A reflection on the Lavery On Location exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art, Scotland in Edinburgh, visited on Wednesday 14th August 2024 using reference to its catalogue: Brendan Rooney [2023] (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland.

This is a sequel to a record of the day in general which can be read at this link.

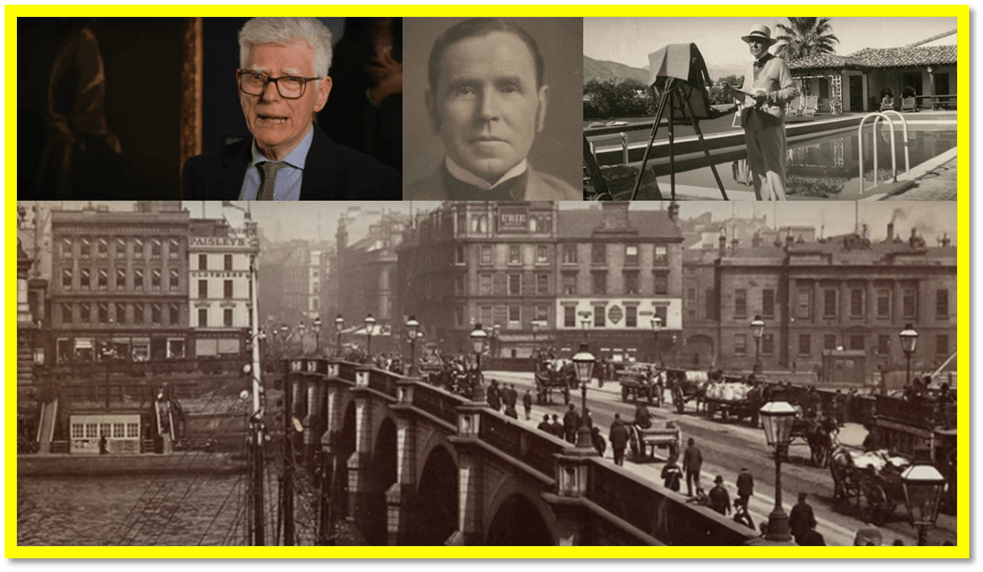

Had anyone predicted that I would visit any exhibition focused on the life-work of Sir John Lavery RA RSA RHA (20 March 1856 – 10 January 1941), I would have disputed the prediction. This is probably because Lavery’s reputation as a man enamoured of the rich and famous as subjects and as hosts with whom he might stay whilst painting, even though he may ‘have come from nothing’, as the art historian Kenneth McConkey says in the film that is offered as prefatory to this exhibition (an also available online use this link). This kind of self-made man from the cusp of the nineteenth-and-twentieth centuries Is hardly the kind of figure I am habituated to like; to me he fitted the ‘type’ of men who climbed a slippery pole to prove they could grease it further to stop successors rising with him, becoming bourgeois salesmen of their art and fostering links to monied and landed aristocracies. Lavery had it seemed many characteristics of such men – relishing and naturalising his right to a place at the top, it was appropriate also to idealise those who stayed where they were. If this was how Lavery worked, and I in my prejudice thought it was, it explained how he rendered the poor and marginalised, in relation to the values of a white imperialist power like Britain as satisfied but naturally minor figures romanticized and, in the case of Muslim Africans, exoticised in dress and behaviour.

And there is that in him. There are three instances from the exhibition I found intriguing, both having a negative aspect in terms of the artist’s grasp of the poverty and marginality to the bases of power and opportunity of others, once he left behind those circumstances of his life in childhood and youth: according to stories he told a reporter in the 1920s, stealing bits of bread that had been thrown out to birds by scaring the pigeons on Glasgow Green away to ‘dine on their crumbs’, for instance, or feeling so trapped and confined by the power of others that he ran away from what stability he had been offered only to discover his talent in drawing caricatures. We almost hear the self-made man telling his romanticized story here in ways that increased his self-regard and his belief that addressing poverty was an issue for individuals making something of themselves.[1] He must have felt that what he had achieved was not bad for a boy orphaned at the age 3 in Belfast and making his own way (and sometimes not) from the age of 10 in Saltcoats, Ayrshire. In the art this aspect of the artist’s self-making is revealed in these three concerns in the treatment of his subject-matter in the art itself.

- The treatment of his past as a displaced child in Ireland and its links to the national identity and connection claimed by Lavery;

- The treatment of the appropriate perspective and point of view of the artist upon events, people and scenes, and;

- The treatment of the means by which people of other races or identities are ‘othered’ from the presumptive type of the artist and the implied identity of his art’s viewers.

I will deal with each concern one by one, although in doing so, I will insist not only on the evidence that the framing ideology of Lavery’s art is problematic but also with the nuance in that art that modifies or even challenges directly the implied judgement of him.

Treatment of his past as a displaced child in Ireland and its links to the national identity and connection claimed by Lavery

There is a potted biography in the video produced y the National Galleries Of Scotland to which I have already referred, which is the story developed by Kenneth McConkey in his catalogue chapter entitled ‘Lavery’s moderrnté’. Some of the material from the film tells part of the story and above we see McConkey next to an early picture of the artist and then another showing him painting at the poolside of his Moroccan villa, Dar-el-Midfah, the ‘House of the Cannon’ overlooking the Straits of Gibraltar and obviously which had a rusty cannon in its garden, a reminder of the strategic importance of the Straits of Gibraltar, whomever the European enemy. The wealth that sustained Lavery was that of rich capitalist patrons, essentially, from the first, those in Glasgow including William Burrell. The scene of Glasgow business on the Clyde and across its bridges tells that tale in part. We should not forget that he was known as one of the ‘Glasgow Boys’, a phrase that hardly captures the establishment grandeur they aspired to enter.

McConkey in the film uses that unfortunate phrase of Lavery that he came from nothing’, that gives the game away for more art historians than he, that they buy into bourgeois and / or aristocratic notions (the two allied to share power in the period of Lavery’s life up to the First World War) notions of the hierarchies of human vale. It doesn’t help when he glosses it, immediately afterward, as meaning Lavery had ‘no money, no background’ on which to depend – only the promise that his talent would produce sellable pictures. In his catalogue essay, the expression is more sober, as he tells us that ‘money, for him, had always been a pressing issue’.

Starting out, Lavery had none. By the time of his death there was the equivalent of over £4 million in present day terms on deposit and a decent house in South Kensington, and for most of his life he was comfortably off, but never more than that.[2]

There are good reasons then that Lavery became an artist ready to follow the money and not an innovator like others he knew such as Jack Yeats, and Henry Matisse (who though badly of Lavery’s work as you might guess when invited to visit Lavery in Dar-el-Midfah).[3] Though dubbed an ‘Irish Impressionist’ in this shows, few works seem to fit an impressionist category, except in their interest in light. His work is a compromise of styles and models in the art of his time, his nearest influence being Jules Bastien-Lepage, a man who challenged other Salon artists by aiming for a naturalist method based on the imitation of everyday reality, rather than the classical subject matter of that part of the French Salon represented by, for instance, Bouguereau. As his Wikipedia page says in a good summary Bastien-Lepage was not seen as an enemy of Impressionist innovation but a moderator of their principles in the interests of an art that could be sold to bourgeois tastes capturing the national every day.

The influential English critic Roger Fry credited the wider public’s acceptance of the Impressionists, especially Claude Monet, to Bastien-Lepage. In his 1920 Essay in Æsthetics, Fry wrote:[7]

Monet is an artist whose chief claim to recognition lies in the fact of his astonishing power of faithfully reproducing certain aspects of nature, but his really naive innocence and sincerity was taken by the public to be the most audacious humbug, and it required the teaching of men like Bastien-Lepage, who cleverly compromised between the truth and an accepted convention of what things looked like, to bring the world gradually around to admitting truths which a single walk in the country with purely unbiassed vision would have established beyond doubt.[4]

That is enough to see the main drivers of Lavery’s art. It must tell of everyday life and capture it in ways people recognize by innovating only within certain parameters and subjugating sometimes the naturalism to the sense of a narrative, or at least a theme, that allowed for bourgeois table-talk over dinner. The compromises also had an effect on his choice of national identity which, from an early time he decided would not be Irish as such but international, starting (since it was the capital of art) in France, rooting itself in Scotland(almost so predominantly that many know him as a Scottish artist) but taking in also colonial North Africa. Brendan Rooney is fascinating in his catalogue essay about Lavery feeling, with other Irish artists looking for a name that, in the words of Lavery’s friend, Thomas MacGreevey, Director of the National Gallery of Ireland ‘in their work as in their lives, have to concede a good deal to cosmopolitanism’.[5] He describes the bourgeois aspiration that grew in Lavery in Paris and Grez-sur-Loing; in the latter there was a group of artists thinking themselves following an internation model set by Bastien-Lepage.

