Amy Liptrot’s ‘The Outrun’ performed by the Lyceum Theatre Company for the Edinburgh Festival at Church Hill Theatre on Thursday 22nd August 2024, 8.00 p.m.

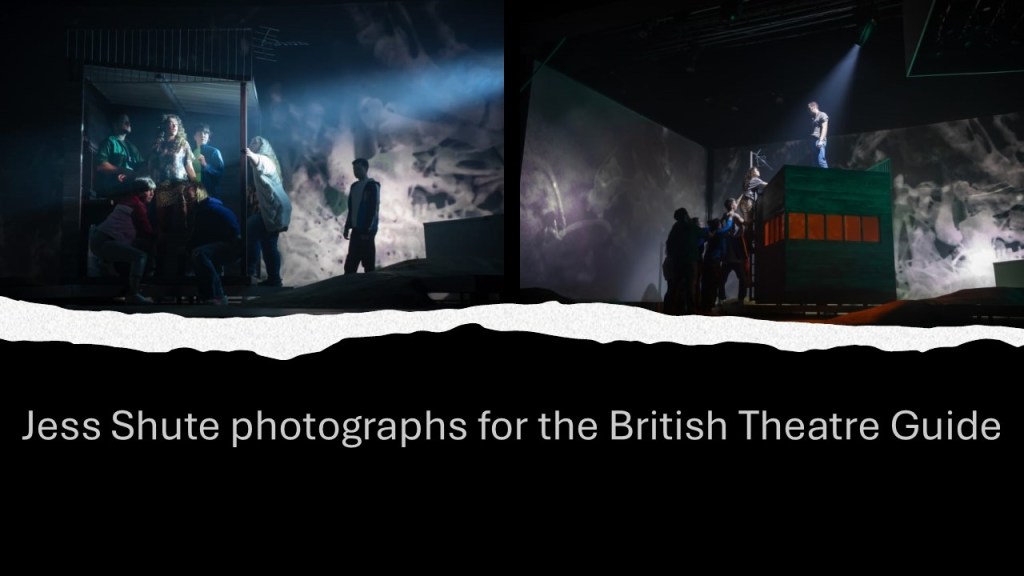

I might as well start with publicity images from the space because in truth, getting there to the actual space on time, where I might have taken my own was a problem. I set off in goof time confident I could find my way over the Meadows to the road on which Theatre stood. Having gone what turned out to be very much the wrong way for so long, I eventually bundled into a taxi and arrived just in time.

Earlier I wrote about the book on which this play is based. Find that blog at this link.

Many of the themes I recognised in this book I found in the play but sometime transformed not only in their mediation, as cannot and must not be avoided, but in their meaning. This was much more a play that conformed as a result to the Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) Recovery paradigmatic structure than the liberatory book does.

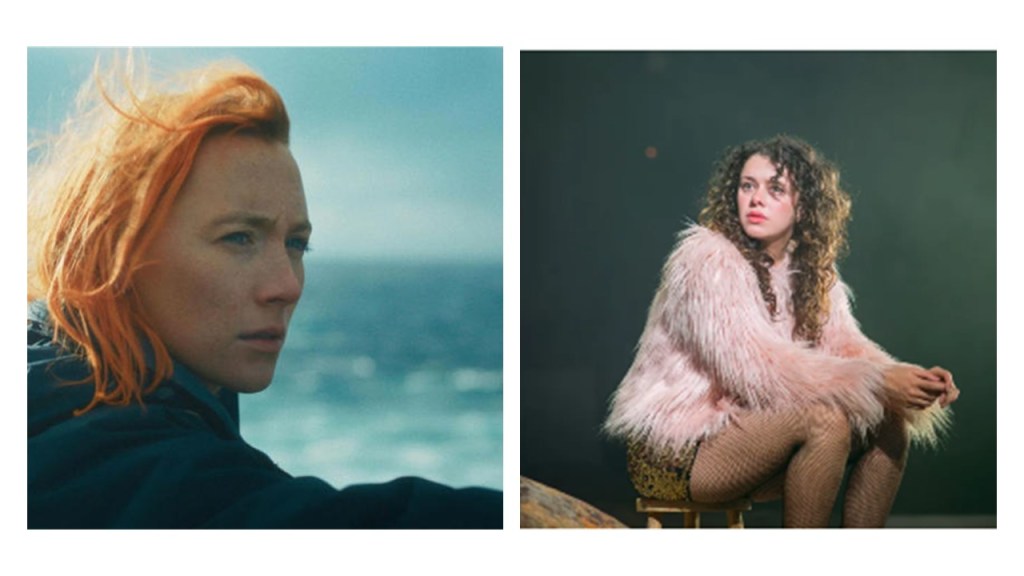

But first of all for the totally positive, for this is a play you ought to struggle to see. In the film of The Outrun which comes out in September with an inter-cutting narrative of scenes in London and the Orkneys, there is a reason an actor of the maturity, pull and earning power as has Saoise Ronan is selected. Much of the success of any artwork depends on the credibility given to this role.

