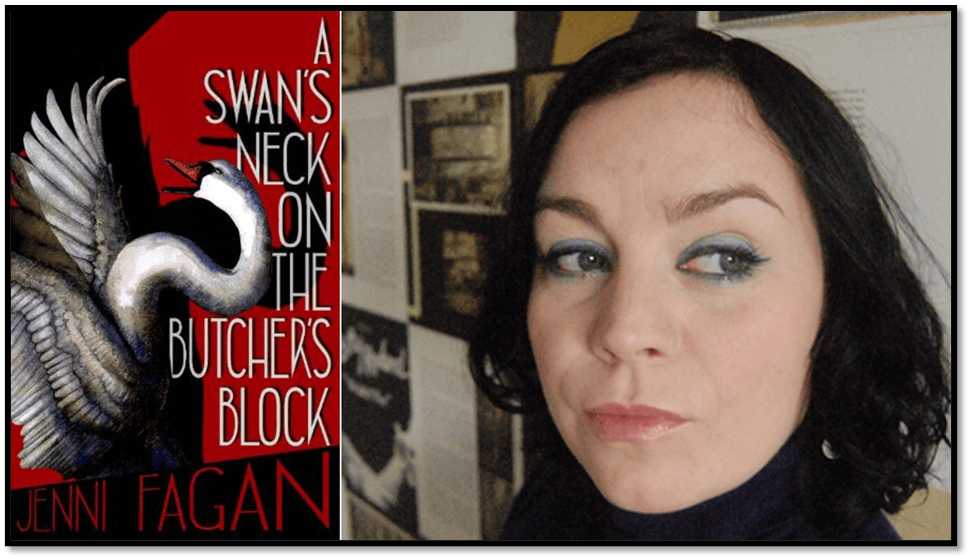

In a poem called There’s a Problem in the Arts, the voice of a lyric says of literature that, ‘it’s an industry / for cunts! / Where’s the fucking poetry in it?’ [1]. What is that problem? This is a blog on Jenni Fagan (2024) A Swan’s Neck On The Butcher’s Block Edinburgh, Polygon.

It is possible, I suppose, that a swan lying on a butcher’s block looks at the thing that will kill it, vindicated by the superiority of its passion over the cold arts of killing, eviscerating and filleting that will finish off that swan. There will always be the moment when he, the butcher of her glory has to turn from the deadly arts of which he is proud, in which he has ‘real promise’ to excel, has, even as he tries to drown out the meaning of his act, and, as he:

turns that radio up, looks into the clear red blood of my eyes.[2]

Are those eyes red with the visceral release of inner blood on the swan’s murder or with anger (or both)? Does he know at the moment, as the swan thinks he does that she has her own weapons:

wings ruffle, shoulder blades sharper than a human’s. I could break a leg with little effort. He knows it, he knows it …[3]

Repetitions that fade out at the end of line might be assertive but are more likely to be self-questioning. The Butcher could be a poem about rape but is possibly about the rape of poetry, of its inner strength, testing whether it survives masterful severation of limb from limb, but perhaps first the head that might sing as it dies, of a living body of art: that moment where Wordsworth claimed: ‘We murder to dissect’.

