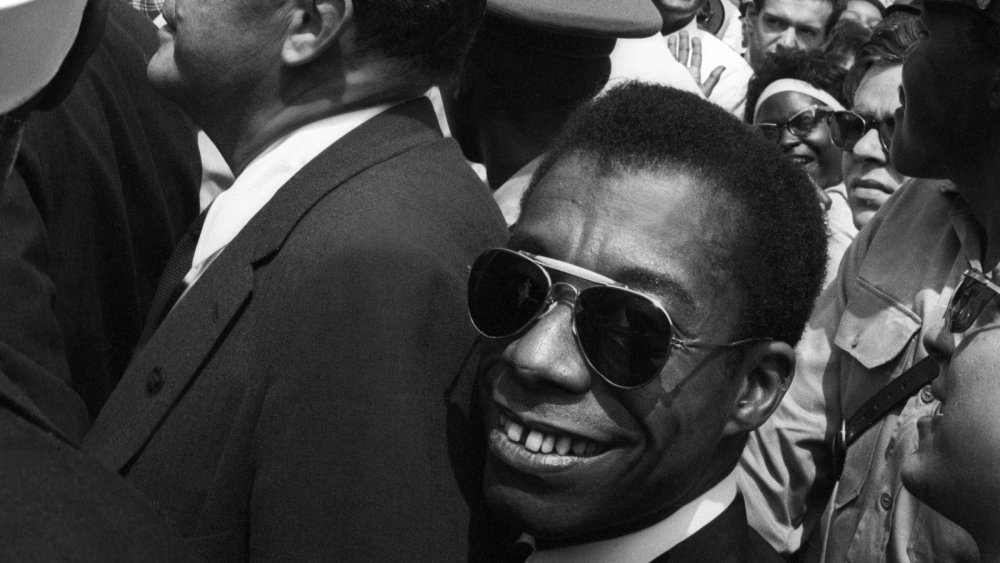

And Baldwin became a face recognised on TV as well as in a crowd, as the film shows us, and the stills above attest to. Medgar Evers is the most personal portrait in the film and extant text, his memories the most searing. I struggled with whether to include one of the pictures in the collage below, but in the face of White denial in the US, and of racists in the UK I have.

Wearing ‘weariness like a skin’ is not merely a beautiful metaphor if seen in terms of that picture a young Black man dressed by his murderers in a dress before he is brutally hanged. Baldwin uses the word ‘hung’ purposefully in the poem-like text quite aware I believe that the term ‘hanged’ was more appropriate for a ‘lynching’ except that ‘hung’ is exactly right if applied to ‘tatters of clothes’ that flap where they are passively hung (rather than actively hanged like the body they clothed). This is writing that truly bears witness to the inhuman and evil. To wish merely NOT TO SEE these things is a p[retense to ‘innocence’ not unlike that implied by Doris Day’s presence in ‘White films’.

Of course, a ‘cloud of witnesses’ does exist to the deaths the film covers – the still from the film below is telling, especially in proximity to the voice-over supposed to be that of Baldwin saying the words below; which bears witness not only to communal spirit but its means of supporting us in suffering, and in exerting strength thereafter:

I did not want to weep for Martin;

tears seemed futile,

But I may also have been afraid,

and I could not have been the only one,

that if I began to weep, I would not be able to stop.

I started to cry, and I stumbled.

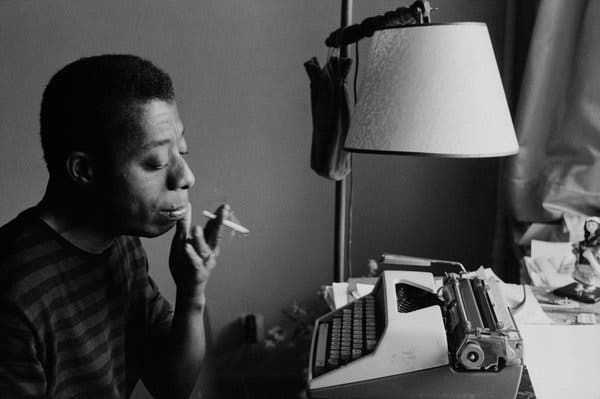

Sammy grabbed my arm.