But the actor in this play is superlative.The character who is Liptrot’s personal and narrator becomes it is reported, ‘Rona’ played by Saoirse Ronan [left above] but merely ‘Woman’, as named in the programme at least, in tne play and is enacted by Isis Hainsworth [right above]. Isis is superlative, whether playing the young child befriended by Boy (the play eradicates Amy’s younger brother and Boy takes his symbolic and functional role and that of other friends in Orkney) a young woman or one become older. Beyond the generalization of young boy characteristics by Seamus Dillane, brilliant as Boy, the roles in the play never become purely stereotypical. They are not even the kind of types required by moral allegory, which I though MIGHT be the approach taken, though the AA group meetings show how addict stereotypes can be and are manufactured, in ‘real life’, as well as in this play.

Boy though is easily distinguished in the cast ensemble picture below, not only by thrir sailor tee-shirt but by their hogging posession of the tree swing that helps place his boyish role, though Woman [as a girl] uses it too.

Ainsworth and Dillane are brilliant in their child roles, knowing how to look as if they actually were sitting on a sea shore as children do, legs stretched and shoe soles prominent, whilst a convincing visual behind them sets the scene.

The cast often too appear in ensemble enacting various communities in which Woman becomes absorbed, and hence each actor is fluid taking on many charaacters as well as donetime being their amalgation. Thus a person who is a random member of an AA group develops to take on several roles as they are in the book by Amy Liptrot, even Dee, the only other AA member on Papa Westray. This figure is a strong if an internally inconsistent one, somehow though Alison Fitzjohn brings individuality out of type by means that seem fabulous. The play opens ith the whole community arising from the inclining rock like structures that are scattered over the stage like a community from the past coming back to life, moving with a zombie shuffle.

Community is not however a coherent theme in the stage version as adapted by Stef Smith as it is in the book. Often community members are invented to play roles in Woman’s life, or their scope enlarged in order to allow narrative to flow in dialogue. But that can change the meanings of the narrative, as does, for instance, the proffered love interest in the play ,of Scientist played by Reuben Joseph, invented for Woman on Papa Westray. This is not the innovative empowerment of Amy in the book where female appetite for more than relationships alone is vindicated. But more of that later.

The Royal Lyceum Theatre Company’s, Vicky Featherstone, is an amazing director and the scenes of social interaction are ones in which she excels, here often choreographed, with movement coordination by Vicki Manderson as much as directed, brilliantly using both original and cover music and patterned sound, even chants, as composed by Luke Sutherland. Much is done in the play by innovative us of the stage constantly morphed into otherness by lighting, sound and projected moving film or stills. Orkney is soft and moist and green. London is lights and addiction. Back in Orkney, she feels more like a stranger than a returning native. She struggles to find her way forward into a new mode of being.

The scenes in which Woman meets her lover, Ross Watt, were haunting scenes in which the lighting art of Lizzie Powell was at its best. Sometimes the lover were cast in monochrome melding in danced movement so wild it excited every sense. Here in blue:

And here in purple.

Milla Clarke’s set design was masterful especially given the space limitations on this far from huge stage, especially for a company accustomed to the Lyceum. Enhanced by background film or stills of beach stones or underwater flora, coloured light made scenes that either diversified the episodes available at any one time on the stage or bathed in uniformity. A shed looking structure served as indeed that, or a barn or the interior of a cottage, a high structure of any kind, rock or cliff, on which to stand. Costume (Sophie Ferguson) came of its own in such sets.

The Jess Shute photographs used here are good, but I so wish I could have taken some of my own.

The ones above show the most moving scene of the play in which Woman’s lover (called ‘Friend’ in the programme) rejects her after they have split as a live-in couple making it clear that an alcoholic offers only co-dependency not love to another, co-dependency, of course, on the alcoholic’s alcohol consumption. Here’s an enlargement of the beginning of that episode. The theatrical proxemics are remarkable

Love relationships and breakdowns ate not only well acted by persons but also by by the whole of the theatrical bag of tricks. Perhaps my collage below tells that tale

But when all is said and done the night belonged to Isis.

I suggested however above that there are differences in the theatrical adaptation that for me considerably lower the effectiveness of the narrative as both a story of female empowerment and as a qualitatively different account of recovery from alcohol. The adaptation is much nearer to the standard pattern of AA recovery narrative paradigms than to Liptrop’s novel defence of the appetite for ‘more’ and the rescue of the desire to ‘live on the edge’, but an edge that releases women from passive stereotypes without trapping them in alcohol, possession by men or the need to party.

