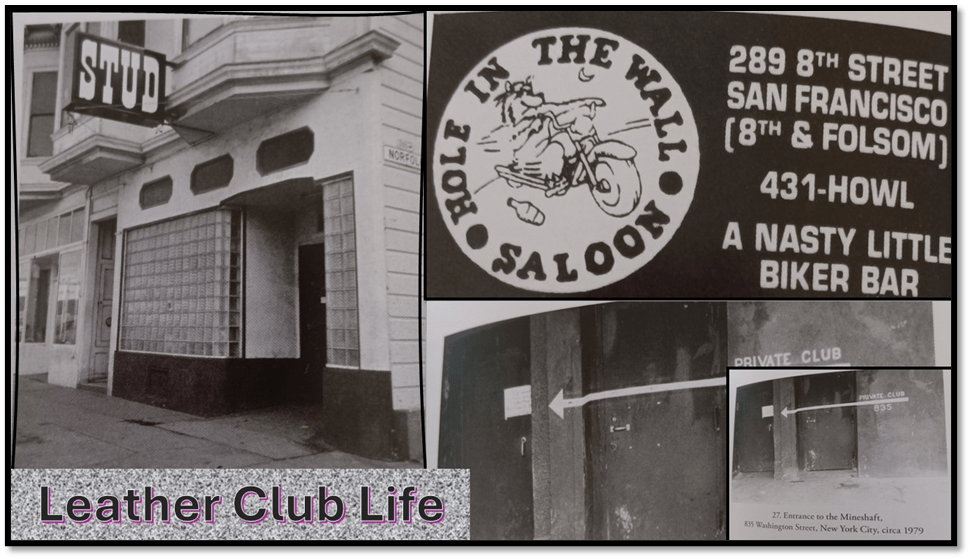

The history of which Thom Gunn was a queer part is one that is still alive but less predominant in modern queer culture, except in enclaves where the most important thing for a queer man is asserting that their queer identity still makes them MEN in essence, even if they also believe that being a man is actually a construct of psychosocial performance rather than a biological fact reflected in ‘male behaviours’. There is a heavy ideological version in the writing of some queer men opposed to the reflection of trans identities in lesbian and gay ones in, for instance, some work by Philip Hensher. See my blog on his 2020 novel A Small Revolution in Germany at this link. Thom Gunn was not a biological essentialist in any way that could be articulated but he did support the necessity for him and a group of men he found sexually attractive to adopt the pose and clothes of often the most undeniably male body imagery, which aligned to with preferences for the more obvious biological markers (or what are seen as such) of the claim to being a ‘man’. Though attracted to leather bars, his favoured bar for over eighteenth important months was The Stud, which despite its name, and Thom calling it ‘a “terrible” leather bar’ (in praise not horror), was mainly dedicated to high level drug-taking, psychedelia and fluid identity, such that it bore a mural of ‘a Tool-Box style leatherman’ (The Tool-Box was a very earnest hypermasculine leather bar) ‘dropping acid and transforming into a hippie drag queen’.[3] Andrew McMillan quotes Nott approvingly, saying that leather for Gunn indicated that first and foremost his was an ‘outlaw sexuality’;

Wearing leather contributed to the ‘tough, masculine image’ that Gunn sought to cultivate; one “fuckbuddy” recalled, “Thom’s principal (and perhaps only) physical fetish was, as far as I could tell, leather itself. Wearing it, touching it, using it”.[4]