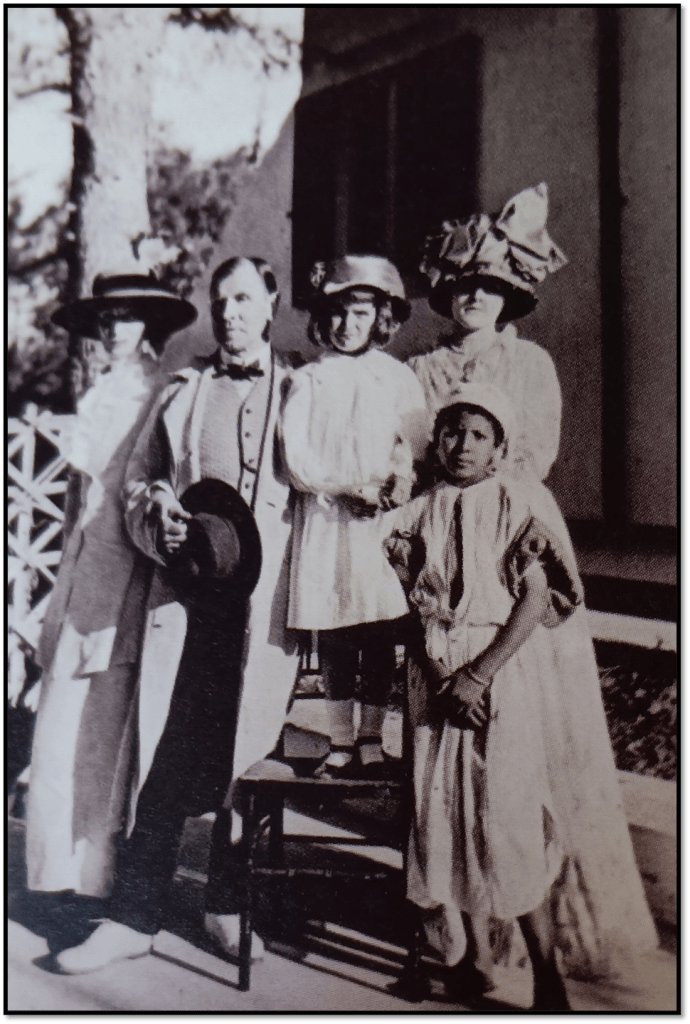

As a result there is no purely national ‘community of conviction’ to which Lavery would identify himself with as an artist. As a result his support of Irish causes was never full-blooded and without compromise to the sources of more thickly buttered bread. He accepted honours from Great Britain, Italy, Belgium and France.[6] Rooney says quite plainly that ‘his landscapes’ (and he could have added his interiors and portraits) recorded ‘ a world rarely far removed from high society’. Here was a man at home in Cannes, the Alpes Maritime and the more select hotels of Europe and North Africa’. His marriage to a much younger woman (at marriage Hazel was 29, he 53) was another way to present a man of not such much of the people but a cut definitely above that, even sporting young Moroccan servants, dressed especially in ‘traditional’ costume.

How must we think about Lavery’s determination to keep his Irish identity an option rather than as a defining characteristic. The answer must be in a nuanced way, although the paintings that most shocked me were paintings he prepared for an Irish themed exhibition that failed to take place whist being hosted by W. B. Yeats when both were nominated to the board of the National Gallery.

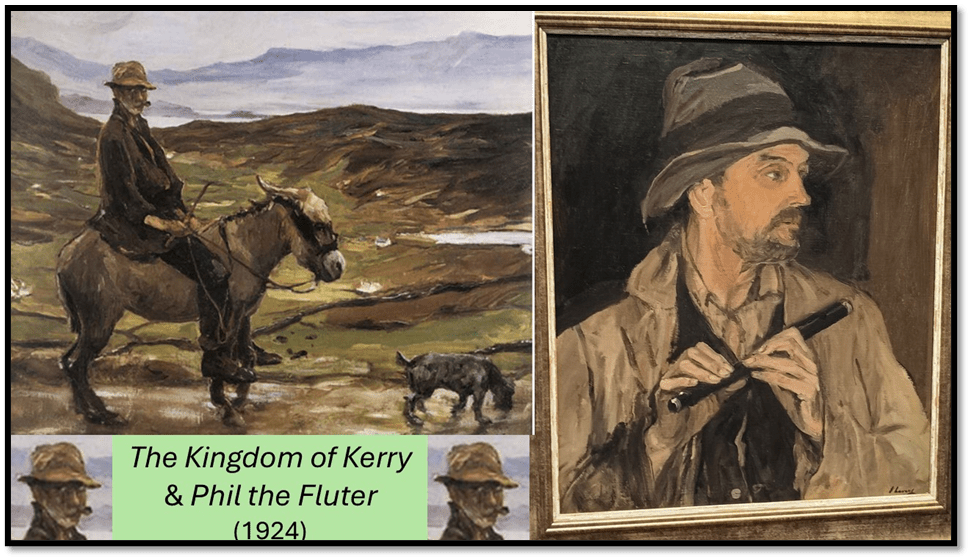

The Kingdom of Kerry may relate to the disputes between the IRA and The National Army that only continued on after the Civil War in Kerry. According to McConkey, it references the Fir Bolg who created the Irish regions but ruled Munster where County Kerry is) in two divisions. The ‘king’ of Kerry in the picture, whom McConkey refers to as an ‘aged Fir Bolg’ sat on a weary stationary donkey is clearly a satire on the pretensions of Ireland but also perhaps meant as a warm reference to a kind of naturalised Irish poverty, a man stuck in his lot and not able to move forward, a symbol everything Lavery left behind in a beloved land that he paints as ‘primitive’ and suspicious’. But lovely and unthreatening. Inevitably, this is a stereotype, and we shall see Lavery employing them continually.[7]

McConkey thinks the much better painting (both are from 1924) is also a reference to Irish folklore, though it isn’t explained how, except in the reproduction of stereotypes. The title is a reference to a scurrilous song by Percy French that takes a civilized laugh at the bizarre and laughable comic monsters of the town of ‘Ballymuck’. The ‘muck’ reference is indicative of the characterisation of a funny set of people whose meanness is only modified by deception but all at the level of a slapstick slightly sexy joke (read it at this link). Phil has the same staring gaze as the King of Kerry, as he scans the effect he has having on a break from blowing his flute. The poverty of Phil is clear, although there is a romantic cast to him. Both pictures, however good the latter (and I think it is) trade in figures that diminish the assertion of Irish identity, though in a way, I think Lavery found charming as it raised a smile at the simplicity of the people. It is a simplicity Lavery must have known to be far from the truth about the diversity of Irish character and potential.

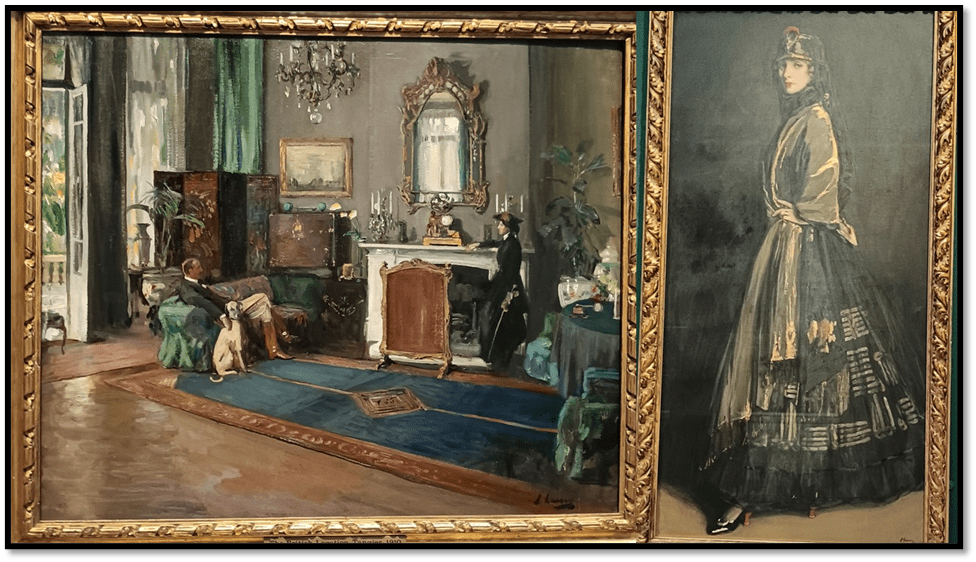

In contrast the life of the English aristocracy and bohemian ruling class in 1920, at ease in Tangiers, where Lavery first met Lady Patricia Herbert, the Countess, and more so at home, as in the case of this painting of the Van Dyck Room at Wilton House. To that Baroque home, of the Earl and Countess of Pembroke and Montgomery, Lavery was invited to complete this painting. The Scotsman called it ‘an atmospheric impression of gracious living’, but that is an understatement, for this is a room in which Lavery finds himself, as it were, hanging about as comfortably as the Van Dyck’s (painting the same family) on the walls, in the company of gracious ladies who ornament life for him.[8] These people are made for power unlike the King of Kerry and Phil, with his flute, lounging amongst a people presented essentially as a peasantry with a few odd pretensions.

How this painting works tells us something about Lavery as a person and a painter. The whole painting reflects on the Van Dycks and their relation to the Herbert family who still lived in Wilton House but importantly, it uses the fashion worn by the ladies and their modernity, for each is employed in a different and serious pursuit, rather than being openly displayed to the viewer as in the seventeenth century Van Dycks: one reads seriously with her back to the focal centre of the painted space and the room. Another may be doing the same in a seat that holds all the light from the window, with her back to the viewer and seen only as a head bent down in concentration. The third is in earnest discussion with a man at the back of the room (see the details on the right of the collage). There is no doubt that the family are being flattered as moderns as well as the people who hold together a historical tradition of landed power. The point is these English nobles wear power well in Lavery’s eyes and are not the anxious needy people displayed as the Irish.

The men of power are softened by women and made negligible, very unlike the situation in Van Dyck’s Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke and his family (1634) shown on the rear walls of the painting above (that painting shown more clearly below with its obvious distribution of men in dominant, women in decorative pose):

n the light of this pursuit of the gracious living of his patrons, whether the Glasgow industrially rich like Burrell, or the still influential aristocracy, Lavery’s Irish figures may be interpreted as loved but I find it hard not to see them too as patronised and demeaned, perhaps even made to seen nervously, and in the case of Phil the Fluter dangerously like an IRA man – the bogey of the age. But there is, I discovered great nuance sometimes in the attitude to the Irish. Here is a case in point. Below is the exquisite St. Patrick’s Purgatory of 1929. It is one of the most complex of social settings we will see in this blog and in the exhibition. Done on a ‘National Pilgrimage to Ireland’ on Station Island, sacred to St. Patrick and on Lough Derg, Lavery had to seek permission of to do the pilgrimage from the officiating clergy, seen welcoming the pilgrims. His expectation, and McConkey also thinks his desire, was to see a ritual populated by the peasants of Connemara. What he found and faithfully reproduced was that most pilgrims were well-to-do bourgeois characters, male and female. Moreover, the rule that all pilgrims become unshod and in naked feet was not relaxed for the wealthy.[9]

It takes several looks to see the complexity of foci in this painting, some done to comic effect and most to the possible dismay of the bourgeois men, at least, shown. , such as the distress of the suited gentleman who has his naked feet in mud at the centre, such that his legs buckle in his dismay in seeing his condition. I think we notice first the stereotyped peasant woman in red skirt, in part that colour attracts and the labouring people (all on the left behind here. But as the eye wander we pick up the fate of the fashionable classes, to the left of the column of St. Patrick, the bare feet of well-dressed ladies show. Further to the left tow women dressed as fashionable ‘flappers’ negotiate the cold stone, their heads bowed, not in faith, but at the horror of their exposure before the poor. Behind it all Lough Derg reflects iron skies, heavily clouded and distant mainland hills. This is a most powerful piece – but is it enough to forgive for the Kingdom of Kerry. For me it is. But the point remains, Lavery’s absorption into international high society is at the expense of his Irish identity, which he treated circumspectly as his patrons would have wanted, having been on the ‘other side’ from the Irish.