The narrative of the adaptation has a classic scene where Woman pours the dregs of a ‘washed up’ bottle of vodka over the edge separating land and sea to symbolise her self-rescue by abstinence. This is not the feel in Liptrot, where abstinence is merely a stage in the liberation of female appetite for more meaningful and socially renewing exciting events [see my earlier blog linked at the top of this blog]. It was ever likely that adaptation to other media would reduce the innovative in Liptrot’s original and originating treatment of the subject of Recovery and return to use of the stereotyped motifs and tropes of Recovery narratives. Anna Clark reviewing the film version says:

As the film progresses, the flashbacks become more disturbing – we join in Rona’s horror as she wakes up with no memory from a violent, drunken night. It all feels horribly believable, unlike many an onscreen alcoholic episode. Ronan is as mesmerising to watch as ever, whether in self-destructive mode or in a subdued depression, wondering if she will ever be happy again. [1]

In the play, Liptrot’s intelligent resolutions give way because the conventional treatment of recovery narratives as about the ups and downs of recovery from dependence on a ‘life on the edge’ to the stasis of a kind characterised by abstinence, whose boredom has to be accepted, at least sets a conventional narrative ending with much highly dramatic sturm and drang along the way.

A review of the play by Dominic Corr actually praises the adaptation for doing exactly this with Liptrot’s text, characterising the latter by implication as less heightened and emotive.

Isis Hainsworth’s central performance, known only as the Woman, is not just engaging but also often poignant. Her role does much to elevate Liptrot’s memoir to necessary heights and freshness. Smith’s interpretation of the memoir’s addiction and eventual recovery serves as a perfect backdrop for Hainsworth’s performance, which transitions from energetic to desperate, never leaving the stage in a staggering feat. [2]

Nevertheless, Corr also says that this effect paradoxically makes the play colder than the book, and I think he has a point:

The stripped-back sentimentality makes for a refreshing change of pace, but it also leaves a coldness to the entire affair, accentuating the stark contrast between the two elements. [2]

Of course it may be that Corr means no more nor less than W J Quinn in The Quintessential Review. Is the idea of a cold contrast the same as dramatising a ‘mundane reality on stage’?

This is a remarkable undertaking, an audacious attempt to reach inside a life to spill out all of its magnificent, sensational, terrible, and mundane reality on stage. [3]

But Quinn is the more interesting critic because their review hangs on something that Liptrot does with great beauty and balance in her text: that is to integrate the interaction of the external life of human beings with the processes and dramas of their inner lives.

Catherine Henry Lamm in The British Theatre can have the last word for she is brilliant describing the mode of theatrical telling that is used, actually making me see something I might not otherwise have seen in the play about the simultaneous use of one small stage space to show both states of drunken exuberance and the contemplative reverie of the Woman once she is sober. Lamm’s words are that Featherstone has ‘created these two worlds of extremes in the same space. This is a new way of telling stories’. However what she goes on to say merely emphasises my point that the play misses the point about the role of the play to become a utilitarian tool enabling non-alcoholics to understand the real difficulties of working through the Recovery narrative on the way to their goal of abstinence

The Outrun is beautiful and painful. We have so much to learn. We learn about ourselves and the “them” in our lives, the addicts and mentally ill. We need to keep thinking about it and talking about it so we better know what to do about it. [4]

Whether, now the Festival is over, The Outrun will play again in theatres, especially once a major film has appeared in the cinemas (from September 27th) but if it is, see it. It is a moving and theatrically exciting experience and tells an exciting story. My objections are based entirely on strengths in Liptrop’s account that are not fully credited by being ‘theatricalised’, but it is not the role of either theatrical or cinematic adaptation to serve the book that prompted their versions of it. These alternative art forms must use their different resources to follow themes suitable to their own medium and those resources. The play at least has shown well that it has done exactly that.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx

____________________________________

[1] Anna Smith (2024) ‘The Outrun review: “Saoirse Ronan is exceptional in this affecting drama about addiction and hope”‘ in MSN reviews available at: https://www.msn.com/en-gb/entertainment/news/the-outrun-review-saoirse-ronan-is-exceptional-in-this-affecting-drama-about-addiction-and-hope/ar-AA1oVaY5?ocid=BingNewsSerp

[2] Dominic Corr (2024) ‘Review: Edinburgh International Festival 2024 – The Outrun, Church Hill Theatre’ in Cor Blimey (online) (09/08/ 202) Available at: https://corrblimey.uk/2024/08/09/review-edinburgh-international-festival-2024-the-outrun-church-hill-theatre/

[3] W J Quinn ‘EIF Review: The Outrun’ in The Quintessential Review [4th August 2024] available at: https://theqr.co.uk/2024/08/04/eif-review-the-outrun/

[4] Catherine Henry Lamm (2024’ ‘Review’ in The British Theatre Guide (online) available at: https://www.britishtheatreguide.info/reviews/the-outrun-hill-church-the-23533Edit

2 thoughts on “Amy Liptrot’s ‘The Outrun’ performed by the Lyceum Theatre Company for the Edinburgh Festival at Church Hill Theatre on Thursday 22nd August 2024, 8.00 p.m.”