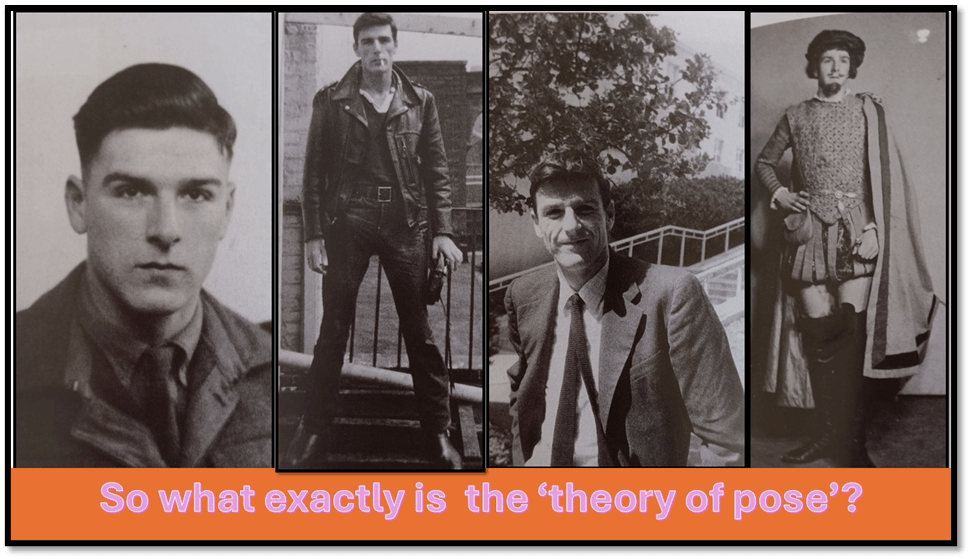

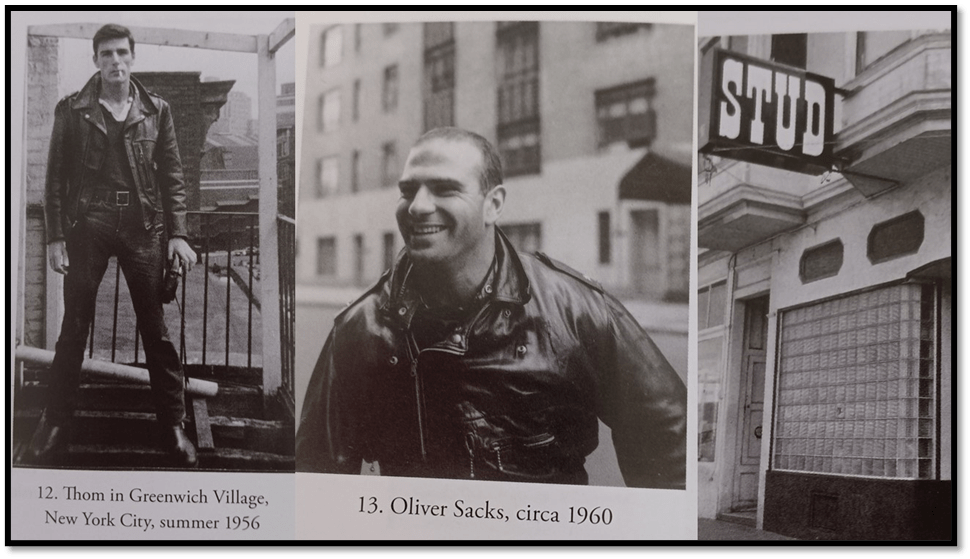

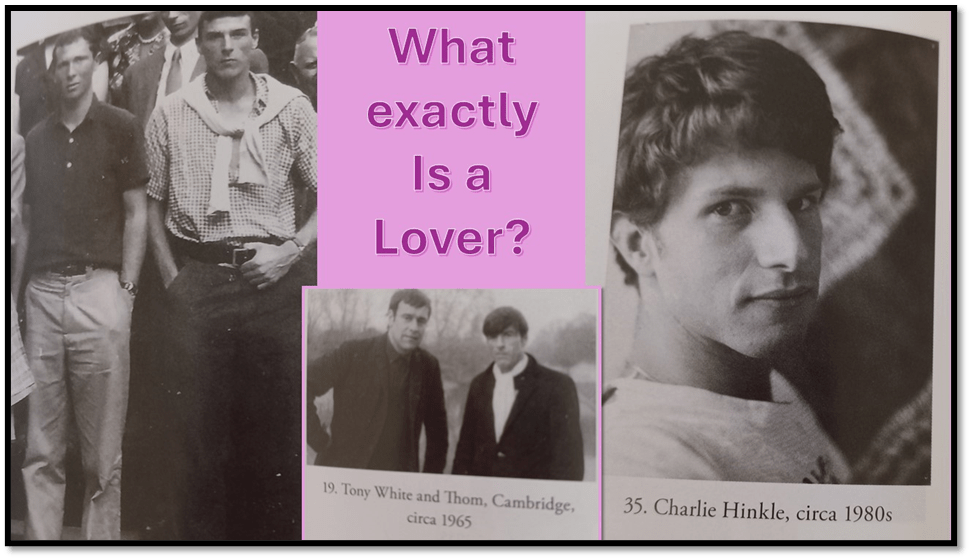

The fact was that Gunn could vary his persona massively between roles, as the instances below from Nott’s repertoire of sample photographs shows. Daniel Swain in the Los Angeles Review of Books goes further; suggesting that we can only understand identity in Gunn by avoiding notions of durable personal identity choices and instead by understanding Gunn’s ‘theory of pose’ in which what might appear to be a signalling of identity is in fact just an adopted form of role-play, with more or less consciousness of the performative nature of any instance of being, amongst the possibilities of looking ‘the man’. The pictures below show Gunnin the British army in 1948, dressed as a ‘leatherman’ in Greenwich village, New York City in 1956, as a professor of poetry and literature at the University of California, c. 1960, and in his most obvious form of role-play: being ‘Horatio’ in the the University College School production of Hamlet in 1946, only two years before his period in National Service. This is though, I have to say, the most delightfully ‘camp’ Horatio I have ever seen, rather more like Sir Andrew Aguecheek.

This idea of adoptive personae is described by Swain as the means by which queer identity was, almost experimentally explored in life, but also in the poetry.

From the 1970s onwards, Gunn was transparent about his “cool queer life” (a paraphrase from a Thomas Hardy poem): his work boldly explores cruising, BDSM, polyamory, group sex, and drug use, yet these explorations are often routed through complex metaphors, dramatic speakers, or, most commonly, an ironized, detached, almost sociological style of lyric observation (Gunn repudiated the postwar injunction to write poetry with “voice”). This approach led to a contradictory reception: some critics found the work embarrassingly personal while others were turned off by the sense of cold, formal distance.