Treatment of the appropriate perspective and point of view of the artist upon events, people and scenes

We can see it in St. Patrick’s Purgatory that scenes that contain a large number of people – either assumed by the setting or painted there, are often painted by Lavery from an almost impossible perspective that looks down on them. It is even true of the Turneresque painting View of Edinburgh from the Castle (1917), where even visitors to the Castle courtyard are dwindled. This is less the case when the subjects or models are of higher class as in The Van Dyck Room, where if the gaze is slightly elevated it is only to the eye level of a man standing at an easel to paint – as we will see in other examples. It is not true of the other Irish paintings above but there elevation need not be assumed – it is there in the poverty of the subject ain contrast with the richness of the framed picture. Some attitude are natural indeed to the institutions of power and privilege. Stately homes or impressive offices are made to be looked up at by people who don’t inhabit them but are yet forced to visit them. The inhabitants of power look down. McConkey makes the point in this exhibition’ audio-visual introduction that Lavery like looking down from the roof of large buildings and attributed this to his stays in Morrocco from 1891. At that point he had no home there and met the various patrons he did, like Lady Herbert previously mentioned, in the grandest hotels meant for white colonial power visitors (the land was shared by the French and Spanish) but as a playground for wealthy Englishmen, even queer ones, who went because young men were poor and available for that reason.

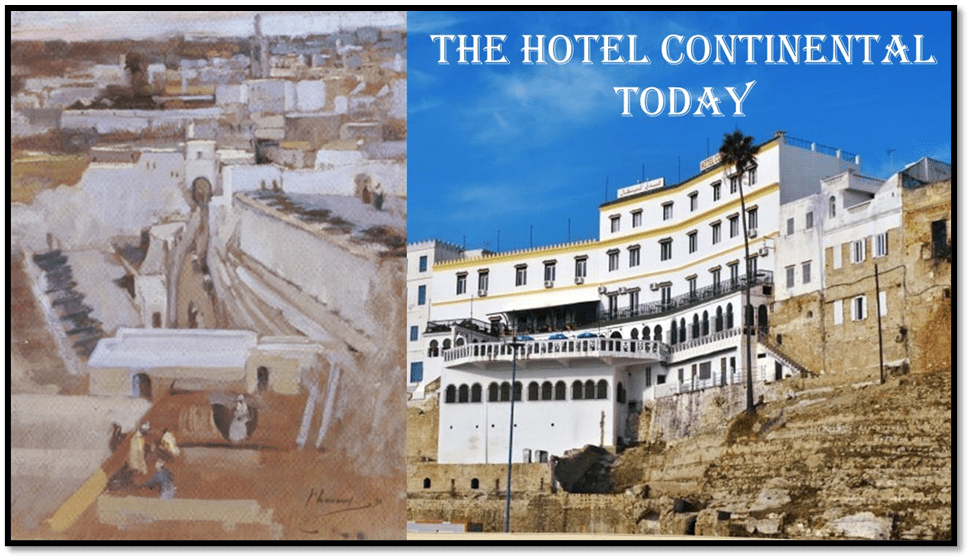

The Hotel Continental was for the very rich and even now has a high roof (see the collage below) that could be used to look down upon streets, houses and persons.

“Tangier” from the Hotel Continental of 1891is therefore for McConkey an important painting. McConkey sats that Lavery delights in the view but the artist’s terminology, as cited but not commented upon by him, shows more than delight – rather a kind of attitude of vast superiority to people, whether ‘black slaves’ (which is to him an acceptable naming, and exotically dressed local inhabitants. It seems to heighten his importance ‘more the most privileged European’ and open up an unseen exotic interior not otherwise knowable, including the look of Muslim women without the veils they wore in public. This description helps read the incredible painting as it descends into the depths of a city’s actions, the Green Mosque in its ken.

Before me rose a vista of flat white roofs, tier after tier crowding upon another, to where in the distance a graceful minaret soared into the sky. And all the roofs were absolutely alive with figures; women unveiled and robed in brilliant silks, children playing and running around them, black slaves busied in service, pets of every kind … (…) … the whole interior of Moorish life … suddenly unfolded … a vision which scarcely the most privileged European may hope to behold.[10]

It seems natural for Lavery to evaluate himself to the position of the ‘most privileged European’ he can imagine, and if he NEVER would be that person, he knew candidates for the appellation, for instance, the Minister Plenipotentiary of Great Britain, Sir Reginald Lister. Again the painting of Lister in the ‘grey drawing room of the British Legation shows equality from the more level perspective and the presence of a Lavery’s daughter, Eileen, dressed for the ’Tangiers Hunt’ imported from Britain to amuse the rural aristocracy. There is exoticism here but only in the lush carpets, though the interior setting could be in England, even the preference for an aspidistra. Who could have thought the city’s mosque was outside that open French door.[11]

We have seen already that pictures of power are softened by women, although Eileen here looks Lister’s equal, if not superior. The painting is riddled with complex attitudes to class and gender. That is why in the same collage I have placed the most famous of Lavery’s portraits of his wife, Hazel. This huge painting is formed to look down upon the viewer from an imperious height and attitude (named Hazel in Black and Gold – 1916). The aim is to create a woman whose stature (socially and physically) owes that to her husband painting her – she herself visited the portrait with Clementine Churchill, showing her proximity to friends with power.[12] There is an air of an imaginary transcontinental military queen her, the design approaching Whistler’s ‘harmonies’.

But enough of equals and superiors. My favourite painting in this show is the next one, it name Night, Tangier (1911) in the period just before the French assertion of itself across Muslim North Africa in 1912. For me this is proof enough that Lavery is nearer to Expressionism rather than Impressionism – the whole glories in significant distortions that are beautiful in design and form but also convey mood. You look at the scene as if from a haze created by the burning fires on the rooftop, from which a ghostly Arabic figure looks out to city and sea for mysterious purposes we can only guess.

The city is painted in a manner as distorted, acually just impast brush strokesand patches, and hostly as the figure overlooking and down on it. I feind this painting much more nuanced. Of course, the painter is at a higher position than this roof space as in the Hotel Contental, but we are less aware of a point of view tjhan a mood that is difficult to interpret and not one of secure power. It is a most beautiful painting that transforms Lavery’s taste for a superior viewpoint to a study of a nation in burning formation. Yet that is unusual. It works because it uses a central Arabic viewpoint not one from an identifiable Western power. It looks like it tries to become the other, rather than characterise it.