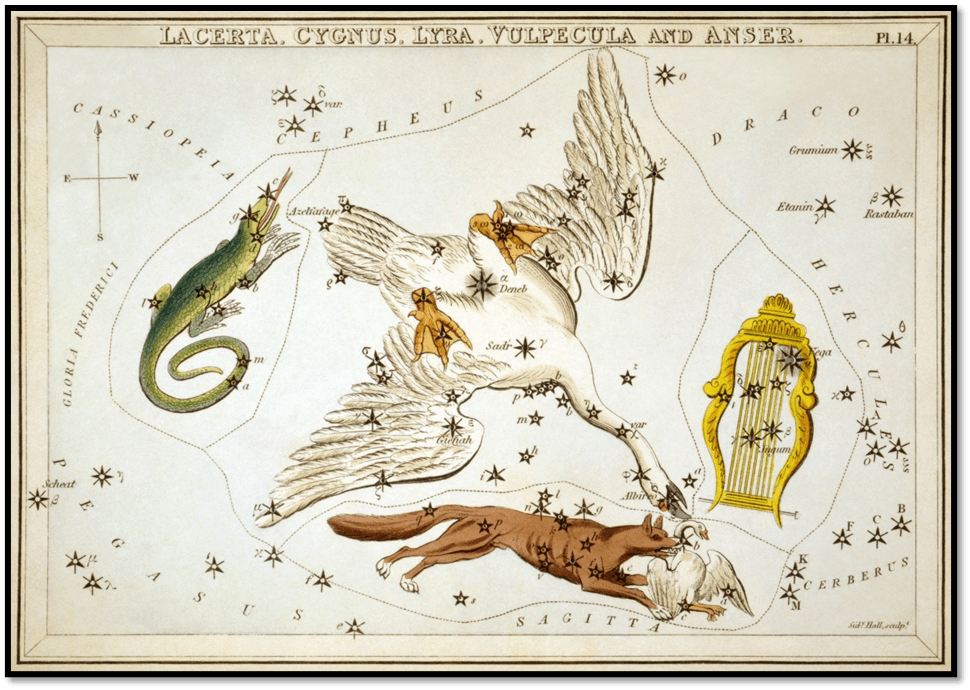

Swans have a literary reputation for saving the articulation of their art for one first and last song as they die, Fagan’s poem Orpheus tells of how Orpheus ‘became a swan’ (Cygnus), taking with him his lyre (Lyra) to form asterisms (a word she uses beautifully correctly) within constellations, Cygnus being the constellation ‘known as the Northern Cross’.

Cygnus as depicted in Urania’s Mirror, a set of constellation cards published in London c.1825. Surrounding it are Lacerta, Vulpecula and Lyra. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cygnus_(constellation)#/media/File:Sidney_Hall_-_Urania’s_Mirror_-_Lacerta,_Cygnus,_Lyra,_Vulpecula_and_Anser.jpg

Yet even Orpheus, valedictory of poetry through its icon, saves a moment to ensure we know that only the poet may know about the true shaping of a poem, including its ethical function, of which critics may lose sight.

she’d like to be gliding across the water lit up as it is by night and stars, yet the others, well, what do they know about asterism? Or ethics, too, for that matter.[4]

The assertion of ethical superiority comes as a shock, even rhythmically, in the last line. It obscurely casts a doubt on the right of any ‘others’ to claim knowledge of the swan and her hidden meaning, even that ‘lit up’ on its surface, for they look beyond her life. It’s worth considering how the sensibility here compares with late Romanticism in Tennyson for instance, whose poem The Dying Swan takes on the ambiguity that a personal lament that starts with weeping for the loss of its own life might, because of the jubilation implicit in its form as song both in the ears of a waste land, and even the inhabitants of a city or nation become a glorious exaltation of each particular form of continuing life. It’s worth looking at the whole poem:

The plain was grassy, wild and bare,

Wide, wild, and open to the air,

Which had built up everywhere

An under-roof of doleful gray.

With an inner voice the river ran,

Adown it floated a dying swan,

And loudly did lament.

It was the middle of the day.

Ever the weary wind went on,

And took the reed-tops as it went.

Some blue peaks in the distance rose,

And white against the cold-white sky,

Shone out their crowning snows.

One willow over the water wept,

And shook the wave as the wind did sigh;

Above in the wind was the swallow,

Chasing itself at its own wild will,

And far thro' the marish green and still

The tangled water-courses slept,

Shot over with purple, and green, and yellow.

The wild swan's death-hymn took the soul

Of that waste place with joy

Hidden in sorrow: at first to the ear

The warble was low, and full and clear;

And floating about the under-sky,

Prevailing in weakness, the coronach stole

Sometimes afar, and sometimes anear;

But anon her awful jubilant voice,

With a music strange and manifold,

Flow'd forth on a carol free and bold;

As when a mighty people rejoice

With shawms, and with cymbals, and harps of gold,

And the tumult of their acclaim is roll'd

Thro' the open gates of the city afar,

To the shepherd who watcheth the evening star.

And the creeping mosses and clambering weeds,

And the willow-branches hoar and dank,

And the wavy swell of the soughing reeds,

And the wave-worn horns of the echoing bank,

And the silvery marish-flowers that throng

The desolate creeks and pools among,

Were flooded over with eddying song.[5]

Fagan revisits that in another short lyric Swan Song, but returning to Tennyson’s Greek sources, for all I know she may miss Tennyson out entirely. That little lyric recalls the myth of the Greek’s notion of the formation of Cygnus as ‘a constellation’, which may recall the rape of Leda by Zeus in that form too, as well as Orpheus. In the short lyric there is no overt irony about the fact that a lament over her death becomes taken as something ‘more beautiful’ than anything else in the swan’s life, except that it’s difficult to read the last two lines in any way other that with at least a hint of bitterness still sounding in the joy, perhaps at the shallowness of those who retail the story without reference to the swan’s own feelings:

It's said she never sounded more beautiful Than on the last, smooth note.[6]

Perhaps Tennyson is part of the problem (as are the Greeks for the same reason) that they found an idea of literature as being on the cusp of the personal and the public, whilst finding through the institution they make foundation of, ‘Literature’, a means of eradicating the life of the poet, and perhaps particularly when that poet sings such songs of severed connection to the sustaining things of normative life that, even where they limit, sustain and nourish. This is so of any norms, such as the homonormative ones explored in a very funny poem Queer Dating, where the poet remains Mariana in a moated grange despite having chosen queer preference in her dating [7]

It is explored more in another brilliant comic poem Swan, who has a list of ailments to lament, from water retention making her look fat, and thus be asked to accept being ‘radically fat’, restricted mobility, and joint pain (at each of her vertebrae). As a female swan she is called a pen, in which the swan-lyricist finds another half-joke (the word ’funny’ is used ambiguously as strange and comic) for she does not write as a kind of preference but as a necessity that also causes her pain. It is a fine poem, the joke being that a pen can also have to be a heavy typewriter, even more punishing for an arthritic swan to jab at;

On eBay she scans for a typewriter, It has to have keys big enough to jab at with her wings, As a female she is called a Pen, Which is funny, to her, as she picks it up, to start writing.[8]

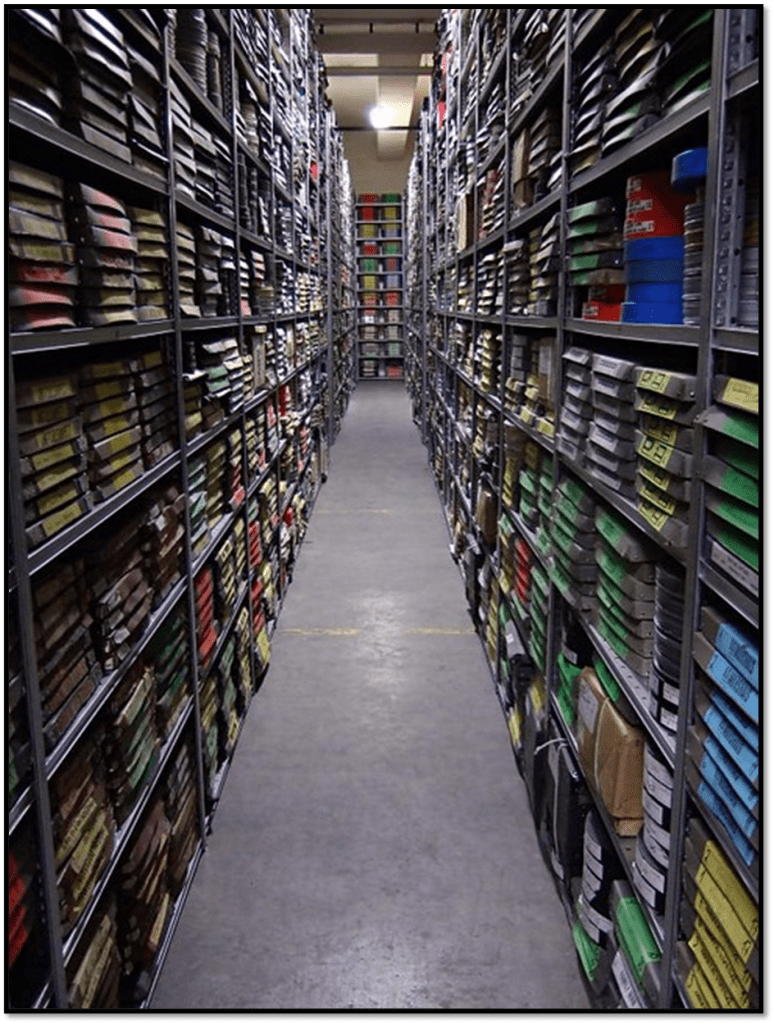

But this volume is painful, but more so for its embodied pen (or typewriter) because it deals with loss it can only hint about and dare to be understood, but DEFENSIVELY fears it will be misunderstood. I capitalise ‘defensively’ for that is a feature of the poems sometimes. It deals with the past of an ‘Urchin’ and ‘Ootlin’, bereavement of a father less almost unknown to her during the time he might have been there for her (see Memorial and Winter Solstice), of a mother who was, in the end, a victim, but who left her only the traits, or so ‘they say’, that makes people recall her as ‘a fanged thing’. The lyricist does not want to be a victim though she carries with her what her foster mothers saw as ‘madness’ and against all the barbed nuance of all this she tries to defend herself.[9] All of this is bound up with the delayed publication of Fagan’s memoir Ootlin, of which:

On publication day my books sit in a warehouse in the dark, very much alive, deadly as they ever will be, …

A book like that is death as well as life because it drains the chances of ‘doing something’ that isn’t about the manipulation of one’s life by subjects on which others discourse and have to put in scare quotes for that reason: “…,/ do something, just one fucking thing … / that isn’t looking at ‘care’ or prior ‘drugs’ or ‘assaults’ / on my file, or the tattoos on my arms, / or the fatness of my arse, / …” , It defends against others but it defends against a life that has written itself in all its wronged-ness and wrongness.[10]

And then there is that extraordinary attack on ‘Literature’ from which I title this blog, There’s a Problem in the Arts. It is difficult to read if you have learned to love and need literature and the arts as either a prop or a source of material on which to meditate, and find solace in its monstrously complex nuances in which its agents (writers and so on, get tied up with readers, doing real reading. The problem with this poem, is that its anger does not distinguish between lovers of arts except by their degree of awfulness, starting with ‘Abusers’ to the entitled middle-class, ‘entitled as they are made to feel as much to the arts as the certain knowledge of their specialness created by their ‘mummies and daddies’. Literature is the poem spits at those who ‘spit on strangers’ souls’, which I take to be writers, and whose real object of desire is to:

Say it’s only me me me me me me me me me me meeeeee eeeeeee eeeeeeememememmee – it’s an industry for cunts! [11]

Egotism, narcissism, entitlement, normativity drive people to hide ‘their posh qualifications / so they can act like they are authentic, or working class’, preferring memes hidden in their selfish search to seeing ‘the purest talent’ (again presumably the writer – one of those of whom the lyricist says: ‘I’ve seen so many of our greatest writers be erased / by all of the above’). This is a poem so defensive its anger becomes almost rank with the sense that every other person in the world, or at least the ‘industry’, of the arts is out to kill the writer, become the butcher who puts the swan’s neck on his block and severs its head, as Orpheus’ head was severed, by his own followers.

It is hard to read and maybe should be read as a symptomatic rather than a declarative poem, one that fits with the terrible symptoms of self-loathing and other-loathing (‘Nast gaze to how many eyes?)’in I Don’t Think.[12] The problem is that symptomatic poems are rarely only this and certainly not only symptoms of mental distress or illness, for they also bear truths that are true for all of us at all times in all spaces. There are many such poems. Try They Found Something In My Blood.

Maybe you should avoid the term ‘symptomatic’. I think so, except I know no other term. The point of these poems is any feeling you get from them is likely to be also a symptom of something wrong with the reader, society and its institutions. When the lyricist condemns the ‘industry’ by asking: ‘Where’s the fucking poetry?’ in literature has it has become, we should feel the pain of that too. For it is a sickness in our blood too, an infection that might spread, unless we chase the ‘poetry’. But of the latter there is still a lot in this lovely volume: Badger, for instance.

Dearest darling badger moon – I am tethered to you …. by particles of me.

But move on a few pages to this beautifully funny Let’s Bang On About the Moon and you get my point. Nothing stops where it is, even ‘Poets and the fucking moon’.[13]

You could read and reread this volume for ever. It never stays still – allow its tone to vary in your head and you’ll catch its brilliance.

Shelley banging on about the Moon.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] There’s a Problem in the Arts In Jenni Fagan (2024: 4) A Swan’s Neck On The Butcher’s Block Edinburgh, Polygon, 4f.

[2] The Butcher In Jenni Fagan (2024: 26) A Swan’s Neck On The Butcher’s Block Edinburgh, Polygon, 25f.

[3] Ibid: 25

[4] Orpheus in ibid:13, 13.

[5] Tennyson (first printed 1830) The Dying Swan. Available at: https://genius.com/Alfred-lord-tennyson-the-dying-swan-annotated

[6] Swan Song in ibid:34, 34

[7] Ibid, 53

[8] Swan, in ibid:39, 39.

[9] Ibid: 12

[10] Ootlin in ibid:3, 3.

[11] There’s a Problem in the Arts In ibid: 4, 4f.

[12] I Don’t Think In ibid: 57, 57 – 59.

[13] See ibid: 84 & 100 respectively

One thought on “In her new volume Jenni Fagan has a poem called ‘There’s a Problem in the Arts’. What is that problem? This is a blog on Fagan’s (2024) ‘A Swan’s Neck On The Butcher’s Block’.”