Gunn’s intimate remove is connected to the “theory of pose” he developed while studying at Cambridge: “Everyone plays a part, whether he knows it or not, so he might as well deliberately design a part, or series of parts, for himself.” This theory of the pose was originally inflected by an undergraduate (and generational) infatuation with existentialism. As it developed across his life and work, however, Gunn’s theory of the pose became a complex aesthetic philosophy of identity. By turning personal experience into raw material without emphasizing the personality of experience, Gunn unpicks assumptions of individuality and its association with style. He wanted to write biographically without resorting to sentiment or the airing of personal trauma. (He was horrified by—and quite horrible about—the poetry of Sylvia Plath.) To affect this queer impersonality, Gunn turned to the history of the lyric.[5]

The attitude to Sylvia Plath tells us a lot besides revealing his loyalty to Ted Hughes (though he felt distant from the later poetry of Hughes) during the heavy beating Hughes received in the period from feminist critics for his infidelity and cruelty to Plath as his wife, that was assumed to be reflected by the ‘personal’ voice of her poems. But Swain might go too far in resolving every ‘masculinist’ gesture, image and tone in Gunn’s lifer (if not in his poetry on which he is superb) as a kind of act within a cyclical repertoire of constructions and deconstructions of identity. He considered Sylvia Plath as a fine example of a ‘Transatlantic’ poet, among whom he classified himself, but he did not value her poetry because of its ‘emotion’, which (in true male style in describing the inner lives of women) he called ‘hysteria’. He summed up the poems from Ariel before their publication, having been lent copies by Clive Wilmer, thus: “ The trouble is with the emotion, itself, really, … it is largely one of hysteria, …”.[6]

This statement may be more a reflection of his preference for the ordered play of the Elizabethan lyric of Thomas Wyatt that post Romantic confessional poetry, but the same can’t be said of his treatment of a friend, Charlotte, who was allowed to stay with the all-male elective family, only to find Thom constantly bickering at her and finding her sensibility faulty. From the household, Mike found Thom ‘nasty’ to her, Bob describing Thom’s behaviour to her as ‘shocking’, when he, in Charlotte’s words “would leap down your throat if you put a toe out of place”. There is something misogynistic in both cases, that may reflect a man who never chose to socialise with women. It can’t have helped that Charlotte had the same name as his mother, who having groomed him as a child (getting him to sleep in her bed whilst he was sexually mature and suppressing erections whilst there according to brother Ander) and committing suicide in a place where it was highly likely her sons would be the first to find her.

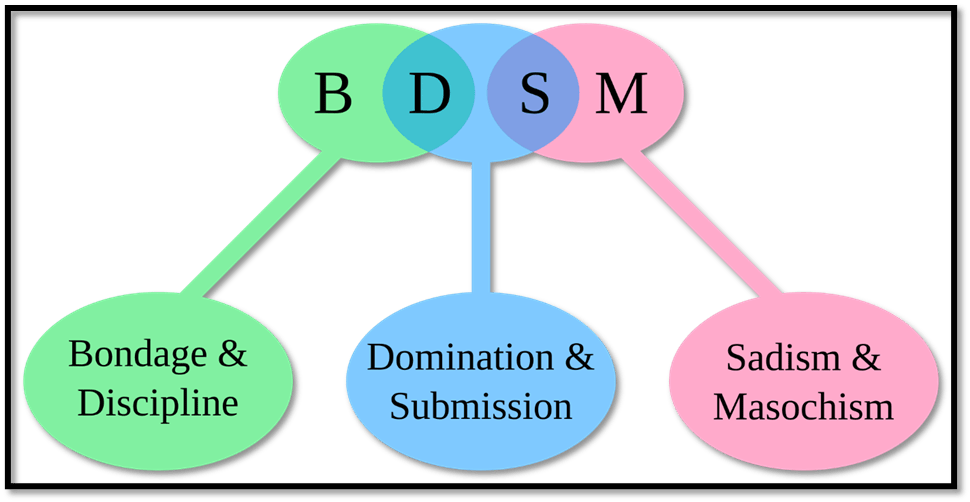

If his misogyny had roots in role-play, so too had his views about BDSM. As McMillan suspects with Nott, the personal preference for this set, in theory, at least of networked practices and interpersonal behaviours (illustrated in the helpful Wikipedia sourced graphic below) may have extended no further than dressing in and sexually playing with leather.

The BDSM acronym

Swain categorically denies that BDSM was more than a kind of metaphor for exploring what is generalisable as metaphor from BDSM practices in the making of images of the poet and in the poem:

Gunn was still happy to play the part of the “transgressive” poet. He was thrilled when a local gay paper described him as “nouveau riche leather-man Thom Gunn.” … He wrote, “I have no illusions about the true value of my image. It’s a pose, but when somebody wears a suit he is posing as much as I am.” The equivalence here works both ways: it is not just a point about queer artifice; it also describes bourgeois self-fashioning. … At the same time, even Gunn’s nonsexual poems capture something of the tension and excitement of sex. In a sense, he cruised the reader: “A good poem is simultaneously a tentative and risky cruising, a complete possession and orgasm, and a huge leather orgy.”