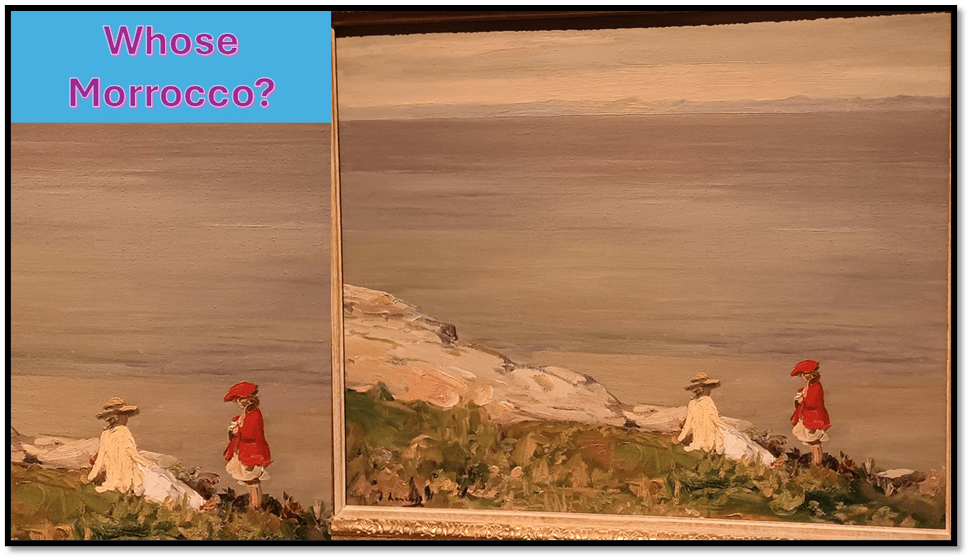

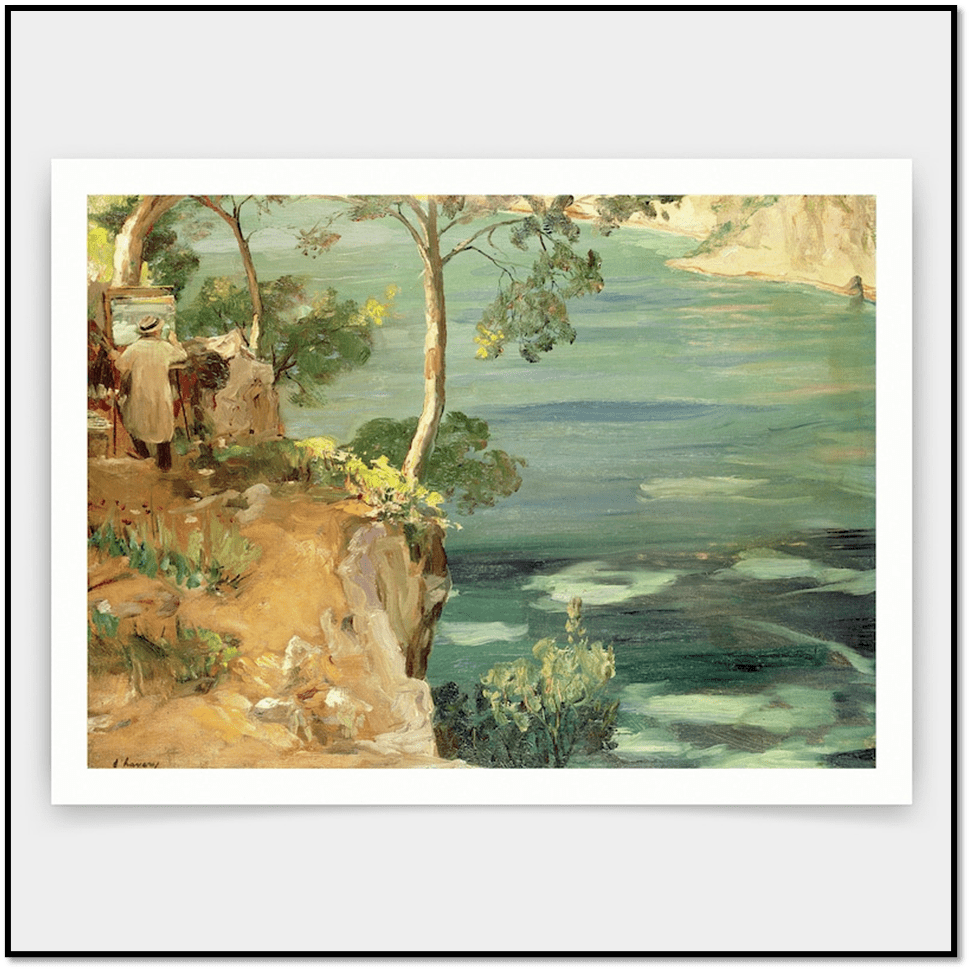

There is no other picture like that in the exhibition. Even though the motif of an Arabic viewpoint is used in the 1907 Evening, Tangier, the effect is merely exoticised, truly othered. Indeed I think the preference for a heightened view changed its meaning for Lavery at Hazel in the prompting to buy Dar-el-Midfah ‘between Tangier and Cap Spartel’ where they could view the meeting of the Atlantic and Mediterranean and yet be distant, in height too, from the base level of the politics of Morocco, which were becoming murky. The wonderful painting On the Cliffs, Tangier (1911 – the same year as Night, Tangier) is actually full of other political implications too, as Morocco sought to free itself from the French and Spanish, only to find the former even more entrenched, invading in 1912.

McConkey reveals that this painting shows the mother and daughter (it was Alice – Lavery’s stepdaughter) very close together because Hazel refused to allow her out of her site, even in such a secluded spot, because of the fear of unrest and growing despisal of colonialists.[13] From such a high perspective the Straits seem merely a view, the focal point, our eyes drwn by the ed and white being Hazel and Alice.

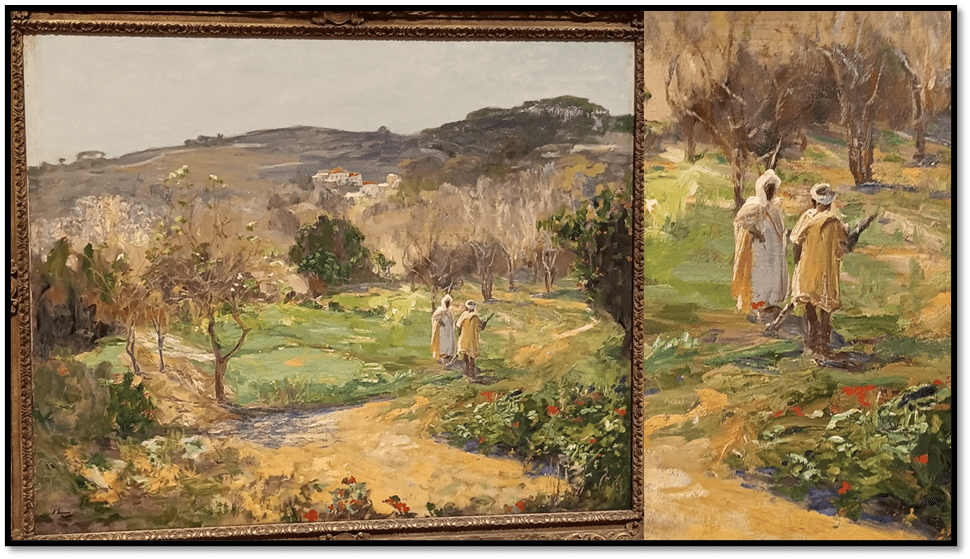

At near the same time the painting A Moorish Garden in Winter (1911-12) is apparently a most peaceable affair. McConkey says that though the garden scene was not his or a fellow white settler, it looks very like those places in location and tendance. We look down on it like the sun bleaching certain parts of it, and it is beautiful and peaceful. But what of the ‘Moorish’ gentlemen there. McConkey seems sure they are a ‘wealthy Moor consults his gardener’.[14] But it could equally be a dispute. Are they in dispute? In one sense they serve to exoticise the scene, in the Orientalist manner, but at others they disturb it. This shows the dual nature of superior views, sometimes their superiority may be in the process of being challenged as in 1911-12, it was.

Treatment of the means by which people of other races or identities are ‘othered’ from the presumptive type of the artist and the implied identity of his art’s viewers.

The painting above presumes that there is a process of othering that in part comes from taking a superior perspective on others, and from the use of stereotypes – of the Irish peasant or the ‘Moor’. You will remember the picture of Lavery’s boy servant, dressed by him in traditional costume quite inappropriate to his and more akin to their status and taste in the supposed international. I cannot know who ensured Alice stood on a chair so she towered over the boy, who would otherwise have been taller than she. Even in a photograph the family as a whole must look down and not up to such appurtenances however colourful and indicative of one’s refined internationalist taste.

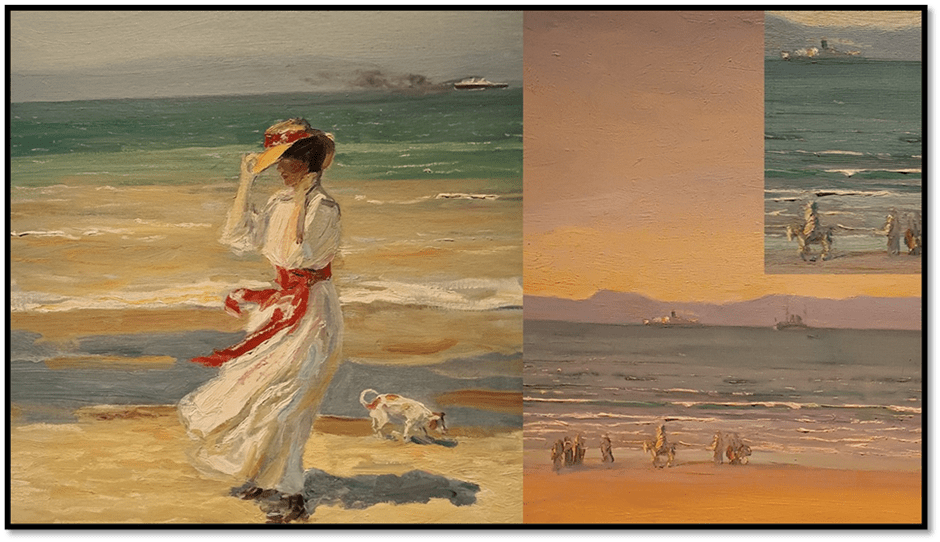

One contrast that really appealed to were two pictures mainly aimed at capturing the effect of strong winds on the Mediterranean in Tangiers Bay. We look directly at Eileen, his teenage daughter, (there is a chance it may be his model Mary Auras or an amalgam of both) holding her bonnet in Windy Day (1907-8).[15] Lavery’s aim is to capture visibly the invisible wind, even in the motion of Hazel’s shadow, her clothing, composure and of the sea. Much can be learned of the use of paint layering and impasto in this work in the capture of the signs of motion. But compare it to another painting with a similar intention on the surface of things: Where the Sirocco blows (1914).

From a high position, a rather impossible one, we not only view the motion of the notorious hot troublesome wind but the motion, in the same direction of an exotic caravan of’ Moors’, diminished from our viewpoint. There is more to this painting than the exemplification of Lavery’s skill at painting motion in oils. There is a scene that is not at all European, is exoticised and mysterious.

Fascination with foreign dress, especially light colours (and white in particular) also becomes a means of ‘othering’ an alien and colonised race as in the following two paintings in one collage. The small portrait (right in the collage below) of Daniel Santiagoe, The Curry Cook’s Assistant of 1888 was painted at the Glasgow International Exhibition when its subject visited to promote his popular book The Curry Cook’s Assistant; or Curries, How to Make Them in England, in their Original Style. It feels pertinent that the title of a book meant to assist ‘England’ (that might not have gone down well in Glasgow) becomes the man’s title in the painting, which is written in lavery’s hand on the painting in oil paint. Santiagoe is a man of learning but is received here as only as the servant he was (although in fact he brought four of his own to Glasgow so lucrative was the cookbook). Actually a quick sketch, it emphasises his role as an exhibit, as he was in the Indian Pavilion of the Exhibition.[16] The role of the ethic of service here merged with British attitudes to the role of service associated with the Indian sub-continent (Santiagoe was from Ceylon) and the exoticism of its people. There is a large red mark on the man’s clothing,a dhoti, perhaps representing the matk made by spices.