Meanwhile, we have the writer in characteristic pose at his typewriter, daring to parody even the American National Anthem as well as the emptiness in the hearts of its writers, who knew they wrote of lies, that they were not capable of, nor willing to, turn into truths lest they be accused of ‘meaningless moral gesture’.

Thus he mourns, like W.B. Yeats and Wordsworth, a political lie replacing what should be an ideal flowing on the hear and through the veins:

... the lack, yawning everywhere in this country,

of passionate conviction, of personal authority,

...

To look around the United States today

is enough to make prophets and angels weep.

This is not the land of the free;

it is only very unwillingly and sporadically, the land of the brave.

Baldwin oft illustrates this through the iconic figure of John Wayne who helped treat genocide as if it were the White Man’s Right. Show John Wayne with his gun aimed to the side of you, as a clip in this film does, ‘you’ can be certain if you are White that it is aimed at an ‘alien’ human, whose home you appropriated, to rescue you from retribution you personally don’t deserve, for we’ve ‘made a legend out of a massacre’. The Black man knows it is aimed at him. What John Wayne celebrates is that:

immaturity is taken as a virtue, too,

So that someone like that, let's say John Wayne

who spent most of his time

on screen admonishing Indians,

was in no necessity to grow up.

This is a good point to take leave of a blog on this wonderful film, before thinking of a future blog (but not perhaps the next) about Colm Tóibín’s On James Baldwin. That writer has much to say about the way that Baldwin had taken ‘experiences and emotions that I recognized and then utterly transformed them’. He did this with the mixture in particular of a style taken from the Jamesian novel of shifting consciousnesses, or points of subjective view, and one from the Scriptures and teaching them. What he achieved, Tóibín believes, is a way of writing in which:

… the heightened emotion around ritual and religious belief strayed into same-sex desire, rendering the latter as unfathomable and as beguiling as the former, but more dangerous’.

We are meant to believe according to The Atlantic that same-sex desire does not enter into this late text and the fiming thereof. However, I do not not know how to read this piece about a formal encounter at a lecture, and during a lecture of Baldwin with Malcolm X. It is not an interaction that is in any way queer in embodied practice, and would not anyway, by all accounts have been amenable to Malcolm X in this form, but in Baldwin’s words there is much that can be nothing other than ‘heightened emotion around ritual and religious belief’ that has ‘strayed into’ one-sided same-sex desire, rendering the latter as unfathomable and as beguiling as the former, but more dangerous’:

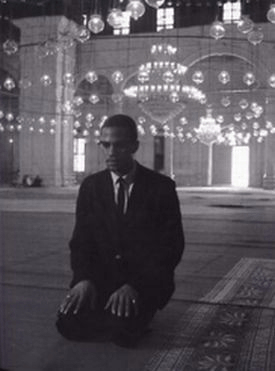

I first met Malcolm X.

I saw Malcolm before I met him.

I was giving a lecture somewhere in New York.

Malcolm was sitting in the first row of the hall,

bending forward at such an angle

that his long arms nearly caressed the ankles

of his long legs, staring up at me.

Malcolm X – long legs and long arms in prayer

The physical details are true and there is something of ritual attention in the description of the man listening to Baldwin, for the first time stood tall over X, for Baldwin was a short man. However, there is something too in the ‘caressing’ of the self that is auto-erotic in the way in which Baldwin projectively identifies the desire in Malcolm X to share love. This need not be sexual nor auto-erotic but it borrows the energies of both to bond these men, whom, as Baldwin rightly says, were both ‘sufficiently astute to distrust’ each other politically. This is not about sex but it has everything to say about true love of a very spiritual embodiment crossing between militant and writer activists, Muslim and atheist in Christian mode.

Do see the film. It is truly wondrous and stunning. It made me weep, though I treasure manly resistance to tears not at all, but even if YOU DO …. Let’s see!.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxx

_______________________________________________

[1] James Baldwin (Compiled and edited by Raoul Peck) [2017] I Am Not Your Negro Penguin Classics.

[2] Dagmawi Woubshet ‘The Imperfect Power of I Am Not Your Negro‘ in The Atlantic (Feb. 2017). https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/02/i-am-not-your-negro-review/515976/

5 thoughts on “‘The “road” means my return South’. The mission that was the life and witness of James Baldwin. This blog reflects on the great film ‘I Am Not Your Negro’, with the writing of Baldwin himself.”