In summary Swain says:

Gunn did not valorize BDSM and struggled to reconcile it with his hippieish and bohemian conception of love: “I say that bdsm is a form of love […] but I don’t think that goes quite deep enough. Is it compulsive behavior perhaps, and how does it relate to my conscious values?”[7]

In fact then we can go too far in equating poetry with life, as Andrew McMillan insists he likes telling his students in his review of this book. However, the quotation from Gunn given by Swain shows too that Gunn does not deny that it may constitute a compulsive behaviour in him even if at odds to his ‘conscious values’. Nevertheless Sam Leith, reviewing this book in The Guardian has a point in saying that though one might think Gunn’s life would be full of continuing experimental ‘incident’, it surprisingly isn’t. So much so Leith feels the biography is 200 pages too long and might easily cut out of that length ‘month-by-month descriptions of not much happening, or fastidious accounts of changes in the décor or bar staff of the second-best pickup joint in the Castro’. I think this may miss much that those of us who love Gunn are relieved to find in the book. For here was a poet who valued a job in ‘a tough queer bar’ as much as a ‘damn contract’ from Harvard University that stopped him taking the job in the bar.[8]

It is typical of Gunn’s total lack of discriminatory prejudice against people who are not in the literary world, or well known in other ways, that indeed makes him special. Andrew McMillan, for instance, praises him and Nott for adding personal detail, almost on behalf of the queer community (and certainly me), at the end of a chapter on HIV on the West coast USA of the time, ‘recording the names, along with the dates of birth and death’ of ‘thirty-seven friends he had lost, or would soon lose, to AIDS’.[9] Other critics miss that – for them Gunn is only a fact in literary history. There is something similar noted in Steve Donoghue’s review in Open Letters who shows that many people regardless of sexuality loved Gunn’s open and caring attitude in real life. He cites this:

When the poet sees his friend Steven Fritsch Rudser walking along the street with his four-year-old adopted son, Nott shifts to Rudser’s thoughts about Gunn: “People talk about his poetry being a formal expression of dirty things, of drugs and sex and all that kind of stuff,” Rudser later wrote. “That’s true: even though he was into leather sex and bondage and whatever, he was really personable, and he was one of those people who, in my interactions with him, I always felt better after I talked with him for a couple minutes.”[10]

Rudser was a gay man who adopted his child, aged three-and-a-half in 1986, undergoing abusive intrusion from social workers in the process.[11] His sexual life was quizzed and this may explain his reticence about ‘dirty things’ in Gunn’s reputation here, some six months later. The point is that Gunn cared about people who cared about people and not entirely for those who had a well-known name. What is clear here is that this was not a caring linked entirely to masculine identity roles, even if he did like ‘rough’ men.

And although that is still the case we can’t forget the collusion that Gunn allowed himself to have with the roughing uo, in print at least, of men who failed to display that they were properly men, in poetry and life. At University College in the 1970s I remember the fuss when our poetry Professor, poet Stephen Spender, attended a lecture by Thom Gunn, visiting from the States. It was reported to us, by Dr. Keith Walker – such a gossip but a dear friend of Stephen – that Spender had gulped before he told Keith that Gunn ‘was dressed entirely in leather’ and obviously, though this was not said to Keith, an image of desire. All of us GaySoc students knew by heart the lines of Gunn’s below, from The Sense of Movement, which parodied Spender’s poem The Truly Great (“I think continually of those who were truly great”; see it at this link):

I think of all the toughs throughout history

And thank heavens they live, continually,

I praise the overdogs from Alexander

To those who would not play with Stephen Spender.

Some thought this was an attack on a sensitive, and now older, poet whose homosexuality was a matter of record: recorded by Spender himself in World Within World, his autobiography. Nott tells us that Gunn insisted that ‘he was not attacking Spender’s homosexuality’, but rather fighting against elitist notions that equated passive sensitivity and not action with poetry-making:, ‘the aesthete’s effeminacy’ in Gunn’s words: “ I was attacking a kind of nambi-pambiness which I don’t associate with homosexuality any more than with heterosexuality’.[12] But attack it was, and one that fed too easily into a culture of queer masculinism that hated the effeminacy associated with homosexuality in popular culture and some theories of the aetiology of queer sexualities. I think the point of the poem is however that there is an elitism involved in praising the ‘refined’ rather than the ‘tough’ great.

The sole and dedicated desire of manly men, including the one he made himself into in order to be ‘hot’ is not a pathological symptom, of course, attributable to a man who grew up feeling he lacked this image, which he sometimes claimed. Nor did he use the pose just because it was the easiest route for men who had the basic embodied resources, or could gain them at a gym, enabling them to ape the fashion for group sex, manly affectation of hardness (to pain or any other vulnerability), and promiscuity. The specialisation of desire was also based on the belief that the markers of masculinity were also those of a class of men that was not effete and oppressive whose power based solely on social status but of men validated socially as working class or in manual labour. Of course, we are talking only about image here and the actual social class of some of the people who adopted the image was much more fluid. (It was a matter of fun when I was a queer student in 1970s to make fun of upper middle-class lads who put on leather, and more slowly muscle, to pass themselves off as ‘toughs’, driving in Bentleys to the Coleherne with a biker’s helmet on its back seat to don for the walk to the Coleherne).