Even more intriguing in relation to the ethic of service is The Indian Waiter (1888) representing one of the waiters at the International Exhibition in the ‘bungalow Tearoom’ sponsored by Doulton’s pottery in praise of the Empire. Here the man is anonymous, entirely reduced to role and exotic appearance to go with it. He is in motion (coming from a downstairs space according to McConkey but I don’t quite get that) and has his and on his hip to balance the tray in his other hand.[17] Everything speaks colour, especially the rich fabrics of the turban and what may be gold jewellery on its tail that falls over his shoulder. The othering, for Western viewers is specifically feminised, made even more colourful by the drab faded bourgeois figures in black and grey, he might be about to serve. But his role is to the object of our gaze, in my view an eroticised gaze, othered in every dimension.

It is worth looking at the detail of that painting again perhaps because my interpretation might seem fanciful. The raised knee in the white dhoti may indicate motion but it emphasises too the body under the clothing. The face is handsome, the smile and gaze direct. This is not about him though but about the way exoticism and Orientalism made its lower classes available to Westerners’ imagination, and sometimes crossed boundaries, as with E.M Forster’s sexual adventures in both Alexandria and central India, where he served as the assistant of a Rajah.

Above I have tried to raise the problems of liking Lavery’s art in any straightforward way, but besides pointing to its oppressive and entitled background attitudes I hope I have also captured some of the wonderful nuance of the art, raising issues the artist may only have been half-conscious thereof. But clearly I need to end by looking at the chosen theme of this exhibition: place and location.

Dealing with the painting of PLACE and location in Lavery

One reason I am wary of the Impressionist label for Lavery is that his paintings do not much ever seem to be an attempt to capture a moment in time, through the effects of light. Where time matters it feels to me to have meaning in it. Lavery sometimes fed the notion that his art was a matter solely of the function of art to exist on its own terms as a abstraction of forms in a whole, as Roger Fry described Cézanne.

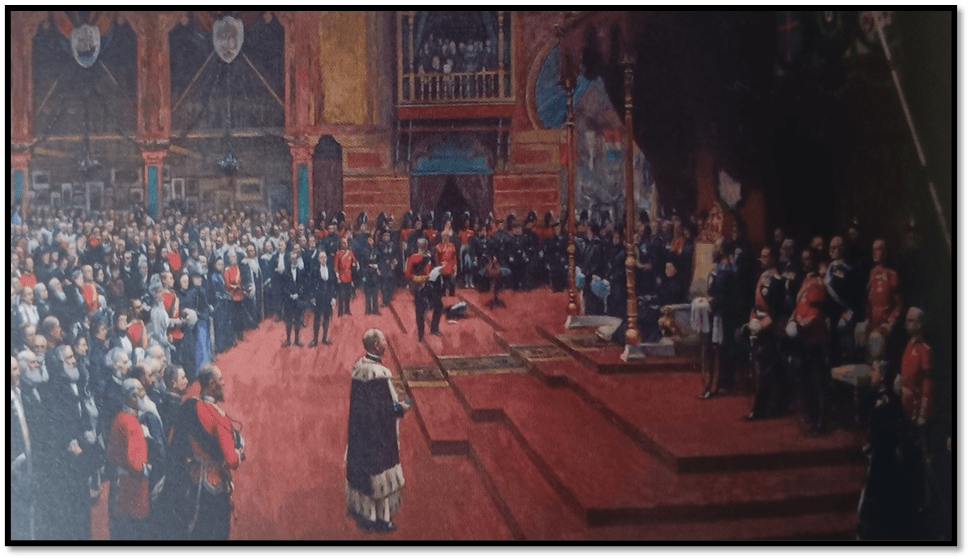

But mainly I think Lavery unlike Monet because he stressed the meaning behind his forms – not representational mimesis (a copying of what he saw) but its interpretation – what is ‘significant’ in the use of forms and the creation of form in Clive Bell’s popularisation of Fry. It is commonplace to chart Lavery’s obsession with figure painting of great men, down to Winston Churchill, his friend, from his painting of Queen Victoria’s State Visit to the Glasgow International Exhibition. In having to collect likenesses of many powerful people, I have no doubt that Lavery made this networking activity a means to achieve the vicarious power and influence, and perhaps he hoped wealth too, that he made his goal. But that painting is also surly a means of interpreting moulded architectural space as a symbol of a moral order that imperialism pretended to be – the raising of other races to an imperial standard.

I am glad to say that Lavery’s art however was not locked into such pious nonsense all the time. His happiest period in France ought to have been that period where he absorbed Bastien-Lepage and cemented an impressionist aesthetic but I think these paintings rather invoke to me the kind of moralised (or allegorised) figure and landscapes of the Pre-Raphaelites. In the artistic community at Grez-sur-Laing, I think what we find is a tradition of capture of form in ways that also had narrative and ethical meaning – the means of working Erwin Panofsky was to dub the Paysage Moralisé in the 1930s. Many art historians (of course) disputed whether such a reading of figures in landscape, afraid of the way that this might make visual art tied to literary art, but such objections now see passé. I sense a moralised landscape in Lavery’s work in Grez-sur-Laing. Here is, for instance, On the Loing, An Afternoon Chat (Under The Cherry Tree)t (1884).

McConkey discusses how Lavery worked en plein air and sur le motif, as if this were Cézanne.[18] I don’t buy this. These figures are so typed in terms of a moralised story. The young woman in April blue leans too evidently to show her breasts to the young man trying to hold his place in the onward stream of time with an angles punting pole. The young girl looks up at the older women as if trying to cause the latter to recall a more youthful innocence. The man does not step on the ground – his medium too fluid to be certain. Canopied by a fruiting cherry in bloom, the area around and between the man is covered with lush vegetation, but the foreground reads like a moral allegory, in the manner of Victorian painting, the ground almost barren and stony and pulled stalks ready to decay.

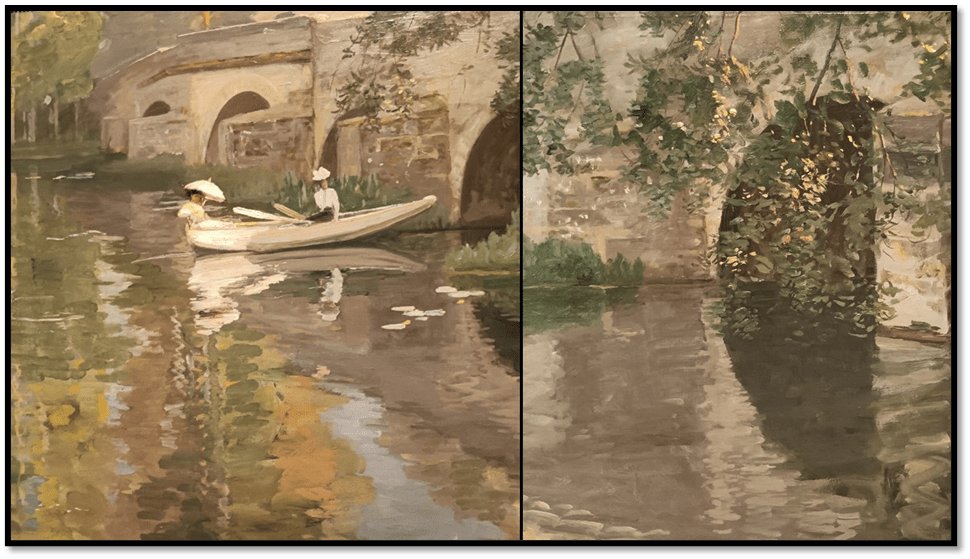

The beautiful The Bridge at Grez (1901) has less narrative and more potential symbolism, the boat gliding to enter the arch under the bridge and united only with the water’s reflective surface, regardless of the depths. Seeing this in the flesh makes one realise hoe flowering tree on the left stands out as if from the surface of the painting, suggesting something transiently beautiful and making the rest seem fragile. For me this is Paysage Moralisé – Lite. It reminds me of McConkey’s statement that Lavery may have been predicting the symbolism of modern movements.[19]

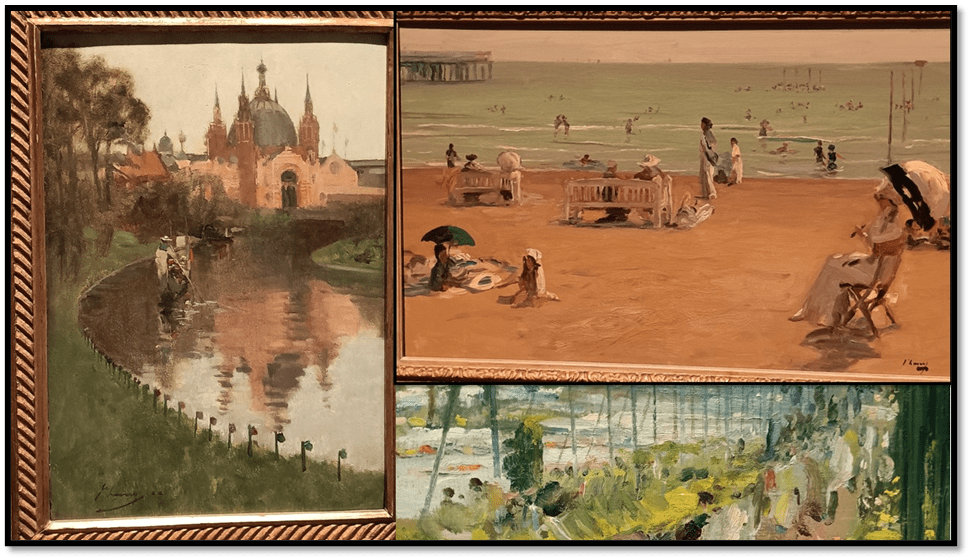

The landscapes of later work feel to me to take on space as if was not only itself but the break from mundane reality and work that were its scenes, ones of holiday or temporary leisure, for I include the ones at the Kelvingrove Pleasure Grounds with its fantastical architecture as left below in the collage. These were festive scenes that refused to work at all and certainly were far from ethics if not necessarily minor narrative of pleasurable ventures. The scene at the Venice Lido has all the longing and potential to surprise as its appearance in Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, but here, literally, no revelation or epiphany occurs or not yet. Henley Regatta is reduced to patches of colour in the excerpt from that late work.

