Parody, pastiche, play and fun are probably enough. But Ferdia Lennon’s (2024) Glorious Exploits has more; a haunting desire to find fixed identities of sex/gender, sexuality, family and nationhood wanting. My blog states the case for liking this novel differently.

Anna Bonet, the Senior Writer at the i newspaper argues that if ‘novels that re-imagine ancient Greek stories’ are now a genre in themselves, Glorious Exploits by Ferdia Lennon ‘turns the genre on its head’.[1] I agree entirely though I find that overturning more than at the levels of well-written parody, pastiche play and fun. However, the novel has all of these estimable qualities. Like me, Killian Fox sees both more than the fun, and the fun too, in his critique. He also sees as well more of elements, at least, of historical accuracy in the plot, for he tells us (obviously a classical scholar too) that: ‘There are accounts in Plutarch of Athenian prisoners in Sicily trading lines of Euripides in return for food and drink or even freedom’. But he also sees ‘something that is not rendered just ‘funny’ or ‘comic’:

The novel is raucously funny – Lampo is a brilliant comic creation – but Lennon, a classics graduate, blends the laughs with tragedy of the blackest pitch.[2]

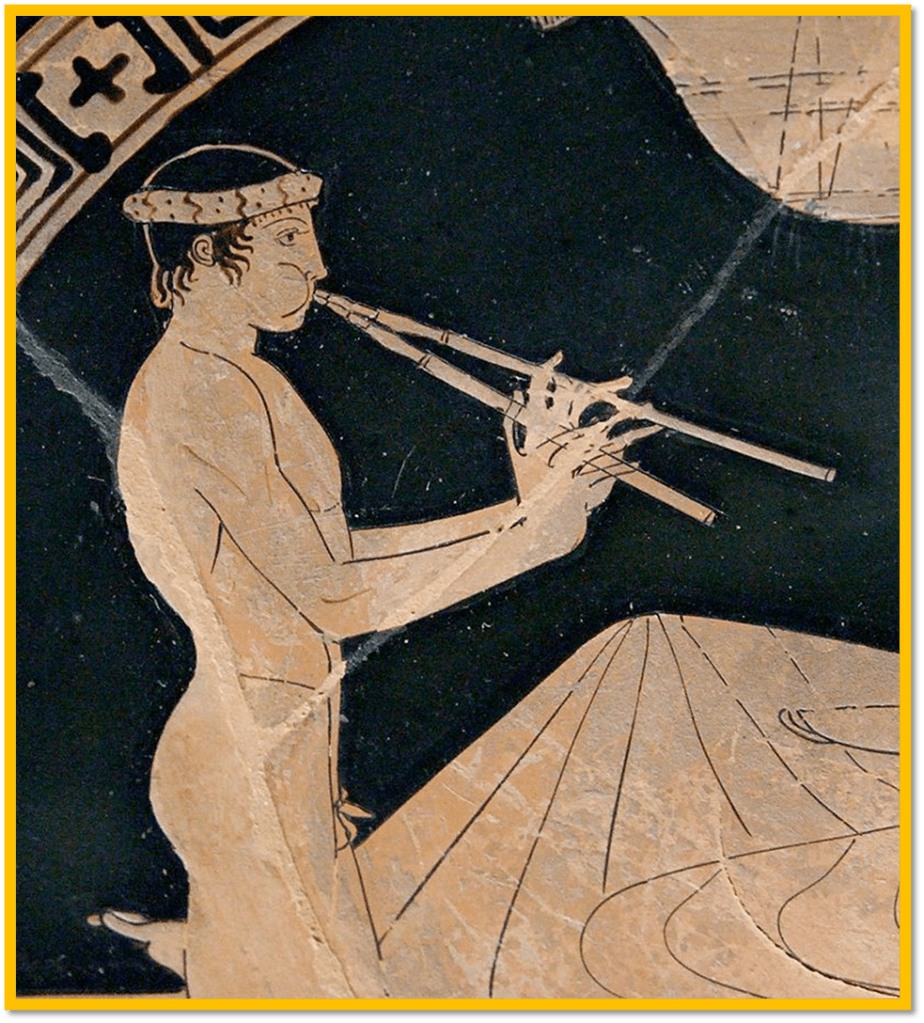

Fox makes much of the ‘his wisecracking friend’ of Gelon (the straight man in their double act) like most other newspaper critics. However, it may be because newspaper critics try to avoid spoilers that Fox does not exactly describe the tragic content, especially when the play concerns the production of two of the greatest tragedies in the Western canon, These are Medea and The Trojan Women and the novel even includes a vignette from the life of their author, Euripides, amidst a symposium (of the Attic variety, organised by his slave attendant. Both of these tragedies both have tragic heroes who are women, although played by men in the Greek theatre of course, and that is relevant, I think, to the deepest serious level of this book that underlies its emotional engagements, though engagements that sometimes, as it were, flow too fast, as well as deep, in an undercurrent, to be felt whilst definitely being there. They might be epiphenomenal to the main themes but my sense is that they are not and are central to the novel’s conception of the emotional life of Greece and Magna Graecia.