However funny though there is something also quite heartening about the felt need in these men to slough off class based affectation of being in an elite. If this involved a working-class ‘pose’, why not? As Gunn himself said, cited by Nott, and already quoted above from Swain: “I have no illusions about the true value of my image. It’s a pose, but when somebody wears a suit he is posing as much as I am.”

And yet Gunn I think constantly saw manliness as strength, and femininity as weakness in ways that had an oppressive effect sometimes. I feel it is there because it lead to imagery in the poetry that can be read as suspiciously discriminatory against any kind of personhood that invalidated binary gendered norms. In the poem Tenderloin, for instance, (where man is ‘meat’) there are images of queer degradation that are oppressive in many ways but not least in antagonism to feminine poses: ‘gentle / black whore, foul-mouthed / old cripple, snarly skinhead / Tottering transvestite, etc.’. Tenderloin is one of his best articulations in a poem of positive male-on-male sex but there is something that ought to make us pause in these lines, not least in the word ‘cripple’. There is something amiss too in the transcoding of sexuality and sex/gender that reveals something infantile, and certainly with a kind of teenage male narcissism in the sexuality of the poem. Am I wrong to see this as a problem?

Whether a problem or no, it was an important one in the period of Gunn’s posing as a leatherman. It needs looking at too in the considerably complex life-case of the neurologist Oliver Sacks who also, and with Gunn in the flesh, pursued male leather / biker fantasies. Nott tells us Gunn describes Sacks on their first meetings (Sacks being merely a student) as ‘a queer, colossally big London Jew called Wolf … who says my poetry changed his life’. What Gunn liked was the masculinity (see collage below) but when Sacks began ‘to want me far too much’ after Gunn had sex with him, Gunn quickly dropped him, seeing him as ‘obsessive’.[13]

Male images mattered as a description not only of the clothing and size of a man, for these are deceptive and can be mimicked. The pose of manhood had to be psychologically manly, which for Gunn meant independent and free of affective bonds. I think there is a problem here in terms of the building of sound queer intercommunion. For Gunn, definitions of who amongst his group was a lover or of a man who met his sexual needs differed. This is not a view not known now and, honestly pursued, harms no-one, if ways and means are found of bringing about this potential dual management of oneself in the network of your relationships that doesn’t harm others unconscionably. In Gunn’s self-management, it seems he very often assumed acting openly just as he liked when he liked should be enough to do to modulate harm to people who loved him, despite his kind nature in non-sexual and non-romantic relationships, like that with Rudser mentioned above. Sacks, for instance loved the ‘tenderness’ he saw in Thom but was punished for seeing it and thinking he could depend on it in building a closer relationship.

As a young man Gunn had no problem maintaining his independence and sense of existential freedom, which characterised the biker in his famous early poem On The Move. He could and did love Mike Kitay (left in collage below) all of his life. What did it mean, however, to be Gunn’s lover, Kitay wondered? Kitay wanted a monogamous relationship and wanted it with the different men he became sexually bound up with throughout his life, even living with Thom, so that he was laughingly named by the household, ‘a serial monogamist’. Nevertheless his hurt at Thom’s insistence on separating love from bodily needs was real and enduring in his witness to it. Gunn was, it seems, like this with all the men he called lovers, though as he aged, he feared that the younger manly men he was attracted to, such as Charlie Hinkle (right in collage), would lose interest in him and eventually dated men who used and robbed him. Hinkle did lose sexual interest but Gunn cared for him through his long dying of AIDS, whilst still living with Mike Kitay and his succession of partners. This is love, without doubt but complex love.

The man he loved until the latter’s death however is the best example of how Gunn treated people he desired and who only grudgingly returned sexual interest. For Tony White that was because he identified as heterosexual (centre in collage). Like Kitay, he met Tony at Cambridge. He described Tony as ‘a bear’ of a man, and, though Tony never thought himself gay, Nott somewhere points out that there was an experience of oral sex with Tony that Gunn considered a highpoint in his love-life. His love of Tony continued at a distance and Gunn kept a photograph of Tony with his friends near in him in his room (the one below). He is indeed a lovely bear.

However Thom’s beliefs in masculinity must have impeded his true ability to relate to the big bear manliness of Tony White as the latter actually experienced it. When Tony died, he was at the time helping a psychiatric doctor with a study in male impotence. Would Gunn have responded well to Tony spilling his heart on such a subject? We can be sure he never did. The relationship was founded on Thom’s belief that both he and Tony were ‘Stendhalian heroes’ (models Gunn believed in all his life), with Tony being the very model of virility, examples of which Thom had ‘glimpsed on the road in France’, and an icon of ‘personal freedom’ and male strength: the greatest possible amount of energy without being a monster’.[14] One almost feels as if one were in a Stendhal novel.