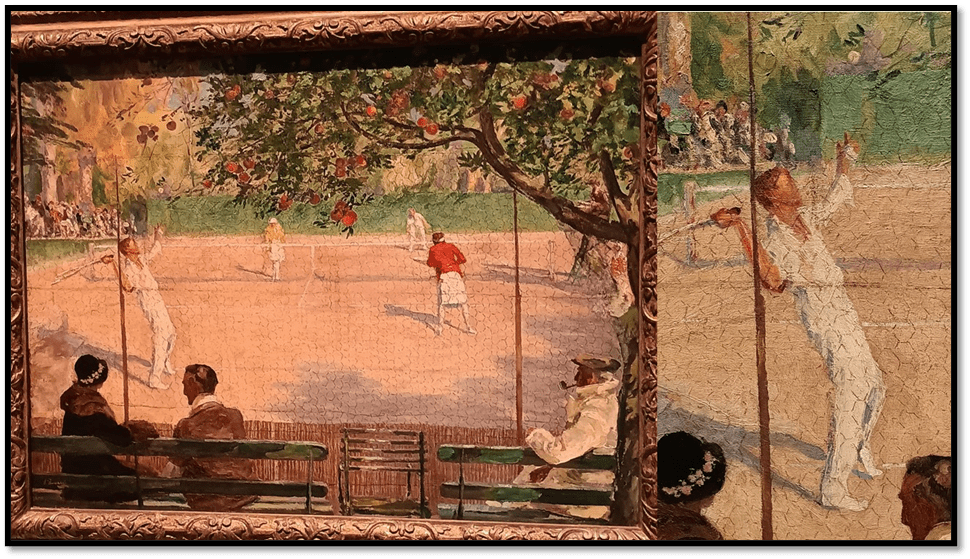

Cannes is probably the very essence of the leisured international class, and Lavery treated it as his after the sale of his Tangier property. They rented a house from the Guinness family – an Irish connection but internationalised called Villa L’Enchantement. His Tennis, Hôtel Beau-Site, Cannes (1929). It is a painting I kept returning to despite the leisured riches in which it rests. Its front row of spectators at the bottom of picture plane seem to remind you of ways of looking at what we see – the man taking more interest in the woman who seems to gaze upon the young tennis-player, caught in the up-swing to meet the suspended all. His shadow almost apes a crucifix he stands for flesh, not seen in the spectators in shadow who are over-covered by clothing.

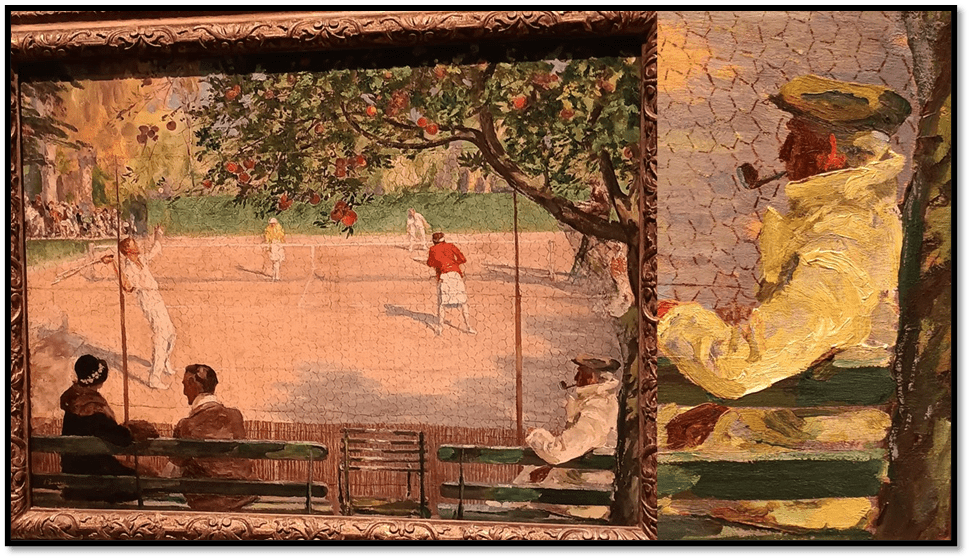

We are trained to detail here. Below see the grand effect of the yellow-coated pipe-smoker, the angle of whose vision meets he lady’s at the apex represented by the young male. The vision of both is foiled by a finely painted mesh representing the safety fencing of the tennis court. The eye is invited and obstructed in this way.

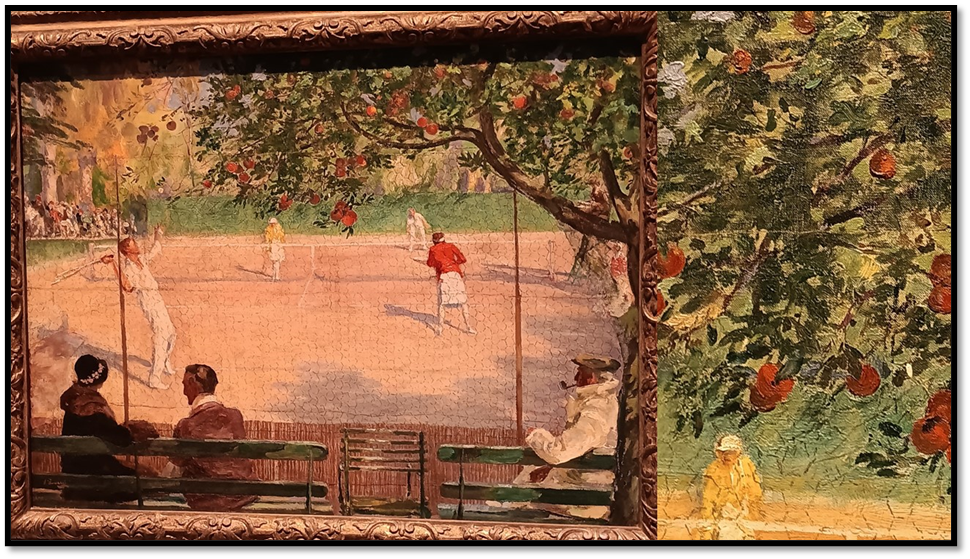

And finally I lingered over the fruit tree, whose fruit is palpable in thick oil that almost comes forward from the picture plane, probably because of thickness’ of the oil paint and its rich colour that rhymes with the coat of the only woman player (Hazel had been painted out).[20]

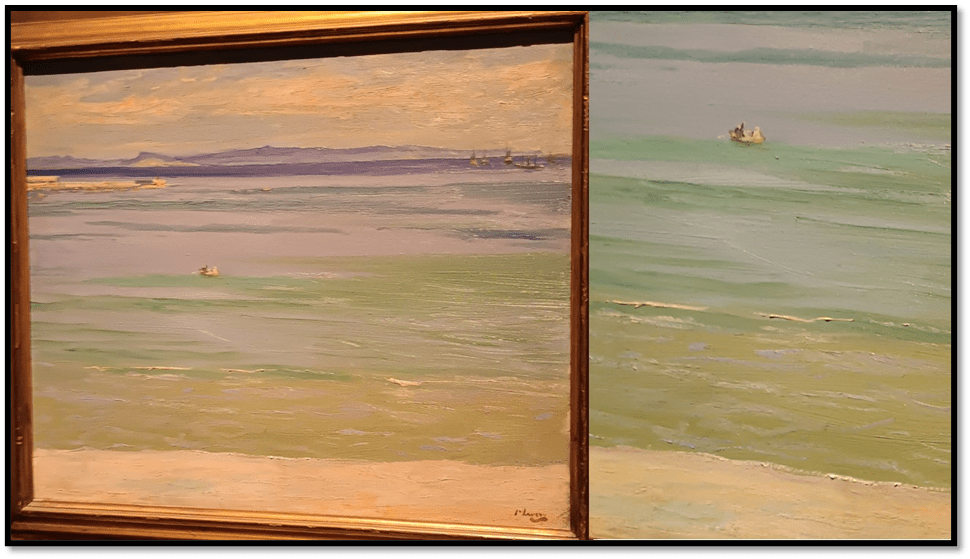

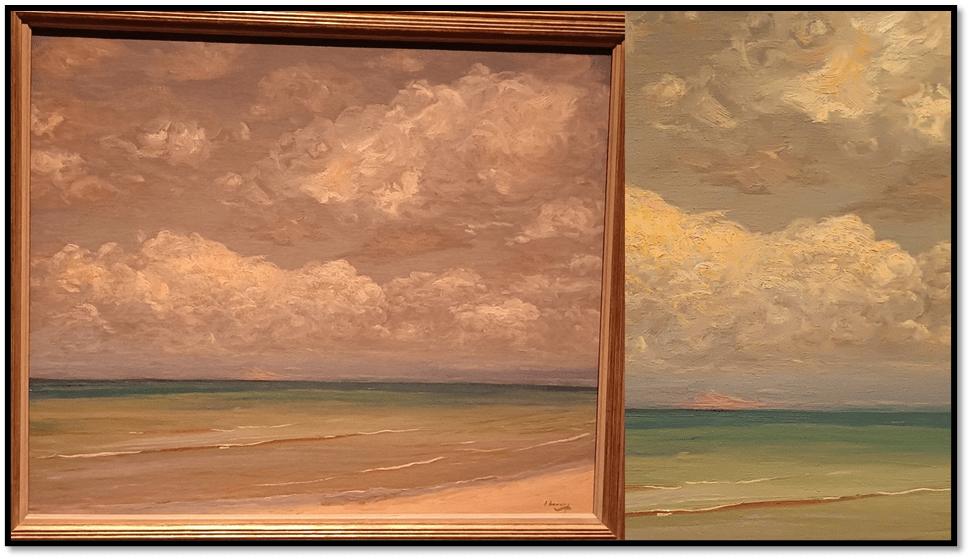

But even simple seascapes evoke place, but often abstracted in ideas of simple space and time. I think time is involved because they evoke seasonal moods and contingencies of weather, as well as the odd human event, that bobs mysteriously on the water as in the placid Tangier Bay, Sunshine (1920)