But let’s deal first with the issues in descending layer of obviousness from those on the surface of the text. First, the themes that form the nature of its comedy. As with Fox, Bonet (who sums the novel as one ‘to be gulped down in the same way as Lampo giddily does his jugs of wine’) relishes most, as those words convey, the character comedy supplied by the narrator’s ‘character’ role as Lampo, an illiterate unemployed potter. Lampo is the kind of narrator that veers across the full range between reliability and unreliability in that role, even down to lying in both obviously motivated and less self-conscious ways. The latter I’d suggest are a kind of imaginative invention where Lampo doesn’t know or acknowledge the depth of the source of something that has made him feel very intensely. Bonet is right however to say: ‘This voice is also a vehicle for brilliant characterisation: it is as though Lampo is sitting beside you, talking your ear off’.[3]

I have hinted that for me Lampo goes deeper but even comic effect, which I get too, can be a matter of taste, or of the critic manifesting ‘taste’ as a skill they possess. It is the latter trait of the ‘critic’ that I suspect in A.K. Blakemore’s view that there is something off-key in Lampo, whose language is seen as effective in conveying ‘gallows humour’ but not in anything that might be more serious, where to Blakemore he is and sounds ‘sentimental’. I will quote what Blakemore says, for my difference in taste, if that’s what it is, to theirs is crucial to me seeing those deeper undercurrents in Lampo in particularly those ones never shared explicitly.

The novel is told exclusively from Lampo’s perspective, and while he makes for an amiable narrator, there are some points where his perspective jars. I liked him as a disinterested militiaman (he observes that killing “is a good buzz”, if “weird”), but found him – and the novel overall – much less convincing once the gallows humour of the opening chapters gives way to the aphoristic sentimentality of the later ones.

Blakemore quotes one instance of the supposed ‘aphoristic sentimentality’ that, in their words, ‘packed about as much emotional and intellectual heft as a novelty fridge magnet’.[4] No fridge magnets for this person of taste, heh! But I don’t get ‘sentimentality’ in the novel’s progression, even in the main heterosexual romance plot of Lampo’s love, and determination to buy, and free, the slave, Lyra of Lydia, who works at the ‘public house’ Lampo and Gelon oft attend. For Blakemore this trait of the mid and latter parts of the novel attest, like the novel’s brevity (though it is not much different from the length of many of this year’s Booker longlist), to its failure to achieve ‘much meaningful engagement with its themes of ‘poverty, incarceration and exploitation’. These are, in fact, not deeper themes of this novel , in my view, but givens of the historical setting. However, one element of the novel’s comedy everyone comments on, is the metamorphosis of the Sicilian cast, at least that part who are NOT the Syracusan aristocracy, is that they speak like Irishmen (it is men only I think). Fox says it best, giving a cracking example of the dialect’s grammar, in saying that Lampo:

narrates the novel in a distinctly un-Sicilian voice. “Would you be knowing any passages?” he demands of a near-dead Athenian, seeking an actor to play Jason.[5]

I rather like the litotes of ‘distinctly un-Sicilian’. Blakemore makes the point more ponderously:

Lennon’s most significant innovation is introducing a modern Irish vernacular to his classical setting, but if you’re fine with a BCE Sicilian shop owner saying, “Sure, time flies is what it does” – and, let’s face it, who but the most tiresome of historical purists wouldn’t be? – you’ll stop noticing after a few chapters.

But I don’t agree, you stop noticing, as if it were an aberration of the mixed culture Irish-Libyan novelist. For him voice and identity matter, and yet, strangely enough, Blakemore is the only one of the critics I read to notice that the Irish name of the central character Tuireann, a collector of antiquities, a merchant (but definitely not of slaves) and a kind of magician, as well as ‘producer’ (providing the finances) of the plays of which Gelon and Lampo are the ‘directors. The name of this strange character seemed out of place and connects the novel to one of its trans-historical themes. And it is Blakemore, paradoxically, who nails the reason why:

The friends’ mysterious benefactor “from the Tin Islands” named Tuireann (an Irish variant of “Taranis”, the ancient pan-Celtic thunder god) provides a contextualising link between the Hellenic and Gaelic narrative traditions that Lennon clearly holds in equal reverence.[6]

So why Taranis? And more particularly why the Irish form Tuireann, which some accounts (if not Wikipedia) see as variants. That an Irish mythical being is evoked feels pertinent, but in the same way the comedy of the novel’s banter in Irish dialect relates to deeper and more serious themes -strangely and queerly. The Tin islands that he hails from are another mystery, with a Bronze-Age Greek provenance. But, although there are many candidates for the islands referred to by the Greeks, are they, or do they include Ireland? The mining of tin in itself does not help identify Ireland, for although the evidence of copper mining in Ireland goes back as far as between 3000-2000 BCE, the Copper Age, there is little or agreement amongst scholars (see the 1994 paper by P. Budd, D. Gale, R.A.F. Ixer & R.G. Thomas) that Irish Bronze-smelters (Bronze is usually an amalgam of copper with tin) in the Bronze Age, the age of human technological development that succeeded the ‘Copper Age’ because of the greater durability of the metal, about how, or if, tin was sourced in Ireland. Irish smelters were unlikely to have used Irish tin deposits, for they were not found sufficiently in identifiable forms Budd and his colleagues say. Nevertheless Irish bronze existed of high quality and the debate seems from popular accounts to continue.

However, Tuireann, is a complicated figure and Irish only by association and perhaps through lots of false leads. He seems to represent something uncategorisable, perhaps slightly vampiric, certainly ghostly. Lampo can’t ’place his age. The skin on the face is pale, barely lined and the hair is dark, long and glossy, but there’s something old about the eyes, the neck’. He is in love with war and its memorials and praises the boys for the ‘addition of fresh blood’ on the Attic amour they sell, though the blood wasn’t fresh – far from it. [7]

The defeat of the Athenians at Syracuse romanticised.

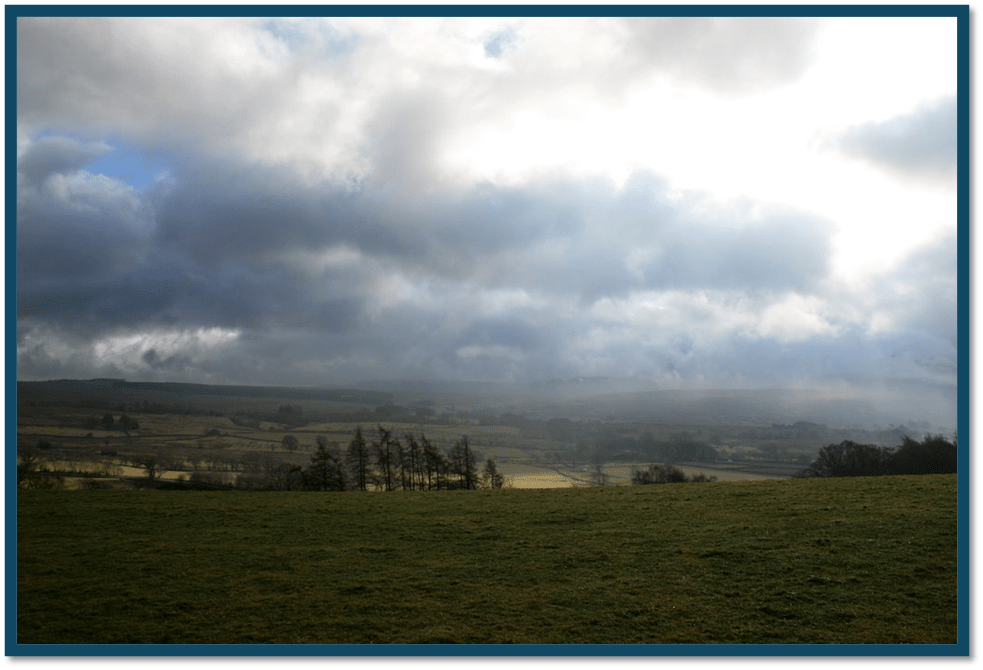

His association to ‘thunder’ is more with ‘rain’. He love of metal, especially silver is ubiquitous in his appearances. He himself won’t place the ‘tin islands’ but says they are near Atlantis, perhaps (I suppose) that means, possibly imaginary, but they are characterised by ‘rain’. He speaks in riddles

“… That rain outside, you think it’s bad?”

“It’s pissing.”

“Picture a land where it always rains. Storms like this every day. That’s the tin islands, though it’s greener than anything you can imagine too. You drop a stone in the ground, and it will grow into a tree in the land I come from.”[8]

Rain and green in Ireland

And the clinching moment for me is in a later conversation when a place ‘rain and woods’ is evoked again but not identified with the tin islands specifically, but a place as evocative of tragic war as the Troy of Euripides’ The Trojan Women, that might as elsewhere be everywhere, a constant counterfactual repeated in different ‘worlds’

…. “Once, something very much like that happened.”

“War, sure, it happens all the time.”

He smiles sadly and nods..

“Yes, it does. It truly does. But this happened in another world entirely. Not the dusty plains of Ilium, nor Syracuse. No, it was in a land of rain and woods, a green-growing world, but yet it happened in exactly the same way. The hearts of men are alike wherever you go. The rest is scenery’.[9]

This green woody place may be Ireland and the tragic wars those of Ireland but Tuireann’s point is that his godlike thunder strikes everywhere, its spoils similar irrespective of ‘side’ (hence he collects the detritus from all sides in any war). If Lennon remember, through the vague and inconsistent pointers in Tuireann, a home in Ireland, perhaps he also remembers Libya in his family’s stories of desperate war-torn pasts. I think the identity of the suffering involved in conflict, regardless of each of the number of contending sides in the conflicts referenced, is made deliberately generalised to every place at every time.

The product of conflict is underlying tragedy whatever its place or time. And this novel is set in the aftermath of a specific conflict whose sequelae are hard to decipher set of signals under a tragic story which must be turned into art – both tragic and comic art. I think this is why the novel depends on two directors of the business of the plot focusing on the production of plays, or in Gelon’s terms:’ “Full production”, he says, voice shaking, “with a chorus and music and masks. Costumes too, a proper play. Like they’d do in Athens” ‘. Lampo ought to be insensitive to this art theme if many critics are correct about him. He is ‘loud, crude, and often inappropriate’ according to Bonet because he refers to the play as ‘Chorus, masks and shit!’ shortly after Gelon’s version. Varieties of such judgements appear everywhere in the critics. But even from the first, it is clear that art is not only comprehensible in terms understood by Gelon, and that for Lampo those terms go deeper than those things that he knows on the surface. Just before he says the words cited by Bonet he speaks others about what might lay below a play and its trappings of artifice. Lampo imagines something in art that awakes those long sleeping, and not just the ‘hundreds’ of Athenians in a pit at which he stands on the edge, saying: “Wake up, Athenians. Wake up!”. Those Athenians become something more, something more generalisable in humanity across space and time as Tuireann imagines them, hard to rouse but capable of life, though not showing it just now. His word depend on belief:

That somewhere in the black they exist, but where and who, and what are they thinking, feeling? It makes my head spin and gives a kind of swirling beauty to the dark.

This is one layer of the deeper level of the play and I do not consider it sentimental as Blakemore does. At times, it seems a contribution to philosophy, mystical perhaps, that affirms and states a value-system for understanding life in ways not usual to the majority in all social settings and times. The value of life is a theme partly played out in references to the lost (Gelon’s wife and child) but also in reference to commodity capitalism as a means of evaluating life in mercenary ways in the theme of slavery and trade. Tuireann is able to buy and sell persons but not in the form of the mass trade of slavery. The value of a life is explored in the symbolic form of children. It is so, in projection, explored in Medea’s murder of her children in her play (her children are called ‘kids’ like the ’kids’ Gelon recruits to staff his play’s execution). The latter ‘kids’ hum the value of life to the words of the play.[10] It is treated again in the story of Astyanax in The Trojan Women. It is treated too in the value Tuireann gives to strange remembrances of art and mortality in his role as a strange collector of things, even a rather sordid rope related to a man’s story of his escape death. And most prominently it is treated in the many reflections on the price or cost of Lyra, the Lydian slave that Lampo effects to love.

At one point as the lovers converse, the possible sources of the value of Lyra shift. Was she of value because she was once an ‘aristo’ (an aristocrat before she was seized in war – like Briseis in The Iliad whom Achilles desired, putting at jeopardy everything he valued), or because she was ‘rich’ (a thing she disdains but then the rich can afford to do so Lampo thinks) or because of the knowledge she has learned and can teach Lampo.[11] In the end her value is that of the highest bidder – and by the time Lampo ‘earns’ three hundred drachmas quoted by her owner, she has been sold elsewhere at 700 drachmas.