These silences around male vulnerability were, in my view, the deficiencies of the queer model that the period developed in people keen to create a new image of queerness free from the stereotypes of the intermediate sex held by enemies, and some friends, of the queer movement. That said friends of that movement, Like Edward Carpenter, made much of androgyny that was not Thom’s model of the object of desire. He favoured Whitman as model without realising that for Whitman the ‘dear love of comrades ‘ was also a get-out clause when accused of being queer. No! He believed in ‘manly love’, Whitman said.

These issues emerged with Kitay constantly. Kitay’s wish for monogamous commitment was constantly knocked back by Gunn from the beginning. He largely hated the ‘gay marriage lobby’ apart from the case of poet James Merrill, whose ‘marriage’ with David Jackson was acceptable because it allowed each partner ‘to take the other for granted, to depend on the other’s love without being in a state of constant erotic or passional tension’ by which he meant that each partner was free to serve erotic needs elsewhere.[15]

But this view of permanent relationship had other issues related to it. Just as I doubt that Tony White could ever have spoken of male impotence and its emotional sequelae to Gunn, so Mike was never able to speak of the depressions he experienced. I wrote about that in passing in an earlier blog (which can be read at this link). There I said (the incident relates to Thom after hearing of Tony White’s death):

In Michael Nott’s 2024 biography of the poet Thom Gunn, the man closest to him throughout his life, Mike Kitay, is quoted as saying of Thom first that, ‘He was probably depressed but he would never say that to anyone. He would never act depressed. He would always be cheerful, dancing around the house in his big clompy boots’. Some time later Mike expressed himself more directly about Thom: ‘He needed people to think he was happy, … And mostly he appeared happy, even manic. But sometimes, when no one else was around, he’d lean against the kitchen sink and bow his head and moan, “I’m old!, I’m old!”‘[16]

There must be many reasons why Thom Gunn, whatever he might also be feeling, thought he needed to know that other people thought him to be happy. The pressure is often heavy or thought to be on males, and queer or gay men in particular, in the light of the pathologisation of the thing that got medicalised by the name ‘homosexuality’. I grew up aware of Gunn but, like him, I felt the pressure to think perform in a way others thought ‘happy’, lest the unhappiness be seen as a symptom of the fact that my attractions romantically were to men and not, romantically or sexually, to women.[17]

Whatever, the reason, Kitay had long known that if happiness was a pose too in Thom, then it was because:

“In the early days, when I learned that Thom couldn’t deal with – didn’t want to deal with – my depression or anything heavy, I made that adjustment, … I was always angry that I couldn’t share that. I share. I’m a sharer. Thom was not a sharer and remained not a sharer”.[18]

That the masculine pose obsessed by personal freedom and the absence of bonds had a downside is I think clear from Kitay’s words but not only those. However wonderful Gunn was with his friends with AIDS, sickness like aging were things that unmanned a man, made him weak, and that was not easy for Gunn and for me is articulated in the phallicism of the poems ‘conceits’ (the English Renaissance term is particularly appropriate to Thom as the champion of Thomas Wyatt and Fulke Greville). His poem on a lover / friend, Norm Rathweg, rather embarrasses in its beauty in imagining death, in that it ‘wasted’ a body, took ‘class’ away from Norm in his own gym in To the Dead Owner of a Gym, because of the grandeur of his remembered masculinisation:

Of your gym, Norm,

In which so dashing a physique

As yours for several years

Gained muscle every week

With sharper definition.

It all reminds me of the biker of On The Move, who:

Bulges to thunder held by calf and thigh.

In goggles, donned impersonality,

In gleaming jackets trophied with the dust,

They strap in doubt – by hiding it, robust –

And almost hear a meaning in their noise.

In the better verse of his later work, in the poem Looks, the poet’s need in looking at a man is to:

To focus on his no doubt sinewy power,

His restless movements, and his bony cheek.

These lines are beautiful in respect of their meaning in terms of describing the man of Gunn’s desire and the man he now sees before him dying of AIDS where ‘the restless’ and ‘bony’ become symptoms of loss and illness not marks of masculine beauty.

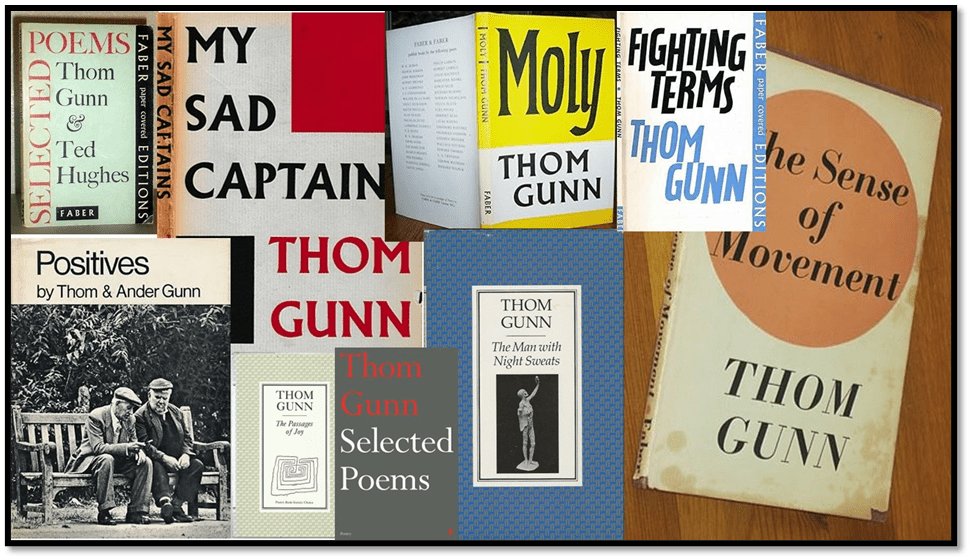

Of course what matters is the poetry of Thom Gunn and the lines above are technically brilliant and beautiful. However, my life themes shadowed Gunn from a distance but without the manly appeal. Gunn’s Fighting Terms came out in the year I was born, I studied him at O level in the famous anthology with Ted Hughes poems and he was talked about whist I was at UCL, rather wistfully by Stephen Spender, and by Karl Miller who became head of English. Nott tells of Gunn’s lifelong friendship with Miller made at Cambridge, though Miller was only a distant friend to anything ‘queer’. How Thom articulated queerness then matters to me, as it did for different reasons because he is younger, Andrew McMillan, and because Andrew is a poet as I am not.

Why does Gunn matter as a queer model? I think it because of his admitted partiality of kind as a campaigner for a queer polity, despite his brilliant modelling of the queer ‘chosen’ or ‘elective’ family as an alternative to the biological family. He lived too much in the city of men, let’s say. Swain is more positive about all that, like McMillan, but I think this manifests the problems:

Gunn’s depictions of a cool queer life also contained a critique of queerness’s attachment to coolness. His poems skewer the pretensions and inflations of queer culture, its normative nonnormativity. As an example, the poem “Seesaw” explores the act of cruising for public sex through the conceit of suburban playground equipment. In a bathhouse poem, “Saturday Night,” Gunn is interested in moments when meaningful difference dissolves: “In our community of the carnal hear[t] / Some lose conviction in mid-arc of play.” But gay culture doesn’t have to be a utopia, or even change a city, to be meaningful:

If, furthermore,

Our Dionysian experiment

To build a city never dared before

Dies without reaching to its full extent,

At least in the endeavour we translate

Our common ecstasy to a brief ascent.

In the end our queer polity does not need be ‘Dionysian’ in nature. Such cities die without some kind of Apollonian attempt at the harmonic and understanding of diverse needs. That doesn’t mean giving in to heteronormativity but it does mean a framework in which diversity is respected, even the ‘tottering transvestite’, who deserves a more understanding label because they are human. The hopeless basis of masculinity as the foundation of our city is a flaw and this is why it, like all human erections in the end, it will collapse. You can’t build anything on the hard phallus unless you realise that sometimes it is soft, however long you avoid orgasm as Gunn heroically did to lengthen his sometime 11-hour sex-sessions according to Nott. Steve Donoghue in a review in the online Open Letters says of Gunn:

As one of the many people commenting on his life mentions, Gunn’s life was characterized by “a square facing of the abyss,” and readers of A Cool Queer Life will get all the bone and tissue of that square facing but no hot blood, and certainly none of the abyss itself.[19]

Donoghue blames Nott for that, for being too scholarly and objective in approach but I think he is wrong. Surely, Gunn, by refusing to face difficult emotions outside of ‘happiness’ in friends, lovers and himself, left too much human business for a mask to manage. If we make a queer-friendly city it must be one of persons of hot and cool blood, which includes achingly slow as well as fast racing blood. A city just of men, as Gunn understood that too often, is impossible because it lacks empathy at crucial moments, where it finds itself confronting inevitable failure, diverse capabilities, sickness and death. Nearer the end we hear of Gunn reading Browning. Would more of this had moderated his poetry of existential certainty in the mask of manhood. His problematic relationship with Mike Kitay’s desire to domesticate their relationship sexually, Gunn wrote about in the 1954 poem “Tamer and Hawk” using in Swain’s words ‘a conceit of domestication to capture an erotic dynamic of not-quite-total submission’:

You seeled me with your love, I am blind to other birds— The habit of your words Has hooded me. […] Through having only eyes For you I fear to lose, I lose to keep, and choose Tamer as prey.

The poem uses the hawking metaphor ‘seeling’ wherein the hawk’s eyes are sewn up to make it dependent on its trainer and not its predatory senses. That is what he is telling Mike he is doing to Thom, sealing his eyes’ and ‘I’s’. Gunn’s hawk turns on its tamer and rejects him (not that Gunn did that to Mike exactly). I think the poem probably goes much deeper but there is a sense in which it glories, in the hawk metaphor, in very toxic masculinity, however wonderful the poem and it is. It is the same toxicity as in the lines from the great late poem The Gas-Poker on the implement of his mother’s suicide. In it she chokes on a phallic symbol intent on being a lyric instrument thereafter hereafter and muting her effects on him.

One image from the flow

Sticks in the stubborn mind:

A sort of backwards flute.

The poker that she held up

Breathed from the holes aligned

Into her mouth till, filled up

By its music, she was mute.

In The Man with Night Sweats (1992), which I have used a lot above, the death of a friend with a breathing tube in his mouth is also a kind of pastiche of oral sex in the ending of Still Life:

I shall not soon forget

The angle of his head,

Arrested and reared back

On the crisp field of bed,

Back from what he could neither

Accept, as one opposed,

Nor, as a life-long breather,

Consentingly let go,

The tube his mouth enclosed

In an astonished O.

Swain misses that comic moment of tastelessness in saying:

As the dark pun of the title suggests, the poem offers an ekphrastic meditation on the exact transition between life and death. The arresting and arrested final image tellingly inverts the relationship between breath and mortality in “The Gas-poker.”

Gunn was resolute to the last of his best poems not to soften his stance on the existential truths. People die and our memories live in that self-definition they sought in moments where a characteristic, maybe an idiosyncratic sexual behaviour or absence of one, defined their being, such as the living resistance of a man not keen on oral insertions but forced into one in death so that his mouth is an ‘astonished O’. How are we to read these extended conceits, so like those of Elizabethan poetry and purposely so. They are not weaponised as in John Donne for stock sexual seduction. I think we must read them as fleeting thoughts full of contradictory meanings – some unpleasant and toxic – like the sense that the speaker enjoys reliving these moments of survival over men dying.

However, it should be obvious to you that I am in awe of this poetry and only suspect that it overbears with the ‘hardness’ he admired in his pose as a queer hardman. There is much that is ‘soft’ in the great The Man with Night Sweats. Colm Tóibín says so correctly that these poems ‘even admit an awkwardness at times, which was something Gunn admired in Thomas Hardy’.[20] However, I think the time of the hardman as the aim of queer male being should now be a thing of the margins whilst some of us go on to explore the nuanced options in life and literature afforded by softness sometimes. Read this wonderful biography and judge for yourself. As Andrew McMillan says, who admired the published letters for getting us ‘closer’ to Gunn, with ‘this meticulously researched biography, we don’t so much move closer as move in with Gunn and shadow him through his life’. And why not? It may bore Sam Leith but it would not bore anyone for whom experimental queer lives matter and who recognise the necessary cost they bore in living them in the name of change for the better.

All my love

Steven xxx

[1] From: The Annihilation of Nothing (1958) Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/27820/the-annihilation-of-nothing

[2] Gunn to Mike Kitay cited in Michael Nott (2024:180) Thom Gunn: A Cool Queer Life London, Faber & Faber Limited.

[3] Michael Nott (2024:238) Thom Gunn: A Cool Queer Life London, Faber & Faber Limited.

[4] Andrew McMillan (2024: 35) ‘Lyric and Leather’ in Literary Review (Issue 532, August 2024), 35 – 36.

[5] Daniel Swain (2024) ‘A Masque of Difference and Likeness: On Michael Nott’s “Thom Gunn: A Cool Queer Life”’ in The Los Angeles Review of Books (June 18, 2024) Available at: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/a-masque-of-difference-and-likeness-on-michael-notts-thom-gunn/

[6] Ibid: 208

[7] Swain, op.cit.

[8] Sam Leith (2025: 49) ‘Smoking Gunn’ in The Guardian (Supplement) [Sat. 27th July 2024], 49.

[9] Andrew McMillan op.cit: 36

[10] Steve Donoghue (2024) Review: Thom Gunn: A Cool Queer Life by Michael Nott in Open Letters Review (online) [June 27, 2024] Available at: https://openlettersreview.com/posts/thom-gunn-a-cool-queer-life-by-michael-nott

[11] Information from: The Long War Against LGBT Foster/Adoptive Parenting | On the Science of Changing Sex (wordpress.com)

[12] Cited Nott, op.cit: 139

[13] Ibid: 183

[14] Gunn cited ibid: 84

[15] Gunn cited ibid: 321

[16] Ibid: 513

[17] https://livesteven.com/2024/08/11/in-michael-notts-2024-biography-of-the-poet-thom-gunn-the-man-closest-to-him-throughout-his-life-is-quoted-as-saying-of-thom-he-needed-people-to-think-he-was-happy-but-sometimes-when/

[18] Nott op.cit: 295

[19] Steve Donoghue (2024) Review: Thom Gunn: A Cool Queer Life by Michael Nott in Open Letters Review (online) [June 27, 2024] Available at: https://openlettersreview.com/posts/thom-gunn-a-cool-queer-life-by-michael-nott

[20] Colm Tóibín (2024: x) ‘Preface’ in Thom Gunn The Man with Night Sweats, London, Faber & Faber, vii – xi.

2 thoughts on “‘Stripped to indifference at the turns of time’ (1): Thom Gunn, life, love, and even poetry, in queer history. This blog reflects on Michael Nott (2024) ‘Thom Gunn: A Cool Queer Life’. ”