The little skiff contains human figure, coded as Europeans – he in colours, she in white apparel – the aim to show the almost windless atmosphere (they row and you catch the foam of his oar blade). It reminds me of Courbet’s contrast of the immensity of seascape and distant Spanish mountains. Cunningham Grahame, McConkey says, said it reminded him of a theatre with wooden sets representing those mountains, and perhaps this is so as if Lavery and family are only playing at being in immensity.[21] I moralise this so I can compare it with the different moral effect of The Southern Sea (1910) where human figures are absent. The sea equally calm seems rip for change heralded by gathering cloud, and the darkening and misting of the distant shore. McConkey thinks that one might ‘invoke Whistler and Courbet’ but adds: ‘neither gave such full measure to the tones and colours on the surface of the sea’.[22]

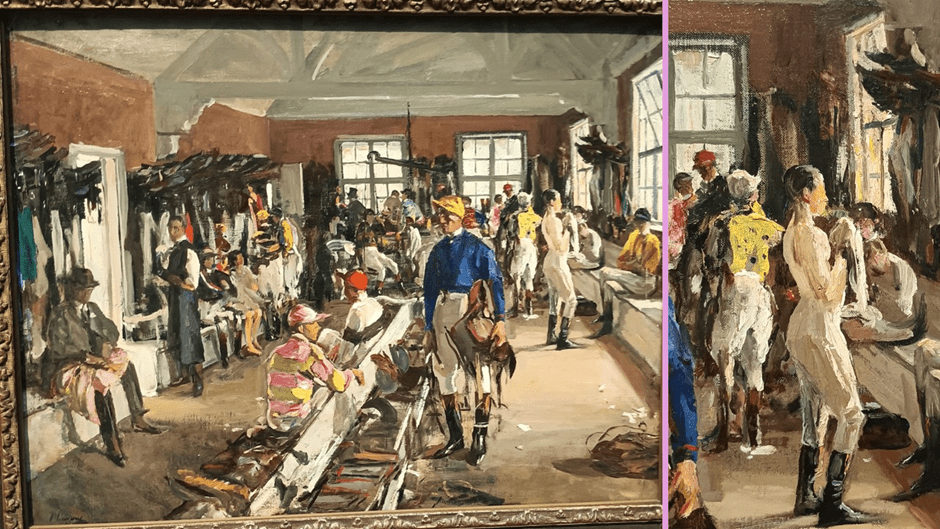

In social terms however limitless his interest in space became, he preferred interior spaces that were cluttered with social significance. Again, I was surprised I like The Jockey’s Dressing Room, Ascot (1923), whose subject is social exclusion (few but the privileged saw such a scene at Royal Ascot) as the presence of a gentleman owner on the left denotes. The focal perspectives are strange but as in the Cannes piece are pulled to young male flesh. The naked torso of one jockey (on the right) is almost dissolving in light. It brings new light to McConkey’s comment that he ‘brought special luck he bestowed on a winning jockey, something that earned him a special place in the affections of other riders’.[23]

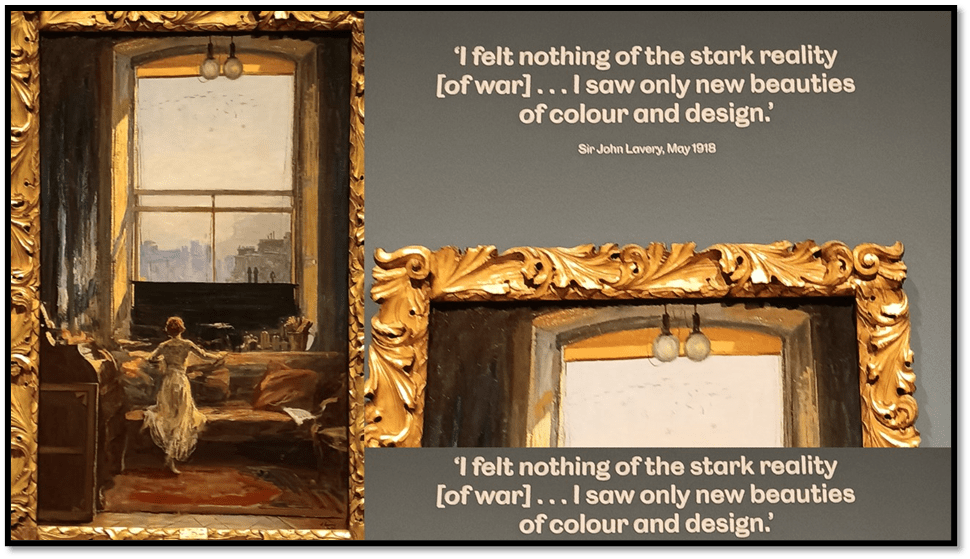

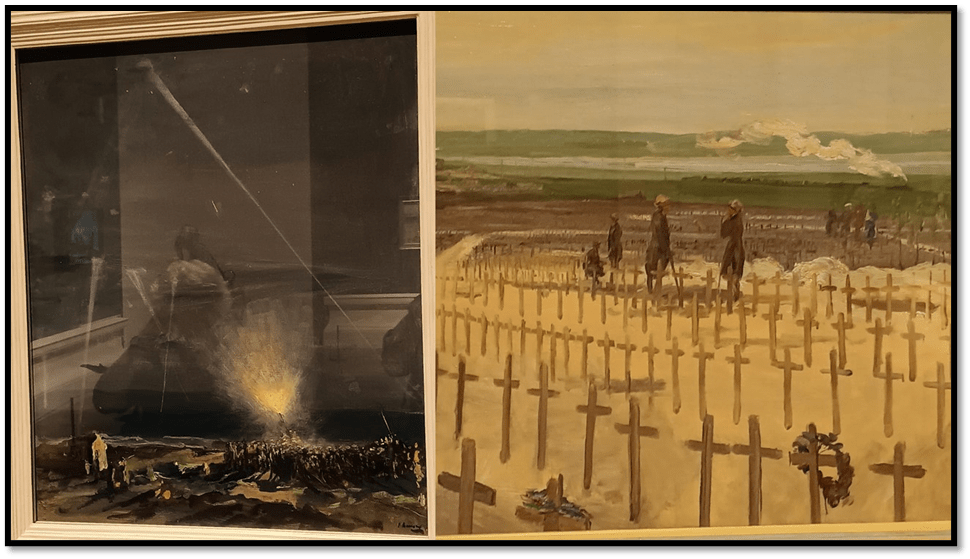

The war art is especially interesting but I intend to use it her to illustrate a point about Lavery’s method prompted by a bold quotation placed on the wall above the quite remarkable painting Daylight Raid (The Studio Window) , July 1917 (1917).

In the exhibition I contemplated the quotation printed on the wall above the painting. Ion the surface, its possible meanings shocked me a little. Was Lavery’s art really as absorbed in formalist aesthetics as this suggested, disregarding not only the moral implications of by warfare, but even the visceral realities of dying, dead and maimed flesh seen near to the front, where Lavery was never expected to go? Is that why we barely even see the 21 Gotha aircraft over North London in this painting, mere spots in the painted sky of a huge canvas, to the presence of which we are directed by the staged upward gaze of Hazel with her knee resting on a beautiful antique sofa, lovingly painted in rich colours glowing in light. Is it that the subject of his art, now as an Official War Artist, is itself being forced to succumb to the aesthetic impulse and the surfaces of the artist’s luxurious accommodation of his art. The press may have both thought so and yet not condemned Lavery. McConkey points out that the painting was praised as ‘a beautiful studio interior’. A Madonna placed in the dark space of the studio up-blind on the window, which explain Hazel’s kneeling attitude, was painted out by Lavery even further turning attention from the possible emotional content (possibly also removed because it underpinned Irish Catholicism). Hazel’s attitude is thus no more than merely a beautiful model’s pose, allowing the finessing of the painting of the fold in the thin lace dress she wears.[24]

As a composition it is faultless, but is it cold about the deathly dogfight in process, giving itself over to the circumstances and potentials of the visual over deeper meanings? The question runs deeper in A Coast Defence: an 18 Pounder Anti-Aircraft Gun, Tyneside (1917) = left in the collage below. Where the content is transformed into a beautiful pattern of light in the sky and reflected on buildings on the shore and on the top of incoming waves in the sea. If so, it is not the case in The Cemetery, Étaples (1919). This is a truly moving piece about the magnitude of war loss, not least because of the train passing the scene in the distance. McConkey says this ‘passing train in the distance, itself a poignant remembrance of nineteenth-century technology bent to modern warfare’ is there to define ‘the moment’.[25] I feel that undersells the meaning of the painting. The static figures of soldiers there to mourn their comrades killed in the war notice the train passing, its motion signified by the trailing smoke. The poignancy of the painting is that is about not capturing a moment, but signifying the moment that passes, hasting towards forgetting as well as memorial. It makes the wooden crosses even more poignant.

If that painting has meaning for me, even Daylight Raid can be seen again as a thought about art, Its pretentious machinery promising to capture and still time, whilst its reality is the stuff of passing, if cyclic time, daylight and summer morning dresses against the finality of death. The two globes in the upper window feel to me significant and moving. This painting is not just a formalist achievement. Turning from war however, I wonder if a painting can ever be removed because painting also lives as a pattern of colour and form on a flat surface.