At the level of the theme of how we value ‘life’, the ‘scenery’ of the novel is another artifice, like the scenery in Alekto’s theatrical workshop of masks and sets, although one that does not yet possess the artifice of the machine for suggesting divine intervention. Strictly speaking one of these is required in Medea, where Medea is carried away on a divine chariot to Athens from Thebes. The machine was named the ‘deus ex machina’ (or ἀπὸ μηχανῆς θεός , apò mēkhanês theós in the original Greek). The point about this theatrical artifice is made at least twice and perhaps that sets the thinking about the likelihood of the divine event occurring in the novel, although Alekto, the theatrical objects manufacturer and seller, once seems to mime such an event.[12] Yet the unconscious is very like the divine Freud thought, as in the moment when Gelon and Lampo pour out a libation, of the ‘most expensive wine’ from the shop as Lampo mournfully notices, to the ‘Gods’ in the hope of a good play. The circumstances of the libation certainly carry something like divine experience into Lampo’s inner being, but it is not derived from the Gods but of the feel of human contact and warmth, for when Gelon asks Lampo ‘to take his hand’, he says: ‘I don’t joke, or curse him for wasting the booze. There’s something too eerie about the feel of this place right now; I want the warmth of a friend’s hand, and I grip it’.[13]

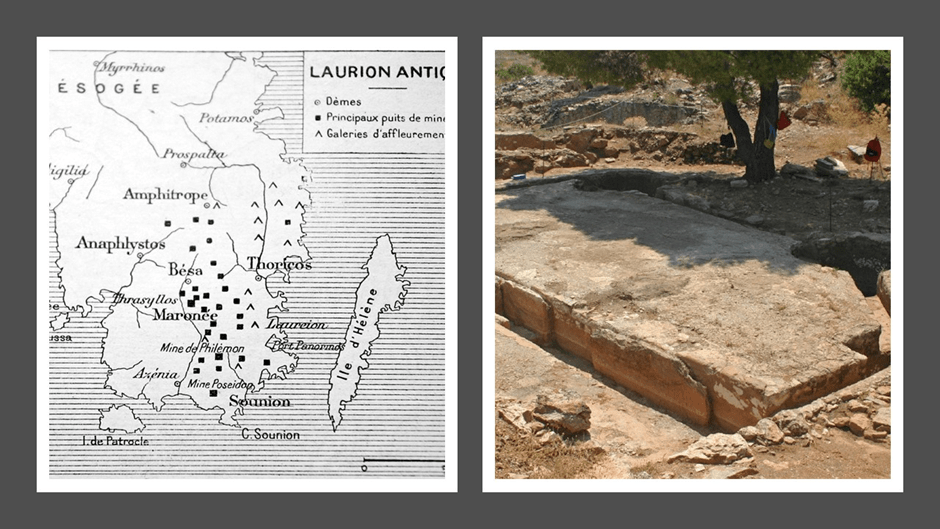

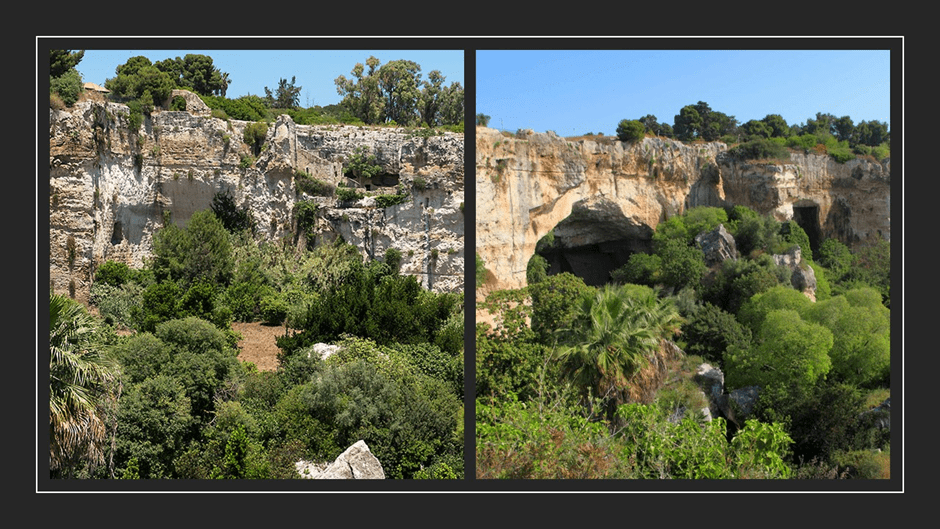

I will return to the significance I see in that taking the ‘pressure of a hand’ (as Tennyson articulated a similar hand grasp in his Lyric CXVII, a lyric that takes up the theme of the grasped hand from Lyric VII of In Memoriam) later when I trace some of the undercurrents to a suppressed counterfactual story of queer love unexplored on the surface of the novel. First though but I want first to show how scenery evokes emotional realities, especially in dealings with deep and dark depressions – in physical terms ‘pits’ and quarries. These pits existed in Syracuse, and still do, although the novel adds to their meaning by anachronistic naming. For instance, the play is performed in Laurium (variously known as Laurion or Lavrion), the names of the silver mines outside Athens on which Greek naval and imperial wealth was based.[14] These names further confuse space and time (the Laurium caves being more ancient) in the novel. Here is a taste of the Attic place:

That place has not the grandeur, nor the closely observed features in the description of the real Syracusan quarries, with their vertical faces and insert caves for hiding (and loving) in that appear throughout in Glorious Exploits.

Pits seem to me in this novel the time-space (for ‘the pits’ is a contemporary name, by derivation, for the worst kind of mental depression or mental response). And this chimes with the depressions associated with Gelon and attributed in him to the loss of his wife and child – visions of whom Tuireann offers him in the place of a ‘’god’ – in which a deeper view of human mortality and mutability is explored. As Lampo says, very early in the novel, that though the Syracusans regret using their abandoned quarries as a prison, he likes ‘the pits. It reminds us that all things must change’. That glib statement over, Lampo’s reflections turn into a vision of a beauteous vision of a band of men brought low:

I recall the Athenians as they were a year ago; their amour flashing like waves when the moon is upon them their war cries that kept you up at night, and set the dogs howling, and those ships, hundreds of ships gliding around our island, magnificent sharks ready to feast.[15]

The dangerous beauty of men is set against how they contrastingly look in the ‘pits’ ( ‘a ready-made prison, walls of rock’) wasted and dying.[16] The recall is of the Homeric fleet at Troy with the modern addition of the desirous thrill of men who keep you up and invade at night. It is too lyrical to be merely fear we, or Lampo, might be actually feeling here. I will explore this further soon as promised earlier but there are other metaphoric indicators of the sub-story, we also need, related to being raised or resurrected from pits and ‘ruins’ equally. Most critics do tell us, without convincing us they feel it successfully dome, that Glorious Exploits is essentially about the resurrecting quality of what some call ‘stories’, or other ‘art’ more generally (as indeed the book does). Blakemore says from the start that: ‘Glorious Exploits, is very much a story about the power of stories’. Yet he doubts its success:

Although Lampo and Gelon’s perspective on their actions alters as their relationships with the Athenians deepen, Lennon’s reverence for their theatrical undertaking – for art, for stories, for this business we call show – glosses somewhat over the moral queasiness of their methods. To me, the novel often contradicted its own suggestion that tragedies ought to teach us there is “dignity even in the worst that could happen under the sky”, apparently unintentionally. (my italics)[17]

This feels to me not to try hard enough to read what is there in the novel, rather than what Blakemore would like to be there. If I am right, art is ambiguous anyway. It is a thing made up of artifices – mere ‘scenery’, ‘masks’, ‘costumes’ and narrative decoration, but it exists too at a deeper level than ‘this business we call show’. It exists at the level where its embodiment turns artifice and show into something living and dying – the stuff in ‘life’ we value and those in dying that we ought to value. See this description of Lampo looking at the ‘assortment’ of theatrical goods they take from Alekto, a friend of his mother’s who loves him:

… lying there empty. Hollow, and tomorrow they’ll join with the Athenians for a brief moment and fizz with life. Nothing here is alive yet, but it throbs with expectation; the robes, and crowns, twitching almost like spring flowers just before the bees rock up.[18]

The informal linguistic phrase ‘rock up’ is part of the life given to mere dead things here, tying itself to the metaphors of ‘spring’ that have sung the mysteries of life in death since the dawn of Christian, and indeed pre-Christian, art. Hence Blakemore is wrong to see the fault lines in Gelon and Lampo as errors in a novelist’s method – they are as essential to art as the faults of Rainer Werner Fassbinder were to Fear Eats The Soul. We see all this happening when the Athenians dress for action and the scenery is revived: ‘it strikes me they’ve returned to a second childhood’:

The suffering has stripped away the years in the way carpenters can uncover the youth of a tree by scraping the plane against the old bark. Yes, I think they’ve found a sort of innocence in their ruin.[19]

All of this is rehearsed again, somewhat in opposed direction, when Lampo and Gelon seek though the ruined lives,ruin brought on by the dangers they courted by raising the hopes of the Athenians against likelihood of success, to find very little life.[20] Likewise, though, gold coin seems to promise new life but that promise is an illusion.[21] And yet, in the attempt to redeem the lives of Athenians (and one, Paches, in particular) Lampo seems to fighting to redeem the whole world through the spiral-form of a narrative that encounters lapse as much as it encounters forward progression. The pits become an emblem of a world requiring redemption:. The art here is a rough music played by Lampo, badly, on an aulos:

But it clashes with the scurrying of the rats, their awful screeching, and in my mind, those rats aren’t just rats, they’re everything in the world that’s broken. They’re things falling apart, and the part of you that wants them to. …Those rats are the worst of things under an indifferent sky, but the sound coming from the aulos, frail as it might be in comparison, well, that’s us building shit, and singing songs, and cooking food, …[22]

The mood in that passage, which references Yeats’ The Second Coming of course, dips after the words I quote but that’s the point. Euripides’ servant, Amphitryon (the name of an imperfect man who tried to act like a God in mythology), says of his master : ‘was ever in love with misfortune and believed the world a wounded thing that can only be healed by story’.[23]

It ‘can only be healed’ that way, but that does not mean it yet is, as Killian Fox rightly says (in his words). He says that the novel ‘stops well short of suggesting that stories have the power to heal the world, but – just sometimes – they can make a difference to individual lives’.[24] The point is to keep telling the stories until imperfect listeners understand them. Fox is much nearer to seeing this theme but does not suggest how subterranean it this, if less so than its connection to the way war in the history of Ireland and Libya would also support this theme.

However, for me (and it matters to me, at the least), this novel has an important contribution to the aesthetics and ethics of queer history and art history. Whilst all of the reviews are aware that it Lampo’s fascination with saving the character of Paches, the Athenian prisoner (and player of the roles of Jason and Helen of Troy in Medea and The Trojan Women respectively, Lampo thought him a fine Cassandra for the latter in fact) that saves his character from crudity. Whilst some of these critics overstate the crudity of Lampo at the beginning, I see their point. Yet none consider the relation to Paches as an act and process of love rivaling his love of Lyra the Lydian. And few see the relationship between Lampo and Gelon as other than just Irish teen mates.

Yet from the beginning Lampo’s relationship to Gelon is one of homage to beauty, if at first it is in the more acceptable masculine terms of being ‘shocking handsome’,: ‘Here’s Gelon’, ‘godlike, broken Gelon. Look and remember beauty isn’t all’.[25] Lampo may moralise Gelon for still suffering though being beautiful, whilst he laughs on and is less than beautiful as we shall learn Lyra too is flawed in beauty. You may remember the way that Lampo feels the religious ritual effect of a libation in grasping and gripping the power in holding Gelon’s hand.[26] From the beginning though Lampo speaks of Gelon’s laugh as a ‘soft and delicate thing’, uses the masculine word ‘handsome’ to describe him but sees his eyes as ‘the colour of the shallow sea when the sun shines through it’ rather than being ‘shit-brown’ like his.[27] This is heightened language about the other in the male if nothing else. And a drama that undermines almost the main story is the growing awareness in Lampo that his role and special evaluation in Gelon’s eyes is being won from him by the young kid, Dares. Dares shows his readiness to become loyal to Gelon, and his second in all things, from his introduction.[28]

None of this is to claim that the novel dramatises suppressed queer masculinity, for it is clear that in the world of the novel to love a man is not inconsistent with loving a woman or one’s own child, or wider family. There is a beautiful moment at the end when Lampo accepts that Gelon must leave Lampo because now attached to Dares, and visiting him for dinner at Dares’ mother’s home.[29] Eventually Dares ‘nods at every word’ of Gelon, and Lampo knows his influence with Gelon is all the less, ‘whether I like it or not’. I infer he doesn’t like it.[30] Dares draws the laughter, that Lampo found ‘soft and delicate’ but heard rarely, out of Gelon and hearing and seeing that ‘jolts’ Lampo ‘out of (his) reverie’ about Lyra. There is love and jealousy in this. By the time of the theatre night, Lampo can only record: ‘Dares yapping to Gelon as Gelon listens with a contented grin, …’.[31] When Gelon is laid low in battle by the Herculean but stupid Biton, Dares is the ‘kid’ that was crying, and simultaneously ‘scratching at Biton.[32]

As Dares captures the heart of Gelon under the narrative surface, so Paches becomes the substitute for Gelon. Paches is clearly in love with a comrade hoplite, who Biton kills finding them in each others’ arms, and would kill Paches too were it not for Lampo’s quick wit in saving him from the drink-led Biton. Later Paches see his past lover’s corpse and ‘drops to the ground and starts crying, kissing the body and whispering to it’.[33] And from then Lampo keeps on saving Paches (ensuring major roles in the plays to maximize his food ration for instance) , or attempting to, though Paches reverses roles when Lampo is hurt. The attempt to save Paches from Laurium and not knowing whether in fact he has done so is the narrative highlight of the novel. And Paches decision to ensure Euripides knows of Lampo’s role in honouring the poet-dramatist is equally beautiful. The thing we know best about Paches, is his green eyes, eyes that constantly attract Lampo and identify the man he wants, however hidden in a quarry cave among ‘fuckloads of blues, browns, and even greys’: ‘Until one pair is. Slits of green like blades of grass glinting in the rain’.[34] Is the reference here to Walt Whitman’s Leaves Of Grass, and the ‘manly love of comrades’ or to Ireland. Who knows? As Lampo feeds him early in the novel, Paches ‘eyes gain light’.[35] Those eyes are the first things he sees when Paches nurses Lampo well.[36] But most of all, those green eyes ate transsexual. They gain him the part of the uxorious Jason in Medea, but when Paches plays the seductive Helen, as he puts on her mask, he:

… disappears. The only trace is the green eyes peering out through the holes, but even they are altered, somehow feminine.[37]

I have cited already Lampo’s queer dreams of the predatory shark-like Athenians, men of the night. [38] Lampo finds in Paches eyes ‘strange hope’, but the hope is found in the quarry, ‘a strange place, and a man is not himself in here’. If he is not a man’ what is he?[39] Paches is a man who can be a woman, and not just by donning one of Gelon’s home-made wigs, and be the most beautiful woman of Greek mythic history. Lampo is not so attracted to feminised ‘aristos’ but he notices them: ‘more like a girl than a fella’. They were in Lampo’s view ‘only here for the bit of rough’. [40] Numa, the Athenian past actor turns from man to girl and makes Lampo hate Jason for his masculine perfidy to woman.[41]

This blending of the masculine and feminine is sometimes a sign of something distrustful or novel like the new servers at the refurbished public house paid for by Lyra’s slave-sale at the highest price: ‘pale and pretty as a girl’, but he winks at the ‘young fella’ nevertheless.[42] There is something worldly-wise about this, the rough who might be up for it, although the feminised ‘aristo’ becomes an implacable enemy, it is for different reasons. In my view, I think this kind of play with binaries is suggestive entirely of the turning of sexual identity and choice of sexual object into a thing of play – a cover on the surface but full of potential underneath. That Lennon keeps it so does not suggest his subject is uneasily repressed sexuality but that it honours a full comprehensive sexual range of response that could come out if it had the energy to fight expectations. Gelon seriously misses his wife and son but Tuireann exorcises them in offering him the vision of their shades. I think, though Gelon dies, his life ends with Dares and though that is not commented upon, Dares’ mother welcomes him into the home.

And all this subterranean human under the raucous humour is I think why I love the novel, even if I miss Ferdia Lennon’s intentions entirely. Anyway, I hope you read it and get what you need from it. Conversation welcome!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Anna Bonet (2024) ‘Review: This is the debut novelist to watch’ in the i newspaper (January 11, 2024, 10:18 am (Updated 3:20 pm)) Available at: https://inews.co.uk/culture/books/glorious-exploits-ferdia-lennon-review-2840184

[2] Killian Fox (2024) ‘Review – uproarious am-dram in ancient Sicily’ in The Observer (Sun 21 Jan 2024 13.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/jan/21/glorious-exploits-by-ferdia-lennon-review-uproarious-am-dram-in-ancient-sicily

[3] Bonet, op.cit.

[4] AK Blakemore (2024) ‘Review – classical tragedy as a Celtic caper’ in The Guardian (Sat 6 Jan 2024 07.30 GMT) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/jan/06/glorious-exploits-by-ferdia-lennon-review-classical-tragedy-as-a-celtic-caper

[5] Fox, op.cit.

[6] Blakemore, op.cit.

[7] Fredia Lennon (2024:79) Glorious Exploits Fig Tree Books, Penguin

[8] Ibid: 81

[9] Ibid: 217

[10] Ibid: 116f.

[11] Read ibid: 126ff.

[12] See ibid: 174. The way the directors overcome the absence of a deus ex machina is explained in ibid: 196.

[13] Ibid: 175

[14] See ibid: 4, 29 for name.

[15] Ibid: 6

[16] Ibid: 226

[17] Blakemore, op.cit

[18] Ferdia Lennon, op.cit: 165

[19] Ibid: 181

[20] Ibid: 209

[21] Ibid: 258

[22] Ibid: 239

[23] Ibid: 276. The last words of the novel.

[24] Fox op.it.

[25] Ibid: 37

[26] Ibid: 175

[27] Ibid: 3

[28] Ibid: 38f.

[29] Ibid: 259

[30] Ibid: 107

[31] Ibid: 162

[32] Ibid: 204

[33] Ibid: 13

[34] Ibid: 229

[35] Ibid: 30

[36] Ibid: 205

[37] Ibid: 181

[38] Ibid: 6

[39] Ibid: 10

[40] Ibid: 23

[41] Ibid: 33f.

[42] Ibid: 260