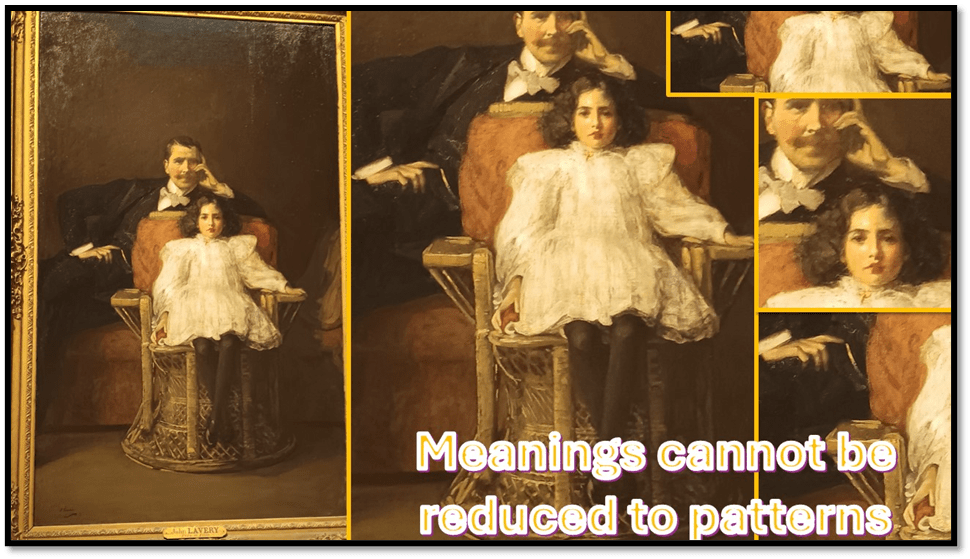

The marvellous earlier painting Père et Fille (Portrait Group) [1896-7] is of a stunning size. It bears down on you like a icon of patriarchy. Admired by Whistler, it is formally beautiful. The sitter for the daughter is his own daughter, Eileen, but this is less a painting of their relationship than of an heiress of power, an earlier form referenced Velásquez’s Infanta Marianna. If formally wonderful (and it is), meanings cannot be turned into mere patterns and even these have meaning.[26]

I tried to think about why this painting makes me sat that. I think it is because of the powerful effect in it of a flowing pattern of hands, that refuse not to have affect and signification, ones that rather queer the picture. The rhyme of male and female hands arced around an object in a vertical line contrast powerful control with nervousness – the girl grasps the cushion while trying to appear facially unperturbed. The mirroring of his right and her left hand in a downward slight diagonal (as the viewer sees them) spooks me considerably. This picture is far from simple emotionally and intellectually whatever the stated intention of it.

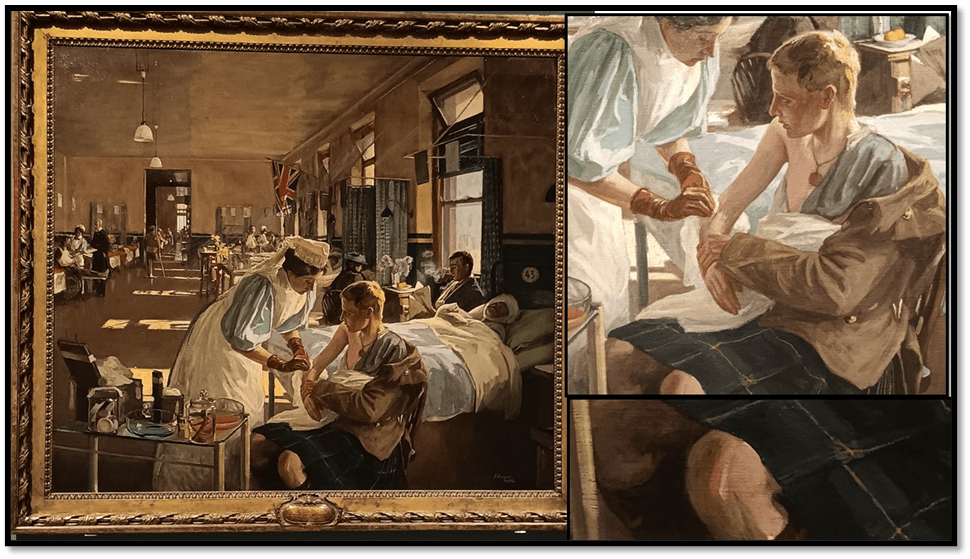

And war too has poignant meaning. I looked a long time at the huge Wounded, London Hospital (1915) done before Lavery was a war artist in 1917. There is a danger in being drawn by the chocolate-box pathos of nurse (based on a real ‘Sister Charlotte’)[27] and young Scottish wounded boy, here Lavery playing I suppose on his adoptive Scottish identity, but the boy is not sentimental and so beautifully defined, even down to the play of light on his bare knees below the kilt. There are marks of paint on that knee that might be a scar, or might not. The painting allows and facilitates the search of wounds and the depth of pain intended.

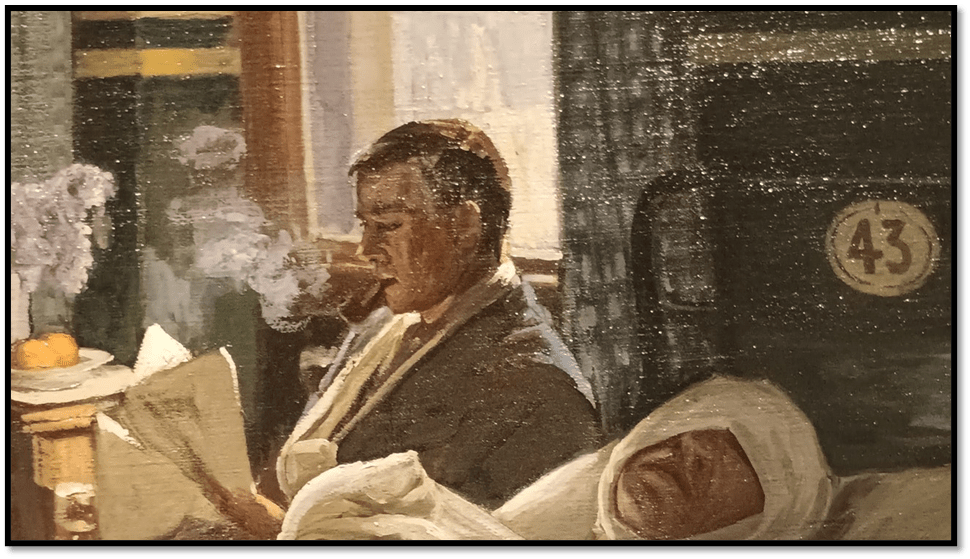

The painting excels because of its multi-perspectival character that continually questions the interface of wounds and pain with attitude and sympathy or otherwise for the wounded. Our eyes take time to be drawn to the right to see the silenced young man accompanied by a man (another wounded soldier) who sits reading the war lists and even blowing beautiful smoke rings from his pipe, whose face is quizzed by the light touching the tip of his nose,. What is his attitude to and feeling for the soldier labelled number ‘43’. This is unbearably moving, an anti-dote to Sister Charlotte.

But the true power of contrast around the effect of war is in the long perspectival pull diagonally from the picture frame level to the level. This painting has so many vanishing points . It even stops the eye by concentrating its focus on the drugs trolley (Lady Cynthia Asquith said it almost ‘made one smell the anaesthetics’), before it leasds to the light at a distant window in another ward, a soldier with one leg and a crutch being caught in transitory passing light on the way. It takes some time before we notice the Union Jack hanging limply from the wall on the left, just outside the many focal points of the painting. This is, I think, a wonderful painting and a good one to end on.

Art least, it would be if it not for that startling painting of his friend Winston Churchill, who, a painter himself of sorts and who accepted Lavery’s tutelage. The painting in which he appears, captures the eye in the gallery because of the blue tonal study of a Mediterranean inlet bathed in uneven light. In The Blue Bay, Mr Churchill on the Riviera (1921) seeing Government Minister Churchill takes time, painting from too far a distance to see the wonders Lavery sees and does capture. The Blue Bay, as it was actually called, steals the show together with the control of perspectives and colour that is painted art, unlike Churchill’s slavish attempts at mimesis. Mc Conkey shows how this quickly painted piece glorifies the colour of sea and cliffs, showing each varied by colour and depth in different ways.[28] Art wins, Mr Churchill – and although the evidence is ambiguous, isn’t Churchill seen from a superior point of view.

My time at this show in Edinburgh was not regretted, apart from the fact that it was so richer than I thought I had allotted too little between other bookings. I could go again and benefit. Come with me, please!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Kenneth McConkey (2023a: 12f.) ‘Lavery’s moderrnté’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland, 10 – 27.

[2] Ibid: 12

[3] Ibid: 20f.

[4] Cited: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jules_Bastien-Lepage

[5] Cited in Brendan Rooney (2023: 28) ‘The air of a man of the world: John Lavery and his public’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland, 28 – 33.

[6] Ibid: 32

[7] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 183) ‘Catalogue: 85’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland,

[8] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 170) ‘Catalogue: 78’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland,

[9] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 192) ‘Catalogue: 90’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[10] Cited in Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 88) ‘Catalogue: 27’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[11] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 108) ‘Catalogue: 40’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[12] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 148) ‘Catalogue: 66’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[13] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 117) ‘Catalogue: 47’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin,.

[14] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 113) ‘Catalogue: 43’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[15] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 106) ‘Catalogue: 39’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[16] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 78) ‘Catalogue: 22’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[17] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 79) ‘Catalogue: 23’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[18] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 46) ‘Catalogue: 7’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[19] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 58) ‘Catalogue: 13’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[20] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 19) ‘Catalogue: 91’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[21] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 121) ‘Catalogue: 50’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[22] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 115) ‘Catalogue: 45’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[23] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 178) ‘Catalogue: 82’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[24] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 154) ‘Catalogue: 71’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[25] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 164) ‘Catalogue: 76’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[26] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 132) ‘Catalogue: 57’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[27] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 146) ‘Catalogue: 65’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland

[28] Kenneth McConkey (2023b: 176) ‘Catalogue: 81’ in Brendan Rooney (Ed.) Lavery On Location Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland